The HIV/AIDS Epidemic and Public Broadcasting

1981-1985: Early Reporting on the "Gay Disease"

The following section examines AIDS-related programs from 1981-1985, when AIDS was generally understood to be a "gay disease" and not one that would affect the general population. The programs include the first episode of The MacNeil/Lehrer Report dedicated to the epidemic, in addition to several other episodes from the Report; a program about gay and lesbian rights in 1983; an early documentary about the AIDS epidemic; and several others.

This section contains the least number of programs. Media coverage of the epidemic in the early 1980s was sparse, and without any significant governmental response to AIDS, this period has been called by scholars "one of official neglect."17 By looking closely at these programs, we can see how public broadcasting programs covered the epidemic at a time when little coverage existed.

In 1981, the CDC reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) that five gay men in Los Angeles had been treated for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in recent months. This kind of pneumonia is rare and usually contracted by people with suppressed immune systems. An editorial note read, "The occurrence of pneumocystis in these 5 previously healthy individuals without a clinically apparent underlying immunodeficiency is unusual. The fact that these patients were all homosexuals suggests an association between some aspect of a homosexual lifestyle or disease acquired through sexual contact and Pneumocystis in this population."18 This was the first AIDS-related MMWR and the beginning of scientists' interest in what eventually became known as AIDS. Years before this report, unusual numbers of healthy gay men and people experiencing homelessness were dying suddenly of pneumonia, sometimes colloquially known as "junkie pneumonia."19 We now know that HIV/AIDS existed decades before this initial report, but had gone undetected by scientists.

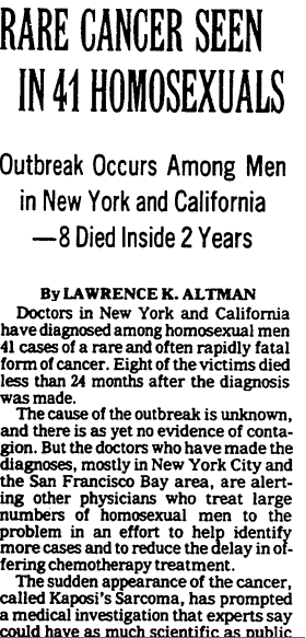

Later that year, following another MMWR, the New York Times reported that Kaposi's sarcoma, a rare cancer, was discovered in an alarmingly high number of young gay men.20 This article began mainstream coverage of the epidemic, which had existed for decades without official scientific diagnosis. The CDC coined the term Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, or AIDS in 1982. The report connected the outbreaks of Pneumocystis pneumonia and Kaposi's sarcoma to AIDS and stated that approximately 75% of reported AIDS cases were among homosexual and bisexual men. The report also identified particular "risk factors" that represented the majority of AIDS cases. Groups that became colloquially known as the "Four H Club" – "Homosexuals, heroin users, hemophiliacs, and Haitians"21 – experienced immense prejudice and violence because of their association with "AIDS risk" from the beginning.

Rep. Henry Waxman called the first congressional meeting in April 1982 on what was called Gay-Related Immune Deficiency (GRID), or the "gay cancer," as a Reagan administration budget proposal under consideration threatened to cut NIH grant funding and effectively cut CDC funding. At the hearing, which only one reporter attended, Waxman argued that the government was slow to respond because GRID primarily affected gay men and stated, "We can't talk about the gay cancer. There is a cancer which seems predominantly to affect gay men, but it is a cancer and a public health concern for all Americans."22 Bobbi Campbell, a gay man who worked as a nurse and journalist, attested to the cost of having opportunistic infections; he had accrued over $10,000 in medical charges. Thomas Nylund, director of medical services for the Gay and Lesbian Community Services center, testified that the epidemic was estimated to cost the U.S. $70 billion. While a central message of the hearing was a need for funding and effective public policy, reporting on the hearing did not address these concerns. Rather, a Los Angeles Times article written about the hearing focused on the fact that heterosexuals were beginning to be affected by the "gay disease."23

|

Early reporting on AIDS closely associated the disease with gay men. While gay men were disproportionately affected by the disease, this kind of reporting, in addition to the CDC's identification of male homosexuality as a major "risk factor," contributed to the general impression that only gay men should be concerned about contracting the disease and that AIDS was not a national concern. In addition, such discourse fed into homophobic stereotypes that associated gay men with recklessness and with suffering. Scholar Paula A. Treichler writes, "The 'promiscuous' gay male body… made clear that, even if AIDS turned out to be a sexually transmitted disease, it would not be a commonplace one."24 The portrayal of AIDS as a "gay disease" also interfered with proper diagnoses in women and children. For example, CDC surveillance definitions of AIDS in the early 1980s excluded gynecologic symptoms, and women were excluded from research and drug trials.25

Public television's nightly national news analysis program, The MacNeil/Lehrer Report, first covered AIDS on August 26, 1982, in an episode titled "AIDS: The Mysterious Disease." As Jim Lehrer reported, "It's considered bizarre because, unlike other diseases, it suppresses a person's natural immunity against various infections and certain types of cancer." Correspondent Charlayne Hunter-Gault interviewed Dr. Bijan Safai, chief of dermatology at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, who had been treating patients with AIDS for two years. Dr. Safai explained what had been identified as the common signs of AIDS, including Kaposi's sarcoma, infection, and "wasting syndrome." Most importantly, he made clear that scientists believed "the agent" that caused AIDS was transmitted through sexual contact and blood. This fact would be strongly supported by a CDC report in January 1983.26 Later public broadcasting programs frequently repeated this information to viewers, who more likely than not believed that HIV could be spread through casual contact. In September 1985, years after the 1983 CDC statement, the New York Times reported that "half of the American people believe AIDS can be transmitted through casual contact despite what Federal scientists say is overwhelming evidence to the contrary."27

Later in the Report, Jim Lehrer interviewed Dr. James Curran, leader of the CDC's AIDS task force, who asserted that the spread was epidemic-level. Dr. Curran stated that AIDS had been found in gay communities, among people who use IV drugs in specific cities, and hemophiliacs. By the end of the year, 771 cases of AIDS had been reported in the U.S., and 618 people had died from AIDS-related complications. The CDC established the National AIDS Hotline in February 1983.28

|

In September 1983, KTCA in Minnesota aired an episode of People and Causes featuring representatives from the Minnesota Civil Liberties Union (MCLU) and Minnesota Gay and Lesbian Legal Assistance. They discussed laws criminalizing sodomy that were used selectively to arrest gay men. Linda Ojala, Attorney and Associate Executive Director of MCLU, cited a raid of the Locker Room Bath House on December 1, 1979, as an example. This broadcast covered other legal challenges faced by gay people in the early 1980s, including legal employment and housing discrimination, both of which had become compounded by the fear of people with AIDS.29 Ojala suggested, "The danger is that [AIDS] will be used as an excuse for discrimination" and referenced language used by Jerry Falwell, founder of the conservative Christian organization The Moral Majority, that AIDS was the "wrath of God" exercised on gay men for sexual immorality.30

The next month, KCTS in Seattle broadcast the documentary "Diagnosis: AIDS," a close look at medical research, activist protests, and homophobic rhetoric inflamed by the epidemic. Early in the program, common misconceptions about AIDS were identified and refuted. These misconceptions, determined by a Gallup survey, included the idea that AIDS spreads in public pools and restrooms, at restaurants, and in the workplace.

|

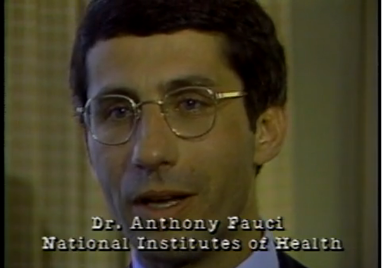

The program featured responses to the epidemic by prominent figures in the government and the medical field. These figures included Dr. James Curran of the CDC, Dr. Anthony Fauci from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Dr. Richard Crowsey from NIH, Dr. Hunter Handsfield, director of Seattle's STD clinic; and Margaret Heckler, Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), as they convened for the 5th International Society for Sexually Transmitted Diseases Research Conference in Seattle. AIDS activist Bobbi Campbell, a person with AIDS (PWA), was also featured, along with Rev. Jerry Falwell, leader of The Moral Majority and outspoken conservative activist, who stated that AIDS, like other STDs, was "a result of violating the laws of decency and of nature."

The question of how to prevent the spread of disease was central to the program. Falwell argued that bath houses, private businesses where sexual activity sometimes occurred, should be closed. In response to criticism of this proposal, Falwell replied, "A shutdown of the bath houses, where the most vulgar, dirty, and bloody, and filthy things happen, is not an anti-gay proposal, but, we think, rather, a pro-gay proposal to protect them from themselves until there is medical evidence that there is no danger in what they’re doing." Dr. Crowsey stated in the program that "gay men should not partake in [sexual] activity." In contrast, Bobbi Campbell suggested that a more effective public health response would encourage the use of condoms to prevent the spread of disease.

Campbell also discussed examples of prejudice that people with AIDS faced, including a man whose roommates burned his belongings and insisted he move out of their home. Dr. Fauci clarified that AIDS cannot be contracted through casual contact like common respiratory viruses, and the program's narrator stated that no healthcare workers had contracted the disease from patients, as many had feared.

|

The KTCA and KCTS programs were rare for this period of the epidemic. After MacNeil/Lehrer expanded in fall 1983 to become the nation's first hour-long nightly news program, the series covered AIDS as breaking news about the epidemic emerged. In September 1983, The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour reported on a nun who had died in 1981 and who, doctors believed, had contracted HIV in Haiti in the 1970s. The program also included a segment, produced by KCTA in Minneapolis that followed Bill Runyon, who had experienced social ostracization and unemployment following his AIDS diagnosis. In another NewsHour segment, Robert MacNeil reported that scientists had located a leukemia virus they suspected caused AIDS.

A tonal shift occurred in broadcast coverage in July 1985, when the news broke that the famous actor Rock Hudson was diagnosed with AIDS. The NewsHour closely followed the event, offering daily updates on Hudson's status. Jim Lehrer even mentioned the impending availability of HPA-23, a then-experimental antiretroviral drug used to treat HIV, which was prescribed for Hudson.31 One 1985 NewsHour segment profiled John Coffee, who also was treated with HPA-23. Both Hudson and Coffee travelled to France for treatment with the drug, which was one of several AIDS drugs that had not been approved by the FDA. In fact, by this time, the FDA had yet to approve any drugs for AIDS treatment. In October, the Senate voted to increase funding of AIDS research and treatment programs by $221 million.32 An article from Science suggested that "at least part of the credit for this new push [to increase spending and research for HIV/AIDS treatments] should go to actor Rock Hudson, whose much publicized trip to Paris for experimental therapy focused public and political attention on the desperate plight of those diagnosed with AIDS."33

Signaling that AIDS was becoming a national issue, Hudson's diagnosis led to more reporting on AIDS and contradicted the general public's belief that only certain populations were vulnerable to the disease.34 Although Hudson was a gay man, he had not publicly disclosed his sexuality. A column in the gay magazine Outweek read, "Not until Rock Hudson was afflicted and scientists began to warn about the possibility of a spread into the 'general population' did this dire national emergency become a big story."35 As the public began to believe that AIDS was not only a problem for gay men and people who used IV drugs, there was a surge in news coverage.36 In addition to being a beloved celebrity, Hudson was also a close friend of President Ronald Reagan, who still had not acknowledged the epidemic in public. Hudson's diagnosis and death prompted the president to consult the White House physician and to ask Surgeon General C. Everett Koop to write a report on AIDS the next year.37

|

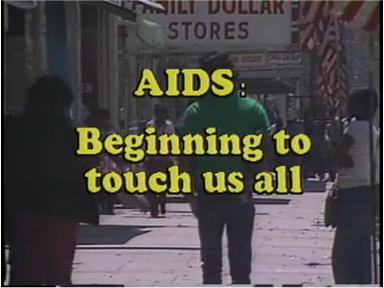

With increased concern about AIDS spreading to the general population came further misunderstandings about how the virus that causes AIDS spreads. In August 1985, the South Carolina Educational Television Network (SCETV) aired a Carolina Journal segment titled "AIDS: Beginning to Touch Us All." The program featured an interview with Robert Jackson, Commissioner of the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control. In response to growing panic about children with AIDS in schools and adults with AIDS in workplaces, Jackson insisted there was no risk of transmission in those circumstances.

Notably, Jackson was asked his opinion on accusations from the gay community that researchers and the government had failed people with AIDS in the early years of the epidemic. He noted perceptions that the Reagan administration, "because of its very high association with very fundamentalist religious principles and its conservatism, for a long time wanted to ignore the fact that AIDS was out there. And that there were a number of people who were supportive of that administration who felt, perhaps, the way many fundamentalists do that AIDS may in fact be a ravage that is caused by immoral behavior and what have you. I think that we have gone past that now."

At the end of 1985, 15,527 cases of AIDS had been reported, and there were 12,529 recorded deaths related to AIDS. President Reagan had yet to publicly address the epidemic, federal funding for HIV/AIDS research and prevention efforts were virtually non-existent, and news coverage was finally picking up.38