The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer

- Transcript

MR. LEHRER: Good evening. I'm Jim Lehrer. On the NewsHour tonight, the President signs telecom reform into law; we do a what now with FCC Chairman Reed Hundt; moving football teams from city to city, Tom Bearden reports, Elizabeth Farnsworth runs a discussion; we end our series of Republican stump speeches with businessman Morry Taylor's, and where have all the mysteries gone wonders essayist Roger Rosenblatt. It all follows our summary of the news this Thursday. NEWS SUMMARY

MR. LEHRER: President Clinton signed a Telecommunications Bill into law today. He did so at a ceremony in the main reading room of the Library of Congress. It included leaders from both parties who helped move the bill through Congress. The new law permits long distance companies to get into each other's business, and it ends federal controls on many cable television rates. It also requires television makers to install chips that let parents screen out violent programs. The President hailed the cooperation that led to the legislation.

PRESIDENT CLINTON: This historic legislation in my way of thinking really embodies what we ought to be about as a country and what we ought to be about in this city. It clearly enables the age of possibility in America to expand to include more Americans. It will create many, many high-wage jobs. It will provide for more information and more entertainment to virtually every American home. This bill is an indication of what can be done when Republicans and Democrats work together in a spirit of genuine cooperation to advance the public interest and bring us to a brighter future.

MR. LEHRER: One of the law's segments was immediately challenged in federal court in Philadelphia. The American Civil Liberties Union and 19 other groups asked the court to suspend the provision banning indecent speech on computer networks on grounds it is blatantly unconstitutional We'll have more on the Telecom law right after this News Summary. On another communications matter today, the Federal Communications Commission approved the Disney Company's takeover of Capital Cities ABC. The FCC gave Disney a year to sell or swap some of its media properties to comply with various federal regulations. White House Spokesman Mike McCurry said today President Clinton received insurance payments to cover some of his legal bills. The money came from two umbrella liability policies the President took out several years ago.

MIKE McCURRY, White House Spokesman: He bought these policies, as did many people in professional life who are more susceptible to facing lawsuits. That happens to a lot of people who are prominent both in private sector and public sector. He understood that there might be payments that would come pursuant to those policies, but he also knew that his legal bills would far and away exceed any coverage that those policies would render.

MR. LEHRER: The "Wall Street Journal" reported today insurance policies gave Mr. Clinton $900,000. The money will help defray the cost of a sexual harassment suit filed against him by a former Arkansas state employee. On the budget story today, House Speaker Gingrich said there could be a deal in March. He said the recent bipartisan agreement among the nation's governors on Medicaid and welfare reform was the reason for his optimism. He spoke to the American Association of Retired Persons.

REP. NEWT GINGRICH, Speaker of the House: The governors, I think, were very helpful this week in adopting by a unanimous vote on welfare, Medicaid, and job training some very real reforms. I think that helps move it, so I wouldn't be too surprised to see a bill that sometime maybe in March actually gets signed. I don't know how we'll get there yet, but I can see the beginnings of a real opportunity here to put together a pretty good program.

MR. LEHRER: The Speaker said welfare and Medicaid reforms could be written into a balanced budget package, or they might be added to the debt limit extension expected later this month. In Oregon today, heavy rain and melting snow produced the worst flooding in more than 30 years. At least two people were killed, thousands forced from their homes. Hundreds of roads have been closed, as well as government offices and schools. Authorities said in the Northwestern part of the state nearly every river and stream was above or near flood stage. In Bosnia today, the Bosnian Serb army suspended all contact with NATO peacekeeping forces. The Serb commander said no further meetings would take place until the Bosnian government releases several Serb officers. They are being held at the request of the International War Crimes Tribunal. A State Department spokesman said Assistant Secretary of State Richard Holbrooke will try to mediate the dispute. Holbrooke was the principal U.S. negotiator of the Dayton Peace Accords. And that's it for the News Summary tonight. Now it's on to implementing the telecom law, moving football teams, a Morry Taylor stump speech, and a Roger Rosenblatt essay. FOCUS - UNPLUGGED

MR. LEHRER: We go first tonight to the new world in which the telecommunications industry operates. President Clinton signed it into existence today. Margaret Warner begins our coverage with this set-up report.

MARGARET WARNER: It was quite a scene today in the Library of Congress main reading room when comedian Lily Tomlin made an appearance via the Internet.

LILY TOMLIN: You hoo, Mr. President. Mr. President, you hoo. I can just see the headlines, "Bill Signs Bill."

MS. WARNER: After the humor and high tech fanfare, President Clinton signed into law a mammoth bill that will restructure the entire telecommunications industry. Congress has been trying to pass such legislation for almost a decade. The new law transforms the legal frame work that regulates the telephone, broadcast, and cable TV industries, breaking down barriers erected by communications law adopted more than 60 years ago.

PRESIDENT CLINTON: Today, our world is being re-made yet again by an information revolution, changing the way we work, the way we live, the way we relate to each other. But this revolution has been held back by outdated laws, designed for a time when there was one phone company, three TV networks, no such thing as a personal computer. Today with the stroke of a pen our laws will catch up with our future. We will help to create an open market place where competition and innovation can move as quick as light.

MS. WARNER: More specifically, the new law will allow long distance and local phone companies to compete in each other's markets. These companies also can begin to offer video services over their phone lines, competing directly with cable providers. For their part, cable operators may now jump into the phone market and federal controls on cable TV rates will be lifted immediately, or within three years, depending on the size of the market. The bill's reach extends further. For broadcasters, it relaxes the limits on the number of TV and radio stations a single company can own. At the same time, it requires TV sets to be equipped with a device known as the V-chip to give set owners the option of automatically blocking violent programs. Finally, for on-line computer companies and users, the bill imposes criminal penalties for knowingly transmitting "indecent" material to minors. In a clear signal of what's to come, President Clinton signed the legislation a second time with an electronic pen on a computer screen which instantly posted the new law on the Internet.

MR. LEHRER: Now, to the man who has much responsibility for making all of this work. He's the chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, Reed Hundt. Mr. Chairman, welcome.

REED HUNDT, Chairman, FCC: Thank you very much.

MR. LEHRER: Many words have been used today and before to describe what this bill or this law means to telecommunications in this country. Tell us in your words in an overview what this means.

MR. HUNDT: I'd call it the "Invest in America Act," because the purpose of this bill is to open all communications markets to competition and all the businesses as a result of that will be investing even more in our communications sector. The second investment we'll be making is in job creation, because that competition will cause overall a growth in jobs. And the third investment that this new law makes is in our children because this new law makes real the promise that the President asked us to all arise to in the State of the Union in '94 and again in '96, specifically the promise to put communications technology in every classroom of every school of every county in this country.

MR. LEHRER: So this--the words--the sweeping words are justified?

MR. HUNDT: The sweeping words are justified. The communications sector is the big driver of our economy right now. It makes productive all of our businesses. It's a seventh of the economy going to a sixth, going to a fifth, to get right our policies in this part of the economy is crucial to the country's success in the 21st century.

MR. LEHRER: All right. Let's go through some of the specifics and, for instance, the first one, long distance, local phone companies can get into each other's business. They can just go do that tomorrow?

MR. HUNDT: No. As you can well imagine, it's necessary for the FCC to write detailed rules of competition in order to give people a chance to compete in the currently monopolized Bell Company markets. That's a big job we have to do at the FCC in the next six months.

MR. LEHRER: Six months?

MR. HUNDT: Six months for writing the rules of competition in the local telephone market.

MR. LEHRER: So if somebody wants to--is interested in the possibility, not necessarily the reality but the possibility of their being able to choose between two local phone companies, the one that's there now and another one that's coming in, how long-- conceivably how long could that be in the best scenario?

MR. HUNDT: Businesses can go into these markets right away, and you're going to see some people get started right away, but to really be successful in competing with the Bells, any business, whether it's a long distance company or cable company is going to need us to write rules of competition that allow the new entrant to connect to the existing networks, to allow the new entrant a real chance to compete.

MR. LEHRER: The key to it is there's not going to be a--there's still only going to be one line coming into your house, right?

MR. HUNDT: No.

MR. LEHRER: No?

MR. HUNDT: No. There's no telling how many lines there will be.

MR. LEHRER: Is that right?

MR. HUNDT: There aren't going to be any rules on these things. We're all going to have to get used to the fact that the future is not going to be predictable, and it isn't going to be set by the big government model anymore.

MR. LEHRER: In other words, you could have a telephone line for long distance calls, you could have a telephone line for local calls?

MR. HUNDT: You could. It's probably not likely. I think what's more likely in some homes is that you'll see different companies come to you and offer bundled products. They'll say, try me, I'll sell you your cable service and your local phone service and your mobile phone service and your long distance and I'll give you the whole package at a real nice price, and then somebody else will say, no, no, try me, I'll give you the same package, and I'll give you a coupon for VCR tapes as well. I mean, that's the kind of competition we're likely to see. There's no telling how many actual wires or connections people will extend to your house. The first thing you'll see when the rules really get written and people really get started is that there will be different kinds of product offerings presented to customers.

MR. LEHRER: Now, the second thing is that they can also use their telephone line for video. Is that--is that ability already there in the telephone line? Is this going to require something new as well?

MR. HUNDT: Well, lots of invention is necessary before it's economically practical to use a cable line and the telephone line to deliver the opposite service, but what this bill says, I guess what this law says, is go ahead and invent, there are not going to be any legal prohibitions on what you can do with your invention.

MR. LEHRER: So a cable company that wants to go into the telephone business, they--let's say in a city, a particular cable company has already wired this city for cable, and what's involved in their going into the telephone business as well?

MR. HUNDT: Well, of course, today's cable line isn't going to deliver a telephone call because it wasn't built to do that. So they would have to rebuild that line, or the cable company would have to go out and contract with a wireless company and offer you wireless service. Now, you're going to see all of these things happening. You're going to see cable companies in alliances with wireless companies and offering you wireless and cable. You're also going to see cable companies knocking on your door saying, buy this little box, it's called a two-way modem, it'll give you Internet access over your cable line. That's going to be a big hot product that you're going to see.

MR. LEHRER: Why? Why is that going to be such a big deal?

MR. HUNDT: Because Internet access is a booming market, because- -

MR. LEHRER: That's already been proven. That's already there.

MR. HUNDT: Well, we're finding it out right now.

MR. LEHRER: Yeah.

MR. HUNDT: We didn't know it a year ago, but we're finding it out right now, and the main thing about this law is that it permits us at last to open the doors to uncertainty, but also to invention and creativity, so it isn't going to be government that's going to be answering the questions you're asking me. It's going to be competition in the marketplace that's going to answer these questions.

MR. LEHRER: But you still have to write all these regulations. Isn't that kind of a--isn't it an oxymoron, we're going to deregulate this industry but nothing can happen until you all write the regulations?

MR. HUNDT: Here's the change. For 60 years, the FCC and its counterparts at the state level have been the supervisors of monopolies. We've been regulating the prices. We've been looking at the books. We've been telling them what they could do and what they couldn't do, and that era is over. It's just like what the President said in the State of the Union when he said the era of big government is over. Our role now is not to be the supervisors but to be sort of the judges of competition, to write some simple, fair, clear rules that'll make competition real and not just rhetoric, but, otherwise, to get out of the supervisory role and let businessmen and business women make the decisions they need to make in competition in the marketplace.

MR. LEHRER: What's the single most difficult and important rule that you must write and assume?

MR. HUNDT: Can I give you two?

MR. LEHRER: Sure. Give me--

MR. HUNDT: The first is this. Over the next six months, we need to get right the country's policies for allowing different companies to connect to each other's networks.

MR. LEHRER: Explain what that means.

MR. HUNDT: All right. For example, Bell Atlantic, great company, has this huge network all over this region around Washington and a bunch of other states.

MR. LEHRER: But it's still--it's local, mostly local telephone, right?

MR. HUNDT: It's all local telephone.

MR. LEHRER: Okay.

MR. HUNDT: It reaches essentially 100 percent of all homes, and they make and receive 99 percent of all the telephone calls made in this area. Now, if I want to go into the telephone business against Bell Atlantic, I might be able to sell that service to you, but you want to be able to connect the line I just sold you to the Bell Atlantic network, so that you could make the call but have it go to a Bell Atlantic customer. You don't want to say, well, you can't call anyone, because you're the only customer--because you're on my phone company.

MR. LEHRER: You're on one company and I'm on another.

MR. HUNDT: Yeah.

MR. LEHRER: But I want to call you.

MR. HUNDT: So you need to have the lines connect. You need to have two competing networks connect. Everybody knows that you need to do it.

MR. LEHRER: So you have to come up with a rule that doesn't hurt Bell Atlantic, at the same time helps the competitor compete against 'em?

MR. HUNDT: That's exactly the challenge.

MR. LEHRER: How in the world are you going to do that?

MR. HUNDT: Well, we're going to ask everybody their views, we're going to force 'em all to debate it in front of us, and we're going to make a fair call within six months.

MR. LEHRER: So the idea, though, is that Bell Atlantic will take a hit. We're using Bell Atlantic as an example, but Bell Atlantic takes a hit, because they have to share that, and, and potentially be competed against--but they have free--if they want to go and go into the long distance business, but that's a whole different ball game--how in the world are they going to go into the long distance business overnight?

MR. HUNDT: Long distance is a different challenge here. Now, what we're saying is, Bell Atlantic, you have a monopoly network, and you need to open it so people can connect to it. That's a narrow market.

MR. LEHRER: Okay.

MR. HUNDT: As to long distance, we're saying, Bell Atlantic, as soon as you comply with these fair rules that open your own market, then we'll consider letting you into the long distance business. Now, that was the basic compromise that the law reached. That's what got the big votes in the House and the Senate, and that's what we have to implement.

MR. LEHRER: But as a practical matter then, let's move on to say AT&T--

MR. HUNDT: Sure.

MR. LEHRER: Or Sprint, or one of the long distance companies. What do they get in exchange for letting say Bell Atlantic--do they have to let Bell Atlantic come in and use some of their lines and some of their switches and networks and stuff?

MR. HUNDT: When Bell Atlantic or any telephone company demonstrates that it's complied with the basic rules of opening themselves to competition, then they get to go into long distance. What the long distance companies get out of this is the chance to compete in the local phone markets where they have been prohibited over thelast ten years.

MR. LEHRER: But how does, as a practical matter, how does Bell Atlantic get into the long distance business without going into business with one of the existing long distance companies, without having to wire the whole country?

MR. HUNDT: Well, lines run everywhere so you can make alliances, you can build your own systems, you can partner up. Finding potential opportunities to build networks is not really going to be the problem here.

MR. LEHRER: Partner up. All right. Is it possible say for a Bell Atlantic to partner up with an MCI, partner up with a large cable company, or a local cable company, and maybe a, an on-line company and do it all one big deal?

MR. HUNDT: What you're asking here is the question of the moment. All the different businesses are trying to figure out which alliances are best for them in the competition that is exploding as of about five hours ago. And it is definitely occupying everybody's late-night hours in the headquarters of the companies and the Wall Street financiers are trying to figure out which venture is the best one to bankroll, and this is the excitement and the exhaustion of competition.

MR. LEHRER: But what, the question--there is nothing, no rule that you're going to write that's going to prevent that from happening, is that right? In other words, this law says that such, that these partner up things up any combinations are possible?

MR. HUNDT: Well, the Department of Justice and the FCC are going to do their darndest to make sure that we don't let monopolies get re-constituted. But having several different, lots of different businesses compete to build national or regional networks and compete against each other, that's a good thing. That's more choice, and that gets back to what I was saying before, that's investment, that's jobs, and then the second thing you let me say I can tell you was the most important part was the part of the law that gives us the ability for the very first time to create incentives that will guarantee that communications technology is in every classroom of every school in the country. Now--

MR. LEHRER: How do you do that?

MR. HUNDT: Well, we haven't developed all the techniques yet, but the law gives us a range of different tools. This is a very important provision. Credit needs to go to Senators Rockefeller and Snow and Kerrey and Exon who authored it on the Senate side. Acknowledgements need to go to the President who asked for it in the State of the Union and if you let me say so, we need to hark all the way back to Sen. Gore, now our Vice President, who talked 20 years ago about building the information highway from Carthage, Tennessee, to the Library of Congress. For the very first time, we have a law that permits us to create incentive schemes that will give companies a financial motivation to put their networks right into classrooms.

MR. LEHRER: Wow! We've just scratched the surface here, but before we go, the V-chip thing, this is something that, all right, the law requires all new television sets to have V-chips. Let's say that I have a TV set and I have small children, I want 'em to watch violence tomorrow, can I go out and buy a V-chip and put it in my TV?

MR. HUNDT: Well--

MR. LEHRER: My existing TV?

MR. HUNDT: You can go and do that, but what's missing right now is a commitment from broadcasters to give us ratings about their shows. It's still necessary for somebody to describe the show in this cyberspace world of transmissions so that the chip in your TV can identify it as inappropriate for kids. Now, that's one of the- -

MR. LEHRER: The chip is actually--oh, oh, this is dirty, boom, turn it off?

MR. HUNDT: The chip will read whatever information is sent to it, so if the broadcaster says this show is inappropriate for kids, too much violence, then the chip would turn it off. Now, what we're talking about here is very simply let's give parents the power to choose and something to choose.

MR. LEHRER: But do those chips exist now?

MR. HUNDT: Yeah. The chips exist.

MR. LEHRER: And so what does not exist is the stuff that the chip has to--bad word--that the information that the chip has to read in order to react.

MR. HUNDT: Exactly right.

MR. LEHRER: Is the chip expensive?

MR. HUNDT: No. The chip isn't expensive, but it really will only be truly portable when it is in every television so that the economy is a scale, you know, lower the price to a dollar or two. But, as I said, the missing element here is the country needs broadcasters to say, yeah, if the technology is there, we will give you the information, we will voluntarily describe our shows the same way the movie industry describes the movies.

MR. LEHRER: Mr. Chairman, thank you, and good luck.

MR. HUNDT: Thanks a lot. FOCUS - TURF WARS

MR. LEHRER: Still to come on the NewsHour tonight, moving football, teams, a Morry Taylor stump speech, and a Roger Rosenblatt essay.

MR. LEHRER: Elizabeth Farnsworth has the football story.

ELIZABETH FARNSWORTH: Tomorrow, National Football League Team owners are scheduled to vote on an issue that has the city of Cleveland up in arms, a plan by the Cleveland Browns to move to Baltimore. Tom Bearden begins our report.

TOM BEARDEN: December 17th was a very dark day for Cleveland. Angry football fans hung in effigy Cleveland Browns owner Art Modell outside the stadium. Inside, cheering fans brandished signs saying, "Nobody Back Stabs Cleveland," and "Rot in Hell, Modell." The city's beloved Browns, one of the foundation franchises of the National Football League, played what could be their last game in Cleveland. After the final gun, some fans ripped out the seats to take home a souvenir.

FEMALE FAN: What's Cleveland without the Browns? What's Cleveland without a football team at all?

MALE FAN: You might as well stick a knife in the backs of the community and twist it, my opinion.

MR. BEARDEN: And that's now most of Cleveland felt on November 6th when Modell unexpectedly held a press conference with Maryland Governor Parris Glendening to announce that the Browns were moving to Baltimore.

GOV. PARRIS GLENDENING, Maryland: [Nov. 6th] Ladies and gentlemen, we have a signed contract in hand. [applause] The Browns are, indeed, coming to Baltimore. [cheers and applause] We are standing on the very spot where in less than three short years I believe 70,000 cheering fans will be cheering for Maryland's new team, the Baltimore Browns. [cheering and applause]

MR. BEARDEN: The trouble is more than 70,000 fans have been cheering the Browns for almost five decades in Cleveland. Their zeal is legendary in the NFL. One of the end zones is known as the "dog pound." Thanks to television, it's denizens are world famous. Barking at opponents, tossing dog biscuits on the field. In this steel mill town, football is serious business. The Browns are an integral part of the city's social fabric. Bob Grace is co-chairman of a fan organization called "The Browns Backers."

BOB GRACE, "Browns Backers": This is something that is bred into our community from the time kids are little. It's something that we can hand down to our children.

MR. BEARDEN: Why would the owner of a team with that kind of loyalty want to move? For one thing, Cleveland's football stadium was built in 1931. It's very expensive to maintain, and it lacks the amenities and the income of the much newer baseball and basketball ventures that just opened last year. Those new facilities became a sore point for Art Modell. For example, the new home of the Cleveland Cavaliers has luxurious sky boxes equipped with all the extras. They bring in $175,000 apiece every season. The cash flow is vital in maintaining a competitive team as players' salaries head for the stratosphere. In the old football stadium, the premium boxes brought in only $50,000, and Modell was feeling the pinch as he was forced to pay his players ever-higher salaries. Browns owner Modell told the city that the changing economics of professional sports demanded he get a new stadium as well. Mayor Michael White thought the Browns' contribution to Cleveland's economy also required the team stay in town. He says the millions of dollars that Browns' fans spend result in thousands of jobs.

MAYOR MICHAEL WHITE, Cleveland: It contributes 47 million dollars to our economy's bottom line. That number is growing. It's a part of a brand new entertainment venue that includes the Rock'n Roll Hall of Fame, the Science and Tech Museum. It is an entity that is part of our selling program, to especially the best and the brightest around the country, when we talk about Cleveland being a Major League city. It also carries our moniker all over the world.

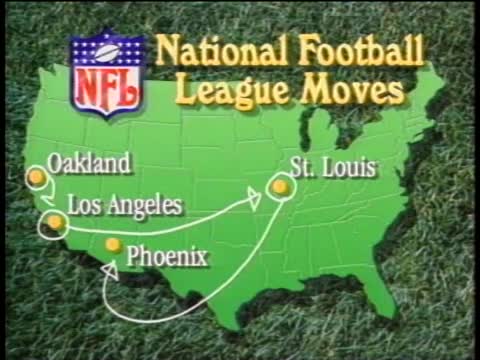

MR. BEARDEN: But according to Modell, local politicians didn't react fast enough to his dilemma. He claims promises to fix the rundown stadium were repeatedly broken. So Modell turned to Baltimore, a town that ironically lost its beloved Colts to Indianapolis in 1984. Maryland offered Model a $200 million deal that included a new stadium with lots of sky boxes, a $75 million moving fee, millions more from seat licenses, concessions, and parking, even a big chunk of revenue from non-football events. Cleveland's counter-offer of $175 million to refurbish the old stadium would have been a nearly complete reconstruction as depicted by this computer animation, but Modell's lawyer told the NewsHour it was too late and claimed it was financially questionable. Modell isn't the only NFL owner to see financially greener pastures. Just this past year, the Los Angeles Rams moved to St. Louis, replacing the St. Louis Cardinals, who had moved to Phoenix in 1988. The Oakland Raiders moved to Los Angeles in 1982 and then moved back this year. Next season, the Houston Oilers will be playing in Nashville. Five other teams are said to be considering moving too. But Mayor White said Cleveland is not going to let its team go without a fight.

MAYOR MICHAEL WHITE: See, everybody expected us to kind of look down at the ground, take our broken teeth out, get 'em repaired, and stick our tail between our legs and go home and say, well, it's Cleveland, what do you expect? We didn't do that. This community stood up on its haunches and said, we're mad as hell, we're not going to take it.

MR. BEARDEN: The city has filed suit against Modell, claiming his stadium lease requires the team to play in Cleveland until 1998. The city has also launched a massive public relations campaign. This sign across from City Hall flashes, "Stop Art Modell," 24 hours a day. Poster-size petitions are everywhere in the city--fast food restaurants, public buildings. A chain of photo shops puts baby pictures on fliers, "Babies Against the Browns' Exit." Apet store has a similar campaign for dogs. People can even sign petitions to keep the Browns in Cleveland on the Internet. Gary Christopher is in charge of the campaign's electronic side.

GARY CHRISTOPHER, "Save Our Browns": You know, we have the dog center field, but now we've got the dogs in cyberspace.

MR. BEARDEN: The Internet connection also allows Browns' fans to get support from and coordinate with other cities facing a team loss.

GARY CHRISTOPHER: We are supplying information for Houston, Tampa, and other areas where they're in the same dilemma, so we're helping those cities too.

BOB GRACE: I think that in the long run, whatever we do here will stop this from happening or slow down this process from happening in another city.

MR. BEARDEN: Cleveland hopes the petitions will persuade the NFL owners, who must approve all moves, to reject Modell's plan. That might be a tough sell. NFL owners originally vetoed the Oakland Raiders' first move to Los Angeles. They were sued by Raiders owner Al Davis and were forced to pay him $50 million in damages. The "Browns Backers" are counting on pressure from Congress to help persuade the owners to take a stand. Mayor White says all these efforts are worth it, not for the sake of sports, but for the sake of the city's economy.

MAYOR MICHAEL WHITE: The best thing we can do is to create full employment for the people living in the cities, and you're not going to do that with social welfare programs, so for me, I see our economic development projects, and that's what the Browns situation is, is a part of a much larger issue of employing our citizens in a variety of ways.

MR. BEARDEN: There has been little local criticism of Cleveland's counter-offer. A tax measure to pay for it passed by a landslide. Not so in Maryland, where the $200 million it would take to build a new stadium for the Browns is being questioned by more and more state legislators.

MS. FARNSWORTH: Since Tom Bearden filed that report, yet another team has announced plans to move. The Seattle Seahawks want to become Los Angeles's latest football team. To discuss the recent wave of relocations and the fallout from all of this we're joined from Boston by Robert Kraft, the owner of the New England Patriots, and by NBC broadcaster Bob Costas, who joins us from St. Louis. Thank you both for being with us. Mr. Kraft, we heard about the economic background to the Cleveland Browns situation. Is that true for the other teams that also have expressed a desire to move? Is it basically the same factors that are causing the moves?

ROBERT KRAFT, New England Patriots: [Boston] Well, I, I think each community has a unique set of circumstances, but the economics of the NFL the way it exists now with the revenue sharing plan we have with our players, the top teams' revenues skew what we have to pay the players. We pay 63 percent of gross, so those teams that don't have good revenue flows from their stadiums are not going to be able to compete long-term in the new NFL.

MS. FARNSWORTH: Do you think generally that franchise stability is a good thing? Is it something that should be promoted and desired?

MR. KRAFT: You know, there's no doubt in my mind, I had the privilege of buying this team in New England two years ago, and the fans have come out in great form. We've sold out every game, and I now realize that I'm really a custodian of a public asset. I think that these teams belong to the communities they've been in for so long, and that it's unfortunate if the fans who have supported team, and Cleveland is the perfect example, get caught in battles between politicians and owners. I believe that what we're about as a product is bigger than those petty fights.

MS. FARNSWORTH: Bob Costas, what about the other moves? Do you know anything about those moves that makes them different from the Cleveland situation? BOB COSTAS, NBC: [St. Louis] I--

MS. FARNSWORTH: It's pretty much the same deal?

MR. COSTAS: I think they're all the same deal. It's only a matter of degree. The Cleveland situation is the one that has drawn the most national attention because it's the most outrageous. The Browns are one of the most traditional franchises in all of sports, a team identified not just with their city but with the entire history of the league, a national franchise in a sense, in terms of being one of the signature teams of the NFL, and as your report indicated, they've had almost unparalleled support. So leaving aside the merits of Art Modell's argument, assuming there are any or Ken Baring's in Seattle or Bud Adam's in Nashville, or Houston to Nashville, what fans everywhere are now saying is wait a minute, if this can happen with these teams, especially the Cleveland Browns, is any city safe? Is any franchise safe? And what's the meaning of an attachment to a team? If I'm City B and the team has abandoned city A, despite rabid fan support that they've had in Seattle for example, or in Cleveland, now they come to my city, what kind of fools arrangement is this where I say, ah, it's my team, I'll love this team, I'll be devoted to this team, I'll pass that allegiance on to my children? Eventually, if this keeps up, it's not just going to affect the city specifically involved in the franchise transfers, it'll affect the credibility of the entire league because fans everywhere will begin to wonder just how truthful is this supposed arrangement between a team which appropriates the name of the city and wears colors to represent that city and the fans who support it but then eventually run the risk of being abandoned?

MS. FARNSWORTH: Well, and Bob Costas, what about a solution which has been suggested, that the team would move to Baltimore but the name and the uniform would stay and another team would come and be the Cleveland Browns, what do you think about that solution?

MR. COSTAS: Well, regardless of the other reason for which he might be fairly criticized, Ken Baring in Seattle, attempting to move his team to Southern California has said I'll leave the name Seahawks and I'll leave the Seahawks colors behind and, in effect, start a new history in Southern California. While it would be preferable for the Browns not to leave Cleveland at all, one possible compromise making the best of a bad situation is just what you suggest, Elizabeth, that maybe they should go to Baltimore and become the Baltimore Crab Cakes or the Baltimore Modells or whatever, and leave the name Browns and the team colors and even the team records behind. Let someone wearing the uniform of the Cleveland Browns try to break Jimmy Brown's records or Brian Sipe's passing records or whatever the case may be, and let Art Modell start, in effect, a new franchise, with a new history from day one in Baltimore, if he can't be stopped from moving there in the first place.

MS. FARNSWORTH: Mr. Kraft, what do you think about that?

MR. KRAFT: Well, I think Bob is right on, that the fans support- -we have to be careful not to abuse the fans' support that we've been giving. Their the ones watching on TV, buying the paraphernalia, and in the end, we've built a trust with them, and if we start pushing themaround, then I believe it'll hurt the overall product and the strength of the NFL. Think about it. A hundred and thirty-eight million people on Super Bowl Sunday watched our product. We have to hold that trust very dearly, and do everything we can to solidify the franchises staying in their hometowns.

MS. FARNSWORTH: But, Mr. Kraft, you would not--you wouldn't support something which would make it impossible for teams to move? You think they should be able to move sometimes, don't you?

MR. KRAFT: Well, under certain circumstances I don't believe a community gets the benefit of a team unless it's competitive, the economic benefits that Mayor White spoke about, and if, if--they're in a bad situation where they don't get fan support, or they can't get the infrastructure support to build a new venue, then they should be free to move in a limited area. The problem we have right now is that the owners have been suing each other ever since this Al Davis move.

MS. FARNSWORTH: You're talking about the Raiders' move to LA from Oakland?

MR. KRAFT: Right. And I think if we could get some kind of limited anti-trust exemption, that that would do a lot for those owners who want to see stability. I'm a new owner who paid a very high price two years ago. I think it's good business that the team stay in the markets they're in, and we not have free agency in franchises.

MS. FARNSWORTH: Can you explain how getting the limited anti- trust exemption would help you?

MR. KRAFT: Well, my understanding of that is that would prevent- -that would allow us to have a set of rules that we could follow without having our partners sue us if we tried to block them from getting another better economic deal. See, I don't think anyone should come into this business who's driven by dollars and cents because there are a lot easier ways to make money and they really have to look at themselves as custodians of public assets.

MS. FARNSWORTH: Okay. Because this Cleveland-Baltimore deal has generated so much interest, and there's been so much news about what Baltimore offered, I want to talk about that with you, Mr. Kraft, for a minute, and also with Mr. Costas, what is the benefit of a team? There seems to be a big debate over this? How much economic benefit really accrues to a city from an NFL team?

MR. KRAFT: Well, our analysis shows that we bring directly between--we have an income tax here in Massachusetts, if you don't know, close to 7 percent. So our payroll between the stadium and the team is $60 million, is $4 million direct state income tax, but overall, we feel we bring $20 million in direct taxes and on a ripple effect probably closer to $40 to $50 million. So that by itself would support some kind of public support of infrastructure, not to lose that revenue base.

MS. FARNSWORTH: And Bob Costas, what is your understanding of how much money a team brings in? You know this better than I, but there is so much debate about it, and I've seen the economists who say that a team brings little more benefit than a Wal-mart.

MR. COSTAS: Well, I may know it a little bit better than you, Elizabeth. I don't know it as well as some economists do. I have seen various reports, you perhaps have seen them too, where economists say that the benefit is overstated because the entertainment dollars specifically are not additional dollars brought to a community by a sports team but simply dollars that would be spent someplace else, at the movies, at a restaurant, at an amusement park. Now, I know that interpretation is subject to debate, but that thought is out there.I think the benefit varies from community to community. The concept of giving businesses a break in order to attract new revenues or bring or keep jobs in the community, that concept exists outside of sports, cities bid for conventions, they bid to bring industries and factories into, into their communities, so there's nothing wrong with that in theory, but it's a matter of priorities. Should a city, which may have trouble with its police department being under-funded, or its roads need repairs or its school system is in need of upgrading, should that city bid as avidly as some cities have to enrich already wealthy players and owners at the expense of other city priorities? It isn't that there isn't a benefit to having a team, but where does it fit when we prioritize things?

MS. FARNSWORTH: Mr. Kraft, how would you answer that? You want Boston to build a new stadium, right?

MR. KRAFT: Well, no, let me clarify that. I think Bob hit it well, especially in the older Northeastern cities, there are a lot of priorities in the school systems, welfare, and a number of other areas. We have a plan for a privately-financed stadium up here, and we're looking for government support in terms of infrastructure and in terms of transportation, and roadways and other things. Similar to what it's done to bring other businesses there. But I believe there's a certain psychic benefit of a team when it does well in a community that can't be duplicated anywhere else. In this town, I know in '75, when they had the bussing problems, and the Red Sox were in a pennant drive, it did more than anything else that helped to cool down feelings in this city. That was told to me by the publisher of the "Boston Globe."

MR. COSTAS: I think what Bob says is correct, Elizabeth. Again, keeping it in perspective, and within reason, a sports team can be somebody important to a city's identity. Ironically, the Cleveland Indians, along with other developments, the Rock'N Roll Hall of Fame included, raised people's consciousness about Cleveland outside the city. It changed the city's whole sense of itself, the way the Indians performed this year, got to the World Series, brand new ball park, so there's no denying that it can be a plus. The question is: How far do you want to go, especially when it approaches an extortion game, in order to raise people's spirits?

MS. FARNSWORTH: And finally, Bob Costas, on all the--I want to talk about the lawsuits briefly. There's a whole series of lawsuits. Cleveland's filed a lawsuit against the NFL and against- -and Baltimore has filed a lawsuit or Maryland has. What kind of effect is that having on the NFL and on football?

MR. COSTAS: Well, it's having a chilling effect on the League's ability to regulate these franchise moves, because in antitrust cases, you're looking at treble damages if you lose, and that's why Commissioner Tagliba has gone before Congress and asked for a limited anti-trust exemption, which would allow the League to write rules that would still permit some franchise shifts in specific situations but the rules supposedly would be reasonable and they would be enforced in an even-handed way, and if the team didn't qualify under those League rules, as a member of the League, as part of the partnership, they could be turned down. I think Commissioner Tagliba was correct when he says the enterprise is the League itself. When each of these franchises begin to operate in maverick fashion, it weakens everything that has allowed the League to flourish, and by extension has allowed the players too to flourish with all the income that they share in.

MS. FARNSWORTH: Mr. Kraft, we just have a few seconds left. Do yo have any sense of how the vote will go tomorrow on the move to Baltimore?

MR. KRAFT: Well, I have a feeling, given what Bob has described so well, that we have a need to solve the problems of both Baltimore and Cleveland and I hope we can start to attract owners that don't believe you do business by suing one another and get ourselves out of the court.

MS. FARNSWORTH: Okay. Thank you both for being with us.

MR. KRAFT: Thank you, Elizabeth.

MR. COSTAS: Thank you, Elizabeth. SERIES - ON THE STUMP

MR. LEHRER: Now, the last in our series of stump speeches by the Republican Presidential candidates. Tonight, businessman Morry Taylor. He spoke last week to the Rotary Club in Carroll, Iowa.

MORRY TAYLOR, Republican Presidential Candidate: [Carroll, Iowa, January 29] All the men that are running are very fine, fine men. And if they were here, they would speak to you, and they would tell you of the vision that they have. They would tell you that big government is too big, they would tell you it's got to be shrunk, and more's got to come back to you, your taxes are too high, and they'll go on and on and on. And I think it's all nice. There's only one thing that none of them will ever tell you, exactly how they're going to go about it. And you see the fiasco in Washington. Well, I come from a different perspective from them. I, I come from the side that's going to tell you right up front what you have to do if you want it fixed. There's only one way to do it. You have to step up, you have to take one third of the bureaucrats starting at $143,000, down to $50,000, and you got to take 'em out. Now, for the shock of anyone, that's one million federal workers taking out of that range. And trust me they would not--you would never notice it either. In fact, the only way you would notice it is things will get better. And if you think about it, you think about November when the President, the great Democrat, he laid off 800,000 and it really didn't affect a lot of people, but the 800,000 he laid off a lot of them were the park rangers and as they called them, non- essential, but that still left 2.2 million left. The difference between my style and their style is No. 1, I take 'em off at the top. I don't touch the bottom. Never have in any of my business acquisitions, never have I cut any hourly worker, not so at the top. I've always started at the top. And what does that get you? That saves you $65 billion now. You pick up $130 billion in administrative. That's $195 billion. That gives you a budget surplus of $30 billion, and you haven't cut a program. Now, are there a lot of things to cut? Sure. But then you have to turn around and you have to have Congress's approval for that, and that's where you're going to get your tax, to get more to you and less to them, and that's the first thing. The second thing, and for you who worry about the million that just got the place, I told you that it was $30 million in savings. I'll take--$30 billion--I'll take $25 billion of it, and I'll send 'em home and I'll send 'em $25,000 a year until we can get 'em jobs. And how are we going to get 'em jobs? Of all the candidates running and all the talk, there's only one who's ever created jobs, good manufacturing jobs, and you got to have jobs that are going to pay 10 to $20 an hour, and we have to boom this economy, or you're not going to get out of it. We have to get smart and get tough, and then once you've done that, you turn around and you come in with afair, simple tax code. The flat tax that everybody's talking about, well, I don't know how many of you in this room are debt-free and got a lot of millions, because if you are, it's a great plan. Under Forbes's plan I make out like a big bandino. I won't have to pay any tax. I sold $15 million in stock to get into this thing, and I paid about $5 million in tax. Under Forbes's plan, I wouldn't pay a penny. He exempts way on the bottom and he exempts at the top. You don't have to be a rocket scientist to figure out what's going to happen to you. It'll just be bid right up. You got to do something everybody looks at in this country that's fair-- zero to $20,000, 2 percent--that's 400 bucks on 20 grand. Let everybody pay. If they're on welfare, give 'em the 2 percent on January 1st, but they got to pay it the same as we take it from people to help them. Every thousand dollars you make over twenty grand up to thirty-five, each thousand above it, we take 10 percent. But once you get to $35,000, 17, which is a max, so all of those who pay capital gains and everything else, wherever you fall in that range is where it'll be, so capital gains really gets reduced from 28 down to 17. One deduction. That one deduction will be for your, your home mortgage interest, and if you're a renter we'll give you 10 percent of your rent up to a max of $2500. I'd like to caution you all since I got into this thing and got to know everybody that's in it, it almost makes it scary. And the only thing that you can turn around and tell people is you tell 'em this: You're all intelligent, this country is in trouble, and a lot of other people are going to suffer, and everybody better wake up and see exactly what's going on. And talk is cheap. I've been a doer most of my life. My nickname is the "Griz." And I got that from Wall Street, a little old country boy like myself, and the reason they gave me that nickname is one guy stood up and said, "Like the American Grizzly Bear, he wears--Taylor wears no man's collar." I put my own cash up to give you a choice, and I don't want a salary, so you give half to the Boy Scouts, half to the Girl Scouts, no pension for the presidency. You shouldn't be paying Congressmen pensions or you shouldn't be paying Senators pensions. Have you ever seen a shortage, ever a shortage running for office? It's not like no one wanted the job. I am different, and I only promise you one thing, and i don't promise things--I'm not all the other candidates, if they're here, they want you to love 'em, I only want my life to love me. I don't want you to love me. The only thing I want is that if I was elected to go do the job, and I look at the presidency as a job, is that if I go do the job and I get it done, I've earned your respect, because that's all I say and the same of my business. I don't look for employees to love me, but I sure in the heck want their respect, that I do what I say I'm going to do, so I'll balance that budget, put the management there, and I will boom this economy with jobs, good paying jobs.

MR. LEHRER: Republican Presidential Candidate Morry Taylor speaking to the Rotary Club in Carroll, Iowa. ESSAY - WHO DONE IT?

MR. LEHRER: Finally tonight, essayist Roger Rosenblatt wonders, where have all the good mysteries gone?

ROGER ROSENBLATT: The usual suspect is a terrific throwback to the kind of movie you don't see a lot of these days. It's a mystery, a great, old-fashioned mystery, complete with a criminal mastermind, a number of deliberately diversionary devices, some obscure but logical clues, and it is fired by thebest of questions: Who done it? Most movies made nowadays are thrillers, not mysteries. It makes you wonder why. Are we tired of discovering who done it? Do we no longer care? Would we rather see a shoot 'em up or to be more accurate an explode 'em up than a story of cleverness and intrigue that makes us want to work through a puzzle? Not that the new thrillers aren't fun to watch. Many decent-minded people would not go near one, but my low-minded friends and I dearly love to head for the theater, preferably for the last of the late shows, and hunker down in the fourth or fifth row to watch Steven Seagal, Sylvester Stallone, or Arnold Schwarzenegger beat up or blow up much of the world. It is very relaxing.

ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER: [in "True Lies" segment] Do you tango?

ROGER ROSENBLATT: The movie "True Lies" begins natty in a tax, waltzing into a lavish party to which he was not invited, then tangoing with a beautiful villainess and finally, as he fox trots away after a Halcyon evening, blowing the place sky high. [explosion] Typical behavior for today's thrillers, almost boring really. All you have to do is see Steven Seagal walk into a bar filled with unshaven characters and you know at once, there goes the neighborhood. Compare all this mayhem to the "Mask of Dimitrios," the grand old mystery film to which the usual suspect has a pleasant resemblance, or those wonderful mysteries made between the 1930s and the early 1970s, "The Kennel Murder Case."

WOMAN: I think he's dead.

ROGER ROSENBLATT: "Stage Fright."

WOMAN: I didn't mean it.

ROGER ROSENBLATT: "Bullitt." "To Rage."

ACTRESS: She didn't do it.

ACTOR: Oh, she did it all right.

ACTOR: Can I ask you some questions?

ROGER ROSENBLATT: "Klute," splendid pictures all. The idea behind such films was that the audience wanted to be titillated, indeed, thrilled with a problem that needed solving, that everyone was deep in hers or her problem-solving heart a Sherlock Holmes. Thus, the popular Sherlock Holmes series of movies in the 1940's with Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce.

SHERLOCK HOLMES: My conjecture is that he'll be murdered.

ACTOR: Murdered?

ROGER ROSENBLATT: Few of those films were true whodunits, since the audience knew it was usually Professor Moriarity, but they were mysteries in the sense of urging us to follow a mind on a trail.

ACTOR: A medium dry martini, lemon peel, shaken, not stirred.

OTHER ACTOR: Vodka?

ACTOR: Of course.

ROGER ROSENBLATT: It may have been the James Bond series that eventually drove our mystery movies away. Audiences may have decided that it was more entertaining to see a hero destroy than seek, or maybe that mysteries, themselves, were no longer interesting. Thrillers are more like microwaves or minute rice; they're quicker; they cut to the chase, rather than chase. Maybe people decided that in an unjust world justice was more efficiently served by a Rambo armed to the teeth, shooting everyone in sight, than by a William Powell or a Dick Powell or a Humphrey Bogart or an Alan Ladd, doggedly progressing from clue to clue. But "The Usual Suspects" is a reminder of how gratifying it can be to sit in the dark and wonder how things will turn out.

ACTOR: If I see you or any of your friends before then, Ms. Finneran will find herself the victim of a most gruesome violation before she dies, as, indeed, will your father, Mr. Hockney. If you'll excuse me, gentlemen.

ROGER ROSENBLATT: We have evolved in this past century from "who done it" to "done it." Still, there is nothing like that wondering. What I miss most in moviesis the final wrap-up scene: Charlie Chan naming the murderer as the lights go out, or Sam Spade giving up the murderess he loves, or the Saint or the Falcon, or Nick Charles.

ACTOR: A murderer is right in this room, sitting at this table. You may serve the fish.

ROGER ROSENBLATT: Was there ever a better wrap-up than the final dinner scene in "The Thin Man," in which suspect after suspect is eliminated until we come down to the one most unlikely suspect, who done it? Picture Steven Seagal walking in on that dinner. First he says, "Okay. One of you is guilty." Then he blows up the room. [explosion] Gotcha! I'm Roger Rosenblatt. RECAP

MR. LEHRER: Again, the major stories of this Thursday, President Clinton signed the Telecommunications Bill into law. The ACLU immediately filed suit to block one part of it. House Speaker Gingrich said he was optimistic there could be a balanced budget deal next month, and the worst flooding in more than thirty years killed two and forced thousands from their homes in Oregon. We'll see you tomorrow night with Shields & Gigot and a second look at the Vermeer exhibit, among other things. I'm Jim Lehrer. Thank you and good night.

- Series

- The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer

- Producing Organization

- NewsHour Productions

- Contributing Organization

- NewsHour Productions (Washington, District of Columbia)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip/507-0r9m32nr1t

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip/507-0r9m32nr1t).

- Description

- Episode Description

- This episode's headline: Unplugged; Turf Wars; On the Stump; Who Done It?. ANCHOR: JIM LEHRER; GUESTS: REED HUNDT, Chairman, FCC; ROBERT KRAFT, New England Patriots; BOB COSTAS, NBC; MORRY TAYLOR, Republican Presidential Candidate; CORRESPONDENTS: MARGARET WARNER; TOM BEARDEN; ELIZABETH FARNSWORTH; ROGER ROSENBLATT

- Date

- 1996-02-08

- Asset type

- Episode

- Topics

- Social Issues

- Literature

- Technology

- Film and Television

- Energy

- Employment

- Politics and Government

- Rights

- Copyright NewsHour Productions, LLC. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode)

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:58:59

- Credits

-

-

Producing Organization: NewsHour Productions

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

NewsHour Productions

Identifier: NH-5459 (NH Show Code)

Format: Betacam

Generation: Preservation

Duration: 01:00:00;00

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer,” 1996-02-08, NewsHour Productions, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed December 20, 2025, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-507-0r9m32nr1t.

- MLA: “The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer.” 1996-02-08. NewsHour Productions, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. December 20, 2025. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-507-0r9m32nr1t>.

- APA: The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer. Boston, MA: NewsHour Productions, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-507-0r9m32nr1t