The HIV/AIDS Epidemic and Public Broadcasting

Overview

The HIV/AIDS epidemic radically changed public health policy, social attitudes toward gay men, and the course of LGBTQ+ history in the United States. This collection includes public broadcasting archival materials that demonstrate attitudes toward and responses to the epidemic. A resource for anyone interested in understanding how public broadcasting has covered HIV/AIDS, this exhibit places featured programs within a contextualized history of the course of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the United States and the U.S. response to AIDS in Africa following the decline of new cases in the U.S.

The exhibit was devised and curated by Elizabeth Dinneny, a 2022 Library of Congress Junior Fellow and English PhD candidate at the University of Maryland. Sonia Prasad, an intern in the Library of Congress Archives, History, and Heritage Advanced Internship (AHHA) program and graduate of Williams College, curated the section on coverage of AIDS in Africa.

This project would not have been possible without the support of Mariah Marsden, Alan Gevinson, and Casey Davis. Thank you to those who helped make these programs available online: Robert Chehoski, Tina DiFeliciantonio, Peter Friedman, Amber Hollibaugh, Vivian Kleiman, Asad Muhammad, Richard Rasch, Gini Reticker, Jane Wagner, and Hannah Weber. Thanks also to the exhibit’s anonymous reviewer.

A special thank you to Fabio Toblini, who granted the AAPB permission to add activist and filmmaker Robert Hilferty’s historic, award-winning documentary Stop the Church to the Online Reading Room.

Introduction

Homophobia was commonplace before the HIV/AIDS epidemic began. Although LGBTQ activism had existed in the U.S. since the early twentieth century and increased dramatically during the gay liberation movement, which began during the Stonewall Riots in 1969, LGBTQ people still had few civil rights protections. Before the start of the epidemic, twenty-five states and the District of Columbia had laws that criminalized sodomy, and in 1986, the Supreme Court affirmed the constitutionality of a sodomy law in Georgia.1 Sodomy laws were almost exclusively applied in legal cases against gay men, who could be arrested for consensual acts in their own homes. Employment discrimination against gay people was legal.2

For the first several years of the epidemic, AIDS was not a concern for most Americans. Many believed AIDS was a "white gay male disease" contracted through promiscuous sex, and this belief contributed to social indifference—if not revulsion—toward HIV/AIDS, especially in the beginning. Susan Sontag wrote, "The sexual transmission of this illness, considered by most people a calamity one brings on oneself, is judged more harshly than other means—especially since AIDS is understood as a disease not only of sexual excess but of perversity."3 That the majority of AIDS patients in the early 1980s were gay men meant that many Americans did not consider AIDS to be a major health threat, federal and local governments did not respond adequately to what was a growing health crisis, and gay men continued to die at increasing rates and with no treatment options.

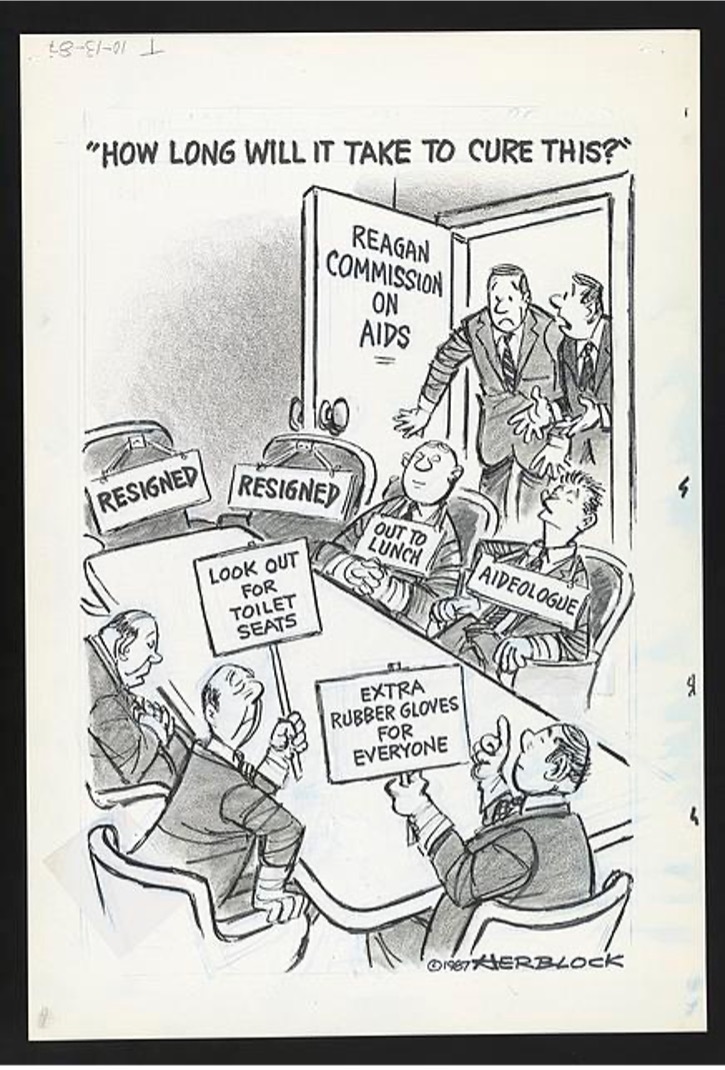

The Reagan administration's delayed response to the epidemic was strongly criticized for allowing the threat of HIV/AIDS to grow.4 In the early 1980s, the Reagan administration cut public health funding, and the administration was consistently reluctant to provide additional funding for AIDS research, despite requests from researchers and the gay community.5 In 1983, at a subcommittee hearing on AIDS, Dr. Marcus Conant, who treated patients with AIDS, stated that "the failure to respond to this epidemic now borders on national scandal."6 The president's proposed budget for fiscal year 1984 cut $300,000 from Centers for Disease Control (CDC) AIDS funding, and the federal government had not created any AIDS prevention campaigns.7 At a hearing, Stan Matek, past president of the American Public Health Association, said that the administration told health officials, "Don’t ask for any money. Make us look as good as you can with what you’ve got."8 After the death of his close friend, Rock Hudson, to AIDS, and after mounting pressure due to public concern about the spread of HIV, President Ronald Reagan finally publicly addressed the epidemic in 1985. By the end of 1985, over 12,000 people had died of AIDS in the U.S. President Reagan gave his first major speech on the epidemic in 1987. Throughout his presidency, Reagan opposed legal protections for people with AIDS.9

|

A lack of media coverage, in addition to misrepresentations of the epidemic and people with AIDS, contributed to national apathy toward HIV/AIDS. Journalist James Kinsella argues that "at least some of the blame for the ravages of AIDS in America must lie with members of the media who refused to believe that the deaths of gay men and drug addicts were worth reporting."10 As we will see especially in the first section of this exhibit, media coverage was indeed sparse in the early 1980s. When AIDS was colloquially known as a "gay plague," the epidemic was not a priority for the news media and most of its audience. Many spikes in coverage of the epidemic coincided with the fear that AIDS had become a threat to the "general population," rather than only to gay men.11

In the midst of prejudiced media coverage and a lack of federal guidance, public broadcasting stations and producers designed their own programs for educating the American people. This exhibit highlights national and local reporting, interviews, and documentaries broadcast on public television and radio that not only communicated life-saving information about HIV and AIDS, but also shed light on the struggles faced by AIDS patients and their communities of support. It also explores several controversies surrounding AIDS-related programming, including concerns with privacy, exploitation, and misrepresentation of people with AIDS.

While examining this wide collection of HIV/AIDS-related programming, we should encounter stories of people with AIDS with careful consideration of the contexts in which they were produced. The programs in this exhibit were created and aired in the midst of increasing instances of homophobic rhetoric and violence, governmental and social indifference toward the growing numbers of gay men dying of AIDS, and conservative activists like Jerry Falwell claiming that HIV/AIDS "is the wrath of God."12 Activists and scholars alike have criticized the portrayals of people with AIDS in the media. Scholar Paula A. Treichler writes of common stereotypical representations on television, such as "the emaciated gay man in a hospital bed; the 'innocent' transfusion victim surrounded by loving family; the Third World prostitute, in red." Treicher argues, "Counter-examples to these canonical AIDS victims were for many years systematically excluded from media reports, just as some people with AIDS were rejected by photographers because they did not look sick enough."13 Viewers of these programs should thus take a critical eye when trying to understand the history of public broadcasting's coverage of this period of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Some programs in this exhibit play into stereotypes, while others go beyond them. In other cases, activists use the media to communicate their own messages.

|

Readers should keep in mind that the HIV/AIDS epidemic is still ongoing. While featured materials mostly cover news, education, and research during the first 25 years of the epidemic, scientific developments still occur, and more than one million people across the country are living with HIV.14 Black, Latino, and LGBTQ+ people are acutely disproportionately affected by HIV, and access to treatment is not equal. Minority patients are significantly less likely to receive primary and emergency care for HIV/AIDS.15 For more information about the current state of the epidemic and tools for HIV prevention and treatment, you can visit the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) HIV Basics hub and this exhibit's epilogue.

How to Use This Exhibit

Scholar James Kinsella identifies three surges in AIDS coverage: (1) in 1983, when the general public feared that AIDS was spread through casual contact; (2) in 1985, when actor Rock Hudson announced his AIDS diagnosis and Americans believed that anyone could contract the virus; and (3) in 1987, when conversations about stopping the spread and testing caused another panic.16 These surges are reflected in public television and radio broadcasts, and in the organization of the exhibit. The first section, "1981-1985: Early Reporting on the 'Gay Disease,'" covers AIDS-related programs from the period before and immediately following Rock Hudson’s public announcement. The second section, "1986-1988: The AIDS Program Emerges," explores the sudden increase in public broadcasting's coverage of AIDS. It describes a controversy surrounding the 1986 Frontline documentary "AIDS: A National Inquiry" and analyzes two common types of programming from the period: legislative response coverage and local educational programming. The third section, "1989-1994: Beginning 'The Second Decade,'" provides a history of the AIDS Quarterly and other programs from this period. A fourth section, "1989-1991: Broadcasting ACT UP Direct Action," examines public broadcasting’s coverage of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), the most well-known AIDS activist group. A fifth section, "1995-1997: New HIV/AIDS Therapies and Strategies," details the development of highly active antiretroviral therapy, which became the standard for treatment and made living with HIV/AIDS manageable. Following these five sections on coverage of AIDS in the U.S., the exhibit continues with an additional section on coverage of AIDS in Africa and concludes with an epilogue. While the essays can be read out of order, the exhibit is organized chronologically to clearly map shifts in media coverage, medical achievements, and government responses. Listings of more than 200 additional nationally and locally broadcast public television and radio programs in the AAPB collection end the exhibit. In addition to the many programs discussed in the exhibit, you can find a more comprehensive list of AIDS-related programming available for online access in AAPB by clicking "View all exhibit records." The AAPB collection includes programming that has been contributed to AAPB by more than 1,000 stations and producers, but there are many more public television and radio programs still in need of preservation.