The HIV/AIDS Epidemic and Public Broadcasting

1989-1994: Into “the Second Decade”

Introduction

The male homosexual population was the first in this country to feel the effects of the disease. But in spite of what you may have heard, the number of heterosexual cases is growing.

– Understanding AIDS mailer, 198858

By “the second decade” of the epidemic, rates of HIV/AIDS among heterosexual people, especially women of color and IV drug users, were rising.59 Gay men were still at the highest risk, but were less often the focus of educational campaigns, news reports, and radio and television programs.60 AIDS activist Phill Wilson called the focus on women with AIDS at the Tenth International AIDS Conference in 1994 an “‘at-risk group of the year’ approach to epidemiology.”61 While the media often focused on women and heterosexuals with HIV/AIDS, gay and lesbian organizations provided education to their own communities. The national AIDS educational mailer “Understanding AIDS,” based on Surgeon General Koop’s report, did not include any clearly indicated images of gay men and only mentioned them explicitly in statements about how people of all sexualities were at risk. Rather than provide targeted, useful information about the epidemic to gay men, the government and news outlets often focused on how heterosexuals could get HIV.

The programs in this section reflect a more organized approach to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The basic facts of HIV/AIDS had been established, and the epidemic had been raging for a decade. In this section, readers will encounter The AIDS Quarterly and The Health Quarterly, two WGBH series that closely examined the epidemic for several years. The AIDS Quarterly covered a variety of topics relating to the epidemic, including racially segregated healthcare, women with AIDS, HIV/AIDS in prison, and the FDA drug approval process. Other radio and television broadcasts in this section include an interview with filmmaker Marlon Riggs, programs about women with AIDS, and one about protecting children from HIV/AIDS. This section also notes additional national coverage of the epidemic.

The AIDS Quarterly

The mission of this series is not to please one constituency or another, but to provide a forum for public debate on the [AIDS] issue. We’re producing the only ongoing national TV series about AIDS. Instances of controversy should in no way undercut the effectiveness of what we’ve done—and intend to do.

– The AIDS Quarterly project director Renata Simone62

In 1989, WGBH in Boston began to produce The AIDS Quarterly, a PBS series that reported on the epidemic and was “widely regarded as television’s most ambitious and comprehensive look at the AIDS epidemic,” Joseph Kahn reported in the Boston Globe.63 The magazine-style program included news updates, interviews and analysis, and documentaries. Of all the programs featured in this exhibit, AIDS Quarterly is particularly important, because it was intended to help fill an absence of consistent, quality coverage of the epidemic. Host Peter Jennings made this clear at the beginning of the very first broadcast, when he criticized a lack of media coverage despite rising case numbers, and when he admitted, “We in the media have not always been very helpful to you in understanding AIDS.” This self-awareness and dedication to regular reporting uniquely positioned The AIDS Quarterly in the AIDS media landscape. Until The AIDS Quarterly, the public broadcasting series that most consistently discussed AIDS was The MacNeil/Lehrer Report and NewsHour, which had been examining the epidemic since 1982.

|

The AIDS Quarterly inaugurated its magazine series with an overview of the epidemic. The first episode, which premiered on February 28, 1989, and is available for viewing at the Library of Congress and GBH, began by following the work of the Reagan administration’s Presidential Commission on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic, established in 1987 by Executive Order 12601. The commission was tasked with writing a report on the state of the epidemic and recommendations for governmental action. The program thus started its examination of the epidemic through the eyes of the presidential commission and particularly through the perspective of Admiral James D. Watkins, who became its chairman and who explained the commission’s work throughout the segment. The commission, which experienced turnover and controversies during its tenure, eventually made almost 600 recommendations, including treatment on demand for people who use IV drugs, anti-discrimination legislation, and an overhaul of the healthcare system, which they determined was not equipped to respond to the epidemic. President Reagan did not act on the commission’s recommendations before leaving office. In Watkins’ footsteps, the program featured interviews from people across the country who had experienced discrimination because of AIDS, activists who criticized the lack of research funding and stalled drug approval, and researchers working on HIV/AIDS. The final segment included an interview with Malcolm, a gay man dying of AIDS who reconnected with his Mormon family in the final months of his life.

The third installment of AIDS Quarterly received backlash for “mistakes” in two different segments: one for its representation of people of color who had AIDS and another for a comment made by Jennings that emboldened homophobia, critics charged. The segment titled “A Question of Civil Rights” scrutinized “racially segregated” healthcare available for people with HIV and AIDS in Chicago. The segment looked at Howard Brown Memorial Clinic, a “state-of-the-art facility” that treated mostly white gay men and was located in a white neighborhood, in comparison to healthcare facilities available to Black and Hispanic people with AIDS in Chicago, including an outreach center with “no treatment rooms, a tiny staff, armed only with condoms and bleach for cleaning needles.” The segment briefly followed Claude Rhodes, founder of a drug abuse treatment center in the 1960s, who joined the University of Illinois Chicago Community Outreach Intervention Project and “was known to take up to half an hour just to walk one block, stopping to talk and pass out bleach and condoms."64 Rhodes was shown walking down streets and into a “shooting gallery” to educate people on HIV/AIDS and provide condoms and bleach for disinfecting needles. Putting the comparison between healthcare facilities into context, the program informed viewers that Chicago returned $900,000 in funds from anti-AIDS grants that were not used in 1988.

Another segment told the story of a woman who had contracted HIV from her husband, who was having an affair with a man, and included interviews with experts on resources for and education about women with AIDS. Jennings mentioned that many early signs of HIV for women, such as yeast infections and cervical cancer, were not on the government’s official list of symptoms, which made diagnosing HIV/AIDS in women difficult, skewed case numbers, and disqualified women from taking experimental drugs and receiving disability benefits.

The episode received both negative and positive reactions. Larry Kessler, chairman of the AIDS Action Committee of Massachusetts, told the Boston Globe, “It pitted communities of color against gay whites. It showed blacks sharing needles in a slum, but no yuppies sharing needles in a loft. It suggested that at least some community-based clinics have gotten plenty of federal help, which is ludicrous. And it portrayed women with AIDS as innocent victims of uncaring men, which just about sent me through the ceiling."65 Kessler was responding to Jennings’ statement that bisexual men “don’t always tell the full story to the women they’re involved with.” Eric Rosenthal, political director of the Human Rights Campaign, a gay and lesbian lobbying group, said the segments gave the impression “that gay men are out there spreading the disease to women—and then stealing treatment money from blacks and Hispanics. That’s outrageous. It loads bullets in the gun for anyone who’s inclined toward homophobia in the first place."66 In another Boston Globe article, Richard Knox wrote that the episode was further evidence that The AIDS Quarterly was “simultaneously understated and urgent, broadly focused and yet powerfully human."67 In addition to the segments on racially segregated healthcare and a woman with AIDS, this episode also included an interview with Dr. Mervyn Silverman, president of amfAR, a segment on legal rights of gay couples when one died of AIDS, and footage of a funeral for an ordained minister, who died of AIDS complications. At the funeral service, AIDS was not mentioned at the request of the family, and the minister’s body was buried in a “far corner of the cemetery.”

The AIDS Quarterly provided the most comprehensive coverage by public broadcasting of HIV/AIDS and was the only regularly scheduled program dedicated to examining the epidemic. Like many AIDS programs, the Quarterly was not without controversy, but it made significant contributions to public knowledge. One public television staffer, when discussing how public television measures success, gave The AIDS Quarterly as an example of a program that was successful because it made an impact on people’s lives, saying that the series was “causing people to have an intimacy with their own families, and to talk about the disease that they have and they hadn’t even had the nerve to tell them about. I mean, that’s just, that’s a huge thing to have done, even to one person."68

The AIDS Quarterly ran from February 1989 to May 1990. Episodes of The AIDS Quarterly and its successor program, The Health Quarterly, which reported on issues of health in the U.S. and included an “AIDS Report” segment, are available to researchers on-site at the Library of Congress and GBH. Interviews conducted for The AIDS Quarterly and The Health Quarterly are available online in AAPB.

The AIDS Quarterly, “The Education of Admiral Watkins” (WGBH, Boston, February 28, 1989)

Provides an overview of the epidemic and interview with Admiral Watkins, chairman of President Reagan’s commission on AIDS.

The AIDS Quarterly, “Stopping AIDS: Stopping Drugs; The Art of Medicine” (WGBH, Boston, 1989)

Focuses on the medical aspects of the epidemic. Included are segments on AIDS research and its implications for the science of psychoneuroimmunology (PNI): a profile of two doctors--one in Massachusetts, the other in Iowa--and how AIDS has affected their practice of medicine, and a look at how billions of dollars of federal research is spent and who gets it.

The AIDS Quarterly, “A Question of Civil Rights; AIDS and the Second Sex” (WGBH, Boston, September 27, 1989)

Explores how racially segregated healthcare in Chicago affects Black and Hispanic people’s access to HIV/AIDS information, prevention, and care. Also follows one woman living with AIDS.

The AIDS Quarterly, “Christmas at Starcross” (WGBH, Boston, December 19, 1989)

This special edition of The AIDS Quarterly follows the care of children with AIDS at Starcross Christmas Tree Farm in Northern California.

The AIDS Quarterly, “The Trial of Compound Q; Money and Morals” (WGBH, Boston, January 31, 1990)

Examines the controversy surrounding the underground trials of Compound Q by Project Inform in San Francisco, in addition to the use of government funds for HIV/AIDS research and treatment. You can read more about Compound Q elsewhere in this exhibit.

The AIDS Quarterly, “Crisis in Texas; Prisoners of AIDS” (WGBH, Boston, May 23, 1990)

Analyzes the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the state of Texas and the spread of HIV inside prisons.

The AIDS Quarterly, “The Crisis in Poland; To Live with AIDS” (WGBH, Boston, November 26, 1990)

Takes a global look at the epidemic with a trip to Poland where the epidemic is causing a crisis for the health care system. Second segment is a monologue by Edmund White, an influential American gay writer. White tested HIV positive in 1985 and speaks about what it is like living with a disease for which there is no cure.

The Health Quarterly, 101 (WGBH, Boston, June 12, 1991)

Includes three segments: "My Job, My Health," "An Answer From Government," and "The AIDS Report: Decade of the Virus.”

The Health Quarterly, 102 (WGBH, Boston, September 23, 1991)

The Health Quarterly, 103 (WGBH, Boston, December 1991)

Includes three segments: "Return to the Delta," "A Better Way to Help," and "The AIDS Report: Gloria."

The Health Quarterly, 104 (WGBH, Boston, March 1992)

Includes three segments: "The Politics 1965-1992," "Reform Within Reach," and "The AIDS Report: To Keep Kids Safe."

The Health Quarterly, 201 (WGBH, Boston, June 1992)

Includes three segments: "Is Your Vote Good for Your Health?" "Children of DES," and "The AIDS Report: Dating in the Age of AIDS."

The Health Quarterly, 202 (WGBH, Boston, September 1992)

Includes two segments: "A Voter's Guide to Health Care" and "The AIDS Report: Advice to the Next President."

The Health Quarterly, 203 (WGBH, Boston, December 1992)

Includes two segments: "Doctors and Dollars," "The Health Update: Promises & Reality," and "The AIDS Report: A Hidden Risk."

The Health Quarterly, 301 (WGBH, Boston, March 1993)

Includes two segments: "Focus Documentary on TB" and "The Future of Reform: A Debate."

The Health Quarterly, 302 (WGBH, Boston, June 1993)

Includes two segments: "Focus Documentary on Clinton's Health Care Bill" and "The Family Doctor."

Selected Additional Programming

“Protect Yourself: Teaching Your Children About AIDS,” WTTW Journal (WTTW, Chicago, April 2, 1991)

“Protect Yourself” aimed to explore the issue of sex education for children through a live Q&A, educational segments, and three discussion panels. The content of sex education in schools was a highly debated topic, and this program included a variety of opinions and recommendations popular at the time, including abstinence-only education and safe sex education.

Express, “Sweating It Out / All About Cleve” (KQED, San Francisco, CA, 1989)

This episode of the KQED series Express includes a segment on Cleve Jones, gay rights activist and founder of the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt. The program covered Jones’s involvement in politics, activism, his HIV diagnosis, and the NAMES Project. The NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt requested submissions of quilt panels made in honor of people who died of AIDS-related causes. The quilt was displayed across the country beginning in 1987, when it was laid on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. At that time, the quilt was larger than a football field and was made up of 1,920 panels.

|

The AIDS Memorial Quilt currently includes over 50,000 panels. It is now considered the largest community art project in the world and can be accessed in full online.

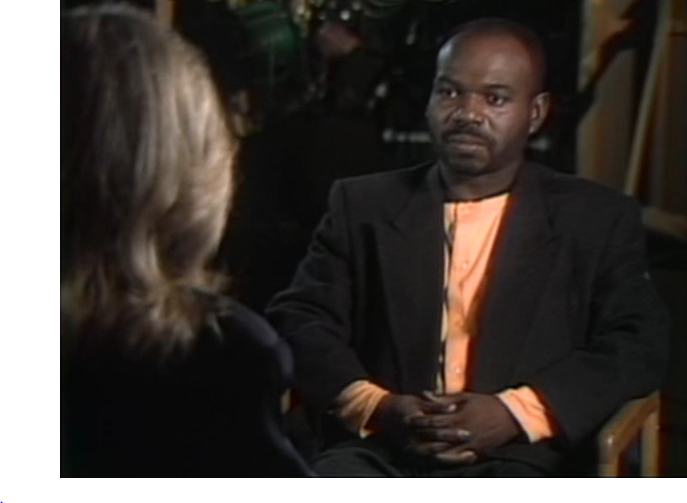

The Creative Mind, “Marlon Riggs” (KQED, San Francisco, June 19, 1991; June 26, 1991). Parts One and Two.

This episode of The Creative Mind, a KQED series featuring in-depth interviews with artists, includes a conversation with documentary film artist Marlon Riggs, who explored anti-Black racism and homophobia in his work. Riggs, a Black gay man, said, “I don’t constantly think of death, but I know that there will be a time, and for that reason, my work has been a way of not running from death or trying to undo death, which will come—I’m not afraid of that—but rather it’s living beyond death in a way that continues to move people, to show them that there is a reason for living, that humanity is something that can be—occasionally is—virtuous.”

|

Riggs discussed several of his films, including the controversial Tongues Untied (1989), an experimental documentary about Black gay men and the intersection of racism and homophobia. Riggs’s interview on The Creative Mind was broadcast a month before POV, a PBS series showcasing films by independent filmmakers, planned to show Tongues Untied nationally. When asked about the “shock value” of Tongues Untied, Riggs responded that he intended the documentary to affirm the experiences of his audience, which was primarily Black gay men. (For more on Tongues Untied, see the “National Programs” section below.)

“AIDS: Ten Years Later” (KQED, San Francisco, September 1991)

This program marked ten years since AIDS had been identified. By 1991, more than one million people in the U.S. were HIV positive, and 156,000 people had died. The program proclaims, “No longer affecting only gay white males, AIDS is spreading fastest among people of color and women.” The program discussed available HIV/AIDS treatments, FDA approval, the 1990 Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency Act, which was the largest federal funding approved for HIV/AIDS, and underfunded HIV/AIDS support services and staffing shortages. Many interviewees argued that the Ryan White Bill did not provide adequate funding to match the ever-growing number of people with AIDS, especially after the government began including gynecological symptoms in the definition of AIDS in 1991. Notable figures in this program include Dr. Mervyn Silverman, president of amfAR; Martin Delaney and Dr. Larry Waites of Project Inform; Dr. Sandra Hernandez, head of San Francisco Health Department AIDS Office; and Belinda Morse of Oakland’s Highland Hospital. The program also includes footage from ACT UP protests and covers ACT UP’s successes, like advising the government’s AIDS clinical trials group, pushing the government to include gynecological symptoms in the definition of AIDS, and accelerating the FDA drug approval process.

“AIDS Week Update,” At Week’s End (KNME-TV, Albuquerque, December 4, 1992)

“AIDS Week Update” includes interviews with women with AIDS and examines the issue of sex education for preventing children from contracting HIV. A panel discussion features Martha Trolin, AIDS Educator working with New Mexico AIDS Services, and Lorraine Compa, RN, who worked with Healthcare for the Homeless and AIDS education for sex workers.

“Women’s Educational Panel Promotional,” (KUNM, Albuquerque, June 17, 1994)

This educational radio program aimed to teach women how to protect themselves from HIV/AIDS, which was “becoming more and more a heterosexual disease,” and promoted an educational event at a Presbyterian Church in Albuquerque. Information was provided by Jeannie Boyle, member of the Board of Directors of the New Mexico AIDS Services, who coordinated the panel.

![On November 7, 1991, basketball star Magic Johnson announced that he was HIV-positive. Herbert Block. “Man, if it could happen to Magic—” Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, [LC-DIG-hlb-12376]. A 1991 Herblock Cartoon, © The Herb Block Foundation.](https://s3.amazonaws.com/americanarchive.org/exhibits/magic-cartoon.jpg)