Report from Santa Fe; Helmuth Naumer

- Transcript

... ... ... ... ... ... ... ...

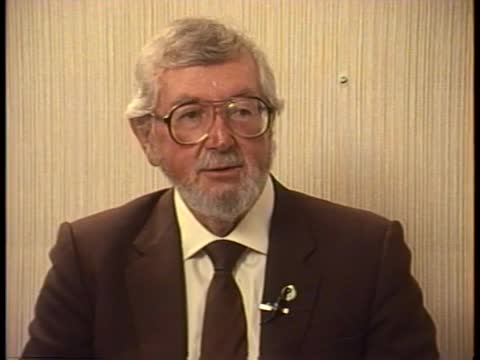

... ... This interview was originally broadcast on the weekend of November 20, 1993. Yesterday, from his office in Santa Fe, Ernie Mills issued the following statement. Helmuth Nomer, a native New Mexican, died Monday, July 25, 1994, at the age of 60, after a long and courageous battle against cancer. He was fluent in the Spanish language and a well spring of information about his beloved New Mexico's culture and arts. His hallmark was his integrity, credibility, and ability to bring forth the best of others.

This program is dedicated to his memory and his legacy. I'm Ernie Mills. This is report from Santa Fe. Our guest today is Helmuth Nomer, who is the officer, the cultural affairs officer for the Office of Cultural Affairs. That's a nice title. I like it. A lot of people always wonder why they didn't call it a secretary or something like that, and actually I prefer it not to be a secretaryal position, because actually you get a lot more done. You raised the question now and raised the point. Give us a little breakdown on how the Office of Cultural Affairs fits into state government today, Helmuth. We are administratively attached to the Department of Finance and Administration, which really doesn't mean too much when the 78 reorganization and what have you. They attach various agencies, but we communicate with them obviously all the time with DFA. But the Office of Cultural Affairs was set up in 78 to bring together all of the museums, the arts organizations, the state library, historic preservation, and that kind of thing.

Right now we have an organization of about 500 employees and spend about $21 million a year. Now everybody out there who's a taxpayer goes, whoa, $21 million, but we make 40 to 50% of that money ourselves. So the state is really only half funding as such, and I'm not going to get off on the funding problems that you have in any state agency. It is a very, very active organization. Everybody in New Mexico who goes around to the museums, those are all part of the Office of Cultural Affairs. If they're dealing with historic properties and renovating them and what have you, then they need to deal with historic preservation. If they're out there looking for arts money, then they come to the arts division. And then we've added two new divisions to the Office of Cultural Affairs in the last two legislative sessions, which was frankly a little bit of a surprise, we're delighted. We have the Farm Ranch Heritage Museum, which will be built down in Las Cruces. And then the big news project of all will be the Hispanic Cultural Center, which will be built in Albuquerque.

Now you already have a director for that. I've talked to him. Now, Ron Behil is the interim director. Ron's really my deputy, if you want to call him, but I don't like deputies. He really is assigned to special projects. And Ron's doing an unbelievable job in putting this thing together. And it is going so fast. It's very difficult for anybody in the bureaucracy, and I'm not a terribly good bureaucrat, as you'll find out very quickly. But in the bureaucracy, they can't believe we're moving this thing as quickly as we are. It went through the legislature, honestly, like a dose of salts. From that point forward, we've been able to go ahead and just move on it. We already know what site we want. We've selected architects. We've got money. And we're moving. I mean, we're going to have that thing up. We hope by the fall or winner of 95. You said you're not a very good bureaucrat, as I will soon find out. I find out a long time ago that you were not a very good bureaucrat in traditional terms, but an uncanny bureaucrat, getting things done. You're very kind, aren't you?

Back during the days when David Cargo was governor, we had an interesting thing happen one time. I had worked with a woman when I was in New York, with the Harold Tribune. And she had been on a waterfront beat, which is the beat I was on, but she was with the Baltimore Sun. And David brought in, Lonson Dave brought in this man to head up our state tourism department, and is extremely knowledgeable. But one of the things he was not that familiar with in the Mexico, and what he really had in the back of his mind was to take about a one or two year period, and almost like a sabbatical and travel this day, get a lot of writing done. And then leave. I found that out along with one of my colleagues when we visited his wife, and I said, you're giving up that job on the sun, come out here and say, heck no, she says, we're going to come out here and say, what are we going to do? We're going to spend a little time here, like a vacation, and then leave. But now, when you talk about uncanny things, when you came back and moved into the office of cultural affairs, for example, I had critics say to me, he's not one of us. And he's sort of like an outlander, and I said, well, I don't think so, because I've known the number family. And I said, he speaks Spanish fluently.

And fluently, your father was a remarkable artist in his own world. But I said, what do you, but I guess he said, well, he doesn't look like. He looks a little like an outsider. I looked like a wasp sometimes. But I think that may come from my German background. My father was from Germany, came to New Mexico to live with a son of the Mingo Indians for about four years, because of the call, my stories, and everything. He didn't really run away from home, although he told us he ran away from home. And I live with a son of the Mingo's. They taught him to ride. He was a perp horseman. And the Santa Fe art colony was really starting to gin a little bit, and he always wanted to be an artist. And so he moved to Santa Fe, and got involved with Carlos Vieira's group of Santa Fe artists. He was a little, let's just get comfort. Tell us about your dad and the family, because he was a remarkable person. Very remarkable. He wasn't a terribly social animal, which bothered a lot of people. He didn't have great success in galleries, because he always felt they took advantage of him.

And he didn't have great success with the museum in New Mexico, one of my responsibilities at the present time, because he felt they took advantage of him. And all the artists at that time used to come out to the house. I used to think that everybody was coming just to talk and baloney and what have you. But it was my mother's great cooking that they were all coming for. And this is depression times. And my father at that time, prior to World War II, was receiving a fair amount of money from Germany, because his family was rather wealthy over there. And at the end of World War II, they lost all of that. And my father, I remember, as I mentioned Carlos Vieira, we always hear about the syncoping thotus in Santa Fe. And the syncoping thotus in Santa Fe were a group of individuals who weren't European trained. Carlos Vieira had a whole group of artists that were all European trained, and they were from Hungary, they were from Russia, they were from everywhere. And it was a huge gathering that they'd have of artists to sit around and complain as many artists do often about not being appreciated and what have you.

So there were really kind of two contingencies, and Will Schuster's group, the syncoping thotus, which was a coin phrase that B. Chauvinay put together, was a group that were not really included. And so as a result, they'd said that the coffee house and complain themselves. Now they were all fine gentlemen, and they all knew one another, and they all worked closely another. My father, as a young man, was very disappointed, he said, in his arrogant way, that there were just no educated women in New Mexico. And a great muralist here in Santa Fe, who died, unfortunately, from a cat scratch. And then Coluzzi said, well, I can introduce you to a young lady that can quote anything the brownings they wrote or anything Shakespeare ever wrote. My father said impossible. Well, she lives in Pecos. So my father went over with his accordion, which he had learned to play many, many years ago, board ship, and went to Pecos, played for the little Saturday night dance and what have you met my mother. I, as a child, always thought they had a very long courtship. It was six weeks. He had a big black packer, and he went down to where my mother was working with the Occamal Indians, which was my grandfather's great thing that he's done for himself and certainly for the Occamas. And we can talk about that a little bit if you want.

But, and so he asked my mother if they she wanted to get married, and she said, yes, so they went to Yuma, Arizona, got married, spent three months in San Diego, and then came back to the wrath of my grandfather. And he was a good German as well. Now my grandmother was the first on my mother's side, was the first Latin and Greek scholar female at Baylor University. And when she got pregnant with my aunt Ruth, they fired her. Well, the only place grandpa could find decent work was at the school of mines in Sicoro. So they had relatives here in New Mexico, so they moved to Sicoro. And my aunt Ruth was born there, and then my mother was born in Sicoro. And then my grandfather had a, a man who owed him a little bit of money, and he couldn't pay him off. So he gave him this wonderful strip of property, which is at the bottom of Pecos, little village of Pecos, all the way down to what is now forklightening, and then it wasn't forklightening. But he had 300 acres of just strip down the river, which is absolutely fabulous, which was later inherited by my cousins, who were very young and sold it instantly, which they cry every time they come back.

That's the long moan. Oh, the big moan, yes. But, and then my father had a little cabin, as such, out on the sand Sebastian ranch, and that's where we all grew up, and eventually became a 16 room house that was built with slave labor, my brothers and myself. And so we had a, you know, and we had a very joyous life growing up, actually. We had great horses, he raised Arab horses, and was a fine horseman, member of the sheriff's posse for many years. And when I was a kid, one of my little claims to fame was I could track anything being in the woods. And so when I was about 13 and 14, I started tracking prisoners that was escaped from downtown here in Santa Fe. They were all pen road, right, right, right down here. Until I think 61 or 62, it was down there. And we would go ahead and I'd have to track them. I had a couple of scary, I find a quit because a prisoner grabbed me from behind the bush and said, gotcha kid. And scared me to death. And of course they captured him and I wasn't injured, but nevertheless it was scary. So I said, I don't want to do that anymore.

And yet there's hostage stories, you know, you and not situation, you know, hostage in a bath, you know, absolutely. And Ernestine Evans once was a hostage in the same, the old pen. Have you found that when you took over this road, and again, we're one of the major concerns, I think we have in the state now, is with cultural sensitivity, the cultural pluralism, and breaking down these barriers we have. Any experience that you've had, for example, with your grandmother having been fired, it was your grandmother, am I correct? It was fired from Baylor because she was pregnant, you know, in those days. Or when you look at the situation in your role working with the museums and recognizing that sometime, and I had heard these complaints going back 35 years ago, the artists saying, I don't, they put my stuff in the basement at the museum and the complaints. Has that affected you and your perspective toward your job and culture of affairs? Absolutely. I think one of the, one of the most wonderful things about Santa Fe in growing up here was that we were really not taught a prejudice. I think if we had any prejudice against other people, it might have been at that time when I was growing up against Texans, although I worked in Texas for 21 years, and I love them. They're wonderful people.

There's very outspoken a little, you know, they have a great deal of pride, which New Mexicans sometimes don't have, which is one of the things I would like to see us build up much more, teach more history in the schools, let people know the cultural differences that exist, so that we can, we can celebrate those differences rather than putting them down. You hear someone with an accent and you think, oh, well, they're less than I am because they have an accent, whether it be Hispanic, Chinese, or what have you, which is really a shame because what you need to do is learn from the accent or from the language, the difference that that culture has that you can learn from, and that's the number one thing that can happen. In my career, when I started in Charlotte, North Carolina, after I left New Mexico from Towsky Valley, I went to Charlotte to run a small museum, and of course the South at that time, this is 1959, 5859, was totally integrated, and everything was building up in what have you, and it really bothered me to see all the little children who were so segregated, and the black children couldn't come to this wonderful children's museum, which I was building. So I integrated it, what I went through, and bodily threats, and people screaming, and yelling, and what have you, but we were the first public institution in Charlotte to go ahead and integrate.

When I went to Fort Worth in 62, it was the same thing, except we had three cultures there, we didn't just have the Afro-American and the White, and for Earth, we had the Hispanic, the Afro-American and the White, and none of them were using this wonderful, huge, huge children's museum. It was the largest one in the world at that time, and it really bothered me, so I just went ahead and integrated that, very subtly. You know, if you're going to wave the flag at the news media and what have you, and say, I'm integrating, then you really got trouble. We just did it subtly, we just did it, and I had my life threatened many times, and I had lots of little preschool children pulled out of preschool, and that kind of thing, out of people's ignorance. And then I tell every one of them, you will be begging me to put that child back in in school, but I've got 400 on a waiting list, and you won't be able to make it. And every single one of them, who jerked a child out of school, called back and said, I want them back in, that was wonderful, it was one of the great things.

I go through the period, and we sometimes think these things happened by magic, but I remember when, back during Governor Burrow's administration, and at that time, when we used to look around for some of the artifacts and state government, you know, the records. And we said, well, that might be over in Ernie's basement, or, you know, we had no idea, there was no collection. So at that time, the first record system, the first archives, was put into being a Harry Casey, believe it or not, who worked for me, was the first temporary archivist at that time. Later, we had Joe Halpin come in, and it became a very formalized institution. This is part of your agency, and as I believe. Records and archives are not a part of our agency. They don't come under... State Library does. And there's a new task force that was just put together that Laura III, the Secretary of GSD, General Services Administration, and they've visited 17 different sites across the country, where they have combined. Since I took office, I've always been an advocate of combining state library, and the records and archives center, because they have so much in common,

and what I'm after, from my perspective, is an information center, a statewide information center. Well, every community's got a little library. They're all tied in by computers. And I would like it if a person in Hatch, for instance, wanted to know their driving record. They could go to their state library, the librarian or person there, the information specialist. But go ahead and punch up their name, their serial number, and what have you. It'd go via the state library, tied in to the motor vehicle department. And five minutes later, they got it back, a printout, they paid their five bucks, and they got it, rather than waiting six weeks, which is what you've got to wait for, a birth certificate or anything, if you're out in the hinterlands, and you need it, you've got to ride up here, and then it takes so much time. You've got to try to find a building. That's right. We're beyond that with all our communications and everything we have now. And the state of the art is to be able to give people historical information when they need it.

I mean, the main job of the state library is to store governmental information. I mean, that's really their main job. When I came in and Karen Watkins came in, who, by the way, is superb a state librarian. She and I agreed that we need to get rid of the cookbooks, and we need to get rid of the novels, and we need to get rid of those things that the Santa Fe library ordinarily would have. So we transferred that to various state libraries throughout the state, and focused much more on what the mission of the state library is, which is to be a legislative resource, to be a public resource, so that if you need information, you should be able to get it. And now we do a couple of specialized things there, like books for the blind, which comes centrally out of the place, and a variety of other... Playboys for the blind, too. Playboys. Yeah, they got those. Oh, yeah. Well, they got everything. My father went blind at the end of his last four years, which was really tough for an artist, and he used the book for the blind constantly. He loved them, and it was great. It's a great program.

Knowing the non-conforming bureaucrat that I do, Helmet Namar, what has happened with cultural affairs in recent years is part of a plan you have in your mind. It's somewhat purposeful. It's not a catch-ass-catch-can situation. The way in which you get along today with the legislature is remarkable compared. You had pretty tough times starting off. Well, I replaced a very popular person who's marvelous, Clara Apadaca, who is Governor Apadaca's former wife, and the legislators loved her. And she's worth loving. She's a superhuman being. And so it was very difficult coming in, because, as we mentioned earlier in the program, I look a little bit like a wasp, and so they didn't realize my true heartfelt and soul kind of feeling for New Mexico, and the importance of New Mexico. I see New Mexico as the most unique state, and I've lived in a lot of them during the 30-year period I left this community. And I see a lot of them that don't have any uniqueness, or they all want to homogenize everything so everything's the same.

In this state, we're fighting that. And I don't want to see the homogenization of this culture. I really want, as I mentioned earlier, to celebrate our differences, to be able to, well, let me use an example, a little anecdote, in the Hispanic Cultural Center. We see, and across the country, news media and individuals, and want to say, oh, the Hispanics can never get along, which is really silly. But nevertheless, but there's a reason that you see a lot of change, or clashes between Hispanic groups of people. And the reason for it is that we don't realize that each one has a different culture. We have a common thread, which is a language, but we don't have that common culture among all of them. A Cuban is totally different than a Venezuelan. Northern New Mexico, Hispanic is completely different than Southern New Mexico, Hispanic, and their cultural approach. They have a common language, but when you get these different groups together, you're not mixing cultures.

And when everybody recognizes that we have a cultural difference, which is wonderful, and we need to celebrate it, and we need to maintain it. I mean, one of the things that we did in the arts division, when I first came in, and I've been sorely criticized for too, we quit giving to the big major organizations as much money. We took that money, and we focused it into rural arts and culturally diverse arts, because that's the specialized thing we have in New Mexico. That's what makes this unique, is the San Teto, for instance. That's what we need to celebrate, and continue, otherwise, we'll homogenize, thanks to television and materialism in this country. We are homogenizing the whole country. We want everybody to sound alike. Somebody with a Southern accent from Houston, for instance, or even Eastern New Mexico, we kind of say, oh, well, they're uneducated. Has nothing to do with their being uneducated. It's part of their cultural difference. And we need to accept that cultural difference, and say, I'm going to learn from that cultural difference. I guess it would be extending the cultures we think about as being brown and Anglo.

Oh, absolutely. And extending that into economic cultures, the culture of sexual preference and such, all of these things. I'm my home station, for example, and my radio broadcast that covered the state, is a bilingual station. And I've always amazed, because up here, when we look at some, it's only recently, like the Reptory Theatre here, which we say, believe it or not, we are interested on this bilingual station and what's happening in the theater. And especially when you stop and look at the marvelous artists we have who aren't Hispanic. But this is something that we're only touch upon. I would rather, we are going to be looking at the going into the spring, at one show dedicated only to the arts, as it affects, and not bilingual in the sense, or bilingual. Indian artists? No. Hispanic artists, the Anglo artists. But again, art forms that, as you say, are different. Why not homogenized? One of the problems that we face is that some people will take their cultural difference and try to use it as a stepping stone.

And we face this very often with people who say, well, they won't show Hispanic artists at the art museum. Well, that's not true. The bottom line is better, or a woman's artist, or what have you. The thing that's terribly important is that you are celebrated as an artist, and not because necessarily of your background or your ethnicity, or anything like that. If you really want to be a famous artist, then you have to focus on getting to be a famous artist and not using other things as stepping stones. Now, we have fabulous Hispanic artists. We have fabulous Native American artists. Now, of course, we have fantastic Anglo artists. They all come from different cultures, approach things from different perspectives. And what we need to do is show those perspectives so that other people can learn from that, because you know, as well as I do, that you only learn what you discover yourself. You do not learn what other people are telling you. You have to get in there, and you have to ask the questioner, you have to get involved in it so that you know, and you learn it yourself.

It's that self-discovery, which teaches people to teach themselves, which is what, you know, our education system and everything needs to someday realize that the whole format and how we're presenting things and everything is absolutely backwards. And it really is backwards, because I created, in Fort Worth, a little school called a preschool. And from that preschool, I developed a curriculum and a philosophy and everything about teaching three, four, and five-year-old children. During the days of Roger Stevens at H.E.W. back in the 60s. I happened to know one of his right-hand people, Katherine Bloom, and they said, you know, we were sitting there having a conversation, and she said, we've got this big, huge problem. We have to come up with a national model for this new preschool program we're going to do. And I said, come study my preschool. Parents stand 18 hours in line in order to get into that preschool. It's first come, first serve, very unique philosophy, et cetera, et cetera. So they came down with a crew of people, spent three months with us, and out of that game had started. And the thing is that because of the philosophy of having not expecting children, you see that, one of our big problems, we expect them to, on a grading system to have learned so much.

Well, there's no way to know how much they've learned, what they've memorized, yes. But what you really learn is a whole different thing. It may be subconscious. It may be totally conscious. But it's how you have learned it, and how you take it in as a human being. The biggest and most difficult thing to do, again, to the cultural side, is to have people accept that and learn, and to self-discovery is what they're after. They need to discover the difference between the Hispanic cultures, even though they have a common language, or the difference between Occamand, Santa Domingo, even though they, in essence, have a similar language. But they're two different cultures of people. You know, I want to go back for a moment to your grandmother. About what was the year that she was asked to leave Baylor because of being pregnant? She was 19, I think it's about 1903. She was called the Poetists of Baylor. She had a very good history there, and she loved Browning and Shakespeare.

She memorized all that, and she passed that on to my mother and her two sisters, because that was their education. There wasn't a lot of education in New Mexico. My mother was born in 1912 when New Mexico became a state. New Mexico, I remember even as a kid, having to drive to Pecos, going out, what was 285 now? I was a dirt road. It's almost symbolic. You take a woman who had been married to a professional, a person in a medical profession, and in a sense, you become the housewife of a professional. I did a show before we met today to take this show with Dr. George Goldstein. Here's the good right hand of George Goldstein. Suddenly moved into this field. A lot of work on a volunteer basis, then moved into the hotel, motel industry, and now is working for your agency. The kind of person who can call people like me and have markers as long as you're armed, but almost indicative of what we look for and say, let's open the door to people. There's a marvelous change. I don't know how you came up with her. Sometimes I don't know how you live with her. There's a really cute joke that Mickey and I laugh about because she came in to see me. Someone suggested that I was looking for a legislative liaison.

She came in to see me, and the minute I'd known Mickey off and on from time to time, and I decided I would hire her and we agreed on while little money we had to do it, and everything like that. Of course, the first thing I have to do is go and introduce you to Governor and Mrs. King. She started laughing. Of course, she'd known them for years and years, and very close to them, but I didn't realize that. I had no idea. I hired her on her ability to do the job that we need to have done, and she had done a marvelous job. How much I want to thank you for. You believe that half-hour is gone by. It's too fast, and we'll be doing other shows coming up, because I also want to look at you. I know in the back of that non-professional bureaucratic mind you have, you have plans laid out for the next 18 years, and we'll talk about them before this next session. Our guest today is Helmeth Nomer, who is the Cultural Affairs Officer for the Office of Cultural Affairs in the state of New Mexico.

I'm Ernie Mills, and thank you for being with us on report from Santa Fe. This interview was originally broadcast on the weekend of November 20, 1993. Yesterday, from his office in Santa Fe, Ernie Mills issued the following statement. Helmeth Nomer, an eight of New Mexican died Monday, July 25, 1994, at the age of 60, after a long and courageous battle against cancer. He was fluent in the Spanish language, and a wellspring of information about his beloved New Mexico's culture and arts. His hallmark was his integrity, credibility, and ability to bring forth the best of others. This program is dedicated to his memory and his legacy. Thank you very much, thank you. ...

... ... ... ...

- Series

- Report from Santa Fe

- Episode

- Helmuth Naumer

- Producing Organization

- KENW-TV, Eastern New Mexico University, Portales, New Mexico

- Contributing Organization

- KENW-TV (Portales, New Mexico)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip-ab0eb36975e

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip-ab0eb36975e).

- Description

- Episode Description

- This episode is dedicated in memoriam to Helmuth Naumer (1934-1994) and is a rebroadcast of a previously recorded interview with him from November 1993. Helmuth Naumer, cultural affairs officer for the Office of Cultural Affairs, joins Ernie Mills to discuss the office and their role in state government, his background, and how that impacts his work.

- Series Description

- Hosted by veteran journalist and interviewer, Ernie Mills, Report from Santa Fe brings the very best of the esteemed, beloved, controversial, famous, and emergent minds and voices of the day to a weekly audience that spans the state of New Mexico.

- Broadcast Date

- 1994-07-30

- Created Date

- 1993-11-20

- Asset type

- Episode

- Genres

- Interview

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:30:35.834

- Credits

-

-

Guest: Naumer, Helmuth

Host: Mills, Ernie

Producer: Ryan, Duane W.

Producing Organization: KENW-TV, Eastern New Mexico University, Portales, New Mexico

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

KENW-TV

Identifier: cpb-aacip-62b5895c36d (Filename)

Format: 1 inch videotape

Generation: Master

Duration: 00:28:55

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “Report from Santa Fe; Helmuth Naumer,” 1994-07-30, KENW-TV, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed June 24, 2025, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-ab0eb36975e.

- MLA: “Report from Santa Fe; Helmuth Naumer.” 1994-07-30. KENW-TV, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. June 24, 2025. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-ab0eb36975e>.

- APA: Report from Santa Fe; Helmuth Naumer. Boston, MA: KENW-TV, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-ab0eb36975e