Bill Moyers Journal; 308; A Conversation with Archibald MacLeish

- Transcript

. . . . . . . .

. I believe the Republic exists, I believe with all my heart it exists. I believe it's alive, creative, doing well. But I'm afraid that unless we give more thought to it to its possibilities, to what it gives us besides the wages we have and the satisfaction of various kinds we have, what it gives us in terms of human relationships, in terms of humanity, our basic humanity, unless we become again the essentially humane people that we were known to be the whole world for about a hundred years. We may find ourselves with nothing but our possessions left. How do you think, therefore, we should celebrate the Byzantine?

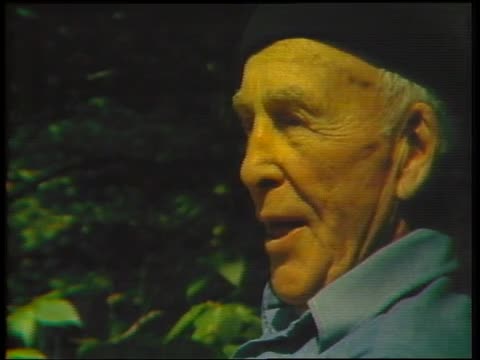

You know how John Adams wanted to celebrate it? He named all the possible means of making noise in the world. He said that what you had to do on the fourth day of July was to get out and parade and shoot guns and light bonfires and dance and make speeches, and just a great volume of glorious noise. Well, of course the trouble with the Byzantine year is that we're going to have that for 12 months. No, I think a humble sense of gratitude to whoever God is and wherever He is for the opportunity of self-government, my God, what a privilege that is if we can exercise it. This is Archibald McLeish at 83. I'll be talking with him about his life and work and about the American experience.

I'm Bill Moyers. This scene here, for example, is a wonderful web of little New England rivers. Down in this valley is the south river which goes through this town. Then next going down in the gorge that goes that way is the Bear River, which is the north end of town. Then is the deer field, which is a lovely river, a real river, which flows into the Connecticut. And in that far valley, the side of the Ray Hill is the Connecticut. Which is one of the great rivers in the world.

Wonderful name, Bear, deer field. Oh, yes, deer field in the Connecticut. Why do you like it so much here? Silence. Silence, which is the rarest thing in the world now. But what you can be sure of here, I work in that stone house over there through the tree, beyond the tree, and I can dig in there. I know that even if they call me from the house, I don't have to hear them. And I'm sure I'm safe from sort of events down below. Nothing's gonna happen. Occasionally motorcar will go by. What was here when you came? And did you, you and Mrs. McLean do what we see here? I'll have to show you a picture of what was here. This place had been bought by somebody from the south who had covered it with pillars and columns and porches. And we had to strip all that off partly because it was rotting away and partly because it didn't belong with the house and get it down to that beautiful square, simple, clean shape. And once that was done, we just lost our hearts to it.

In fact, it's like a person to us. We have so deep a sense that it's there and that it's aware of us if that doesn't sound too silly. You know, it seems to respond to our being there, being around. How about the garden? Did you do that? No, well, it's Ades. Ades designed. This was, there had been a barn on this part of it. It was covered with loose stuff under the ground rocks. I mean, and all those rocks are in dry walls. That's a dry wall. There's a dry wall there, dry wall there. So it makes an... This side is cemented because we have earth to get above it. Do you like to work with your hands? I love it. It's the great... It's the great instigator of the mind because you can... You're working with your hands and you don't think you're thinking, but you are. And you surprise yourself when that happens. You were how old when you came here.

1927. I was 7 plus 8. I was 34. Do you remember that poem you wrote at 20? Stooped round about. I thought the world a miserable place. Truth, a trick, faith in doubt. Little beauty, less grace. I remember that. Yeah, and it goes on. Now at 60, what I see all over the world is worse by far. It stops my heart with ecstasy. God, the wonders that there are. At 60, I thought, you know, I'd plumb the depths of old rage. I hadn't even begun to look at it. You wrote that at 60. Well, I take it, I did, because I said at 60 in the poem. Well, what's changed between 60 and 83? Oh, you're... You're a whole feeling about yourself. The things that you've gotten past and have regretted as you had passed them, but have now learned to get along without the things

that drop out of your life. It's an extraordinary sense of freedom. In my case, freedom plus a wonderful and complete companionship, which is necessary to that sense of isolation and freedom, because otherwise it would be isolation and loneliness. All that happens. I found the decade of the 70s. A really wonderful country. You're going to like it, Bill, when you get there. The 70s. I hope I travel it. I'll report you on the 80s later on. All right, I'll come back. Come back 10 years from now. I'll let you know. Although we graduated from Harvard Law School at the head of his class, Archibald McLeish gave up the practice of law half a century ago, because he felt compelled to write poetry. SUNY was one of America's most distinguished artists of language. His honors are too lengthy to list, but they include three Pulitzer prizes, including one for his verse played JB, based on the Old Testament story of Job. Under President Roosevelt and Truman,

he has held several government posts, Library of Congress, a director of the Office of War Information, Assistant Secretary of State, and a founder of the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. He is lectured and taught around the world, but he belongs here, he says, on his farm in Western Massachusetts, where he does most of his writing. Poet, playwright, teacher, and public official, he has been a long and successful career, but his enduring passions have been for Ada, his wife, Portray, and the American Republic. Do you know why he became a poet? No. If I knew the answer to that question, I'd be infinitely wiser than I am. I was perfectly happy practicing law. The practice of law is the greatest indoor game in the world, just like pocket billiards. And it's great fun, and if you're good at it, and I was fairly good at it, it's very rewarding.

Also, it makes a lot of money. But there was this other thing I had to do, and why Bill, I couldn't tell you if you trusted my arm. Well, without twisting your arm, was there a moment when you realized, without understanding why, when you realized you had to do it? Yes, yes, yes. Well, there was a moment when I realized that, that I had to leave the law. This is as clear in my mind as, how long ago is it now, 60 years? It's as clear in my mind as though it happened last night. The office that I was in, if you know Boston, was on State Street, back at the Old State House. I used to walk over to Park Street and undertake the subway back out to Cambridge, and walk out home. And I started on a late winter night, very clear night, very cold, with a moon in the west, which I can see now. This nagging thing was in the back of my mind. By the time I got to Park Street under,

I went right by the subway entrance, and walked the length of Commonwealth to Massachusetts Avenue, and the length of Massachusetts Avenue to Harvard Square on another mile home. I don't know how long that walk is, but it took me quite a while. And I simply pounded it out with myself, and came to the conclusion that if I was ever going to do the thing that I felt in my heart, I had to do it, I would have to make the decision then, that night, that great night. I got home, found a day to worry to death, and mad. We sat up all night and talked about it, and we decided we'd do it. And you went to Paris. And about four or five months afterwards, and stayed there for about six years. Not for the reasons, which sometimes seem relevant. That is to be part of a group of ex-patriate Americans. This is the biggest piece of nonsense

ever perpetrated. We went to Paris, one, my wife is a singer, was, she would say, who had spent a good deal of time working in Paris. She knew the city, I know it. We both wanted to live there, and there was a marvelous inflation going in Paris, which made it a very much cheaper place to live than Boston, so that we weren't able to live there. That's why we went. And then later on, we had the enormous dividend of being part of that extraordinary gathering of the young from all over the world, who crowded into Paris in the decade of the 20s, because because I was there, because Stravinsky was there, because they ceased were writing, because my son started, because, you know, it's just endless richly Americans, himingway, and himingway, Scott, Dawson, many another. Do you remember those days clearly now? The Paris days I couldn't possibly forget.

That city, as itself, enters your memory and sits there, and you can't get away from it. The smell of the carpeting made, I think, a sort of cook all matting that was used in inexpensive apartments. I can smell that. We lived in so many of them. I can smell that. I might sleep and awake. The beauty of the city. The loveliness, that gray pearl light that Paris has, the water cards early in the morning. And the possibility of work. The whole city was working. They left you alone. You were part of the flow of it. Someone told me that the fall of France in 1940 had shaken you profoundly. Is that true? Well, it was a crushing blow. I saw it as the fall of Paris. And it seemed to me that Paris had become in the six or seven years that we were there. I mean, it became during that period.

Not only the center of the creative and artistic life of the world, but a sort of representation of it. Wherever you went, there were indications of it. There were things going on. There was a sort of new beginning of the spirit of man. And it was expressing itself in the arts. And the occupation of Paris seemed to me to be particularly by the people who did occupy it. And for the purpose, for which they occupied it, seemed to me to be an unbearable indecency. The twentieth century has been filled with unbearable decencies. And most people aren't poets and cannot see the loveliness beyond the horror. And I often wonder whether poetry isn't a way out for the poets that somehow just doesn't justify,

but it somehow makes tolerable the unbearable decencies that ordinary people are left to deal with. Bill, I would take that and set it in quotation marks if you would change one word. Not a way out, but a way in. Poetry is a means of knowing. It's a means of knowing the kind of thing that can only be known emotionally. And it can't be analyzed, taken apart, spelled out, put back together again. Poetry takes the apple hole, eats the whole apple. Doesn't chew it up and then adjust it. It is capable of that kind of truth of perception. And it is capable of perceiving the tragedy of life, as Shakespeare, I must say, demonstrated in many before him, it's capable of seeing the tragedy of life

as nothing else can see it. The great reaches of the Bible, which penetrate the tragedy of life are largely like Job poems, like the Book of Job. It is a means of knowing. And its great triumph is that when it succeeds, which it does much less often than it thinks or anybody else thinks. But when it succeeds, it makes the unbearable, bearable because one can see what it is. At last, one feels it. Wordsworth said, truth carried alive into the heart by passion. That's what poetry was towards word. Truth carried alive into the heart by passion. Well, the truth of tragedy also carried alive into the heart by passion. That also becomes comprehensible. Would that be the answer to your own question? The one you raised in a poem you dedicated to Wallace Stephen when you asked, why be poet now?

When the meanings do not mean. Why be poet? Exactly. I'm glad you read that. That's true. That's it. What is this though for that? Why should those of us who are not poet read poetry? People read poetry. I think for the same reason really that poetry is written, but in reverse, you write a poem in my experience. I wouldn't expect to have any agreement about this, but you write a poem in my experience because as a sculptor, it gets hold of a piece of marble, which he can see has got a girl in it somewhere. He can get that out. He's going to get that kneeling girl. You run into a piece of experience, which you know contains something that is going to be a poem. You don't know why exactly, but you begin to get a feeling of it. And the work of writing, which is very rarely

that surge of inspiration, which is supposed to take place, but which is usually very long, very laborious and extremely painful, is the work of trying to find a poem within the experience. Now, I think the reader comes at the same thing in reverse. What he's faced with is the poem. It's a combination of sounds, rhythms, images, it's a whole, it's almost an object. What did it come out of? And what does it really contain? And this experience can be, whereas the creation of the thing, they have been laborious and painful. This other experience, though it can also be laborious and painful, is enormously rewarding if he just happens to have to do with a great poem. I think it's the oldest poem to which we have recorded music

in English. It's in the Bodleian, the manuscript of it. Oh, Western wind, when will thou blow that the small rain down can rain? Christ that my love were in my arms and die in my bed again. Now, this is very simple, very clear, little scene, some very simple observations about weather, but it's also a great deal more than that. It almost, almost, for the reader who is sensitive enough, catches a bit of the experience of love. It's in there. It's in there. It's always in there for me. I've always moved me when I come back to it. That's one of the reasons that the poetry poetry has always rang with such affirmation. Somebody even said you still look on the world with ecstasy.

And that I remember one of the characters in JB, the child, Jolly Adams. Yeah. She's told to look away from Job with all his sores for fear that the ugliness will stay with her, that she'll remember the agony. All the sores I've seen, I remember. Do you remember the afflictions of this 83-year life that's been lived through war and disease and plagues and corruption? And one can't forget them and they are continuous and they search you out if you try to forget them. But I suppose the real question is not whether they are present in your mind, but whether with them present in your mind are the things that don't counterbalance them

because they're in a different sort of balance altogether. But give even them meaning that the quality of life to which one can really apply the word humanity, the humanity of so many lives that one sees lived around one, which in a sense put the miseries and sorrows in their place because these people one sees and one admires have of course all had their own sufferings and their own sorrows. The delight of life is so much greater than the sorrow of it because the sorrow does eventually become part of the delight. It's a deep enrichment. I suppose this really means

that I've been extraordinarily fortunate in my life. I have the kind of marriage about which you can't say anything. It's just a wonderful marriage. It's existed for about 60 years. It'll go on as long as we're around. As long as there is us to be married and perhaps even after that. What are the thoughts of a man who's lived 83 years about his life in times? Thoughts he hasn't expressed before? Well, you... At 83, you're views of not of your life in time but of yourself in your life in time, which is really the turning point. Begin to change quite a lot. You become remarkably

less afraid of death. If you ever were, I'd never been much afraid of death. I have no anchoring for dying. That's something I'd like to get by easily as possible. The Irish talk about a happy death. If there's any Irishman around who'd like to tell me how to do that, I'd be pleased. But I'd never been much afraid of death. But now I have a very easy feeling about it indeed. My only feeling about death now is that I'm not if possible to arrange it so that I won't cause pain to somebody I care a great, great deal about. I have a point about that incidentally. It tries to get at it. The recent point? The recent point? I've just finished a group of about thirty poems, most of which, two thirds of which,

at least, haven't been published. I'm going to bring them up next year. Autobiographical. They are quite so, I think. Actually, some of them are poems that have been batting around in notebooks for a while. And I finally came to grips with this summer. I've had a very good summer of writing, very good. Good productive summer, they say. Some of them are just appeared out of nowhere this summer. So they cover a certain period of time. The one I was talking about that is the one that I said. I had written a poem on the theme that you had mentioned is this one. It's called the Old Grey Couple. There are two.

The Old Grey Couple are placed in the scene and then they have a conversation. And the Old Grey couple goes this way. They have only to look at each other to laugh. No one knows why, not even they. They go back in the lives they live, they both remember. But no words can say. They go off at an evening's end to talk, but they don't. Or to sleep, but they lie awake. Hardly a word, just to touch. Just near. Just listening, but not to hear. Everything they know, they know together. Everything that is but one. They live, they learn like secrets from each other. Death, they think of in the nights alone. And then they get talking. And this is the way that dialogue goes. She.

Love says the poet has no reasons. He, not even after 50 years, he, particularly after 50 years, he, what was it then that lured us, that still teases? She, you used to say, my plated hair. He, and then you'd laugh because it wasn't plated. She, and now it can't be. Just the Old Grey couple. Love has no reasons, so you made one up to laugh at. Now, to prove the adage true, love has no reasons, but old lovers do. She, and they can't tell. He, I can, and so can you. 50 years ago, we drew each other, magnetized, needled, or the longing north. It was your naked presence that so moved me. It was your absolute presence that was love.

She, and now he, years older, I begin to see absence, not presence. What the world would be without your footsteps in the world. The garden empty of the radiance where you are. She, and bats, old lovers, reasoning, they see their love because they know now what its loss would be. Because, like Cleopatra in the play, they know there's nothing left once loves away. Nothing remarkable beneath the visiting moon. There's, is the late last wisdom of the afternoon. They know that love, like light, grows dearer toward the dark. Well, this is called Family Group. I think it completely explains itself. I had a younger brother. A remarkably beautiful young man

who left Yale in the, when the war broke out in 1917. He was in the class of 18. And joined a small group of people who were learning to fly planes for naval aviation. This was the beginning of naval aviation there. We had no naval aviation. And he went to the front head of, he was on the front flying for something like very close to two years, which is about 20 times longer than most people lasted in those days. He was shot down in, you know, on the 14th of October before the armistice. And his body was not found until the middle of the next winter, because he fell in flooded country. And this is a poem called Family Group

and it's imagined as a photograph, two photographs. That's my younger brother with his Navy wings. He's 22 or would be, but for six months flying camels at the front. I'm beside him in my brand new world. The town behind us ought to be limoge. That's what we met by accident that April. Someone's lengthened shadow, the photographers, falls across our feet. This others afterward, after the armistice, I mean the winter floods, the months without a word. That shattered barnyard is in Belgium somewhere. The faceless figure on its back, the helmet buckled, wears what looked like Navy wings. A lengthened shadow falls across the muck about its feet. I'm back in Cambridge,

with clean clothes, a comfortable bed, my wife, my son. Well, what can one say? I don't know. The curious quality of a poem is that it can be far more naked than prose, and if you can tell me why, I'll bless you. I don't know why. You can be, in fact, where besieged these days with a literature that is, as they say, explicit, extremely explicit, nakedness deprived even of its nakedness. But somehow there's nothing embarrassing about it, and yet a poem without being explicit

to all can be much more naked, and there isn't anything to say about things like that. There they are, or they aren't. What's been the agony of Archibald MacLeach behind the poetry? Well, I tried a few minutes ago to talk about the specific events, the Saros, the death of a son, the death of a brother, the miseries of the First World War, all these things, which eventually become part of a pattern, part of a fabric, and therefore part of life, and therefore acceptable. I think the real, or agony is not the wrong word for it.

Now, the real motivating agony with me, if I can talk about a motivating agony, has been the long struggle with the art. When Frost was 80, we gave a dinner for him down here in Amherst, and he was asked to read a few poems, which he did. I was running the dinner, so I suggested to him taking advantage of the chair I sat in. I suggested to him that maybe he'd like to say a word about his poems as separate from himself, and he said, well, he'd do that. What he said was that he had always hoped to write a few poems, which would be hard to get rid of.

Now, that's really it. And the motivating agony in my life has been the constant defeat. I suppose it's the defeat that any artist feels. I don't suppose any artist in any art is ever sure that he has really perpetrated a word of art and may be a fake. This doubt afflicts, I think, any artist. For reasons perhaps having to do with my Scottish and Yankee background, it afflicts me more than most. But the real suffering has been in the work itself, and also, of course, occasionally, real rewards. I may be about to enter a field where the lame shouldn't tread. But I would ask you about what to me seems to be a persistent inquiry on your part, beginning in 1925 with that

in bedeviling work called Nobody Daddy. You have read it. Right on through JB, a great modern profile of Job. In both of them, there is this search for some understanding of our relationship to God. There is this unsatisfied desire to know what has happened between us and God. What you call this vast silence overhead, you've been seeming to reach for, Bill Ladder's toward. I wonder if after 50 years of writing the poetry of the first beginning of the Odyssey to now, do you know any more about the answer? No, I think what I think I know is that the answer is closer to us than it is to the stars,

that the creator of all that out there is not a visible, a mannit manageable entity for us. I don't mean that it's all too mysterious. I mean that it is really too large. I have a young, very brilliant, young physicist friend who tells me that most physicists, I'm his word for it, I don't know anything about this, that most physicists would agree that the direction of evolution in the universe as a whole is constantly towards symmetry. He has reasons for this mathematical reasons which he explains to me, which I don't understand at all. The idea that fascinates me,

but it's also a very, it's an admirable idea that the movement of the universe towards symmetry means that there is a purpose which involves at least one thing that human beings can understand, which is beauty, symmetry, and beauty having much to do with each other. But there is nothing in the idea of symmetry that one would turn with a broken heart. You don't weep on the bosom of symmetry. The real vocabulary, it seems to me in which one can catch the nature of the, I was going to say the thing of Baba, that's such a totally wrong word, but I'm not sure it's a person and the spirit, the entity

that has to do with our lives and the meaning of our lives, that perhaps knows the meaning of our lives, is very much closer to ourselves and that the channel through which, the medium through which is closer to us, is the medium of love. So that I find my way to the teachings of Jesus Christ that way. And to me, the fundamental truth of Jesus is that He does move love into the center of the human experience. And to say that love is the answer to the mystery of the universe is a little bit more childish than I want to be on a program with you. And yet there is something there, there is something there.

Suffering the little children. This piercing of the inner reality within the experience is a very personal way. Does it have any relationship to the larger world, to the political world? You know perfectly well my answer to that is I've never really been able to understand the mentality, which assumes that Horat's poetry works as an instrument of knowledge, an instrument of apprehension in the world of the sexual emotions, for example. It won't work in the world, the political world, the world, the historical world. That's something else. And the poetry should keep out of it and the practitioner of poetry should keep out of it. Well to say this in a time like ours, which is essentially political, is in effect to say

that poetry is a sort of marginal activity, a private activity, which one should reserve for the secrets of one's own life or the private moments that can't otherwise be discussed. And this is just pure nonsense. The reason I say that is because there is demonstrable proof at the very highest level that it's nonsense. The greatest poet since Keats, I think, without any question is William Butler Yates. Yates, down to his 50s, I think early 50s, was an Irish bard writing charming bardic and largely Celtic, at least Gallic, poems and Gallic themes. I don't mean that he wrote them in the Gallic, but he wrote them in English, of course. But in the early 50s, at the period when we're moving in toward 1916, this is about 1914, 1916 is just ahead.

He began to write, as one of his contemporaries in Ireland said, he began to use the English language as though it meant business. And he began to use it about what was happening in Ireland. He wrote poems in that first book of his, the book at that time, called Responsibilities, like romantic Ireland's dead and gone. It's with Olaire in the grave. Well, that's pretty political, and it gets more political as you've drawn with it. And then he gets in eventually to the second coming, which is perhaps the most penetrating statement made by anyone in any form in the last 40 years about the time we're in. Yates became a great poet when he began to treat with all experiences. Experiences of the world is political experience, the agony of Ireland, as well as the agony of Willie Yates. And it's just nonsense to try to, I mean, it reduces poetry to a child's game

if you put a knife through that and say, oh, well, that's for other people. That's for journalists, journalists are out there. We're in here with our hearts, our bleeding hearts, and we're going to talk about our bleeding hearts, well, nonsense. So much of your poetry is consistent with what you've just said as emphasizing the promisey of the individual in our society. And I wonder if there hasn't been a diminution of the individual, as a consequence of these forces, which the founders of the Republic couldn't foresee. Well, isn't the isn't collective action, the action by a society, exactly what the people who wrote the Declaration of Independence and the solid citizens who signed it at the risk of their necks were thinking about? I agree that there's much more we use the word society and we use the word social in a rather different sense. But certainly what the, what the founding fathers

meant by the Republic, what they meant by the people, was the body of the people, the dominant opinion in the country. And the individual, while he was the end and aim of government, it was his freedom that the state existed for. And nevertheless, to bring about these things had to work with others. I want to probe a little bit more of the sense of confidence you feel in the Republic. What worries you right now about the Republic? What are our dangers? It would take some such form as this, the common ground, the common explanation has to do with a lack of concern for the common good,

which means really a lack of sense of the common good, a lack of the sense of a community. The thing that differentiates us from the animals is that we are aware of ourselves and being aware of ourselves we're aware of each other. And being aware of each other we're capable of love for each other, we're capable of strong feeling about each other, like and dislike, but we're above all capable of imagining a community in the sense in which Jefferson imagined a community. And what seems to me to be increasingly lacking, disappearing, fading away, is this commitment to the common life, the sense of being a man and not an individual engaged in aggrandizing his fortunes, or not an individual engaged in fighting off his enemies,

or not an individual who hopes to achieve more power than he now has. The sense of a community, the sense really of the republic, but you do still believe, apparently, that even in a conglomerate age, an age of towering and massive institutions, and an age of technology, the single individual is the essence of what Jefferson meant by this revolution. I do indeed, Bill. I don't really see how the existence of the conglomerate age, the age of conglomerates, of vast international cartels, the age of fewer and fewer corporations controlling more and more of industry, the age of big labor. I don't see how all that can have any effect

but to dramatize the eternal opposition between one man and the material forces against which he has to struggle. The importance of a government, a kind of government, well, let's say a government, dedicated to human freedom, one of the dominant feelings in our time is frequently said to be undoubtedly as the feeling that the human individual is powerless against the organizations of political and economic power. There's very little he can do about it. And that is, I suppose, true. But the same forces that create that kind of situation very shortly create situations in which the enormous importance

of the freedom of the individual becomes clearer and clearer. There are more people suffering from the demands and the exigencies of an economic system made up of huge, giant elements. And they're, I mean, George III, as an enemy, is a piker compared to the things that were up against. Well, that's at the heart of the frustration, it seems to me. How does the individual impinge the poem by forces he cannot even define? Acted a poem by circumstances not of his making. Done too by people he will never meet. How does he react? What does he do? Except where his numbness? I think he reacts precisely by becoming not one consumer or one tin smith or one poet or one whatever. He reacts by becoming a part of a people which is aware of itself

as a people. A people which is aware of itself as a people is not going to be put upon by enemies no matter how huge, how vast they may be. It has very recently as, I think, recent events demonstrated very recently in the case that a sense of the people as a people once re-created, as it was re-created unintentionally by Mr. Nixon's public relations people, will create a power against which conspiracies can't stand. Is this what you have occasionally called the American thing, the American proposition? Is that what you mean by it? What I mean by the American proposition is the proposition that comes out in that great letter

that Jefferson wrote to the people of the city of Washington a few weeks before he died in the summer of 1826. The American proposition, Jefferson was talking to writing to the people of Washington and they'd asked him to come to their celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Republic instead of which he and John Adams were going to die together on that day. He was writing them to say that he couldn't come but that he wanted to write them about what he thought the declaration was and what comes out of it is the statement which I think is what I mean by the American proposition that the right of self-government that is the probability, the likelihood more than possible perhaps not probability but the likelihood that a people can govern themselves is what the American proposition is.

We decided to trust ourselves to govern ourselves. Nobody had done it before. Certainly it never happened in Athens for all the use of the word democracy or the public. Let me read this letter Jefferson is going to say that? Yes, he wrote it in we had 1826. He wrote it in 1826. 50 years after the revolution. And the declaration. And it's really a wonderful document. He begins by referring to the fact that they've been kind enough to ask him to come and there's nothing he'd rather do than meet with those worthy who joined him in Philadelphia but that unfortunately he's ill and there's some things that you can't be a minister of your own soul about and this is one of them. And he says that he or I think I better begin right there. I should indeed with peculiar delight have met an exchange there congratulations personally with the small band, the remnant of that host of worthies who joined with us on that day in the bold and doubtful election we were to make for our country.

Between submission and the sword. And to enjoy it with them the consulatory fact that our fellow citizens after half a century of experience and prosperity continue to approve the choice we made. And then he says this. May it, that is that choice, the declaration. May it be to the world what I believe it will be to some parts sooner to others later but finally to all. The signal of arousing men to burst the chains under which monkish ignorance and superstition had persuaded them to bind themselves and to assume the blessings and security of self-government. If you could ask back to discuss these subjects with one member of the founding era. Who would be your guest? Well, I'd be afraid to take on Tom Jefferson. I think John Adam is probably with whom I would disagree about many things

but about as a fascinating, and lovable man has ever lived nevertheless, and takers though he was. Have you read that correspondence between Adams and Jefferson? Yes, I was provoked to read it paradoxically by your latest radio play, The Great Great Immortality of course. And I went back in my hobby. What impresses you about it? What impresses me about it is the human warmth of John Adams. John Adams wins my heart. Where I disagree with him, I understand entirely why he takes the attitude he does. Jefferson is, with all his intellectual and moral greatness, a little too high and a little too remote. It's hard to get closely in touch with him. Except at moments when, as in the letter of the citizens of Washington, you feel his weakness, his illness, his broaching death, and so forth. And suddenly he comes down to my dimensions.

I can get hold of him. I just want to ask you to read to me read to us these two pages from three pages, let's say, from the Great American Fourth of July parade, which is your latest play about the Fourth of July and celebrating the Basin Tinial. Would you just read me these pages? I would, with great, great pleasure. Adams says, there must be marching on the Fourth of July. There must be ceremony, pomp, parade, sports, games, shows, guns, bonfires, and illuminations. Men must remember this day who they are, or what they are, will leave them. Pride and purpose, must go marching on this day. Well, there's been a Fourth of July celebration, and the master of the celebration is trying to get people to fall in and a parade, and they won't do it. So you hear the bullhorn voice saying, fall in and fall in. And Adams says, tell them, Mr. Jefferson. And Jefferson says,

they would not listen to me if I did. Adams says, the whole great world has listened to you, Mr. Jefferson. Jefferson says, long ago, who listens to a dead man? Adams, the living, when his words still live, you were remembered, Mr. Jefferson. Jefferson remembered, but not believed. Adams, contemptuous voices cheering in the dark, declared the journey of mankind is ended. The truth, they say, is out now. We are naked apes, disgusting animals, ignoble creatures. But when they say this, they remember you, and some few others on the road beside who put their trust where you did in humanity. They ask each other how those victories were won that now, without a gunshot or surrendered, and they think of you. Jefferson, they should be thinking not of me or you or any of us. They should be thinking how their country came to be, what called it, out of nothing in a wilderness. The word that called it,

Adams, the great act of independence. Jefferson, revolution, Mr. Adams. We in our time called it revolution. Now they've forgotten what the revolution was. Adams, our separation from the British crown, Jefferson, much more than that. Much more than that. Read the writ against her. Read the causes which impelled that separation. We spelled them out for all the world to see. They were the causes of all men, mankind, Adams. Those were the reasons afterward, not the causes. Jefferson, reasons that live afterward become the causes. Do not deny your triumph, Mr. Adams. I see you standing in the stifling room, speaking, separation from the British crown, in words that rang the revolution of humanity. We struck the bell, sir.

It was we, laboring through the summer for a common ground, capable of our a public who first struck it. Started the metal singing, fell the kings, like crows across the continent of Europe. Adams. And filled their thrones with what? Gray, faceless, despots worse than any king. Jefferson. Because we had abandoned our great bell, left it to other minded men to ring for other purposes, their own... You and I first quarreled on that question. Adams. First and last. Jefferson. No. At the last I wrote a letter not to you, but to the citizens of Washington. Telling them what our declaration was, what I believed it was. You never read it. You and I were gone when it saw a print. Shall I tell them what that letter said? You and your midnight marchers?

If they'll listen. Adams. We have no choice, but listen. Any of us, letters or violins that Thomas Jefferson starts the music. All men listen. And then it goes on with the letter that he wrote to the citizens of Washington. If you could look those men in the eye, how do you think they might respond if you ask them how fairs this experiment? I think John Adams, or the sense of... is down to earth's sense of reality, power, or think we were a pretty shoddy lot. And that some of our recent behavior had been pretty contemptible, but I think he would be very much impressed by the fact that the United States is an extremely powerful country in a very rich country. He'd be troubled

by what troubles you and me. Jefferson, I wonder. Jefferson was so fundamentally wise about human nature that he might see the tragic events of the last ten years or more as incidents on the way he might take great satisfaction in the increasing civilization of our public life, our concern for the civil rights of others, our attempt to help the civil rights of others. But I'm afraid he'd be pretty sad at heart when he thought about the words of the preamble to his Constitution. But who am I to speak

for Thomas Jefferson? From his home in Conway Massachusetts, this has been a conversation with Archibald McLeish. I'm Bill Moyers. For a transcript, please send one dollar to Bill Moyers' journal, box 345- New York, New York, or 1-9. I'm Bill Moyers.

I'm Bill Moyers.

- Series

- Bill Moyers Journal

- Episode Number

- 308

- Contributing Organization

- Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group (New York, New York)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip-b19fe6db752

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip-b19fe6db752).

- Description

- Episode Description

- Bill Moyers interviews 83-year-old poet and public servant Archibald MacLeish. The poet speaks of his love for his rural home, the value of manual labor, and the joys of old age. MacLeish recalls his career as a law student, poet, librarian of Congress, his six-year stay in Paris, and the fall of France in 1940. The three-time Pulitzer prize-winner reads from his work and discusses his search for an understanding of God and for a solution to the feeling of powerlessness in the modern world.

- Series Description

- BILL MOYERS JOURNAL, a weekly current affairs program that covers a diverse range of topic including economics, history, literature, religion, philosophy, science, and politics.

- Broadcast Date

- 1976-03-07

- Asset type

- Episode

- Genres

- Talk Show

- Rights

- Copyright Holder: WNET

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 01:00:25;01

- Credits

-

-

Editor: Moyers, Bill

Executive Producer: Rose, Charles

Producer: McCarthy, Betsy

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

Public Affairs Television

Identifier: cpb-aacip-60bb118c19b (Filename)

Format: U-matic

-

Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group

Identifier: cpb-aacip-02e803dca30 (Filename)

Format: LTO-5

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “Bill Moyers Journal; 308; A Conversation with Archibald MacLeish,” 1976-03-07, Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed August 12, 2025, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-b19fe6db752.

- MLA: “Bill Moyers Journal; 308; A Conversation with Archibald MacLeish.” 1976-03-07. Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. August 12, 2025. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-b19fe6db752>.

- APA: Bill Moyers Journal; 308; A Conversation with Archibald MacLeish. Boston, MA: Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-b19fe6db752

- Supplemental Materials