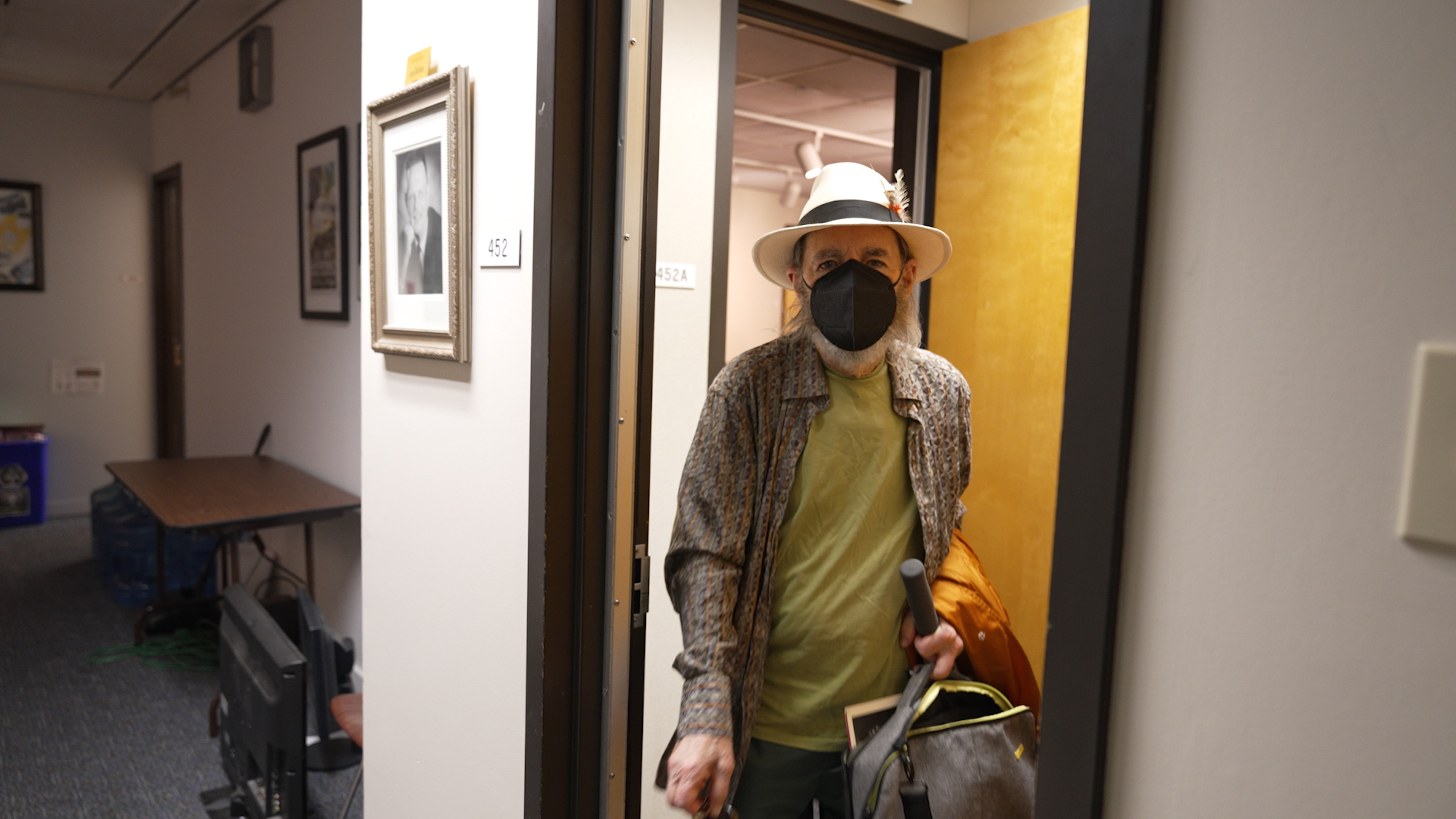

Harry Shearer’s Le Show: Sonic Portal to News, Satire, Memory, History

Le Show: Year One through Decade Four by Harry Shearer

For the AAPB, Harry Shearer wrote four short pieces about the evolution of Le Show over the decades, charting its development from the 1980s to the present.

Jump to:

Le Show: Year One

Le Show: Decade Two

Le Show: Decade Three

Le Show: Decade Four

Le Show: Year One

|

I had been working in radio as part of a daily satirical news series called The Credibility Gap when I got the opportunity to do a show of my own, mainly music, on a so-called underground FM station. That project ended when a newly-installed general manager with great flair fired the entire staff, seeing me off with a mock-sincere “I envy you your freedom.”

That freedom was returned to me on Dec. 4, 1983, when a friend who had a show on Santa Monica’s public radio station succeeded in convincing the general manager that I deserved a program on her station. That involved convincing her (and her music director) that my musical taste was sufficiently “eclectic.”

Such was the loosely-affixed brand of KCRW’s music policy. The fact I had previously been fired from a rock station for playing a Mel Tormé song wasn’t, apparently, sufficient proof of my eclecticism, but ultimately I was granted my golden E and got a two-hour time slot on Sunday mornings.

With that much time to fill, music was naturally a big part of the show’s content. I had by that point amassed a serious collection of LPs, and I was soon added to the “send this schmuck free records” lists of most of the labels. I called the show The Voice of America, because a) It sounded pompous and imposing, and b) I had a pretty good idea the U.S. government, which used the name for a shortwave radio service limited to overseas listeners, wouldn’t sue.

Central to each show were one or more comedy sketches, primarily parodies of shows and commercials I thought were particularly stupid or vile. I had by this point figured out a unique (AFAIK) method of recording multi-character sketches in which I performed all of the characters. Without divulging it in detail to you (although conversations about certain sums of money changing hands are always possible), the essence of the technique is simple.

Normally, then and now, when one person records multiple parts, they do so one character at a time; there follows a lot of editing to arrange the lines in order, to make it sound like dialogue. I wanted my sketches to sound like acting, in which each character is reacting to a line he/she has just heard. The scenes sound more “real” that way. Then and now.

Among hundreds of other concepts, this technique enabled my version of life in the Reagan White House. Based on the widespread premise that the President was fond of interrupting policy meetings to tell stories of life on the Warners lot, “Hellcats of the White House" premised that Ron and Nancy experienced world power as a series of B movies.

Six months in, I had found my groove and … I was in receipt of two job offers, either of which would take me far from Santa Monica. One was to become the first host of a public-radio morning news program; the second was to join the cast and writing staff of Saturday Night Live. Finally, I faced the fact that I wasn’t a serious person.

By the next summer, satirical tail between my legs, I returned to radio, one hour slimmer. And the program, after a fitful little competition, had a new name: a friend, who knew of my collection of photos of businesses which prefaced their names with the Frenchifying “Le” (Le Club, Le Hot Club, Le Hot Tub Club—all real), suggested Le Show, and it stuck.

Le Show: Decade Two

|

The first decade of Le Show ended with the George H. W. Bush years, immortalized on the radio on a series of supposed audio diary entries. Decade Two began with an even more intimate framework for Presidential satire, and a challenge.

The challenge was simply making fun of a Democratic President, something I hadn’t had, or been able, to do before. The framework was borrowed from a then-popular TV series based on the premise that “Boomers” were focused to an increased extent on their feelings. Thus, “Clintonsomething,” about two smart but seriously flawed humans who just happened to live in the White House.

The challenge was really to do Clinton satire without totally turning off the presumably leftish public-radio audience. This situation led me, for the first and last time in my career, to ignore my own First Rule of Satire—always believe the worst. That meant I was late to take the Monica Lewinsky story seriously, and therefore comedically.

Another of my satire rules came into play with one of the biggest domestic news stories of the 1990s—the O. J. Simpson double murder trial. That rule says you can make fun of anything, as long as your targeting is surgically correct. So, of course there’s nothing funny about the crimes themselves. But the trial generated a massive media circus, and those have always been comedy gold. Or at least two CDs worth of Le Show sketches and songs.

Florida, then as now, captured an inordinate amount of national attention, first with the story of a Cuban immigrant boy named Elian Gonzalez, whose father wanted him back on the island. Then came the Bush-Gore fight over the Presidential vote in Florida. I got enough material out of both stories to make the third and last CD of Le Show material, “Floridified!”

And then came 9/11. Certainly the biggest domestic news story since the assassinations of the 1960s, and followed, almost as if by plan, by a buildup for the invasion of a Middle Eastern country that had nothing to do with those flights.

The wave of media technology change had now made it possible to access news from sources far beyond New York and D.C. I was reading and hearing news from the UK and Australia, and so I knew the names of the three anti-proliferation officials in those countries and the US who were publicly warning, at risk of their careers, that the intelligence being peddled by Dick Cheney & Co. was bogus. No American media was sharing this information, so I decided that I would. And, from that decision sprang what a radio exec would describe as a lasting format change for Le Show—less music, more news.

Le Show: Decade Three

|

The seeming bifurcation of the Presidency—George W. Bush as the frontman, Dick Cheney as the guy behind the curtain—made for two continuing series on Le Show: a varying series of scenes featuring the Chief Executive, and “Dick Cheney: Confidential” featuring the veep as a 40s-style hard-boiled dick. What I particularly liked about that series was how well the instrumental sections of certain Steely Dan songs worked as the musical score.

It was first-rate déjà vu to be doing dark comedy about the Iraq war. The charade of what in Vietnam were known as the “5 o’clock Follies”—the daily US briefings in Saigon—seemed digitally restaged in Baghdad.

As the amount of music played on Le Show continued to decline, more and more of the continuing segments—“News of the Warm,” “Tales of Airport Security,” “Apologies of the Week”—gained musical introductions and/or underscoring. Aside from the mild amusement some of these sequences offered, there was the little advantage of offering the listener 10 or 20 seconds of relief from my speaking voice.

Le Show had reached its apogee of public-radio distribution. Stations in major cities—Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Chicago—dropped the program. It never was picked up in Boston—not a big college town, and a Washington, D.C. station ended Le Show’s brief tenure on their airwaves on September 10, 2001. Talk about timing!

Other stations, notably our San Francisco affiliate KALW, remained steadfast and loyal supporters. And the program’s longtime home station in Santa Monica did a sudden bailout just before our 30th anniversary. Probably just wanted to save the cake money.

Speaking of money: I’ve never taken as much as a cent in payment for doing Le Show. It dawned on me that public-radio money was never going to be worth breaking up the show for cleverly disguised ads. More to the point, it seemed more than linguistically obvious that the only way to be free to say and do exactly what I wanted on the show—to do a 40-minute conversation, or play whatever kind of music I chose—was to do it for free.

And then, again, the challenge not just of satirizing a Democratic President, but the first Black American in the White House. I think I recognized early that the promise Barack Obama made to Michelle—that he’d be home every evening for dinner with “the girls”—would, and did, prevent him from the kind of socialization with his party-mates in Congress that makes Presidents far more effective. So I created a series, parodying an early-TV hit, called “Father Knows Best,” where he’d explain his politics to one of his daughters.

Le Show: Decade Four

|

I have to admit, I imagined that folks in Hollywood, hearing Le Show every week on the radio, would come to a sudden realization: this would translate into a great TV show. So, the fact that I was still doing radio this many years into the gig was somewhat disappointing.

Actually, I did a pilot of a TV version, using a motion-capture technique to play all the characters in the sketches. It was received by the network head first with rapturous enthusiasm, followed a few days later by the dolorous news that it had a wider demographic appeal than expected.

No, it didn’t make sense to me, either.

And yet, I was grateful to still have this playground and platform; never more so than when Donald Trump first rode the down escalator and then rode the improbable path to 1600 Pennsylvania.

Most of my friends spent the next four years in a state of outrage, anger, and fear over the behavior and utterings of a man utterly unqualified for the job of President. I was lucky enough to have an outlet for my thoughts and feelings about a fellow I called “The Appresidentice.”

He was enough of a satirical inspiration that I finally got back to motion-capture animation, working with two Australian visual artists to do two music videos of songs—“Son in Law” and “Executive Time”—that originated, of course, on Le Show.