The MacNeil/Lehrer Report; Internal Iran and Affect on U.S. Hostages

- Transcript

ROBERT MacNEIL: Good evening. Opponents of Ayatollah Khomeini revolted against his leadership today in Iran`s Turkish-speaking province of Azerbaijan. The rebels are followers of another respected religious leader, the Ayatollah Kazem Shariat Madari, who opposes the new constitution giving supreme power to Ayatollah Khomeini. Shariat Madari`s followers today seized the radio and television station in Tabriz, the capital of Azerbaijan, 350 miles northwest of Tehran. They said they would no longer accept Khomeini`s authority. Mass demonstrations in Tabriz today followed the shooting of two of Shariat Madari`s followers during clashes yesterday in the holy city of Qum. Ayatollah Khomeini visited Shariat Madari in Qum today and afterwards called on Iranians to unite and concentration their energies against the common enemy, the United States. At the same time, Khomeini sounded the first conciliatory note for many weeks. According to Foreign Minister Ghotbzadeh, Khomeini said Tuesday`s Security Council resolution was a step forward because it did not condemn Iran. The State Department welcomed this small hint of softening, but said the United States wanted to see action. Today is the thirty-third day of captivity for the fifty American hostages. Tonight: how will their fate be affected by the competing political and religious forces emerging in Iran, particularly the new rivalry between Khomeini and Shariat Madari? Jim?

JIM LEHRER: Robin, few Americans have thus far heard much about the other ayatollahs in Iran. There are six of the so-called grand ayatollahs, the holiest of the holy men for the Shi`ite Muslim population. Khomeini is the most powerful, clearly number one on the list. Number two is Ayatollah Shariat Madari. He, like Khomeini, is seventy-nine years old; he`s the leader of the Azerbaijanis, some four million of Iran`s thirty-five million total population. Shariat Madari is credited with having signaled the first public demonstrations which eventually led to the fall of the Shah. This was done while Khomeini was living in exile. Once Khomeini returned, Shariat Madari faded pretty much into the background. He has avoided any public disputes with Khomeini, although their differences have been well known. Shariat Madari, for instance, believed all along that once the revolution was successful, running the new Islamic republic should be turned over to secular officials. Khomeini, as events have clearly shown, felt differently. It was this basic split that led to Shariat Madari`s quiet opposition to the new constitution, which gave full and complete power to the religious leaders generally, Khomeini in particular. Also, Shariat Madari reportedly feels the constitution does not give enough local autonomy to the various regions within Iran, including Azerbaijan. Robin?

MacNEIL: One of the few people in this country who knows Shariat Madari well is Sepehr Zabih, chairman of the Department of Government at St, Mary`s College near San Francisco and research associate at the Institute of International Studies at the University of California at Berkeley. Dr. Zabih, an Azerbaijani by birth, has written extensively about Iranian politics. He was in touch with Shariat Madari`s followers by phone in Tehran and Tabriz yesterday and today, and he`s with us tonight in the studios of Public Television Station KQED in San Francisco.

Dr. Zabih, where does Shariat Madari stand politically in relation to Khomeini?

SEPEHR ZABIH: Well, at this moment, I would suggest that he is opposed to the recent policies of Khomeini in terms of his positions on policies and present issues. But I would say that in terms of his interpretations of Islamic laws and Islamic geology, he may be described as a more moderate and less politicized ayatollah.

MacNEIL: I see. Why does he oppose Khomeini? On what actual issue grounds?

ZABIH: Well, really for several reasons. I would suggest that his opposition began around the end of April or early May, when Ayatollah Khomeini decided that there was no need for electing a regular and perhaps 300-man constituent assembly to draft and approve a constitution. Ayatollah Khomeini, fearing that that kind of election would reveal perhaps the relative strength of other political and religious groups, decided instead to settle for a council or an assembly of experts. Now, this assembly at the end of last September changed the draft constitution so radically that it caused considerable annoyance, not only within the clergy but also within secular groups. So I suggest that the real origins of the difficulties, differences between the two dates back sometime around the month of May. Then I would suggest just one more thing, namely, in the recent crisis it is significant to note that of the six ayatollahs -by the way, not all of them are in Iran; one of them, perhaps the most prominent of them, is now in Najav -- of the five in Iran, five remaining grand ayatollah, or ayatollah ozma, only three, including Khomeini, came out supporting the taking of hostages. Two very prominent ones, Shariat Madari and Ayatollah Qumi in Mashad, remained silent; and in Iran, at this moment, if you remain silent, if you are a major ayatollah, it means that you are opposed to the policies of Khomeini.

MacNEIL: Does Shariat Madari have the power to threaten Khomeini`s hold on the country?

ZABIH: I would suggest that potentially the answer is in the affirmative, yes, he has. And I would say, really mention two reasons for what I just said. Number one, that other people, especially abroad, tend to for get that Shariat Madari played a very crucial role in unleashing the revolutionary momentum which overthrew the regime of the Shah in February. The second reason is that he`s extremely popular, not only amongst the Azerbaijanis but I would suggest that amongst a lotof secular groups; and indeed, there is even a political party which is called People`s Islamic Republican Party, which is not confined to Azerbaijanis; there are all kinds of secular groups which are affiliated with that political party. So I would say potentially yes.

MacNEIL: Can he leave Qum, the holy city, anytime he likes and go back to Azerbaijan?

ZABIH: Well, it seems to me that he`s under a kind of informal house arrest, but I would say that if he`s determined to go, I doubt that anyone could stop him.

MacNEIL: Does he share Khomeini`s anti-Americanism, apparent antiAmericanism?

ZABIH: I really doubt it, because I was in Iran in that crucial January of 1978, and I read an extended interview with Shariat Madari, in which, for example-- I give you one instance -- he suggested that we should not really ... the country should not go dry, we should not prohibit alcoholic beverages because we have a lot of foreigners who are helping us, who are involved in the economic development of the country. So I would say that the hatred which Khomeini is showing toward the United States is not shared by Ayatollah Shariat Madari.

MacNEIL: Do you know from your conversations with Iran whether the meeting that the two leaders had today went anyway to resolving their differences?

ZABIH: I don`t think it resolved the differences; I believe that the statement which was made fairly accurately described the situation. Ayatollah Khomeini denied that there were significant differences between the two. Ayatollah Shariat Madari as yet has not issued any statement indicating what went on. But I would suggest that in view of what Khomeini has said, namely an appeal to a sense of national unity, I don`t think the meeting went very well. Had it gone well, I`m sure that today the state controlled radio-television in Tehran would have bragged about the reconciling of differences between the two ayatollah ozmas.

MacNEIL: Well, thank you; we`ll come back. Jim?

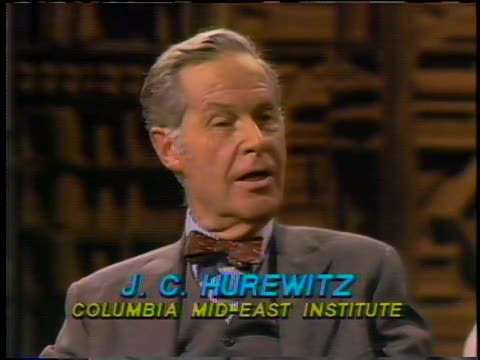

LEHRER: Let`s get another view now from an American expert on Iran. J.C. Hurewitz is director of the Middle East Institute at Columbia University; he has written widely on Iranian politics and frequently visited the country. How do you read this power struggle between Khomeini and Shariat Madari, sir?

J.C. HUREWITZ: I think that fundamentally what you have here is a process that seems to be continuous without much of a break, except from the outside, since 1921. You`ve had one-man regimes ever since the Shah`s father instituted his coup d`etat and then became Shah, and though there was a break for about a decade or so when the country was occupied by the Russians and British, in that period there was a bit of liberation of the system, then when Mossadegh came in in 1951 as prime minister, he did exactly the same thing that he was complaining about. And when he was replaced by the Shah who was recently overturned, Mohammed Reza, he in turn set up a single-man system, and this is essentially what you have at the present time. I don`t see any basic difference in the authoritarianism of Khomeini and the authoritarianism of the Shah. I`m astonished that the Pastaran, for example, the religious guard that has been set up to take over most of the police duties in the country, have installed themselves in Tehran in the very building that Savak evacuated. It`s this kind of condition, it seems to me, that we over here don`t fully understand.

LEHRER: Well, what about the new development, though, the relationship or the rift that has now come to fore between Shariat Madari and Khomeini? How does that fit into what might happen next, in your judgment?

HUREWITZ: Well, this is part of a pattern that we saw very clearly even before the seizure of the embassy. You will recall that at that time there was trouble in Kurdistan, in Khuzistan, Baluchistan, among the Turkmens up in the northwest; in every case the attempt to impose a centralized system, which is essentially what Khomeini`s been trying to do, has been resisted by these tribal groups, these ethnic groups, and fundamentally the reason for it is simply this: they were all opposed to the Shah and to the monarchy, but for them the overturn of the monarchy did not mean a return to Islam, it meant a return to autonomy.

LEHRER: Well, to take your earlier theory, that there is a desire to have a central figure, or an inclination to have a central figure, would these other diverse groups, both secular and religious -- the Kurds in cluded -- who now have grievances with Khomeini, would they be likely now to rally behind Shariat Madari?

HUREWITZ: Well, you must understand that in the first instance you`ve got a quarrel here among the Shi`i leaders. The Kurds and the Baluch and the Turkmens are Sunnis, and they don`t necessarily get involved in that kind of quarrel. However, it does have larger implications for the management of public affairs, and insofar as they can see any loosening of the central reins through siding with Shariat Madari, I think that they would very clearly support him and certainly they would support him in any case against Khomeini, at least for the tactical purpose of weakening Khomeini`s power..

LEHRER: Do you see this as a serious development, serious in terms of Khomeini`s control of Iran?

HUREWITZ: Yes, indeed. I think it`s a reflection of his inability to institute this single-man system in a form that is airtight. He doesn`t have armed forces that have redirected their loyalties to him; he doesn`t have the support of the secular leaders, as Professor Zabih has told us; he basically is operating within the religious establishment as his primary source, or as has happened as the fourth of November with the public excitement over the whole subject of the seizure of the embassy, he has had a means of focusing the public attention on that issue, deflecting them from internal problems.

LEHRER: Well, let me ask you the question in the most simple, basic terms. As you know, Khomeini has become understandably very much of a villain to Americans. Should what is happening in this split between Shariat Madari and Khomeini be seen as something that the average American could say, "Hey, look, that`s a good development; maybe there`s going to be pressure brought now on Khomeini to change his positions or even for him to fall out of power", or is it just too early to say that.

HUREWITZ: It`s a little too early to say that, though I think that any weakening of Khomeini`s influence at this juncture, his power and influence, is indeed an improvement in the situation from our viewpoint.

LEHRER: I see. Robin?

MacNEIL: The religious split complicates further what was already a complicated power picture in the hierarchy of Iran, centered around Khomeini himself. There have been changes in officials almost daily, some times weekly; it`s been difficult to ascertain at any given time who, if anybody, besides Khomeini actually exercised government power, or spoke for it. Here to try and decipher that part of the internal equation is Dr. Bahman Sholevar, an Iranian writer and psychiatrist now living in the United States who keeps in close touch with Iranian politics.

How can you explain the setup in Iran, in Tehran, in terms of the power wielded by different individuals and how the hostage situation is playing into that?

BAHMAN SHOLEVAR: I think the people who are in power at the present time in Iran, the major players have been hiding for some time behind certain other players who have left the scene. And right now we saw Mr. Bazargan leave the scene, Dr. Sanjabi leave the scene, major players for really National Front and former players of National Front; now you`ve seen the other faces come in, Mr. Yazdi came in, then Mr. Bani-Sadr came in, and for the first time we started seeing the people who were introduced as members of the Revolutionary Council, and it seems like there`s a lot of power play going on between these gentlemen. At present Mr. Yazdi seems to be a little bit out of the picture; Mr. Bani-Sadr is halfway there; Mr. Ghotbzadeh is there; Mr. Beheshti is there. And I think probably the lineup is now between Mr. Beheshti and Ghotbzadeh, about which one is going to be the first in line to be the president of the Islamic republic.

MacNEIL: Beheshti is another ayatollah who is a member of the Revolutionary Council.

SHOLEVAR: Yes, he is.

MacNEIL: Is he one of the so-called grand ayatollahs we`ve been hearing about, the six or seven, or is he a lesser ayatollah?

SHOLEVAR: No, he`s a lesser. ayatollah. Matter of fact, grand ayatollah has become a little meaningless now, because there was a time when ayatollahs were really chosen by some kind of consensus. The Shah, one of the things he did, he tried to break the monopoly, and -- am I supposed to be hearing this?

MacNEIL: The only thing you should hear at the moment is yourself, I think, but...

SHOLEVAR: I`m not hearing anything.

MacNEIL: You`re not hearing yourself. Well, we are, though.

LEHRER: That`s a good sign.

(Laughter.)

SHOLEVAR: No, he`s one of the lesser ayatollahs; matter of fact, nobody knew of him until -- he was the major person who apparently passed the tapes from France to Iran, and at that time...

MacNEIL: Which had the speeches and instructions of the Ayatollah.

SHOLEVAR: Of the Ayatollah, and as I said, a lot of these people wanted to hide behind the National Front, of which I happened to be the spokesman in the United States, and now they have had to come out and show their faces.

MacNEIL: You`ve just arrived late, having to come all the way from Philadelphia; I know that. We`ve been talking about the rivalry that came out so much into the open today between Ayatollah Shariat Madari and Ayatollah Khomeini. Do the National Front members, whom you represent in the United States, support Shariat Madari?

SHOLEVAR: Well, Shariat Madari is a leading religious figure, and he has his own following. Matter of fact, before Mr. Khomeini achieved symbolic significance in the revolution, Mr. Shariat Madari was probably the most prominent religious leader. And one of the things that the National Front does not espouse, certainly, is the fusion of the church and state, which is happening at this time, and it is a coalition of political parties. And it`s secular in nature. So as far as the Ayatollah Shariat Madari at present is opposing a kind of a new tyranny which is on its way to be established; and as far as National Front, among other political groups, is opposing that, I suppose they can again work together.

MacNEIL: Could you see Shariat Madari leading an opposing force to Khomeini which would actually threaten Khomeini`s control?

SHOLEVAR: Well, at present, I think, with the kind of constitution that they have passed, there are many, many threats to the ruling regime right now, because I think they made the mistake, and these are mostly people around Mr. Khomeini, who made the mistake of thinking that all they have to do is get on the top and stay on the top and make sure that they stay on. Matter of fact, on this same program a year ago I gave a warning that the danger would be that a particular group would try to get ahead and then try to exclude every other group; and that`s exactly the group I was talking about, people like Mr. Ghotbzadeh, like Mr. Yazdi.

I think their favorite line was, now that the revolution has succeeded, why should we let other people harvest? So the word "harvesting," as if the whole nation really was there for a group to get there and harvest. And they`re finding out that there are a lot of people who are very, very disenchanted, very disillusioned, and they`re going to oppose it. And again, to the degree that Ayatollah Khomeini would become now the symbol of the new constitution, he will lose some of the support that he has enjoyed when he was the symbol of a fight against tyranny.

MacNEIL: Thank you. Jim?

LEHRER: Dr. Zabih, back to you first, sir. You know Ayatollah Shariat Madari. Is he the kind of man who would lead an open rebellion against the Ayatollah Khomeini?

ZABIH: Maybe not personally, but he is the kind of man who could give his blessing to a secular leader. I want to characterize his political behavior in the following fashion: he`s an ayatollah who believes that the role of the clergy is to educate people in religious obligations; the clergy belongs to the mosque; that you become political, you become actively militant, only as a last resort. This is precisely what he has done; that is to say, it was only in January of `78 that he became a militant, anti- Shah ayatollah ozma. So I would suggest that it depends really on circumstances. But I would like to mention that he could give his blessing to one man or a group of people, political party, and achieve the purpose of opposing and challenging Khomeini.

LEHRER: Is he likely to do that?

ZABIH: Much depend on Khomeini`s reaction. I would suggest that Khomeini may move in two directions. By instinct he might sound even more militant, more anti-American, appeal to a sense of unity at a time of danger; or he might be realistic enough to acknowledge that he has made some mistakes, that he has imposed this constitution and the question of hostages played into his hand for the purpose of consolidating his hold on Iran.

LEHRER: Professor Hurewitz, should we read this problem that`s developed between Shariat Madari and Khomeini as -- how does this in any way impact on the central question, which is, for the world, the release of those hostages? How could it in any way affect their release?

HUREWITZ: Well, it seems to me that we have to sit this one out for a while longer. I have a feeling that we may have to sit this one out until they actually set up a government. They don`t have one yet, they`ve just approved a constitution. They`re operating even without a prime minister at the moment, which means that there is no coordinator there; you hear many voices almost every day.- One says that we will accept no dollars for the sale of oil, and the next one says, yes, we will. And it goes on like that on almost every issue. So that without full coordination it seems to me Khomeini himself is a captive of this situation. I don`t think he`s on top of it at all.

LEHRER: Mr. Sholevar, let me ask you: how would you relate what`s happening there now internally to the release of the hostages, in terms of the Shariat Madari/Khomeini problem?

SHOLEVAR: Well, the question is that, of course, if I do not think that the people around Mr. Khomeini did get the support that they had hoped, that with all the coincidences -- that it was the kind of anniversary of the revolution, it was the height of the religious feelings in the country, and also the anti-American feelings that were expressed -- and the taking of hostages could not have helped but unify certain factions who in other respects were disenchanted behind, again, the present regime. But they did not really get the support, because they talked about sixty to one but they did not say how many people really voted. And that means that they might not be as strong as they had hoped to be to deal with the...

LEHRER: So it`s a hopeful sign; in a word, yes?

SHOLEVAR: I don`t know, it might prolong the things.

LEHRER: Oh, I see. All right. Robin?

MacNEIL: I`m sorry, but we have to leave it there. Thank you, Dr. Zabih, for joining us from San Francisco. And gentlemen, thank you. Good night, Jim.

LEHRER: Good night, Robin.

MacNEIL: That`s all for tonight. We will be back tomorrow night. I`m Robert MacNeil. Good night.

- Series

- The MacNeil/Lehrer Report

- Producing Organization

- NewsHour Productions

- Contributing Organization

- NewsHour Productions (Washington, District of Columbia)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip/507-5d8nc5t061

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip/507-5d8nc5t061).

- Description

- Episode Description

- This episode features a discussion on Internal Iran and Affect on U.S. Hostages. The guests are J.C. Hurewitz, Bahman Sholevar, Sepehr Zabih. Byline: Robert MacNeil, Jim Lehrer

- Date

- 1979-12-06

- Asset type

- Episode

- Rights

- Copyright NewsHour Productions, LLC. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode)

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:26:02

- Credits

-

-

Producing Organization: NewsHour Productions

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

NewsHour Productions

Identifier: 5114P (Show Code)

Format: Betacam: SP

Generation: Master

Duration: 0:00:30;00

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “The MacNeil/Lehrer Report; Internal Iran and Affect on U.S. Hostages,” 1979-12-06, NewsHour Productions, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed July 16, 2025, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-507-5d8nc5t061.

- MLA: “The MacNeil/Lehrer Report; Internal Iran and Affect on U.S. Hostages.” 1979-12-06. NewsHour Productions, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. July 16, 2025. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-507-5d8nc5t061>.

- APA: The MacNeil/Lehrer Report; Internal Iran and Affect on U.S. Hostages. Boston, MA: NewsHour Productions, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-507-5d8nc5t061