Bill Moyers Journal: International Report; 104; A Report from Africa and a Conversation with Robert McNamara

- Transcript

BILL MOYERS' JOURNAL: INTERNATIONAL REPORT

"A REPORT FROM AFRICA AND A CONVERSATION WITH ROBERT MCNAMARA"

FEBRUARY 6, 1975

BILL MOYERS: These are rice fields in West Africa. The soil here is fertile. The people can farm the land, grow their crops, tend their herds and raise their children.

But the people are leaving. They are leaving because there is a plague upon the land. And the plague is blindness. The waters that nourish life also breed darkness, depriving people of their sight and livelihood, driving them away from the land that could sustain them.

These are vibrant people. If the blindness is overcome, they can stay on this land. Life can be normal again. And eyes meant to see can see.

I'm Bill Moyers.

There are about one billion people in the world who live on what Robert McNamara calls the margins of life. They live without enough to eat and with very little hope that things will get better. There are many reasons why they're poor and they usually can't control those reasons. Some are the victims of a cruel and capricious climate. Others were born where nature left nothing to grow or well. Still others live where opportunities are frustrated because of overcrowding, disease, corruption, and exploitation.

In this edition of my Journal, we'll meet some people whose lives could be better, were it not for a tiny, winged insect that thrives on the source of life itself. And we'll talk with the President of the World Bank, Robert McNamara who believes that it doesn't have to be that way.

These are the people of the Volta River Basin in West Africa, where river blindness is a plague upon the land. The area covers parts of seven countries, Upper Volta, Ivory Coast, Mali, Niger, Ghana, Togo, and Dahomey.

Thousands of people in villages like this suffer from onchocerciasis, river blindness. The disease impairs vision and can ultimately destroy all sight. River blindness is transmitted by the bite of a female black fly.

Dr. Nemo of the Ministry of Health in Northern Ghana explains.

DR. NEMO: When this fly bites people, it transmits a worm which we call the onchocerca volvulus and this worm is the smaller one. This smaller worm or the microfilaria moves in the subtissues of the human body and it keeps moving, wandering around, until it grows and becomes the adult. And you can get one male, one female always in a nodule, mating together to produce many of the infant worms and it's usually these infant worms which cause the trouble. They wander around the eye, produce certain changes and cause blindness.

MOYERS: To the people of West Africa, the first of gifts is water, their most precious resource. But these fertile river valleys are also the home of the black fly. Entomologist Rene Le Berre of the World Health Organization.

RENE LE BERRE: In places like this, with fast running water, the fly is living. The female lays eggs on the leaves, on the grass, and on the rocks, and the larvae develops on the resting place. They become pupae. And the females and males hatch. After a while, the female is biting man to suck blood. And there is females, for example. Takes about two or five minutes for a fly to suck blood. After this fly is going away, and after three or four days, this fly is laying eggs in these rapids, on the leaves or on the rocks. And a new generation begins.

MOYERS: River blindness affects people in many parts of the world but it's most severe in the seven West African countries. Until recently, anyone who lived near the river almost certainly would have been bitten by the fly, some repeatedly, until the blindness came. The river valleys are oases in a dry, parched land. For people and animals alike, the rivers established the rhythm of existence.

Without water, no life survives. But near it, a person can suffer as many as thirteen thousand fly bites in one day. Thirteen thousand. There is a familiar cycle of life in the villages along the Volta Rivers birth, death, work, and play. But with river blindness, the social pattern abruptly changes. Women do the work of men, boys and girls the work of adults. The blind are always with

them. In some villages, as many as fifteen percent of the people are totally without sight. Many are men in their thirties and forties, men in their prime.

MAN: When you ask, river blindness, yes, a lot of people are blind. But they eat. So safe people has to work very much for them, for children, for old people, for blind people.

MOYERS: The burden on the families is enormous. Here the father, mother, and three children are blind or suffering from other diseases. Only one son, age eleven, is well. On him is the weight of harvesting, planting, and carrying water from the river. But he has the all too familiar nodules; like his father he, too, will one day, be blind. Who will take care of the family then?

Farming here is hard. Usually it's the man's job but it's even harder to sow and harvest when you cannot see. Life in the villages must go on, supported mainly now by women and children. In time, the afflicted village begins to die.

Young people leave as soon as they can, trying to escape the fly. There are fewer marriages and children. And the blind, the blind live on in darkness, isolated, lonely, and dependent. Life at the end of the stick.

Chief Gaubre Saubra rules the village of Foungou on the White Volta. His village is dying. Twenty-seven of the two hundred people who live here are totally blind. Others are beginning to lose their vision too. Chief Saubra cannot quite believe that a small, black fly has been the thief of his sight. But having lived here all his life, he knows well the old village saying, "The River Will Eat The Eye".

To these people blindness is another of life's mysteries, a fate they can neither` understand nor overcome. Its toll is high. Along the White River Volta, almost fifty villages have been abandoned. And more are dying. If the black fly continues to thrive here, this rich delta country of Africa could become a wasteland.

MAN: The population is moving from the river. Because when you stay very close to the river, as the time, the fly will come over and bite them, and when they move away from the river, the unfortunate thing is that they go on to some barren land so that they can't farm or they can't get food produced from their farms.

MOYERS: Ten million people spread over seven countries are potentially the victims of this cycle. They live in a region of great agricultural possibilities. If it is developed, they could feed themselves, grow crops to sell, and be on the road to a better economic life.

But first, the disease that saps their sight and strength and drives them from these valleys to poorer land, first it must be controlled. And that will not be easy.

There is only one doctor here for about every ninety-three thousand people and there are too few clinics like this one, where infected people can be treated. A small skin biopsy is the best method of diagnosis. Under a low power microscope, the disease bearing larva can be identified at an early stage. The use of this equipment is efficient, the results more accurate.

Unfortunately, people must travel a long way to the clinic and then wait, wait for some word that their disease can be arrested, wait to hear that, maybe, some sight can be saved.

For many it is a frightening experience. As they wait, they cannot forget that the disease they bear is hard to cure.

Two drugs are available today for treating river blindness. And both must be administered in clinics or hospitals under the supervision of a doctor. While both drugs kill the worm, both also have unpleasant side effects. One causes toxic reactions. The other brings on a wild itching. The side effects require the constant presence of trained personnel; a simpler cure must be found.

MAN: We must be able to get a good drug which will not give the patients any reaction so that they would be taking their drugs. The other aspect, too, we need so much campaign and it's going to take us so long, dating probably more than twenty years to be able to eradicate this.

MOYERS: There is only one effective way to control river blindness. And that is to kill the black fly that causes it. Insecticides have to be put in the river, upstream of the breeding place.

MAN: What we've been using here in the upper regions of Ghana is the DDT and the unfortunate situation is that we are getting so much DDT into our rivers, especially the Volta Lake and with time this is going to poison the fish life. Now we've stopped using the DDT and we hope that we are going to get another chemical which will be easily broken down.

MOYERS: Scientists have come up with an insecticide that will kill the larva of the fly, without harming other forms of plant or animal life. But to treat an entire region with its several major river systems and thousands of streams, is an enormous task. After the insecticide has been distributed, it must be kept under constant surveillance, in case the fly develops a resistance to it, or the chemicals upset the delicate web of nature and bring a Silent Spring to West Africa.

Helicopters are being used to carry the war against the fly to remote areas. During the rainy season, the foliage along the rivers thickens and hides countless streams and small rapids where the fly breeds. Rains wash out the roads and make it impossible to reach the breeding site by land. Yet every location must be hit. The black fly has an amazing flight range of up to one hundred miles and can easily return to lay more eggs.

Yet the fight can be won. We know now that river blindness can be controlled. There is proof here. In the village of Finnkolo in Mali. Once the people were leaving to escape the fly. An experimental program was begun and today the people are back. Tea plantations flourish and village life has resumed its natural rhythm.

The children go to school. They can be children again. Lessons, games in the schoolyard; time to be curious and mischievous take the place of growing old too soon, of having to provide for their families because their fathers are helpless.

MOYERS: There are still blind people here. But the battle against the plague is being The people of Finnkolo can see again to that day when blindness is rare and the rivers once more bring life.

Finnkolo is just one village among many in the Volta Region area. Hope for the whole region depends on an international effort that has been mounted by four different agencies: The Food and Agricultural Organization, the United Nations Development Program, the World Health Organization, and the World Bank. Each plays a different part from helping to control the disease, to treating the victim, to marshaling financial resources, to improving agricultural techniques.

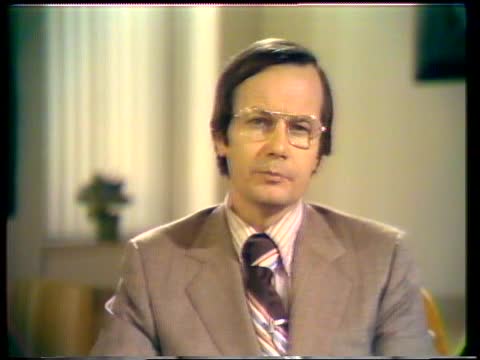

My guest this evening is the President of one of those organizations: of the World Bank. Robert McNamara

Mr. McNamara is former President of Ford Motor Company and Secretary of Defense under Lyndon Johnson and John F. Kennedy. The World Bank is the major, international institution in the world for making loans for development.

How did you get involved, you, the Bank, and you, personally in this project in the Upper Volta Region?

ROBERT MCNAMARA: In part it was accident. My wife and I were visiting Upper Volta. I try to visit the nations that are members of the Bank. There are a hundred and twenty-five of them. I've visited perhaps seventy-five or eighty-five at the present time. And while in Upper Volta, in Ouagadougou, the capital, I was told that this plague was destroying the, literally destroying the lives, the opportunity for economic advance and the actual life itself of tens of thousands of their people. And I was told that a research center examining the vector and the larva that were the cause of the plague was located within Upper Volta at a town called Bogadioloso. So I went there to see this and found three or four scientists that had dedicated major parts of their lives to determining the cause and possible remedy for this disease. In their eyes, the only thing that stood in the way of controlling it was lack of money and I think, perhaps, they were a little optimistic at the time. But that was their feeling.

MOYERS: Too optimistic. Why?

MCNAMARA: Well, I think that they felt that they had the answer in March of 1972. It's pretty clear now they didn't. But they were on the right track. They were designing new pesticides. They were designing new methods of applying the pesticides. And the project, we finally started; as a matter of fact, just last week, the helicopters began spraying the area, applying the pesticide, which, over a period of twenty years, we believe will control the vector sufficiently to allow the larva which exists in the human body to ultimately die. And a twenty year period is required for this, because these larvae live in a body seventeen years. And until the larva die, a resurgence of flies will allow them to transfer the larva from one body to another body and allow the whole disease to expand again.

So the essence of the program is to kill the flies they grow in running water; we’re flying pesticides by the air to the running water, to kill the flies. And as soon as that has reached the point where the fertile valleys, the White Volta, the Red Volta, the Black Volta valleys are reasonably clear of flies, people can move back to the fertile farm areas that they're forced out of by this disease, become productive, provide their own livelihood; it's a vision of hope.

MOYERS: Well, now, when you say the unproductive poor, whom do you mean? Who are the poor?

MCNAMARA: Right. Let me tell you just briefly about the bank. It's an amazing institution, created at Bretton Woods at the same time the International Monetary Fund was created, after World War II, 1946; it's owned by a hundred and twenty-five nations. These hundred and twenty-five nations are represented in this building by twenty full time resident directors and twenty full time alternate directors. So the Bank is literally governed by them.

And the division of power if you will let me take just a second between the management of the bank on the one hand and the governing body on the other is very interesting. I can't present I can't approve any loan by myself. But the board can't consider any loan I don't present to them. And this was done to prevent logrolling so that one country can't say: well, if you approve a loan for me, Mr. Country, I'll approve a loan for you. It can't be done.

This institution is run on a hard-headed, economic basis. But what's our objective? Our objective is to help the two billion people that live in the one hundred developing countries that are members of this Bank.

MOYERS: Two billion?

MCNAMARA: Two billion people. Our objective is to help those two billion people help themselves. And we can only help them if we help them increase their productivity. Now, what kind of people are these?

One-third to one-half of them are malnourished. The average caloric intake, for example, is roughly two thousand calories day. Ours is fifty percent more. And it's becoming increasingly clear that malnourishment, itself, is a cause of lack of development.

We're now understanding that protein deficiency in the last part of pregnancy, the last third of pregnancy and the early years of life, literally restricted the development of the brain and individuals are denied the right to realize the potential of the genes they were born with. Malnutrition is number one. Number two. High infant mortality. Twenty percent of the children die before they're five years old. Low life expectancy. Our life expectancy is twenty years more than theirs. They're literally condemned to an early death at birth. High illiteracy, roughly eight hundred million illiterates out of these two billion. years ago. The percentage of illiteracy has dropped.

A hundred million more than twenty But the population increase has been so great that the number has increased. High unemployment. We're concerned about eight percent in this country. Rightly so. They have twenty to twenty-five. This is the universe we deal with.

MOYERS: When you reported to the World Bank Governors you said the situation of many of these people is desperate. Has anything been done? Last fall, I think it was Is it still desperate?

MCNAMARA: Roughly eight hundred million of this two billion live, if you can call it that, on about thirty cents per day.

MOYERS: But where do you find them mostly? What countries?

MCNAMARA: Bangladesh is an illustration. Seventy-five million people in Bangladesh living in fifty thousand square miles. Now, fifty thousand square miles is the area of the state of Florida. Seventy-five million people living in the state of Florida; alternatively Bangladesh is -- two-thirds of it is flooded about six months of the year and the remaining six months, it's dry.

MOYERS: Well, about a year ago, in fact, as recently as a year ago, we were talking about the "Third World." This was a term that was commonly used around the world. Now, everybody's talking about the "Fourth World." Are these the people you're talking about?

MCNAMARA: The Fourth World, you might say, consists of the, perhaps, eight hundred million to a billion people who have average incomes of less than two hundred dollars per capita. And that consists of Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, the Sahelian zone, I was talking about earlier, Upper Volta, Mali, Niger; many of the countries of French West Africa; Mauretania, for example; Senegal; among East Africa: Kenya, Tanzania. That's the Fourth World.

If by that, you mean countries within kind of a roughly two hundred dollars per capita, per person, it's very difficult for us to understand what that means. Our income per capita on a comparable basis is on the order of five thousand dollars.

MOYERS: As I travel and as we all read, I'm encountering more and more of the question, well, is it worth it, trying to save these people? It's time, isn't it -- the argument goes -- to be somewhat unsqueamishly self-interested. That is: there aren't enough resources in the world to really save countries like Bangladesh. There aren't enough resources to make a marginal difference. So the best thing to do is to simply save those that have some capacity to cope and survive and let the others regrettably go down the drain. How do you feel about that?

MCNAMARA: Well, I read exactly the same argument two or three weeks ago in the magazine section in the New York Times. It was labeled Triage and they used the illustration of the wounded after World War One, when or during World War One, when the medical services weren't sufficient to take care of all, they divided in groups. One group didn't need it. Another group needed it, but there wasn't enough to take care of them. They let them die. The third group needed it, and they applied the medical service.

You can't deal with nations that way. They won't die. You can't bury them. They're there. That's number one. The second point they made was, it's like a lifeboat. You've got a lifeboat. The capacity's a hundred. You've got a hundred and twenty-five people in If we don't quickly throw overboard twenty-five, let them die, kill them, everyone of the hundred and twenty-five will die.

It's morally repulsive and it's technically wrong. If you want to use a lifeboat analogy, the lifeboat's capacity is a hundred and we've only got seventy-five in it.

MOYERS: But you are being moral and sentimental and these critics say that this is not the time to be moral and sentimental.

MCNAMARA: I believe in being both moral and practical. I don't think I'm sentimental. My point on the analogy of the lifeboat is that it's technically wrong. The lifeboat isn't full. The world capacity is not being utilized. I don't care whether it's food, or what it is you're talking about. We have a capacity to expand production in the countries that need it, in the Indias, Bangladeshes, and elsewhere, to expand production -- to expand production to begin to deal with these problems.

MOYERS: What about the argument, though, that nature is self-regulating, nature has its own limits. A rising death rate will compensate for the adversities brought on by rising birth rate and that the more we try to tamper with this system, the more, actually, in the long run, we're going to create misery.

MCNAMARA: Well, I'm not sure we know the linkages.

There are clearly linkages. But I think they might even be the reverse of just that argument. If we let more people die, it'll reduce births: I rather doubt that.

It's interesting that in India, and my statistics may be slightly off because they're from memory but it illustrates the point it's interesting that in India, the actual number of births per woman is on the order of six point five. The number of births per woman required to have a high probability that a male will survive to the later years in life of the parents is on the order of six point six or seven.

Now, I don't think that's coincidental. I think it's the high mortality of Indian interests that is driving up that fertility rate and therefore and so does the government by the way

and therefore the Indian government has asked us to work with them to develop a population project that will experiment with this. So we, in two districts in India, each with populations of more than ten million -- we have a population project which is trying out a large number of actions designed to reduce the fertility rate -- one of the actions is to change the nutrition by increasing the nutrition to try to reduce infant mortality to see whether that will stimulate a reduction in fertility. We're almost certain it will.

MOYERS: Your enthusiasm is, of course, contagious. But I remember right after World War II, the general belief in this country was that with enough capital and enough technology we could rescue the poor of the world from their poverty. And look as it today.

MCNAMARA: Well, I think we can. But we can't do it over night. In the last twenty-five years, the poor of the world, many of the poor of the world have been rescued. It's hard to get a single measure of development. But I suspect that the best single measure is life expectancy. That's the end of us all.

MOYERS: You mean the number of years you expect to live?

MCNAMARA: The number of years you expect to live.

MOYERS: Are people going to die before these problems are resolved?

MCNAMARA: Definitely. No question about it. They're dying now.

I read a report a few weeks ago I don't know how accurate it is, that a hundred thousand have died in Ethiopia because of starvation in the last several months. I read reports from the Red Cross that said this was a few months ago that a million in the Sahelian zone of Africa were on the verge of starvation. I know thousands have died in Bangladesh and India in the last year or so.

MOYERS: So you think that the term you used last fall - 'desperate' used the term 'appalling' still is true in many and you also

MCNAMARA: No question about it. And tens of thousands, probably hundreds of thousands are going to die in the next five or ten years because of neglect. Neglect by their own governments and neglect by the governments of the western world, including Japan.

MOYERS: And what is this going to do to the psychological attitude of the world?

MCNAMARA: In the short run, not much. Because people have been dying from neglect by their own governments or other governments for centuries. And, as I indicated, the life expectancy of these people is rising. Their condition is actually getting better.

It's very hard to believe that when you see the terrible misery that exists in these cities.

As I move around I never come back from a visit to one of these Fourth World countries without feeling depressed.

But the conditions are better today than they were. And they will be better in the future. But the rate of advance is not yet optimal.

MOYERS: Shouldn't you tie your assistance to hard, tough programs of population stabilization?

MCNAMARA: Well, perhaps we should if we knew what those were, but we don't. doesn't yet know what the linkage is between fertility reduction on the one hand to call it economic advance economic and social advance on the other. I think it's becoming increasingly clear that there are linkages. It's not just a question of practicing the rhythm method or accepting contraceptives. It's a problem of motivation. And how do you motivate a family to want to have a lesser number of children?

Using India as an example, there are a hundred million couples in India of which the wife is in the fertile range. A hundred million. And those hundred million couples must be persuaded that it's in their interest to do certain things they haven't been doing. То persuade them of that, there are forty or fifty thousand people in India dedicated to that job, employed by the government or governments to do that. It's a tremendous administrative problem.

Beyond that, it's not clear whether primary education for females will have more impact on their motivations than cheap contraceptives. So one doesn't really know exactly how to do that.

Beyond that, I should hasten to add, even if we did know, we don't have power to order sovereign nations to follow policies other than those that they're willing to adopt.

MOYERS: At the recent World Food Conference, there was considerable talk that among the newly developed nations that family planning is not to repeat your point, necessarily a cure for poverty. And they were constantly pointing to China. China's population has swollen tremendously. And yet there's no famine in China. Do you think that China is the model for development in these countries?

MCNAMARA: Well, let me say, first, I've never been to the Peoples Republic since it was the Peoples Republic. I'm not an authority on it. I don't think we in the Western World have a sufficient knowledge to come to firm conclusions.

MOYERS: But isn't the fact that the other countries..

MCNAMARA: Let me just say this. That there's ample evidence my wife was in China a year and a half ago and from what she said and others have said, there's ample evidence that the Chinese have adopted a population planning program. They do have barefoot doctors. The barefoot doctors do educate the people on the desirability of reducing fertility. They raised the marriage age. They've taken a number of very important steps. They've increased nutrition. They have equalized the distribution of food. They have reduced illiteracy. They have I should say, raised the role of women. All of this is very important in reducing fertility rates. So my impression and it's only an impression, rather than a final judgment -- my impression is they've gone far to effectively reduce fertility rates.

MOYERS: Do you think the attitude that was expressed by some people at the World Food Conference, that family planning isn't a cure for poverty is going to make harder the kind of programs you were talking about earlier?

MCNAMARA: No. No. I don't think so. The--it was expressed more fully at Bucharest at the Population Conference than it was at the Food Conference in Rome. And there, the Third and Fourth World were trying to demonstrate their need for additional external assistance. And they therefore, I think exaggerated the relationship between development measured in terms of economic per capita income on the one hand and fertility on the other.

My own impression is that we must increase the exposure of females to primary education. We must improve the nutritional levels. We must raise the health levels before we can achieve optimum fertility rates. But we need not expect Bangladesh to reach a U.S. per capita income level before their present three point five percent growth rate of population is cut to a more reasonable level - such as one percent.

MOYERS: My wife is going to watch this show. And she's going to say: He's singled out women and exposing them to the need for family planning techniques. What about men?

MCNAMARA: Well, certainly men too. And most effective programs of family planning involve both the man and the wife. I mention women because women are discriminated against in many countries of the world, not just perhaps the U.S., as some of them think they are but it certainly in the developing countries and particularly in education.

If you look at the rates of school attendance as a percentage of the primary age groups, you'll find that in many countries, only eight percent of the females will be attending primary age school, whereas perhaps thirty percent of the males will. It just shows the degree of discrimination. And there's ample evidence to show that as the literacy level of females is raised, their -- it affects their desired for numbers of children.

MOYERS: Let me share with you an attitude that I think rather common around the country; at least, it's been mentioned to me rather frequently of late. It's a we are suffering the highest inflation rate of increase in the cost of living in this country in years.

More people are out of work today than ever before. Our growth rate is slowing down dramatically. Don't expect us to help. We can't do it anymore. Mr. McNamara makes fine statements about what needs to be done. He diagnoses the problem explicitly and eloquently. But don't ask us to help. We have our own problems. What's your answer to that?

MCNAMARA: It's worse than they expressed it if that's the way they express it, because not only has the growth declined, there's been an actual setback. And the real income per capita in the U.S. today is probably five percent less than it was a year ago. So how do we go to a person whose real income per capita has decreased and ask them to, first support the existing programs, and secondly, support an expanded program.

Well, I think one approaches it on perhaps two or three grounds. First, he must understand how he's had a setback -- it's temporary; and it's a setback in a strongly rising trend. The real income per capita of the average income has increased about a hundred percent in the last twenty-five years since the start of the Marshall Plan, as a matter of fact.

And I don't care how you measure it. Meat consumption per capita is up a hundred percent.

Second cars, third TVs, the percentage of our children that are going to college, the security of the elderly, the life expectancy, the health, the equity and the health distributions. Anyway you want to measure it, the real income per capita in this country has increased dramatically.

Therefore, our capacity to help others has increased. Now, twenty-five years ago, when we had a real income per capita, perhaps half what it is today, our nation initiated the Marshall Plan, that program of help to Western Europe. Western Europe's strong today, in part, because of that Marshall Plan. At that time, we had half the real income per capita. But our economic assistance at the time of the Marshall Plan twenty-five years ago in relation to the income was ten times greater than it is today.

MOYERS: But today you do have something called the Age of Scarcity. And a lot of people are saying we can only help other countries if we're willing to give up something ourselves and quite frankly, we're not willing to do that.

MCNAMARA: I think it's correct. This is a choice. We can't consume all we're consuming and also add to the help we give other countries.

MOYERS: And you're saying..

MCNAMARA: But it's a choice that it's within our capability to make, particularly when one recognizes the amounts are so small. I was interested in a poll, I noticed the other day; it had asked American people: what percent of the government's budget was dedicated to economic assistance. And they said: ten percent. Now, the error is just tenfold. one percent. Not ten percent.

But the next question was: in the light of your answer, i.e., ten percent of the budget goes to economic assistance, do you believe that we should continue economic assistance. The answer was: Yes.

Sixty-five percent of the people said that they would believe that ten percent of the budget should go to economic assistance when only one percent goes.

MOYERS: What's your conclusion from this?

MCNAMARA: The conclusion I've come to is that there's an underlying support for economic assistance and that support is based on a moral feeling as well as a feeling that it's in their self-interest to do it. And we can talk about that if you wish. So that's the first point I come to.

The second point I want to draw from it is that the amount of additional assistance required to reach what I'll call optimum levels, however you wish to define it, five or ten years from now, is very small in relation to our income. And it can be attained over the next decade by dedicating just a small percentage of the gain that we will achieve in that period. In real terms, I'd say two to three percent of the gain in real income, if diverted to the developing countries would make the difference between misery and a good life.

MOYERS: Are you saying that we can help without giving up anything?

MCNAMARA: We cannot help without giving up something. But the amount we have to give up is very small and it's out of a tremendously bountiful life.

MOYERS: Why shouldn't the oil producing countries take on the burden of this task? They have all this new found cash.

MCNAMARA: Well, of course, the answer is, whether they should or not, they are. And this is very interesting...

MOYERS: They are...

MCNAMARA: They are. A tremendous amount of economic assistance has been committed.

MOYERS: How much?

MCNAMARA: Well, it's a little difficult to be absolutely sure but it exceeds ten billion dollars.

MOYERS: From the oil producing..

MCNAMARA: From the oil producing...

MOYERS: To the Fourth World.

MCNAMARA:

That includes the Third and Fourth World. Within the past twelve months. Ten billion dollars. Now, they've just newly received this huge flow of foreign exchange. They haven't yet had time to develop their own, long term programs of development but out of that, they have diverted, committed ten billion dollars or more actually the figures we have are twelve and a half or something like that - to the developing world. And of that, they've disbursed two billion...

MOYERS: Can we step back because of what they're doing?

MCNAMARA: Whether that's enough or not, who can say? We have cut back. That's the tragic thing. The economic assistance of the Western World, Western Europe, U.S., Canada, Japan in real terms has decreased. It hasn't kept track, it hasn't kept pace with inflation and as a percentage of our income, it's declined dramatically. At the time of the Marshall Plan, two and a half percent of our gross national product went for economic assistance. Today, it's just a tenth of that: point two five.

MOYERS: You think this is the result of insularity, of retreating?

MCNAMARA: It's the result of frustration; yes, it is an insularity and it is a retreat and it's been more noticeable the last year or two. I think that's to be expected.

MCNAMARA: Well, we have - as I say, in this country, we've had an increase in real income of a hundred percent, in twenty-five years. Now, what's it represented by? Automobiles, some of them bought on time, credit; much improved housing; much of it mortgaged; increased participation by our children in colleges, some on a credit basis; and when income declines five percent, it's very difficult to adjust that consumption pattern five percent. Not that the consumption pattern doesn't have a third tv set or a second automobile or a vacation home that could be taken out of it but it's very difficult to take it out after you've bought it and it's on mortgage payments.

MOYERS: So you say, they feel frustrated?

MCNAMARA: So they feel frustrated. And there's a malaise. And I think the malaise is the result of this sense of frustration. It's a result of an expectation gap, rather than lack of progress. And we fail to distinguish between these two. We set our hopes higher than we were capable of realizing. And then when we didn't realize them, we became disappointed and frustrated. And, in a sense, ineffective.

MOYERS: Is there a paradox in the fact that part of the problem these countries face is the result of an increase in fuel prices, which goes into fertilizer and other projects? That the Arab and oil producing countries are coming in to give them help, in a sense to subsidize the price of that oil and we are, if we increase our help, we're having to increase our help, in effect, to subsidize the wealth of the oil producing countries. Isn't that a paradox?

MCNAMARA: The economic assistance - if we increase it, which we haven't, but I hope we will, it would not go to subsidize the transfer of oil. The oil price increase occurred at a time when several other major changes in the world economy were adversely affecting the developing countries and it's this package of problems that has to be dealt with. The oil price is only one of them.

MOYERS: What are the other two or three?

MCNAMARA: The others are drought conditions in much of Asia and part of Africa, which led to food scarcities, serious food shortages and rising food prices. Dramatic increases in prices in the industrialized world because of prosperity. The rates of development, the rates of economic advance in Western Europe, Japan, North America, in 1971, -2 and -3 were among the highest on record. This strained the production system. Demand put pressure on supply. This tended to stimulate the price increase. That's been the major reason for worldwide inflation.

As that occurred, governments tried to take action to correct it. The action's led to recession. As the recession occurred, the export market of these developing countries began to shrink; and they depend on exports for foreign exchange, to pay for their imports; imports they need for more fertilizer, more irrigation, a foundation for their economic advance. So that occurred.

At the same time, their terms of trade began to deteriorate. It simply means the price of their imports went up more rapidly than the prices of their exports. combination of these several things: the increase in the price of oil, the shortage of food and rising prices of food imports, the reduction in their export markets, and the deterioration of terms of trade; it's that package of adversity that we have to try to help them deal with.

MOYERS: All of this comes down to a feeling not unlike that of a man who said to me recently in Dallas: I woke up one morning and the world that I knew: the known and the tried and the identifiable world, financially, was gone.

What happened to that? I think you've said something about what happened to it. But then the question becomes, even though the technical terms are beyond most people, including me: is the world developing now monetary and financial structures to deal with this strange new world that has suddenly emerged?

MCNAMARA: Yes. I think that that's part of our responsibility and we're trying to help in that. And the events of the last two or three weeks should be a cause of optimism for your Dallas friend because the finance ministers of the world, the governors of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank met here in Washington to consider this problem. And they took several actions to begin to deal with the financial problem.

MOYERS: In layman's terms, what do they mean?

MCNAMARA: Well, the first problem is that caused by the fact that the oil that we're buying, we can't pay for in goods today because the oil producers lack the capacity to absorb the goods. In a sense, that's good, because if we don't pay for it in goods,

We're paying for the oil, in part, with paper. And we pass the paper over to the oil producers. And then that paper must circulate through the world, evenly, so that they'll take the Bangladesh paper and Italy Italian paper and the paper from Great Britain and all nations equally and if that paper stops circulating, then we have a serious disruption in the world economy. There was danger that the paper would stop circulating, the risks of standing behind it were getting greater than the commercial banking system of the world could accept, and it was necessary for governments to agree to begin to accept some of those risks. That's essentially what was done.

Last week and the week before, the finance ministers agreed to set up two funds, one known as the Safety Net Fund that Secretary Kissinger had promised and was to be set up by the OECD nations and the other, known as the Oil Facility of the International Monetary Fund, which is to be set up by all the nations that are members of that. And these two funds will help assure that these pieces of paper continue to flow evenly and help assure, therefore, that there is no serious distortion of the economies of these consuming nations, caused by a failure of the paper to flow evenly during the next year.

Similarly, these finance ministers approved the expanded bank, World Bank Lending Program. We borrow from OPEC, we put those funds to work in the developing countries. This is another form of what's known as recycling, all designed to minimize the impact of this oil price increase. Ultimately the world will have to adjust to it. They'll have to adjust to the oil price increase by transferring goods to the oil producers.

MOYERS: Are you saying inflation is here to stay as a worldwide phenomenon?

MCNAMARA: No. No. I'm just talking about adjusting to the oil price increase by paying for it in real terms. And that's going to have to be done in goods. And when done, it's a real penalty. There's no it's you can't close your eyes to it.

MOYERS: Who pays the penalty?

MCNAMARA: All of us. All the oil consumers pay it. But the amount of the penalty is absorbable within our society. It might amount to two to three percent of one year's income and we can absorb that. We need not allow this to disrupt the societies of the industrialized nations and we should not allow it to disrupt the societies of the developing nations. And I'm not arguing whether it's right or wrong.

MOYERS: But you are saying some structure is emerging that will give some consistency to the world?

MCNAMARA: Exactly. Some structure is emerging which will allow the world to adjust over a period of time to this price, assuming the price continues.

MOYERS: You've been in this job now six years. You have the image to many people of the modern manager: Harvard Business School, Ford Motor Company, Secretary of Defense for seven to eight years. Have you learned anything at the World Bank that would startle or scare your old friends about the nature of the world economy?

MCNAMARA: Well, I'll tell you one thing I've learned. I've learned my wife was right. She pointed out to me four or five years ago a passage from T.S. Eliot, which I haven't forgotten since then and he wrote, and I think it was in his Fourth Quartet, he wrote these lines: We shall not cease from exploring and at the end of our exploration we will return to where we started and know the place for the first time. And I think that my service with the World Bank is part of this journey of exploration. And it's tremendously expanded my understanding of nations and peoples.

MOYERS: Does it say anything to you about the need to radically change the way things are and do you think the assumptions on which we've lived in a capitalist society for so long have to be tackled and altered? I mean

MCNAMARA: Well, we're changing our assumptions. I don't think the program allows time perhaps to go into it fully. But we are changing our assumptions. We're becoming much more sensitive to the rest of the world. We -- it is true that in this present period of difficulty, economic difficulty in the U.S., we tend to be turning inward. But that's just a minor dip in a rising secular trend of turning outward. Certainly, in your lifetime, and surely in mine, this nation has become much more sensitive to problems elsewhere in the world, much more willing to try to join in meeting those problems. I think we've learned we can't do it all by ourselves and we shouldn't try but we're understanding that on our own, narrow self-interest, we should deal with these problems. Our children cannot live on an island of affluence in a sea of poverty. That's not a secure world. It's not going to be a prosperous world for them. It's not going to be a happy world for them. We can only live if we take account of the problems of other nations. I think that philosophical, political, economic change is occurring.

MOYERS: What I was getting at in particular is, that if you take the Bank where I think and others think you seem to be taking it, you're going to go right into the heart of some of the most difficult questions we face in the world the redistribution of income and wealth taking it from here and giving it to here -- and land reform. And every time you get into land reform in many countries, the ruling class says: wait a minute. Not here. Isn't that going to cause you some consternation?

MCNAMARA: It has and it will. And it will cause my successor difficulty. Most of all, it'll cause the governments of the developing countries difficulties as it is causing the U.S. government difficulty. Our argument today, in the U.S. Congress and between the Congress and the Administration is exactly on that point: how is the burden of sacrifice going to be distributed? That's the essence of the problem. And we face that every day in every one of these developing countries. We're just beginning to understand ourselves the depth of the problem and some of the actions that need to be taken to solve it.

The income distribution in the developing countries, in general, is more unequal than it is in the developed countries. There are many, many developing countries in which the top twenty percent of income receivers have incomes twenty times the level of the bottom twenty percent. A comparable ratio in the Western World is eight to one, not twenty to one. So there are greater income distortions there than here. This simply reflects the maldistribution of political and economic power.

MOYERS: Power.

MCNAMARA: Exactly. And as you suggest, over time, to begin to deal with the problem, to do what I think must be done, which is to increase the productivity of the low productivity elements in those societies, that's the only

MOYERS: The landless poor, the farmers

MCNAMARA: The landless poor- exactly. Roughly, what we call the lowest forty percent. The only way to deal with the lowest forty percent is to raise their productivity; redistribution of income is not going to do it. But, to raise the productivity, there has to be a redistribution of government services. You've got to stop treating the urban centers as privileged centers for purposes of primary education and get that primary education down to the rural areas. You've got to have roads out there. I think I'm right in saying that fifty percent of the rural people in Ethiopia are more than one day's walk from the nearest dirt road. Now, how can you expect them to increase their productivity and produce a surplus for cash sale, which they may then use to build a better house or buy a school or something, when they can't get their product to market?

But throughout the developing world, there's a maldistribution of services. Education, health, water, et cetera. That's got to be changed. It's going to take time to do it. The political power is in the hands of those who don't want to give it up.

MOYERS: Well, that's the nature of power is not to yield. And aren't you flying in

the face of nature?

MCNAMARA: Yes. Surely. But, of course, that's the story of civilization. And that's been the history of power in the industrialized countries. It certainly happened here. Look at the income tax. That was fought. That's been a shift of economic power. Look at our look what's happened in the U.S. Congress in the last several weeks. That's a shift of power. This is all part of the process to begin to deal with some of these inequalities. I think the world has made great progress in dealing with them. But, my God, it's an imperfect world and I'm afraid it's going to be so for thousands of years to come.

MOYERS: One final question. When you come into confrontation with these facts of nature, with power, with the disparities in incomes, when, as you have done, you see the faces of these eight hundred million people who are living in what you call desperate conditions, what is there that makes you not simply want to chuck it all and go lead a more serene life?

MCNAMARA: Well, hope, I guess; first, a realization that progress has been made and sometimes I forget that and I have to go back and read the story to really refresh my mind and see that there is a basis for hope. Because all we really need to do is extend the trend of the past; the last twenty-five years has seen tremendous advances. There's wide-spread misery today. But much less today than there was twenty-five years ago. I can remember it in part myself, a little over twenty-five years ago, I was in the U.S. Air Force in India and the time I was in Calcutta, there were ten thousand dead bodies on the streets of Calcutta. They weren't dying by the thousands. They were dying by the hundreds of thousands in India at that time. That was the terrible famine of 1943. We haven't had that today. We need not have it tomorrow. And it's a hope to avoid it that I think underlies our work.

MOYERS: On that note I want to thank you for spending this hour with public television.

I've been talking with Robert McNamara, the President of the World Bank.

Until next week, good night.

- Episode Number

- 104

- Contributing Organization

- Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group (New York, New York)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip-68b7db9ace9

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip-68b7db9ace9).

- Description

- Episode Description

- World Bank President Robert McNamara discusses the challenges of negotiating economic and political relations between developing countries and industrial nations. The episode also previews a World Bank film, A PLAGUE UPON THE LAND.

- Series Description

- BILL MOYERS JOURNAL: INTERNATIONAL REPORT looks at foreign affairs through a Washington lens. Interviews include: Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, Chancellor Helmut Schmidt of West Germany, World Bank President Robert McNamara, former Secretary of Defense Clark Clifford as well as journalists, European political advisors, academics and other experts on American foreign policy.

- Broadcast Date

- 1975-02-06

- Asset type

- Episode

- Genres

- Talk Show

- Rights

- Copyright Holder: WNET

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:58:17;28

- Credits

-

-

Editor: Sameth, Jack

Editor: Moyers, Bill

Executive Producer: Sides, Patricia

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group

Identifier: cpb-aacip-133b9f3a503 (Filename)

Format: LTO-5

-

Public Affairs Television

Identifier: cpb-aacip-af3c65613e3 (Filename)

Format: U-matic

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “Bill Moyers Journal: International Report; 104; A Report from Africa and a Conversation with Robert McNamara,” 1975-02-06, Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed December 15, 2025, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-68b7db9ace9.

- MLA: “Bill Moyers Journal: International Report; 104; A Report from Africa and a Conversation with Robert McNamara.” 1975-02-06. Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. December 15, 2025. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-68b7db9ace9>.

- APA: Bill Moyers Journal: International Report; 104; A Report from Africa and a Conversation with Robert McNamara. Boston, MA: Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-68b7db9ace9

- Supplemental Materials