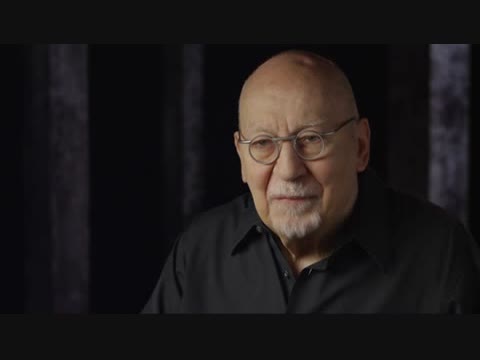

American Experience; 1964; Interview with George Lois, part 1 of 2

- Transcript

Thank you. Everybody ready? Yeah. Want your phones? Where were you when you heard about Kennedy? I was coming back from lunch at the four seasons restaurant which was one of my clients. With a couple of guys we had been enjoying the food and working at St. Tyne. I went by Roland Meladandri's clothing store. Roland Meladandri was the greatest designer of men's suits that ever lived. And we went by and we picked in and there were four or five people including Roland Meladandri was yelling something serious. We went in and that's when they told me.

It reminded me very much when I was a young boy and I was delivering flowers to my father's flowers and I was in the East Bronx and I got off a bus and there were people in the East Bronx howling, crying, sobbing with tears and that was when JFK, excuse me, when the fact that there were a voice about died. I mean it came to mind immediately when it happened. Yeah. What changed in America on that day? I think everything. I think everybody woke up. Everybody realized that maybe any goodness in the American way of life was on its way out. Really terrible shock. And we all knew, at least I remember,

knowing that when he went down there and that had been threatened, you know. And I think all we have said was that they go but not the best. They were in our minds to right wing. Turned out as well as on the left. Yeah, I mean, crazy story, you know. Hang on that's it. And as we tell people downstairs that we're delighted to join in on their conversation but maybe not today. One thing about this place is that you don't have a sound. Tell me about the kind of America,

almost the black and white, Aussie and Harry have kind of world that existed before that moment. Well, I mean, if you're talking about race, I did my basic training in 51 in the Jim Crow South. You know, I understood that there was racism in America. I grew up in the racist Irish neighborhood, which is redundant when I was young. And even though you knew about, even though you knew there were hanging black guys still hanging over, I was in the Jim Crow South in 51. My first experience, I was, there was a gold core of my company. I was a Camp Gordon Georgia. And took gold core Johnson, right here, Jackson, right here,

right here, lowest yo. And after the gold core, a major Southern major came up to me. He said, what's with the yo soldier? And I said, roll core, sir. He said, what's with the yo? I said, well, a sudden boy say, right here. And I'm from New York. So I said, yo. And he said, oh, and he almost had money to be in. He said, oh, another New York Jew-fair digger lover. Of course, my problem is I backed up a little bit and then I leaned in and I said, go fuck yourself, sir. And found myself in Korea, you know. Do you want to push your glasses back a little bit? Yeah. But no, I mean, I've been... It's so funny. I grew up on the standing racism. I was a Greek son of a Greek florist in a Irish neighborhood. And the racism there was beyond belief.

And my father hired a young black man to drive a delivery truck in his first little florist. And I probably wasn't a 41, 42, 43. And people would come in from the neighborhood saying, oh, Mr. Lois, we don't do that. And my father was, you know, no, no, no. And finally, we got a visit from the parish priest at St. John's in West Kingsbridge, who came in and told my father to get rid of the nigger. I wish Catholic priest. And my father said, no. And we lost their account because I used to bring flowers to them, deliver flowers to them every Sunday morning, you know. So, you know, and watching my father's Greek immigrant and watching his understanding of what racism was all about was the most thrilling thing in my life, you know.

I mean, it made me feel the way I feel to this day, you know. What were you doing in 1964? Well, I was in my... I started my air agency. I left the oil damper and back. I started the second creative agency in the world in 1960. And I was triggering what was called the advertising creative evolution at the time. So, I was a hot shot. I mean, the first air agency that had an architect is naming it. The first architect is before the oil damper and background. We just sit around with the thumbs up there, waiting for the copywriter and or account people to bring up the copy that they conjured up. And then they would do layouts, you know. And that's all right. The first second creative agency in the world, the first agency with an architect is naming it.

It's a young, young, ought director. I mean, I was on the top of the world, you know. And that's why the Esquire coverage that I've known for besides the creative evolution, how well Hayes, as the editor, was watching, was reading about me. And when he became the head editor, the first thing he did as he came to me, he asked me if I could help figure out how to do better Esquire coverage. So, you're running that company. What's the country that you're looking around at? What's America like at that one? Well, still stunned by the death of Jack, obviously, tremendous fear of the black man, you know, Elvich Cleaver, the black panthers. I did a Esquire cover in 1962.

I had liberal say in a major, you know. We all are trying to help the Negro with the civil rights. But, you know, they're going to look too far. So, I just shoved it down with the white Americans thought and I did a cover in 1960. The December 63 of the baddest motherfucker and black guy that ever lived, a sunny list and where the Santa Claus had, you know. And absolutely almost destroyed America. It was like an H-bomb hit America when that cover came out. I mean, senators, congressmen, screaming, talking about how Esquire was exacerbating the race war. So... Why was that such a huge one? Well, it's one thing to have. Esquire and I would have been in trouble. When I did covers like that for Harold Hayes, he would say, yeah.

So, he loved that kind of trouble. But, you know, we would have been in trouble showing Joe Lewis at the Santa Claus. But, sunny, motherfucking list in? Whoa! I mean, he was a convicted, you know, a really bad Esquire. So, this race thing was heating up hard, you know. And it was heating up because there were blacks who were starting to finally understand it. There were Malcolm X's at the time and they'd say, you know, screw the white man. You know, I mean, so they were making so much sense. I was about a million percent, you know. If I was a black guy back then, I would have been a terrorist, you know. So, what was Liston's M.O.? Why was he seen as so radiographic? Well, first of all, he was a labor goon. He was convicted of armed robbery. He was a sullen, you know, nasty. Everything, you know, you should be in life, you know.

When Cashe's Clay Sword, he said, that's the last black motherfucker America wants to see coming down there, chimney. Quoted quote, you know. He was always pretty good with words, you know. But what does it tell you that America right now was horrified by a black man wearing a Santa Claus hat? Well, first of all, the South was still fighting the Civil War. You know, Esquire lost, I think they claimed they lost nine accounts, advertising accounts, and they wore over southern mills, et cetera, et cetera, that immediately, you know, called up and said different. But it shocked everybody.

It shocked liberals. It shocked liberals. It shocked the most liberal person, you know. They said then they said, whoa, George. I don't think you should do that. Then why not? Well, I mean, what are you saying? What point did you make it? I said, what point did I make it? I'm shoving it down. Yes, vote if you think something's wrong with it. You know, a black Santa Claus, you know. I took the most extreme, you know. I mean, the next act, maybe if I had them dressed as Jesus Christ, it would have been worse, but not much worse, you know. Is that what you and Hayes and Esquire saw yourselves doing in 64? Oh, big time. No, I saw it. I started doing covers for Harold, October 63. 63, I think. And I knew, after I did the first one,

I get the cat and probably a cover that saved their life, but they were deeply in the red. I found out later. But I saw the covers as being one. I had to sell the magazine because they were in trouble. And it went over the years. I did the covers for Harold. It went from something like $40,000 to $2 million, gigantic success. But I saw it as a canvas to make my point politically. You know, I mean, I'd say to Harold things like early on, I'd say Harold, I think Muhammad Ali, when he became a Muslim, I think Muhammad Ali is a great American hero. He certainly not a trade. He's a great American. You agree with me?

And he was a Southern liberal thinker. And he'd say, yeah, what's on your mind? What do you mean? And I tell him what the first one I did about Ali was, I'm going to get the person in this world who most has a reason to hate Muhammad Ali to come out for him. And I take a photograph of my cover, and behind him I'll have Muhammad, you know, in his Muslim ghetto, you know, with his bow tie, keeping his knife shut behind him. And I said, yeah. Who? I said Floyd Patterson. He said, what? Because I'm- Muhammad slaughtered, he didn't slaughter Floyd, he was- he kept them alive so he could hurt him.

You know, instead of not going to mouth clean in the sector like third or fourth round, he just kept them standing so he could punish him, and debilitated him for the rest of his life. And because Floyd was saying, he used to call him Muhammad Ali, kept calling him clay, and he said things like, I got to bring the title back to America of Muslim-Kunton Shunpi champion. So Muhammad was furious at him, and he took it out of- I think that's great. Is it another cover in 64 of Kennedy? What was that? This was two years after the president was assassinated. Well, wouldn't it be two? It was in 64, wouldn't it only about it?

Well, not even a year, right? In November, 1963, Kennedy killed- No, in 1963. In 1963, yeah. Yeah, within a year, and it was a piece by Tom Wicker, and he called it Kennedy without tears. And I went the opposite way, and I showed a photograph of Jack of the president, and a man's hand dabbing tears off the photograph. And it either could have been the tear of the photograph crying or a tear coming from the man who was wiping the tear off. I still expressing the deep sorrow we all felt and still feel. It's funny the way people reacted to that.

They looked at it and looked away. It was a big cell, but it reminded them too much of the pain we were all feeling. Well, you got to understand. The other thing that was going on with me in 64, a lot was going on, but Bobby Kennedy and Steve Smith, his brother-in-law, came to me. Of course, my head's quite cold, I believe not. They didn't really know much about my advertising to work on Bobby's Senate campaign, which was a very tough campaign. He was a carpet beggar. Running against Keating.

Running against Keating. He had no rights in New York. He was a carpet beggar. Many liberals, half of them, more than half of them, still despised them because of when he worked with Roy Cohn on a Mac activity committee, his father kind of put him in the job. I think Bobby was pretty naive at that time, or has politically screwed up. He had liberals and a lot of Democrats say they'd never vote for him, and he was a carpet beggar. And I was still to work with Bobby. And I solved the problem basically, almost immediately, when I convinced him to start advertising early in June or June, they said, no, no, no, you can't, you know,

the campaign didn't start to accept him back then. And they said, no, no, let's start advertising now. The campaign, let's put Robert Kennedy at work for New York, and Bobby and Steve Smith said, oh, you're trying to say he's a carpet beggar, but who gives a shit? I said, you got it. And he worked. Let me ask you in this big picture kind of way. Here you are, lobbing these juicy bombs in these covers every once in a while. He's behind you. What are you fighting against? Who are you trying to wake up in America at that point? What's the country like that you're determined to rattle or shake up? First of all, racism, big time, you know, fighting racism. Second of all, fighting against a war that I knew was getting worse and worse and worse and worse. I did the first cover for Bob for Harold in 60.

A couple of months after I did my first cover, after I did my first cover, big success, he said, please, I got to keep doing them. I said, okay, I'll keep doing my running an air day to see. But like, if you get rejections, I don't, I think you'll be all right, but if you get rejections from, and that's group growth from the publisher that said it said, I can't do it. I mean, I have to do it with my clients, but I can't do it, okay? So you got okay on my covers. He said, deal. Two covers later, I showed him a cover, a photograph of a GI, and a copy said, and he's saying, I'm the 100th GI killed in Vietnam. Merry Christmas. And it wasn't a photograph of the 100th.

I didn't have the photograph, but I showed it to him. I said, we have to get it from the war department over here. And 100th GI. And he said, and he said, the war's going to be over. I had to do covers like three months before they ran back in those days, believe it or not. And he said, the war's going to be over by then. Everybody, everybody can't, every fashion said, oh, I'm going to get rid of this war. I got rid of this war. And he talked me into it. Maybe you're right, but I knew we were doing. All the time I worked for Howell Howell said, we should have run that cover. I'm talking about 100th GI. I mean, 58,000 men got killed after that, or more. The war was on my mind all the time. I got along great with Bobby Kennedy, but we had two terrible screaming fights about the war.

It was interesting to this day, you read books about Jack. And they all say, Jack was alive. He would have ended the Vietnam War. I don't think so. Because when I was working for Bobby, we had screaming fights about it. And George is the domino theory. Dean Hutchison, who's that deep? If Vietnam falls, and this falls, and then New York will fall, we had terrible fights. What do you think about him? He's an interesting part of our story. Mostly we're focusing on Johnson. And you're reminding me of a famous Johnson,

Barry Goldwater's advertising was, but Goldwater's advertising looked horrible. And Johnson does something amazing. What does he do? Well, he didn't do it. He didn't do it. I mean, Doyle didn't burn back to it. He said, if you don't vote, if you vote for Goldwater, it's the end of the world. Boom, you know. The little girl who did it. It only bad once, you know. One running. One's. One's. It bad once. That's the truth, Bruce, you know, I'm telling you. What made that ad so amazing? Why did it work so well? It was a great commercial. You know, great piece of propaganda. And by the way, maybe it's true, you know. I mean, Goldwater was awful.

Well, it's Raka, you know. It's a little girl. Fucking the daisy. Yeah. Fucking the daisy. Countdown. Countdowns. He ends up with the. With the bomb. He ends up with the. With the, you know, the ending of Dr. Strangelove, you know. You know, riding down on top of the. A bomb. And then the world, you know. And Johnson's not even in it. No, not at all. It doesn't mean mention him. He's just his voice. I guess he does. It just says pay four. Yeah. The thing about the. The. Bobby being for the war. I mean, in my. In my screaming argument, at one point I said, you and your fucking brother started that war, you know. You know what I mean? I said, wow. I said it. Um. In, um. Steve Smith who said you guys got to stop arguing about that war, you know. In 19th century, they were 67, but yeah, I didn't do some research.

I get a. I got a. Trying to stay in 64. No, but I'm just picking up talking about Bobby. I get a call from this, uh, from him. Secretary. A little Bobby. He said, George, shut up. Huh? Listen. I'm going downstairs to come out against the Vietnam War. So go fuck yourself and hang out. 67. It could have been late. 66. I forgot. Because he was about. Well, somebody's going to run president, you know. I mean, by that time, you know, by that time he. The country started to understand. And, and, and, and the reason one of the real great reasons companies. The country really understood was, uh, Muhammad Ali, you know. It feels like the step forward. You look at the Johnson ad and gold waters ads. What do they tell you about the country in 1964? The, the shifts that are going on.

The changes. Well, you got to stand in those days. They were, they were, they were. There were still, uh, drills that in schools that, that you. When the bomb hits, you get under your desk. You know, I mean, there's still people were building, you know, underground, uh, you know, uh, bunkers. I mean, it was the, it was the, it was the, it was the, it was just hope, this thinking that the world was going to end. You know, I mean, it, it was frightening. You know, and, uh, that's why the door of the end of it was so great. Because it just said, hey, if you're for the other guy, uh, we're all dead. You know, I mean, they have, they have good, good advertising. Um, and what do you, how do you think sort of Dr. Strangelove played into that? It was an amazing film that debuted in 1964. Oh, one of the greatest films ever made.

And the most timely ever, you know, I mean, it just, it just said, shit happens. I mean, the picture just said shit happens. So let's dig this over. You know, you got, you know, loony tomb guys and you got, uh, you, you got, uh, you got, you got, you're mine, sure. You know, with the start of Dr. Strangelove, you know, with the Germans. And he was, and it all had something, it all had some tooth to it. He was talking about the German scientist, you know, who, who, who, who now was my fewer and, uh, and the crazy, and the crazy general, you know, well, you know, George, you know, or she's Scott and, uh, and he's getting, he, you know, deciding not to get laid because he had to get to the, to the meeting. I mean, just a masterpiece film. It, it, beyond poverty, it was a, it said to everybody, shit happens. Kupeck was saying, it was a serious film. You know, nobody's ever made a more serious film than that in his,

in his, in his film. Um, did you ever hear about a film that, uh, the Goldwater campaign created, but didn't run. It was called Choice. It's, it's got, it's like an LBJ lookalike, not lookalike, but it's got a Cadillac running through dark streets. No, it is. Women's gyrating palvuses. Yeah. Blacks rioting in the street. Kind of heavy head, you know. It was really heavy. Yeah, yeah. Well, I mean, that's the difference from the great advertising and being heavy head. You know, great advertising, uh, you get away with murder. You want to make a political point, but you could do it with a, with a, with a, with a, with a, you know, creativity on your side, you know. And the guys are going out and do it, do it, do it, you know. Yeah. Yeah. Doesn't work. Um, Beatles arrive in America. Yeah, that was, uh, the, uh, my, in forobment with it, in a sense, is, uh, watching, uh,

watching it on a Sunday night, uh, at Sullivan, who, a couple of years before, had, uh, uh, introduced Elvis, only the camera didn't, wasn't higher than this pelvis. And, uh, and he, and I'm watching it with my wife, you know, on a Sunday night, and I said, I, I got, I, I said, that's, that's an Esquire cover. You know, you know what? I said, I'm going to get that settlement to, not, I'm not going to put it on. I'm going to get him to pose, wear it, uh, fucking Beatles way, you know, she said, good luck. Right? So the next morning, I called, I, on Monday morning, I called William Paley, the head of CBS. And the reason I knew him is I worked for him, and Dr. Stanton, when I came back from Korea in 1952.

Right. So I knew him well, and, like, Paley should tell everybody, I, you see that? Talk to people. Talk to them, CBS talk to them everything he knows, you know, that kind of guy. And I call him up, and I said, there's no one, and I told him what I want to do. I wanted to get, I told him to get a Beatles wig to happen. I said, you know, it'd be a fun thing to be saying that, I'm saying that Ed Sullivan is, is with the culture. He's on top of everything. He said, he's, he's funny. He's humorous. The last thing in the world that man was, was humorous, you know. And he said, ah, no, Lois. Now, George, hey boy. No, no, no, no, no. I love you ask my covers, but no way, no way you're going to make fun of one of my biggest shows, you know. Oh, I shouldn't have died, shouldn't have called him. So, I, sorry, the next day I went to the Ed Sullivan Theatre, and I had done the more key. I had designed the type and done the more key for, for, or was serious, the Ed Sullivan Theatre. And, waiting for them to come out. Right.

People were waiting there to, you know, just get all of this, and he came out and he put his work his way through, and then he gets to his car, and I'd sit there like a schmuck, standing like a schmuck, and I had a little sketch, and I said, I said, I said, Mr. Sullivan, my name was George, and I was like, do I have to cut a little, I want to get a pose of what he called me. He said, ah, terrific. What do you want me? I said, how about tomorrow morning at the clock? You know, terrific. It shows up, and he did it. Amazing. That's great. What are the Beatles due to the, to the America in 64? I mean, you look the footage now, and it's still kind of shocking the way that they... Yeah. Well, first of all, they looked... I mean, it was part of the hair phenomenon, too, you know? Although, most of the hair phenomenon I was crazy, crazy hair, and this, along came a hair that looked like a dinosaur soon designed it, you know?

But, you know, obviously, the talent was unbelievable. I mean, you know, you didn't have to love popular music. You didn't have to like popular music to know that their stuff was terrific, you know? And the fact that they were rymies and that they, they could take that, and they could sound more American than American singers. You know, I mean, it was a, amazing, amazing, strange group of kids, too. And their attitude about authority was completely... Yeah, especially that, and Lennon, you know, I mean, you know, good guy, good, obviously, a good guy, you know, wonderful guy. Yeah, you know, yeah. Anybody against authority is okay with me, you know? They go to, you know, we've talked to Sonny Liston's training camp, Liston says,

according to Robert Lipsack, says, I ain't proposing with those sissies. So they end up in Ali's... Oh, Ali loved him. He was clay then, yeah. Oh, yeah, he was... There's a photograph of him laying on the floor. Yeah, and another one of him, with all four of them at all. Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. Did you ever see my Ali rat book? Why didn't people say that it's the best book about Ali ever? I did. It's this thick, and this big, and it's... It's from the time... It... Coats from him from the time he was... From... From about his life, from the beginning of his life to now. You know, you know, 400 pages, you know. You got to get it there. Yeah. What was it about... I mean, you were talking about Sonny Liston earlier. What made clay different? And did America know what to do with it? What makes what? What made Tash's clay different? You were talking about Sonny Liston's image of a black man. Well, I mean, this incredibly narcissistic self-promota,

who was rhyming since he was 13 for sure, because when he was 13, and he was only fighting for a year, and the reason he was fighting is because his bike was stolen in Louisville, and he would go into the police station. And he said, I want to whip him. I'm going to whip the guy with him. And the police officer there said, a young man, if you want to whip me, you better learn how to fight, and he trained him how to be a fighter. Yeah, okay. But he... I forgot where to go. What was it about him, though? It was so shocking to White America. They didn't know what to make of it. They didn't know what to make of him, yet if you didn't laugh out loud at what things he said, something was wrong with you. You know what I mean? He just touched the humanity and the warmth and the funny bone of everybody. You know, when he did it with that poetry,

and a lot of it's damn terrific by the way, you know. But he couldn't have gotten away with it unless he had that incredible fighting style. I mean, if he just, if he fought, if he had the style of a Joe Lewis, he would have been that interesting. Yeah. I mean, it was the shuffle, and, you know, I mean, I mean, Dundee gets him... when Johansson would champion, Dundee convinces... Johansson... he was going to get in a ring with Patterson, I think, you know, who wasn't that... I had a lot of good movement, but not, you know. Yeah. I think left hook could defend your fighter. And he convinced him to let him go and for a couple of hours, it'll be good for you, you know. And Johansson, people said, no, we'll pay him, too. We'll pay the kid.

And he goes in, and he goes in, and after about a minute and 30 seconds, Johansson stops and gets his kid out of here, you know. Of course, he... I mean, just... Cassius just did a boxing lesson, you know, and boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom. Shuffle, shuffle, boom, boom, boom, boom. It was... Dundee said he was the most incredible thing you ever saw in his life, you know. Because he... I mean, he was sitting there saying, you're the world champion. You, Bert, you. I mean, you know, that's a... That's a guy who's an incredible confidence about himself. And, you know, which is what he was all about. And... He didn't sit the predictable...

- Series

- American Experience

- Episode

- 1964

- Raw Footage

- Interview with George Lois, part 1 of 2

- Contributing Organization

- WGBH (Boston, Massachusetts)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip/15-7p8tb0zp9j

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip/15-7p8tb0zp9j).

- Description

- Description

- It was the year of the Beatles and the Civil Rights Act; of the Gulf of Tonkin and Barry Goldwater's presidential campaign; the year that cities across the country erupted in violence and Americans tried to make sense of the Kennedy assassination. Based on The Last Innocent Year: America in 1964 by award-winning journalist Jon Margolis, this film follows some of the most prominent figures of the time -- Lyndon B. Johnson, Martin Luther King, Jr., Barry Goldwater, Betty Friedan -- and brings out from the shadows the actions of ordinary Americans whose frustrations, ambitions and anxieties began to turn the country onto a new and different course.

- Subjects

- American history, African Americans, civil rights, politics, Vietnam War, 1960s, counterculture

- Rights

- (c) 2014-2017 WGBH Educational Foundation

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:37:17

- Credits

-

-

Release Agent: WGBH Educational Foundation

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

WGBH

Identifier: NSF_LOIS_022_merged_01_SALES_ASP_h264 Amex 1920x1080 .mp4 (unknown)

Duration: 0:37:18

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “American Experience; 1964; Interview with George Lois, part 1 of 2,” WGBH, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed September 11, 2025, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15-7p8tb0zp9j.

- MLA: “American Experience; 1964; Interview with George Lois, part 1 of 2.” WGBH, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. September 11, 2025. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15-7p8tb0zp9j>.

- APA: American Experience; 1964; Interview with George Lois, part 1 of 2. Boston, MA: WGBH, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15-7p8tb0zp9j