¡Colores!; 1503; Albuquerque's Historic Railroad Shops; Interview with Leo Hernandez; Part 1

- Transcript

When I first came into Machine Shop 5, we were naturally awed by the size of the building, and at the very first day that I walked into this building, why the big crane on the other end of this building right behind me had a locomotive in the air and was going sideways with it to the other end of the building. And I noticed guys underneath working like as if nothing was happening, I thought to myself, I don't think I'd do that. But yeah, when I'd crane picked up something that heavy and you would think the building would react as far as, no, the building was so sturdy that picking up a locomotive like

that and taking it across because everything is supported by these huge beams. And it didn't hardly make that much noise, it was very quiet. Of course, everybody else was busy making their noise, you know, riveting, welding, and all kinds of lathes and stuff all doing their job, everybody making parts. So it was very interesting when I first came in to the building. And of course, you had almost 250, 300 employees working on this floor at any one time. And so it was very interesting to find out how you were going to fit in to this huge apparatus, I would say, huge building, I mean, everybody doing their thing.

Let's do that again and I'll change the perspective of size. And are we getting any of this little animals sound? Okay, great. Yeah, it's good. Yeah, so if you can just give that to us again, we're going to get it a little different. Okay. That'd be wonderful, thank you. So just, yeah, so just what did you feel, what did you think when you first came into this building again? What I felt and what I thought when I first came into this building was the fact that it was so enormous. And you walked in here on the first day and you see the huge locomotive crane that sets over behind me up on the top end at a locomotive in the air. And of course, back then, you looked at something that big, that huge, and you think that the building might creak or shake or something, but no way.

I mean, it was the building is so sturdy that a movement like that was very skillfully handled by the crane operator, as well as a foreman who was judging how to stop when to stop so that the locomotive crane doesn't swing the locomotive before it stops and sits at downward where he wants it. And the amount of people working on this floor, something like 200, 250 people all doing their thing, and like as if a locomotive wasn't even in the air, they're so used to it. And that was my first feeling, and the second feeling was the fact that everybody had a job to do.

And not everybody was sitting there watching the locomotive like I was, and so I'll never forget that feeling of being able to come in and see something that's spectacular. Something you don't forget. The sounds that were in this building were coming from sounds like people across this back wall here doing their grinding, welding, and tightening bolts with huge, we had no electrical tools, there were all air operated tools that, of course, air when it's operating something, it makes a lot of noise.

And then of course you also have a lot of hammers that are working. You have people that have got their lathe operating at full speed, and this area right here was full of lathes back then, and you had the constant noise of motors turning these lathes and people making different parts. The parts that they made were things that they couldn't go down to Napa to pick up because locomotive parts are not standard. Something is made with a purpose of making a pattern, and then that same man makes a half a dozen of what he really needs as spare parts for down the road on locomotives, especially the repair of the steam locomotives here.

They were completely void of any parts that you could buy on the outside, and of course when you had people making your own parts, why that was a beauty out, you'd make the part the way you wanted it made, not according to some engineer who never rides a locomotive. So those are the things that the noise came out of air, welding, the lathes doing a lot of, making a lot of noise, and right behind me over to my right at about the center of the building there was this machine that pressed the wheels off and on the axles for the locomotives, and the pressure that that machine had to bring up to pop the wheels off and put them back on was in the 150 and 200 ton rating, and when a wheel was popped off you heard

it all over the shop, just like a big bang, like a cannon going off, and of course putting them back on was quiet. You could mention that when you first walked in here you were wondering how everybody had their place and did something to get the trains, where was your place? When I first went to work in here, my place that I was working at was, and of course they started all apprentices with, and they still do probably, they started him with a mechanic a machinist who was already a machinist, and my first job was trimming and making brake appliances for the brake hangers to work on, and it was a combination of a small lathe as well as a unit that done a lot of cutting and aligning for different brake rigging.

Large locomotives, small locomotives, passenger locomotives, and the sizes were all different when they gave you a number, why you traced it to the proper size of shim that that locomotive used, and so you made a pile of those probably, one day and next day you'd be working a different locomotive, and so on and so forth. Okay, the sounds that you might hear on the outside that sounds like the type of sounds that came from inside the shop, where sounds like, for instance, if you go by a shop that

is building trailers for your 18 wheelers, and they're doing a lot of hammering, and then of course with railroading, at that time they used a lot of red hot rivets, and they pounded them in place with their hammers to make a button on the opposite end of a rivet head, kind of like the rivets that you see on these pedestals here. That sound is always familiar with what you could hear here in the shop, and but the lot of sounds that you heard in the shop like this was air escaping, because people using power tools that are powered by air, while you'll always hear that air exhaust like in

a paint shop or something like that, but then you multiply that by about 200. And you get that sound that you would hear in here, as well as when they fired up the locomotives, why the locomotives would have all kinds of air pumps working, and pump in water through the system to superheat it and give you power for steam. All that is sounds that you would hear, such as when I was a jet aircraft mechanic on the flight line, and you hear the exhaust of these jet engines, why that would be comparable to what these locomotives noises that they were making, pump in air, water, fuel, coal, and then of course the huge exhaust that you'd get through the chimney on a locomotive,

why it would give you a sound of maybe a small jet aircraft operating on a flight line. You might say people who are learning the craft, they doubled them after the steam locomotives went out, which is odd, because you would figure that they needed more people while they were building locomotive parts, but with steam locomotives, they were more special parts that railroads made to make their diesel engines better, and that was all basic really if you look at it the right way, because you always had more diesel locomotives because of the increase in traffic that you would get at a later date.

Crow was really loud, didn't he? I was going to ask you, what kind of people did you work with, when you came out of your apprenticeship and you looked into the shops, did you have a lot of commotory with the other workers, could you hear the sound of the machinery, what was it? Well when you finished your apprenticeship and became a full-fledged machinist, why the jobs that you bid were usually the jobs that nobody else wanted, so your newest mechanic or newest machinist, why I fell into those jobs, and I say this because it was a fact that your older machinists were not that comparable or comfortable with working on diesel, because they were old steam locomotive machinists, and they left the diesel to us younger guys,

and so when we went to work with an older machinist working on a diesel, he usually left a lot of parts ordering, he left a lot of the, what you might say, measurements that were used in thousands of minutes, to where your older machinists, they worked with 30 seconds and 64th of an inch, and so the latter steam locomotives used that type of a measurement to where steam locomotives, I mean bigger part, your diesel locomotives were in the thousands of an inch, bearings, races, components that worked at high speed, all of that was closer

tolerance, and so you had to get along with the older machinists, and you had to work as a team rather than criticizing each other, that got you nowhere. It's going to be inches, what is that in reference to, what does that mean? The reference of inches as maybe you want to compare them to thousands of an inch, you had bearing races that worked in closer tolerances, and so you used thousands of an inch to get your right bearing clearance, and roller bearing clearance, as well as ball bearing clearances, and so when you used that reference, it was closer than the old measurements of 30 seconds and 64th of an inch, and the reason for using higher clearances with

diesel locomotives was that you had that particular part, either carrying an excess amount of weight as far as roller bearings goes as compared to ball bearings, and the performance of a certain piece of equipment lasted longer with closer tolerance, and so you wanted to achieve that increased amount of tolerance, and using the comparison saved the railroads a lot of money if you built something that held up, rather than something that would run sloppy and break down before each time, causing us an accident out on the railroads. The jobs that you bid on, as being a new machine that nobody else wanted, were jobs that were

in closer reference to high speed, higher heat, and more of a reference to things that a locomotive had to use to achieve their high speed track movement, and one of those jobs the main job on some of that stuff was the governor that the locomotives used to control the speed that maybe four locomotives would be pulling a large amount of cars, and all these four locomotives running up front, they had to work in unison with each other, and so these governors had to be set precisely where four locomotives could work with each other

without jerking things around, and if you didn't adjust a governor on one particular locomotive to work in unison with maybe three others, you had a problem. One generators had a lot of fiddling to do with that, like the people who called fiddle with this or fiddle with that and make it work right, so when I went into my first job, it was with steam generators, and steam generators do nothing on the railroad, on the tracks, on locomotives, but for any steam back in the old days for both heating and air-condisting, and so steam generators used an automatic system in them that would turn on and off automatically.

If you didn't know how to set one like you're supposed to, why they broke down between stations and people who would either get to sweat in too much because of no air-condisting or in the winter time, it gets so dog on cold in those cars if you didn't have steam to keep the old-time cars warm, and I don't know whether you want to hear how they work now without steam generators. He was as colorful as he was smart. He had a photogenic mind, and he never forgot anything, I'm just trying to think of the gentleman's name. He lived right out here, two blocks away, and his son, his son, come in here and work

on a apprentice job, and he's too boring for him, so he quit, and him and I were going to school at the university together at night, and he is working out at Los Alamos now in conjunction with Sandia, and his job was making and building motherboards and stuff for all of your interceptor rockets that would bring down an airplane, and I cannot think of, I'll think of it later on, probably, you ready to start? Your question was the worst jobs in here when you were a new machinist, and you were one of the worst jobs that came up was working in the pits, and working on the locomotive

wheels and brake rigging, because the pits were not high enough, and you had to stoop all day to work underneath a set of wheels and stuff, and that was when they were still mounted on the locomotive, and it was for some reason another, they had to have the locomotive back in a couple of weeks so they'd bring it in for a little while, and you do the modifications to the brake rigging, and everything is just heavy and hard to lift, and you just have to use two or three people to help you lift heavier brake rigging than you would otherwise. Later on they started taking all that heavy brake rigging and stuff, and running them up on stalls on this other end of the shop that this end here, and made it a lot easier

for a lot of the guys to do that. Now the job just above that that was kind of a nuisance, really, more than anything else, was taking automatic steam generators, and your automatic water pumps that kept the locomotive warm when it was out on the road, so it wouldn't freeze, when the locomotive wasn't working up to full speed, say you're parked and you're waiting for something to happen, a derailment or something that you can't get around, and it's snowing, you gotta keep your water pumps running, and your steam generator running, and you have to bring those when they come in here, and the pipe fitters and yourself work together to tear them down, and everything is just full of sutt, and a lot of fiber, not fiberglass, but that insulation, and the

insulation is so thick in the air because you're using air tools to take stuff apart, it just takes this insulation, just blows it up like a little cloud in the shop, and that's another thing, you could stand on this end of the shop and look across, and you could just see this cloud of that insulation floating in the air all the time, and we're breathing all that, and I'm lucky I haven't been tested for as far as my lungs and stuff being full of it, and I've been lucky I don't have any problem at all, like other guys do, I don't know, maybe I didn't breathe deep enough, but those jobs were some of the dirtiest and hardest jobs that all of your people with less seniority had to put up with, and the air,

the air was always, if you had somebody next to you who used to like to take and spray the floor to keep his area clean while he just got everybody else's area dirty, so that was one of the worst jobs that you could have, and some of the guys started putting up their own exhaust fans in this area here, especially, there's one right there that the exhaust fan was put in there because his gentlemen could not actually see his work because of the dust and stuff, and when you were under a hood doing all your welding, where then all of that smoke from the welding and stuff come right up into your helmet, and an exhaust fan helped pull all that out, which was later, a lot of these windows here were equipped

with exhaust fans at that time. What was dirty about working in the pit? The pits always had oil and the grease, that grease compound that they used in the old days, it was like a thick black grease, and when you got it on your foot, it's like taking some mud that is so thick, you try to take it off, and it just won't come off because it's so sticky, and that lubricant was used on what they call packing the cellars in your boxes, that the wheel axle turned in, they packed the bottom in with grease, and then when the axle was turning, you had a type of compound in there that clung to these

axles to keep the axles cool, keep grease on them instead of having the, because oil would just drop down and it just wouldn't stay with your friction. The grease would keep your locomotives from, locomotive axles from burning up, and they, I would say it was like threads of rags, just threads themselves, why companies used to make those, and they used to pack the boxes underneath the axle with this, they called it waste, W-A-S-T-E, and waste kept the lubricant up against the bottom of the axle, so when the axle turned, why it would pick up this slippery grease and would carry it up to the

bearings that were on top of the axle, and that was dirty because that stuff got on everything, and they tried to keep the pits as clean as they could, and then they'd spray them with this white dust, they called it, oh, they put it now in soft water to keep water soft, and it's like a lime, and lime would actually take and disperse all this grease, and they take the lime and sweep it and would take the grease out of the pit. It was a no-brainer, you know, you put on a brake shoe, and on top of the ramps, because right in here, on the other end, you had ramps that were up this high, and you would work

the engine on the locomotive off of these ramps, because the engine is up that high, the actual locomotive engine, diesel engine, and so we were always working up there assembling your diesel engines, and they were very intricate, and so you used more than likely you'd find all your young guys up there doing that. The older guys, they'd take, like you say, they would take the jobs that were a no-brainer, because hey, they were just waiting to retire, they're not going to do anything more than just what they wanted to. That's that number for that solenoid, and that 2100 locomotive in the electrical side. He says, what do you mean?

He says, the input or output solenoid. The input is 10.00271, and so on, so on, so on, so you know. And I ask him, Alex, how do you remember those? Oh, it's easy, he says. Well you do, just say it one time, register's up here, and you never lose it. He was good. Okay, Amber, a gentleman that worked in the pits all day long, you know, a standard eight hour shift, and in the old days understood they worked 10 and 12 hours a shift. But a man that would go to work with a clean pair of overalls, at the end of eight hours, you could take a putty knife, and you could take and scrape the grease off of his trousers and his arms, and his chest here would be just, the grease would be there.

I mean, you take it and take off what you could, and then take those home, and they'd have to, they'd have to boil them clean. And in the old days, they used a homemade soap that the women, railroad women had to use, and boil those coveralls clean, and then rinse them out two or three times. My dad's overalls, I remember taking him lunch, and he'd come to pick up his lunch to the door because there was so much noise in the building that it bothered my ears. And so he'd pick up his lunch, and you could see the grease just shining on his leg, pant leg on the top and his chest and stuff, and his hat would be just a bog of grease here

and there, where he had to work in between the, being a machinist while you worked in between underneath on top, on the sides of a locomotive. And it was one reason why I thought I would never learn to like a railroad job. But then when I started, why it wasn't that way, the decals were in, they were cleaner to work on, and I'm going to say that it took a little bit more, I would say, of pronouncing why it would've been.

- Series

- ¡Colores!

- Episode Number

- 1503

- Raw Footage

- Interview with Leo Hernandez

- Segment

- Part 1

- Producing Organization

- KNME-TV (Television station : Albuquerque, N.M.)

- Contributing Organization

- New Mexico PBS (Albuquerque, New Mexico)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip-9c8cae6822a

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip-9c8cae6822a).

- Description

- Episode Description

- Footage shot for the ¡Colores! episode "Albuquerque’s Historic Railroad Shops." Like the bones of some odd prehistoric dinosaur, perhaps no other buildings in the Southwest have such a presence or history. The sprawling buildings sit quietly just outside Albuquerque’s downtown. Walking through the empty interiors is an eerie experience, miles of glass windows, cavernous spaces, the remains of a shop bulletin board and curious remnants. For over 70 years the Santa Fe Railroad operated a huge repair and work shop in Albuquerque. At one time, the shops could rebuild over twenty locomotives in each of the huge five-story, glass story buildings. The impact of the shops was so pervasive, townspeople set their clocks to the shop whistle as it signaled the beginning and end of the workday. The shops were the heartbeat of the city and economic engine that helped power a nation. This documentary takes a fascinating photographic voyage through these tremendous buildings and hears of the remarkable experiences of the people who worked there.

- Raw Footage Description

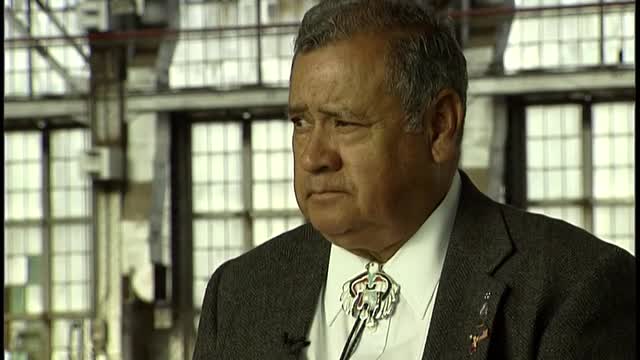

- This file contains raw footage of an interview with Leo Hernandez about his experience first arriving to work at the Santa Fe Railroad Shop in Albuquerque, New Mexico as an apprentice.

- Created Date

- 2004

- Asset type

- Raw Footage

- Genres

- Unedited

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:33:43.389

- Credits

-

-

Director: Kamins, Michael

Interviewee: Hernandez, Leo

Producer: McClarin, Amber

Producing Organization: KNME-TV (Television station : Albuquerque, N.M.)

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

KNME

Identifier: cpb-aacip-9a107edf8eb (Filename)

Format: DVCPRO

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “¡Colores!; 1503; Albuquerque's Historic Railroad Shops; Interview with Leo Hernandez; Part 1,” 2004, New Mexico PBS, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed June 17, 2025, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-9c8cae6822a.

- MLA: “¡Colores!; 1503; Albuquerque's Historic Railroad Shops; Interview with Leo Hernandez; Part 1.” 2004. New Mexico PBS, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. June 17, 2025. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-9c8cae6822a>.

- APA: ¡Colores!; 1503; Albuquerque's Historic Railroad Shops; Interview with Leo Hernandez; Part 1. Boston, MA: New Mexico PBS, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-9c8cae6822a