After the Fire: NewsHour Coverage of Civil Unrest in America, 1991-2021

L.A. Riots

On March 3, 1991, in the early morning, Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) officers engaged in a high-speed chase with motorist Rodney King on an L.A. freeway and on surface streets through a San Fernando Valley neighborhood. When King eventually stopped, police ordered him and his companions out of the car, and King, suspected of having a weapon (he did not have one), was told to get down on the ground. Officers Stacey Koon, Laurence Powell, Timothy Wind, and Theodore Briseno, who claimed King was resisting arrest, proceeded to tase and violently beat him. In 81 seconds, they struck him 56 times, causing severe injuries including “nine skull fractures, a broken cheek bone, a shattered eye socket, and a broken leg.”2 George Holliday, who lived near the intersection where the beating occurred, recorded the incident of police brutality with his camcorder from his apartment. The video soon saturated the news media and became the focal point not only of conversations about racism and police brutality, but also functioned as a key piece of evidence in the subsequent trial against the four officers. While the prosecution argued that the tape provided evidence of excessive force, the defense, by showing the tape in slow motion and isolating each of the officers' actions, argued that Rodney King had been “in control of the situation.” This manipulation of the tape ultimately led the majority white jury to acquit Officers Koon, Wind, Briseno, and Powell of assault charges.3 The jury failed to reach a verdict on excessive force charges against Powell, who delivered the most blows to King and struck him in the face, while acquitting the other three officers of those charges.

After the verdict was announced on April 29, 1992, demonstrators gathered outside the Los Angeles County Courthouse to protest the jury’s decision. The “not guilty” verdict sparked outrage, coming as it did on top of previous incidents of police brutality and consistent devaluing of Black lives in the criminal justice system. The previous year, a Korean grocery store owner in Los Angeles, convicted of voluntary manslaughter after shooting Latasha Harlins, a Black teenager, had received only a sentence of probation. Like the Rodney King beating, Harlins’ killing was caught on tape.4

Within the Black community, there were demands for justice as well as widespread criticism of the trial’s execution, mostly pertaining to the relocation of the trial from Los Angeles County to Simi Valley, a majority white suburb 30 miles outside of Los Angeles.5 Leaders, like L.A. Mayor Tom Bradley and Representative Maxine Waters (D-California), expressed their profound anger at the verdict, condemning the blatant racism and lack of police accountability they perceived in evidence in this case.

Bradley: “I was shocked. I was stunned. I was –I had my breath taken away by the verdict that was announced this afternoon. We have come tonight to say we have had enough. We encourage you to express your outrage and your anger verbally. We don’t intend that any of you should go out and burn down any buildings or break any windows.”

Waters: “I am angry. I am outraged. I think there has been a miscarriage of justice and I suppose I should have known once there was a change of venue and that trial was moved to basically an all-white community, but I suppose I was foolish enough to believe that given the very graphic depiction of the beating of Rodney King captured on video that there would be an undeniable assignment of responsibility to those who had, in fact, beat him. Unfortunately, we saw a verdict that I have no problems in identifying as a racist verdict.”

Their sentiments were shared by many L.A. locals, and later that evening, the unrest escalated. Motorists were pulled from their vehicles and beaten, windows were smashed, shops were looted, and buildings burned. Governor Pete Wilson declared a state of emergency and ordered the National Guard into Los Angeles. The unrest continued for five days, ending on May 3. In total, 63 people died, more than 2,000 were injured, and 12,000 arrested. The property damage was estimated to be over one billion dollars, and tens of thousands of people lost their jobs.6

The L.A. Riots, judged by contemporary historians as “the worst civil disorders since the 1960s,” drew considerable attention from American news media.7 As NewsHour correspondent Jeffrey Kaye maintained, “From the moment on April 29th, when the jury’s decision in the King beating case was broadcast live, television was relentless in its coverage of the aftermath.” This relentlessness led to a number of ethical mishaps and offenses, and in the aftermath of the coverage, national and local news stations received considerable criticism from both scholars and activists for their handling and representation of the riots. In an analysis of the coverage, John Thornton Caldwell, professor of media studies at UCLA, described the “othering” processes employed by news organizations, which referred to the men and women involved as “thugs” and “hoodlums” with nothing better to do then to loot and smash windows. These kinds of statements stigmatized the people involved in the unrest by depicting them as “marginal and alien." Caldwell also stated, “With this kind of officially concerned verbal discourse on television, fifty years of Los Angeles social, political, and economic history – indeed the very notion of causality or context in any form – simply vanished.”8 Caldwell criticized the limited representation news outlets afforded to the participants in L.A.’s unrest and the use of helicopter cameras to record the events down on the ground. As with the use of terms like “thug” and “hoodlum,” Caldwell held that these media tactics dehumanized the participants in the L.A. Riots by characterizing them as the “bad guys” without offering them the opportunity to explain their perspective. He also contended that this fueled an “us versus them” narrative presented by the local and national news media while also leading to an inaccurate framing of this event.9 Overwhelmingly, he noted, the unrest was portrayed as a black-white issue, almost entirely leaving out the involvement of other ethnic groups –specifically Asian Americans and Latinos – in the riots.

As a part of its extensive coverage of the L.A. Riots and its aftermath, on May 21, 1992, the NewsHour ran a story on the news media’s portrayal of the riots. The segment, “Covering the Coverage,” addressed many of the concerns raised by critics of the television news outlets. Jeffrey Kaye, the NewsHour’s Los Angeles correspondent, spoke with Murray Fromson, journalism professor at the University of Southern California, who criticized the lack of analysis in television coverage of the unfolding events. “Have somebody who knows something about the community, somebody who’s a resident of the community, talk about what’s going on, where are they, who are the people, are they the targets, and what do they have to say about all this,” Fromson advised. These questions, he stated, were neither asked nor answered. Instead, reporters mostly offered their outsider’s perspectives, presenting their narration of the events as the full story. According to Fromson and Kaye, there were minimal efforts to contextualize and understand L.A.’s unrest. Echoing these criticisms, Rubén Martínez, reporter for the L.A. Weekly, and Brenda Paik Sunoo, news editor at the Korean Times, in interviews with Kaye, discussed the lack of representation in the media of L.A.’s Latino and Korean communities during and after the riots. Martínez stressed L.A.’s ethnic and cultural diversity and took issues with television’s oversimplification of the riots: “South Los Angeles is 50 percent Latino and 50 percent African American, yet the TV coverage did not see the 50 percent that was Latino…. We are a city that is extremely complicated. What we were seeing on TV was very simplistic, was a Black and white or a Black and Korean story. It was not that at all.” Sunoo, in criticizing the circulated images of Korean merchants shooting guns, challenged the news media’s portrayal of Koreans during the riots: “They were firing back at people that were shooting at them. The reason Koreans had to defend themselves is that, you know, for two days there was just absolute lawlessness, and their stores and lives were in jeopardy, so they had no choice but to defend themselves. And that’s basically what happened. But the image was very skewed to just show that shooting, not being shot at.” Both journalists maintained that by excluding the experiences of the Latino and Korean communities, the television coverage of the riots did not communicate the full story of L.A.’s unrest.

|

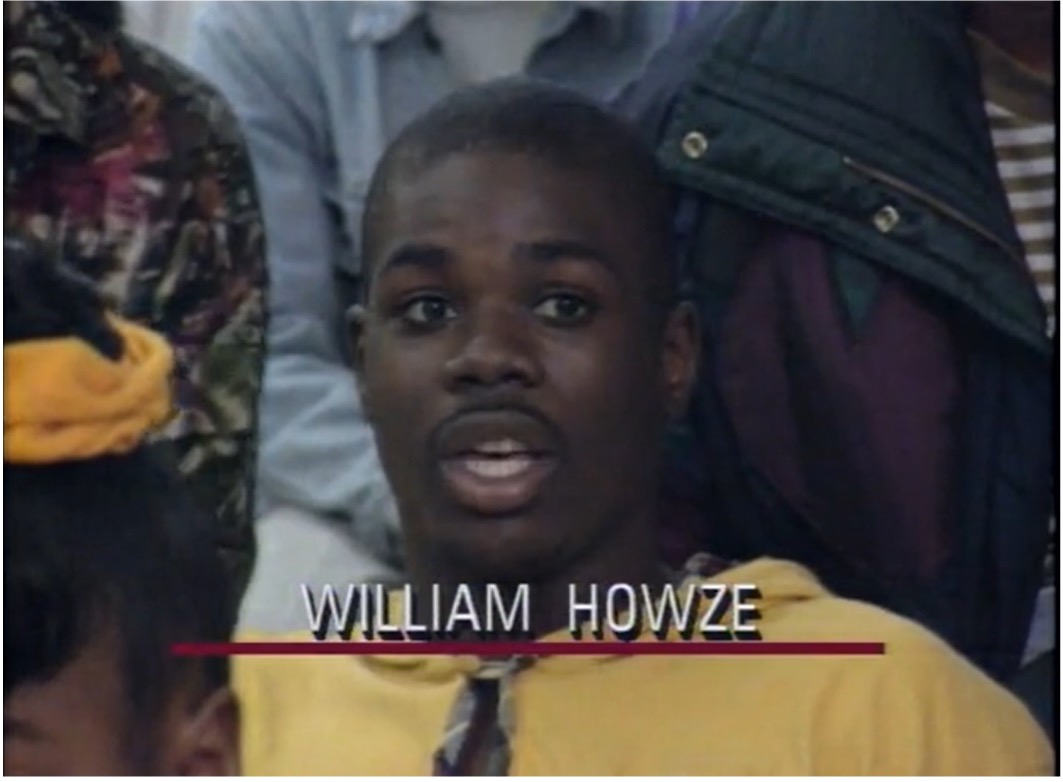

The NewsHour, in its own coverage of the L.A. Riots, strove to address these issues of representation and context. L.A. correspondent Jeffrey Kaye interviewed demonstrators in Los Angeles during the first days of unrest, offering them a platform to share their perspectives and explain their responses to the verdict. One demonstrator, a Black man out on the street encouraging cars to honk their horns, responded, “We’re trying to make noise, okay. Noise brought you here. Noise brings the media here. Noise brings attention here. Upon making the noise, hopefully we can get some response.” In the aftermath, the NewsHour continued to cover the Black community’s reaction to the verdict and the riots as well as their explanations for the unrest. Jeffrey Kaye interviewed L.A. residents, community activists, and high schoolers. Back in the studio, representatives from L.A.’s Black community, such as John Mack, were invited to participate in NewsHour conversations. Making the effort to avoid the black-and-white frame for which other news outlets had been criticized, the NewsHour also brought some attention to how the riots impacted other minority communities in L.A. The “Roots of Violence” segment highlighted the violence and destruction that occurred in Latino neighborhoods and examined the police reaction in these communities. In an interview with Kaye, Madeline Janis from the Central American Refugee Center argued that the LAPD used the riots as an excuse to arrest immigrants and turn them over to the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). Except for Paik Sunoo, who discussed the impact of the news coverage on Korean Americans, the NewsHour did not interview or invite representatives of L.A.’s Korean community to reflect on their experiences during the unrest. However, some news summaries did briefly describe the devasting impact of the riots on Korean-owned businesses.

|

As part of its 1992 coverage of the riots, KCET submitted a compilation of NewsHour segments for the George Foster Peabody Award. The following KCET programs also were submitted for the 1992 Peabody Award for their coverage of the L.A. Riots: “A Chance to Talk”; “Beyond the Rage”; “Return to King Blvd”; “Special Edition: After the Verdict”; “Rage & Responsibility”; and "Special Edition: Exit King Blvd."

Coverage of the L.A. Riots continued for more than a year as the NewsHour sought to identify and explore the causes of the rioting while determining its lasting impact not only on the city and its residents, but on America as a whole. As chronicled by the NewsHour, the debates over the riot’s roots during an election year were particularly tense as Republicans and Democrats were eager to play the blame game. Both parties hoped to assign blame for the riots to their opponent’s politics, policies, or ideologies. Democratic Party presidential candidate Bill Clinton attributed the cause of the riots to twelve years of Republican administrations and funding cuts for social services. A spokesperson for the George H. W. Bush administration, on the other hand, blamed the Democratic Party’s welfare policies of the 1960s and 1970s. Attorney General William Barr attacked LBJ’s Great Society programs and implied that a consequent rise in the number of illegitimate children in the inner cities had made “instilling values and educating children [difficult] when they had their home life so disrupted.” Vice President Dan Quayle suggested that the popular television sitcom Murphy Brown, by “mocking the importance of fathers by bearing a child alone and calling it just another lifestyle choice,” was partially at fault.

The NewsHour moderated many conversations about the causes of the L.A. Riots, bringing on many kinds of guests, including authors, academics, lawyers, politicians, police officers, and church leaders. In these talks, the riots frequently served as a catalyst to explore broad topics like race, economics, and politics. The guests debated how matters such as family values, policing, urban development, and economic inequality fueled the tensions leading up to the L.A. Riots. Outside the studio, NewsHour correspondents continued these kinds of talks hoping to gain further insight into the impact of this event both in L.A. and throughout the country. In addition to interviews in the immediate aftermath of the violence, Jeffrey Kaye spoke with L.A. locals on the one-year anniversary of the riots to ask how their lives had changed and whether any progress had been made in the city of Los Angeles. Five years later, Kaye reflected with Urban Policy Professor J. Eugene Grigsby and Dr. William Faulkner on what had and what hadn’t changed for the city’s residents and economy. Looking at the impact outside of L.A., Charlayne Hunter-Gault interviewed voters in West Virginia, asking Kelly Staup, John Taylor and Tracy Self, to discuss how the L.A. Riots would be affecting their votes come November. She also had a conversation with recent college graduates in South Carolina about how this unrest had changed their perspective on race in America and how they believed it would impact their futures.

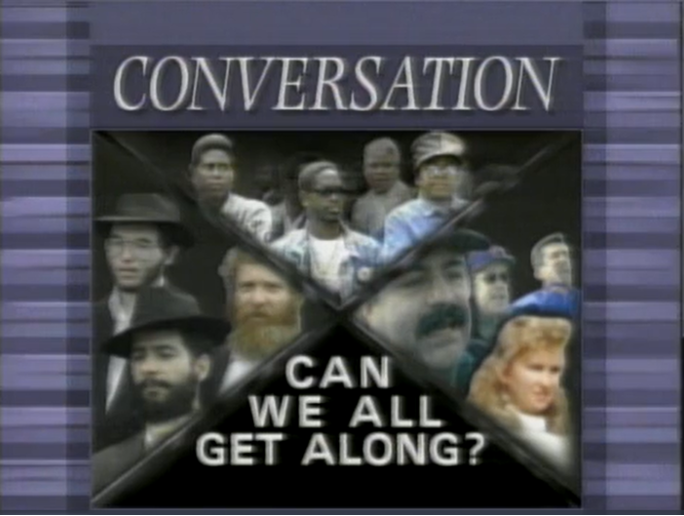

Starting in June of 1992, NewsHour correspondent Charlayne Hunter-Gault introduced the series “Can We All Get Along” to examine the state of race relations in America in the 1990s. She interviewed politicians, such as Housing and Urban Development Secretary Jack Kemp and former president Jimmy Carter, as well as artists, such as playwright and actress Anna Deavere Smith and editorial cartoonist Doug Marlette, along with a number of academics and professionals, including Evelyn Hu-DeHart and Joseph Boyce. In each interview, Hunter-Gault asked “Can we all get along?” echoing Rodney King’s call for peace following the verdict, and each guest offered their own unique take on this question of racial tension in America.

Anna Deavere Smith: I think it's going to be a long battle. I don't know if we can or not. I hope we can. But I don't know if we can. I don't know if it's all up to individuals. It's like again back to this whole melting pot analogy. Your interview with [sociologist] Christopher Jencks wants me to make a whole, makes me want to make a piece about that. Does the melting pot exist? Did it exist? Because he said to you also that what whites think is, well, I'm quoting him badly I'm sure, but what whites think is, why don't you act like us, everybody else did, the Italians did, the Poles did, and so forth, why don't you act like us, why don't you participate in other words, and you said something like, well, why not, and he said, because the whites won't let them. It's kind of crazy. You know what I'm saying? How can you really negotiate that? And I think many of us in our whole lives, if we're Black, have tried to negotiate that double message, try to figure it out. I mean, come here, take this job. We really are looking for women of color here. We've got to do something about this. And then when you get there, whoa, when you're in the flesh and you're not an abstract, then you have to do all this work to stay there if you want to stay there.

Evelyn Hu-DeHart: Well, you know, I don't think what really divides America is this pluralism that seems to some people to be at the root of our problem. What is different about America is that even as this country's always been ethnically, racially, culturally diverse, we have not conceded power to these people. We have constructed this country as a white country. I'm a professor at a major public institution. Out of a thousand or so full-time faculty members in that major public institution, there are less than 10 percent faculty of color, fewer than 10 percent are faculty of color, and of that, I am the only one I believe who is a full professor, woman and person of color, one out of a thousand. Now is that progress? I don't think anyone would say that's progress.

President Jimmy Carter: I think so. Most of my work since I left the White House has been in international affairs, in negotiating peace and dealing with human rights and planting corn in Africa and immunizing children, things of that kind. We've now turned our attention at the Carter Center to try and prove in Atlanta -- we call it just simply the Atlanta Project -- that these problems are not insoluble, that we can get along, that we can act as equals, that we can share the future, that we can acknowledge the plight of one another, that we can accept the difference in racial characteristics or heritage or the way of life or even family structures, and I think that this -- it will be a successful project. If it does turn out to be successful to a major degree, which I don't intend to fail, then we want to share it with other communities.

In a recent conversation, Charlayne Hunter-Gault explained that the goal of the series was to bring in people of all different backgrounds to offer solutions to these kinds of issues that the viewers could then integrate into their lives. She hoped to “open the door to greater information” for viewers at home, allowing them to think more critically about race and prejudice in America.10 There were eleven installments of “Can We All Get Along?” in 1992, and the NewsHour continued Hunter-Gault’s discussion of race in America in the series “Race Matters,” which first launched in 1995 and is still a reoccurring segment today.

|

No other event of civil unrest in the U.S. received as much NewsHour coverage as the L.A. Riots did. For some events, the NewsHour only covered the unrest or its immediate aftermath in one or two segments, for example, the 2001 Cincinnati Riots, 2007 MacArthur Park Rallies, and the 2017 St. Louis Protests. The NewsHour covered the 1991 Crown Heights riots in only one segment two years later to investigate its effect on the 1993 New York Mayoral race. For events that received more coverage, like the 2011 Occupy Movements, the 2014 Ferguson Protests, the 2015 Baltimore Protests, or the 2017 Charlottesville Rally and Counter-Protests, the NewsHour examined the causes and effects of the unrest by getting on-the-ground perspectives and having in-studio conversations as they did with the L.A. Riots, but it was not done to the same extent.