Bill Moyers Journal; 312; A Conversation with Robert Penn Warren

- Transcript

ROBERT PENN WARREN: I'm in love with America, that's funny right? I really am. I've been in every state of the union except one, and I'm going there within a month, BILL MOYERS: Which state is that? WARREN: That's Oregon. And I've traveled in the Depression and the $50 car, broken down all green Studebaker. maker. I want all over the West. I spent time on ranches here and ranches there, and I've been all sorts of places. And I've had money, change, giving them back to me for gas in the Depression. Some guys say, oh, keep the change, buddy you look worse than I do. I have a really, really fell in love with this country. BILL MOYERS: He is a rarity in American letters.

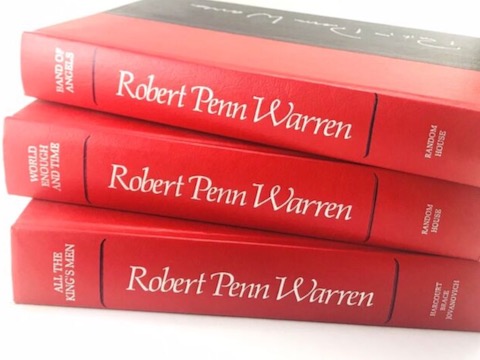

The only writer to win Pulitzer Prizes for both fiction and poetry. And he loves the country he often rebukes. We'll see why tonight in a conversation with Robert Penn Warren. I'm Bill Moyers. (ALL THE KINGS MEN TRAILER) The Pulitzer Prize novel becomes a vital, very great motion picture. MOYERS: The novel became a classic when Robert Penn Warren wrote it at the age of 41.

Almost three million copies have been sold around the world in 20 languages. The movie became a classic too. It won three Oscars. Its subject was politics. Its theme. Corruption. SCENE FROM MOVIE: No, we won't stop seeing each other, will we? No. Willie's got big ideas, Jack. What do you mean? A girl like Jack could be a governor's wife or even a president? What are you talking about? He ditched Lucy. He ditched me and he'll ditch you. He ditched me. ANNOUNCER: All the fascinating characters from the novel come alive. Adam Stanton who believed in his sister's honor and Sugar-Boy. with that 38 under his arm hit. (FILM)Now listen to me, your hicks. Yeah, you're hicks too. They fooled you a thousand times just like they fooled me. I'm going to stay in this race. I'm on my own and I'm out for blood. WARREN: You sort of grew out of circumstances?

It grew out of the folklore of the moment where I was. And I guess also because I was teaching Shakespeare, reading Machiavelli, and William James. All the things flowed together. MOVIE: There's no God but Willie Stark. I'm his prophet and yours. Gamblers and crooks fought for his favor. WARREN: That was a world of melodrama. That was a world of melodrama, a little pure melodrama. Nothing like it, since, until Watergate. And he was. Boy, it's melodrama, so you think what? MOYERS;You think Watergate was melodrama, right? WARREN:Obviously it was melodrama. MOYERS: Not tragedy. WARREN: Not tragedy. It's not tragedy. It's a tragedy, too. But it was melodrama. You couldn't believe it. It was happening to be true. MOYERS: Did you think that All the King's Men would become a classic? WARREN: I never gave it a thought.

I just, I tried to make an honest living. MOYERS: It has been a prolific life since Robert Penn Warren arrived in Guthrie, Kentucky. Seventy-one years ago, this month, since then he's been almost everywhere and written just about everything, nine novels, ten volumes of poetry, short stories, essays, two studies of race relations. There's hardly an award he hasn't collected, the National Book Award, the chair of poetry at the Library of Congress, the Bollingen Prize, the National Medal for Literature, and of course, those two Pulitzers. He's still writing, increasingly intrigued by the fate of democracy in a world of technology. We talked at Yale University, his base for writing and teaching this past quarter century. MOYERS: As a poet and a novelist, as opposed to being the author of All the King's Men, how do you explain the vast disenchantment of our modern times? WARREN: I don't know. It's touched every country in the world.

We're not alone, it's part of the modern world. MOYERS: Is there something in it? There's something in the modern world going on, and I don't profess to understand it. We can make guesses about it. MOYERS: Make some guesses. WARREN: Well, we are for one thing, the whole Western world is undergoing some deep change in its very nature. It can't believe in, and one of those things is clearly how the democracy can function in a world of technology. That's one thing, and other things just seem to be the massive number of people involved. How does government design the modern liberal democracy design to function within a certain limited world? MOYERS: How successful do you think we are in keeping some notion of democracy and some concept of the self-alive in a highly technological, scientific age of huge organizations? WARREN: Not successful enough.

You can see many indications of that. MOYERS: What are some of the manifestations you see that deeply trouble you? WARREN: Now, this is a small academic matter in one sense, the death of history. MOYERS: The death of history? WARREN: Yes. History departments are, I'll believe, TKTKTKT, I'm told, I don't know, but statistics. But certainly, the sense of the past is passing out of the clutches of a generation. MOYERS: What do you think will be the consequence of that? WARREN: I don't know how you can have a future without a sense of the past, a real future. And we have a book like Plumb's book, The Death of the Past, which is a very impressive and disturbing book. As Plumb puts it, in the past, people have tried to learn what wisdom they could from history. They have tried to learn from what has happened before.

Now he says, social science will take the place of history. The past will die and the machine will take over, done by social scientists. That's his prediction. He says, only history keeps it alive, the human sense, history in the broadest sense of the word, like literary history or political history or any other kind of history. It's man's long effort to be human. And as a student understands this, penetrates this problem. He becomes human. If he wants to give that up as a concern, he turns to mechanism. MOYERS: The machine, the process. WARREN: Some process to take charge. He may have the very kinds of machines, the many kinds of processes he can turn to. But the sense of the human being's effort to be human and to somehow develop this humanity

that is what history is about. MOYERS: Do you sense among the students you teach and among the young people you know, this loss of the past, this disconnection from history? WARREN: Yes. I have. I have indeed. MOYERS: What it is the effect of it? WARREN: It's a certain kind of blackness, certain kind of blackness. But the past is dead for a great number of young people. It just doesn't exist. MOYERS: I know you once wrote that Americans felt liberated from time and that it gave them a sense of being, gave us a sense of being on a great gravy train with the first class ticket. WARREN: Well we had the country of the future, the party of the future.

We had the future ahead of us and we had this vast space behind us -- this continent. We had time and space, we could change the limitations of the European world. Such a simple thing is a man's hands becoming valuable. A man on the American continent in the 18th century was valuable. Neighbours were valuable, hands were valuable, we would think for hands to do, and so the whole sense of a human value changed, beginning with the value of hands that they could do or the value of a neighbor down the road a mile away and instead 20 miles away. These things made a whole difference in the sense of life and it's a fundamental stimulus to our sense of our own destiny. MOYERS: They also were a powerful incentive where they're not to human dignity.

WARREN: Human dignity because the hands mean something. They're not just things owned by somebody else, they belong to that man and then all of the rest of the factors that enter the creation of the American spirit, all of those things are involved. MOYERS: You said what? WARREN: We had, we could always move and in the sense of time being time-bound and space-bound disappeared, but mitigated anyway, the whole psychology was born, never been in the world before. MOYERS: A very optimistic philosophy of progress. WARREN: As Jefferson said, in writing to his daughter Martha, he said, Americans, I think she's daughter Martha anyway, Americans fear nothing, you see, cannot be overcome by any application, you see, and that's the other word, ingenuity, ingenuity, that America assumes that they

are no insoluble problems. MOYERS: We've really been trapped in a sense by Thomas Jefferson's definitions of America in those terms. WARREN: That's right. We assume that we can solve anything rather easily and we're always right. We think we're usually right about it, because since we can solve things, we're the ones who are right. MOYERS: I remember you wrote once that America was defined by one man in an upstairs room, Thomas Jefferson writing, all men are created equal, giving this great metaphysical boost to the American self-image. WARREN: Yes, he gave, he gave us more than any one person gave us our self-image. I think he was wrong about human nature and his emphasis on it. He wasn't a fool of course. He knew that there were bad people, and he knew that there were stupid people because

of the other six I think siblings in his outfit of four had something wrong with him in the head. The other one died young, just as a genius, while the only one, of this brook of children, who was even, I think this is right now, who is not in some way deficient, and so he was probably a way out of the fact that all men are not born equal, right, they're at his own fireside. MOYERS: How do people who still live with that mystique of democracy, that mystique of the self? How do they come to terms with the world you have described as being large, impersonal, driven by science and technology? WARREN: They say that's the way to solve it. By knowledge. They say, somebody will fix it up, the expert will fix it up somewhere.

There's some that they'll be the magic counselor, they'll be this, they'll be that. The expert will come along and fix it up, and our faith has gone from God to the experts. And sometimes the experts don't work out. MOYERS: You've written a lot about how to hold on to the sense of self when the world is changing this way. What do you say when the forces are beating up on us from many directions, forces we can't understand, forces we can't change, forces we can't even define? How do you force them? WARREN: You know. Even more than change. We want our technology. We should have. We should want it. It's how we use it. It's important. It's an attitude toward it, it seems to me, it's important. It's presence, from scientific speculation to the applications and technology represents a great human achievement.

It's how we approach this and how we wish to use it. MOYERS: I wouldn't want to abandon, would you, this material progress we've made, the things that make life so much more amenable. WARREN: God, no, I don't want to abandon it. My grandfather said, he took a very dim view of the modern world. He was born in 38, 1838, and fought the Civil War and wound up life in 1819, 1919, 1920, I mean, like that, 21. He looked around the modern world and invited it not all to his taste, but he said they have got two things that make it worthwhile, fly screens, and painless dentistry. Well, I'm for fly screens and painless dentistry too. I want that, but I want some of the things to move. MOYERS: What is the proper posture or attitude from all the years you've lived?

WARREN: The problem is finally a human problem and not a technical problem. And we're back to the history again of the sense of the human as being the key sense. As you, we talked about education, this means it's so-called humanities, is the only place for students to find the point of reference for the application of their science and their technology. And the sense of the struggle to define values. MOYERS: What are the values that are most important to you now? WARREN: Well, I can tell you what my pleasures are. Think about it that way. Because I'm selfish and want to fill my days in the way that pleases me. So happens it my chief interest in life, aside from my friendly affections and family affections,

which is another thing, though they are related. In fact, I like knowledge and poems. And I want to read them and I want to write them. Because I have an occupation which, to me, I can go beyond that and I acquire that occupation. It's the only way I can try to make sense to myself of my own experience in this way. Otherwise, I feel at a loss in the rutTKTK my experience and experience that I was driving around me. This is a way of making your own life make sense to you. It's your way of trying to give shape to experience.

And the satisfaction of living is feeling you're living significantly. That doesn't it mean grandly. That means it has a meaning, it has a shape that your life is not being wasted, it isn't just being from this to that. MOYERS: It also means imposing... Understand it. An imposing order, doesn't it? WARREN: Order. Some sense of order. Yes. MOYERS: What does poetry and literature offer people in the age of technology and science? I say it offers an inward landscape. I mean, I've been talking about outer landscape. But it offers an inner landscape, it offers a sense of what man is like inside. The experience is like, he can see perspectives of experience.

This may be in poetry or maybe in history, it may be in political science. It may be in a historical perspective, man, the view of how he should go and himself over a period of time has changed. MOYERS: But how does it help us to see ways to deal with technology, with organization, with size? WARREN: It makes us ask the question, how that light, that object or this automobile, this plane, will serve deepest human needs, or there's the gadgets, but this is a toy. Now when Coleridge has the Ancient Mariner, shoots the albatross for no reason, except it has the crossbow of the shoots, the albatross. He's dealing with that problem. The problem is already there, you see, the machine defines the act. The man shoots the bird, only because he has a crossbow.

Why should he shoot the bird? He has no reason to shoot the bird, it's a gratuitous act. The machine defines the act, because the machine will do so and so, therefore it must be done. You see, what I'm getting at there, Coleridge's poem is a criticism of this man as victim of technology. MOYERS: How do we get control? WARREN: It's a constant struggle, and means are trying to inspect the things that shape us, make us. Once we understand it, we can sometimes do something about it. Now, I'm not talking a psychoanalysis, I'm talking much broader than psychoanalysis. This is one, is a special kind of the application of principle. It's always been functioning in the world. People look at what made their world tick or made them tick, and they achieve some sense of freedom from mechanical forces.

I mean, not from forces of machines, of mechanisms, but the forces that have made them into machines have given them habits of doing this thing this way and that way. Now, religious conversion is one of the most obvious examples of this. Reconversion? MOYERS: Religious conversion. WARREN: Religious conversion. It is an old fashioned way of looking at it. Man has been one kind of man, and he suddenly understands life differently. MOYERS: You believe that's still possible? WARREN: I think so. I think he can exist. It's just certain people. MOYERS: Well, give us some help. How do we do it? WARREN: Try to see how you came to be the way you are. The poem that Colerdige changed me, and it changed me, changed me. MOYERS: And you think it's still this part of the creative process? WARRNEN: It's I still believe in these things as a religious conversion. So I'm a non-believer, I'm a non-church-goer, but it's this way.

I'm in that rather common type, I think, now, of the yearner. MOYERS: The yearner? WARREN: The yearner. I would say that I have religious temperament, you see, with a scientific background. MOYERS: The Pilgrims sought God and looked for a promised land in the hereafter. What are you yearning for? WARREN: I yearned for significance, for life as significance. Now, if I'm fooling with the poem or a novel, I'm in a small way trying to do the same thing, and trying to make it make sense to me, that's all. That's the reason why I like teaching. I have a real passion for teaching. MOYERS: How's that? WARREN: I think there's nothing more exciting than seeing a young person moving toward the moment of recognizing significance in something, in the inner significance of something.

MOYERS: And it happens under what occasions? WARREN: It can happen in a classroom, it can happen in any classroom, anytime, and very often. Very often indeed, and I'm a parent, and I've seen it happen to my children. MOYERS: How does it happen in an urban, complicated, interdependent city, where life is crowded, services are poor, and a feeling that one is being acted upon by men and events over which he has no control? How does this yearning to signify, find the creative satisfaction? WARREN: It means a whole regeneration of the feeling of a society, and it's not going to be done by just making aTKTKTK peculiar appropriations. I knew one man, who I read this scene now, who used to live in this neighborhood, whose

job was to explain the background of the National Merit Scholarship winners, what could they find in common among these boys and girls who were spectacular intellectually, and had great drives? And he said he had worked on it for years. He found one thing only was in common, there was always a person behind that child. It might be a friend, or a teacher, or a old grandfather, who was illiterate, because I can deal with education, with some sense of a recognition by an older person of this child's worth, this child felt valuable, felt valued, and some one person, or maybe more than one, had made him feel this, was worth sitting at the night reading a study

his book. MOYERS: And you're saying somehow we have to get that personal touch back into it? WARREN: Some sense, something we're corresponded to that, to humanize education, or maybe you can't create the whole life again, maybe it's gone, I don't know. It hasn't had to be optimistic, but he said at least if there was anything, there was one person, or maybe more than one, behind that child, who suddenly seemed like a miracle. He might be coming out of some lonely, illiterate, starving, ranch, and Wyoming, and suddenly this child appears, and he looks like a miracle, but no, the old grandpa was there, talking to the child.

Some teacher spotted him. When Dreiser was the most unpromising boy, you can imagine, he was just totally unpromising. He was a ferocious masturbator, I tried to get a wealthy girl, got money and sex tied up, tying her all his life. He was a poor student, he scarcely read a book, but some schoolteacher of his field spotted him, and said, that boy has something, and she let him go and graduate from high school and he got a job in Chicago as a clerk in the basement of a hardware store, a stockboy. And she hunted him up a year or so later and said I'm going to send you to college, it's old maid, it's old maid schoolteacher, so I'll save them money and I'm going to send you to college. You've got something, send him to college for a year.

He wouldn't go back there, not get anything here, just not learning anything at all, so he wouldn't take up any of them, any boy, so I wasted your money. But that's the one person that put the finger on him, though, and says, you've got something. The only thing that will cultivate the sense of the value of the human being is the hope. Make that man feel valuable, make it easy for someone else to feel valuable. MOYERS: Well we've been for 200 years, a country that moved on more and better in progress, and that hasn't been all bad, it's had a big price, but the question it seems to me now is, how do you hold on to the material abundance, spread it around so that more people share in it, but at the same time keep what you've written about so often, that sense of self and dignity and individual responsibility.

WARREN: Also we've got quit lying to ourselves all the time. Now the Civil War was the biggest lie our the nation ever told itself, it's freed the slaves, that's what they do with them. The big lie was told, and we're full of virtue, we did it, we freed the slaves, and it came home with the roost 100 years later. But we lied to ourselves all the time. The lying about Vietnam was appalling. There was awful lot of lying about Vietnam. It was all kinds of lying, now the lying about, I didn't even Mexico for the very start. I absolutely believe, I'm not going to take, I'm not saying give it all, give California back to Mexico, although if you have to give it to something give California's in my tktkt though, but which I used to know very well, but the point is you cannot, you cannot, you can't keep lying to yourself indefinitely.

And my daughter, was studying a history lesson, American history several years ago, when she was a little girl in school, not now, she was a senior. But I was hearing her lesson for the examination. And she said something that was so appalling wrong, I must have flushed, she said, "Don't say anything daddy. Don't say anything poppy. Don't say anything, I know it's a lie, which I have to tell my teacher." Well that was sort of, this is the way half of our life is led in America. We have the right lies to tell ourselves. MOYERS: But haven't we stripped ourselves now that pretense, I think we were never innocent, but now the pretense is gone. The pretense is going anyway, you don't think it's all, I don't think it's all gone, no, you'll go here more lies the next six months and you've ever heard in your life before. MOYERS: The stuff of another novel. Well, you go here, the lies are going to be told, but see, I mean love with America,

it's funny, I really am. MOYERS: What do you like about it? What does America say to you affirmatively? WARREN: Well, the story is just god damn wonderful, I mean the whole thing, the whole thing, the little handful of man, you know, who pledged their lives in sacred order, and stood off the world. It's a great story, and just the plain sweat and pain they witnessed. And the integrity, incredible integrity, integrity. It's just lots of it, the people, the number of people, history is full of it. MOYERS: This is the man I'm talking to who wrote that piracy and go-getterism are part of this country.

WARREN: They are. But at the same time you find, the other thing is there too, but even the evil is part of the story. MOYERS: It's the story you love. WARREN: I love the story, but also it's the, you can't have a story like, you know, for babes and sucklings, all life is evil against good. And the American history is interesting because that's the way it is. MOYERS: And often the evil and the good reside in the same personality. WARREN: In the same personality. On one hand, a man like Houston is a pirate and a brigand, but the boy who will read Homer by the far side of a Cherokee chief when he's 13, 14 years old and say, "that's me." is pretty good. He ran away from home and was living with the Cherokees in East Tennessee when he was a boy of his teens and reading Homer and it turned out to be great.

MOYERS: Well, he was very lucky because when he headed west he stopped in Texas. WARREN: He stopped in Texas. He stopped in the right place at the right time. But he started out, he and the old Sable Indian chief met later on after he had been governor of Kentucky. I mean, Tennessee and it had some of the women there with his wife and his wife and left. And then they were the Indians again. He and the Indian chief planted the conquer the whole West, including Mexican West and Jackson stopped him. This is almost verifiable, but it's something doubt about it, but it's almost certainly true. And when he crossed the river, he plans to cross the river into Texas, his friend rode with him to the river and gave him a new razor, as a parting present, razors were hard to come by, and he turned around and said, this razor saved him -- sent him a president.

Well, now, this is America. I mean, I like those romantic stories of America and the incredible energy and the incredible humor of America. MOYERS: Humor? WARREN: Humor, the whole tale, the folk tales, incredible number of folk tales, incredible number of tales. The whole sense of the south, the old southwest, incredible. But it's the complexity of it that is engaging, but what I hate is that it destroys a complexity. It wants to wipe out all that past and see us outside of a past like that. We've had a heroic age that is heroic, is Homeric. MOYERS: Is it over?

WARREN: That's up to us. I felt a thrill with the moon shots. I know it's not very sophisticated, but I think that's not the whole story though, moon shots and poems are not very different. They are both totally irrelevant to their ordinary business of life. The guy that devotes life to a feeling with an laboratory or a feeling with a poem, they are both outside of the ordinary common sense world and they're both crazy. MOYERS: Yet you value them? WARREN: I value them indeed. I think if you want to get rid of the craziness in the world, you have nothing left. MOYERS: I remember in one poem you want to ask yourself, have I learned how to live? Have you answered that question? WARREN:I haven't answered the question, no.

Of course I haven't answered the question. How would I? I know certain things about myself when I didn't know one time, some things I don't like too. But don't ask me, which one? MOYERS: I would get the doctor. WARREN: But I do know that I have to have a certain amount of time and day for myself, and that's except for special occasions, I mean, I want to be alone with my scribbling, my thinking, my swimming or something. And I don't know why, but I guess there's a lonely boyhood. I attribute it to that anyway. MOYERS: But filled with the presence of ideas and people from the books you read? WARREN: That's right. I had a very happy boyhood actually, my summers were very happy anyway, an old rundown farm with a old grandfather who was very bookish and quoted poems all the time when he wasn't reading

about Napoleon and his marshalls, or drawing the maps of civil war battles with stick in the dust and reading military history. MOYERS: Most people don't know that about that part of the South. They still think of the violence and the terror of the South and the racism. They don't realize that in the world, even when I grew up, it was filled with writing and reading and presences beyond the known and seen. WARREN: There was a lot of reading. It's decline, or as it's a great declined a great deal too, it was declining already in my boyhood, but you could tell that it books in the house, the kind of books in the house, or the correspondence of a family.

I'd get hold of the correspondence of a family of a hundred years. A whole house being torn down several times, and I got the papers that contractor tearing it down said, I got the papers for you, and I said, I'd read them. One thing that's impressive, at least in the middle of Tennessee in Kentucky, was the will toward, well, education or bookishness in the strangest communities, but even kidnapped, a school teacher and one to another to get one, and a certain man in Allen, I think, had a big revolutionary grant of the Bowling Green in Kentucky. He was a wealthy man with a vast estate, he had built himself a fine house, but they couldn't get a school teacher. So he, a man who had commanded a regiment, you see, of regulars in the Revolution, and a man of great wealth said, well, I can do something useful, I can teach school.

So he taught school for no pay for the rest of his life, and any child that would come, could come. He was a school teacher, now that is a kind of heroism. MOYERS: Time to be alone, you say, is essential to answering that question, how to live. Do you have a television set? WARREN: No, I don't. I apologize. There's just not enough in the day, time in the day, I just say, just not enough time in the day, so much to do, and if it's television or books, like it's come down to be. MOYERS: You made your choice. WARREN: In my choice, also, I didn't want my children having passive enjoyments. MOYERS: Passive enjoyments? Explain that.

WARREN: I didn't want TV, or, I'll be honest with you, I didn't want TV around small children. I had a problem with discipline, you know, and monitoring it. And they took it, they never asked for it. They'd rush to want it in any other house, but they would say to the teacher, if he said, you could use this program for your course, "but our family's not like that. My father won't let me," and there it was. But this is eccentric, I know. MOYERS: I remember now that you wrote somewhere about the danger of our becoming consumers, not only of products, but of time not wisely used. Is that what you mean? WARREN: That's part of it, yes, and children are very vulnerable. MOYERS: Well, that provokes me to think that most people aren't poets and writers. Most people can't flee. And most people live in systems and institutions that give them very little time to themselves. And yet, as I travel the country and listen to people, they're saying, how can I create

myself? How can I signify? Do you have any thoughts? WARREN: I think part of his will to look into something that opens the inside of books, or I could say, perfectly well, I could see a perfectly well being done by TV, you see. I'm being arbitrary about that, but I'm not trying to remake the human race, I'm reporting myself as best I can to you, and what I find necessary to me. MOYERS: And pleasurable, you said. WARREN: And pleasurable. And pleasurable, yes. What about the process of writing, of creating poems and novels? Was it painful?

It's a kind of pen you can't do without. I can't say I like it, but I can't do without it. It's an old thing of scratching where your itch. Well, trying to find out what the meaning of your experience is, I've faced that way of myself now, already that is to you earlier today, I'm in trying to find out some meaning of your own experience, often writing about other people of course. This is part of you too. I find I can't do without it so far. MOYERS: Can you teach it? Can you teach a young person to write? WARREN: I don't think so, in one sense you can't. I think you can teach shortcuts and what to look for. I think you can teach certain things, which are a peripheral to the actual process. You can't create the kind of person that would be a writer, but you can help a little

bit. You can open eyes to certain things, and you can show how certain pieces of literature will work a little bit, it can be helpful. But to look for, you can modify a taste to a degree. MOYERS: In more than 30 years of teaching have you noticed any significant changes in the ability of young people whom you teach to write and express themselves? WARREN: I find an increase in illiteracy. MOYERS: Illiteracy? WARREN: Illiteracy, yes I do, right? He has an illiteracy there. Kingman Brewster is not going to be very happy with that. WARREN: Well I'm sorry. That's just true. MOYERS: Well there's all of this. Increasing illiteracy, discontinuity with the past, size, complexion, technology, even television, how does it all make you feel about the fate of democracy?

WARREN: I'm an optimist. I think God loves Americans and drunkards, keeps them out of the way of passing cars, but not of themselves. But noy of themselves, yeah. If we can, we are part of a whole great process. We are part of the whole western world, we are part of the whole drive of technology, and we are in a very tenuous, have a very tenuous hold on our goods and our chattels right now in the world, in this world. It's a very dangerous world we are living in, and we said to God I had some wisdom about it. But I think there is a streak of contempt in the American life of things that are very valuable and are available essential to our survival.

We are driving straight for a fairly straight for a purely technological society with technological controls, and our government is at the hands of the control of technologists who are not concerned about any value except mere workability, immediate workability. MOYERS: Utility. WARREN: utility. I'm not in any sense sneering at the useful things of the world, even the pleasant things of the world. I like them a lot. I met a young man a few years ago, a few years out of Princeton, such a nice young man, and nice is kind of a young American. He said, we would introduce, he said, I'm Xerox, now he is giving up his identity already. He said, I'm Xerox, he's not Mr. Jim Jones anymore.

He has no self. MOYERS: He's the organization of which he's a part. WARREN: He's the organization of which he's a part. I'm Xerox, and this is a symbol to me of a whole state of mind, of a self being ceasing to exist, it may be part of a machine. MOYERS: Is there an antidote? WARREN: I think there is, I don't know whether you guys are going to use it or not. MOYERS: What? WARREN:What? I think the proper kind of education, I mean, education has something of the humanistic about it. MOYERS: That says you matter. WARREN: It says you matter, and human beings is kind of a creature. You're talking about, you're talking about a rebel. What is it that makes a rebel, aren't you?

WARREN: I guess I am, I guess I am. Let me read you a little poem about the perfect citizen I just loved, one by Auden, that the man who is the perfect citizen, who is not a poet and not a scientist and not anything else. A good citizen, to the unknown citizen, this marble monument is erected by the state. He was found by the Bureau of Statistics to be, one against whom there was no official complaint, and all the reports on his conduct agree that in the modern sense of the old -fashion word, he was a saint. So in everything he did, he served the greater community, except for the war till the day he retired, he worked in his factory and never got fired, but satisfied as the employers, fudge motor's ink, if he wasn't a scab or odd in his views or a union report, show he paid

his views, our report on his union shows it was sound. Now social psychology at work was found, he was popular with his mates and liked to drink. The press was convinced that he bought a paper every day, that his reactions to advertisements were normal in every way. Policies taken it out of his name, prove he was fully ensured. He needs his health card, it shows he was was in a hospital, but left well cured. Both producers research and high grade living declare he was fully sensible to the advantage of the installment plan, and had everything necessary for a modern man, a phonograph, a radio, a card, a frigidaire, our researchers in the public opinion are content that he held the proper opinions for the time of the year. When there was peace he was for peace, when

there was war he went. He was married, added five children to the population, which are eugenicists say he was the right number for power of his generation. And our teacher's report, he never interfered with the education, was he free, was he happy? The question's absurd, had anything been wrong we would surely have heard. MOYERS: Now, it's chilling, it's chilling. Shades of George Orwell. What about the role of writers in our history, the writers who have shaped, questioned, contributed to these 200 years? What can you say about writers in American history? WARREN:Well, I'll say this anyway, if we start pretty early, let's start with Cooper. You find a man who creates the first great myth of America, James Fenimore Cooper.

Now he's on one hand he says you have the rape of a natural land, the destruction of a natural land, on the other hand you have the destruction of a man, a brutality that he's aware of and talks about, and also the paradox, which he has no solution for, between the values of nature and those of civilization. He has no solution for them. Let's take a case or two, look at, right, quickly, or in Deerslayer, you have two characters named Harry Harry at the go-getter, that's his name for the go-getter, the guy who's not to exploit anything, and Hutter, an ex-pirate who's driven off the seas, has hidden away

on Lake Riverglass. Now these two guys are partners in the American story, ex-pirate, and the go-getter. Now this is all, it's too pat, it sounds almost too pat, and then, this Deerslayer, a young Deerslayer, he has never killed a man. There's a camp of Indians, women, children, at some point on the lake, there's a bounty on Indian scalps, so go-getter and Harry Harry and Hutter set out to go in the camp when it's abandoned by all of the braves and kill all the women and children and sell their scalp. Now this is Cooper's view of a myth of America. And on another case, and going back to his first novel, a series The Pioneers, people

bringing canon out to kill, to kill passenger pigeons, and they've no reason to have to kill a pigeon with a cannon, they're not going to eat them, they're just going to let them rot. At the same time, they locked up in jail, the now very old Leatherstocking, because he's killed a deer out of season, to live on. That episode appears in the first one of the books, and over again you have this, he's attacking he's going at the things in the American society, he sees as an incipient, and with the same problem you're dealing with now. MOYERS: Other writers forged those myths. WARREN: Now start with Cooper, you go right ahead and you will, with William Faulkner and Cooper are agreeing right down the line, and throw us not far off that line, and then you have

another approach, which is represented by, well, I mean, most recently, most famous book about Elliot and Pound, who can say American are Philistines was another sort, and lack of spirituality, if you want to call it that. You have a whole series of the major writers who are violently, critical of America, Melvilee, westerns, violently critical, and they simply are not ordinarily, raid straight in school, they just are not read straight in school, what they say is not being told to a student. Over and over again you find it's true, and what the implications are of American literature is

extremely critical of America, and constantly rebuking America and trying to remake it, MOYERS: And yet that's so American, to be critical, to take the task, to challenge. WARREN: That's right, this is American too, you see, the fact that we produced the writers, who can take this viral attitude toward their own people and to their own society. Let me tell you something, just an anecdote -- a man, I used to know in Italy, I still know, he was a lieutenant in Italian army, when Italy got in the war in the summer of 1940, he took to the hills, with two friends, as they were, a rirle each, a few grenades and pistols, and finally joined the partisans, finally found some other discontented people to join with, and in the end was as a major, with an armoured train and an airfield of his own,

but he said that what got him off, his father fled Italy earlier, as an anti-fascist, he had his father being a musician, a kind of conductor. This young man said, stayed out because this stupid fascist, government allowed him to translate American novels, and all the novels he translated because they attacked America, he said, America novel, attacking America, you see, the Faulkner's and God knows who, and he said that to himself, a country that's strong is going to afford to attack itself and criticize itself must be very strong, so I think I'll leave the Italian army. MOYERS: We're right back to that fundamental division again. We've always seen ourselves if we read the novels as we are, and we know now that the masks have been stripped off in the last few years, and yet I still find Mr. Warren, hosts of people out there who want

to believe and want to affirm. WARREN: Well, I've been loved with America, I want to believe and want to affirm too. I've just literally, I've no other way to describe it, I just said I'm loved with American continent. MOYERS: From Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, this has been a conversation with Robert Penn Warren. I'm Bill Moyers. For a transcript, please send one dollar to Bill Moyers Journal, box 345, New York, .

Kirby's

- Series

- Bill Moyers Journal

- Episode Number

- 312

- Contributing Organization

- Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group (New York, New York)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip-621b433126f

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip-621b433126f).

- Description

- Episode Description

- Robert Penn Warren, the only writer to have received Pulitzer Prizes in both fiction and poetry, speaks with Bill Moyers about the place of his art in the modern world.

- Series Description

- BILL MOYERS JOURNAL, a weekly current affairs program that covers a diverse range of topic including economics, history, literature, religion, philosophy, science, and politics.

- Broadcast Date

- 1976-04-04

- Asset type

- Episode

- Genres

- Talk Show

- Rights

- Copyright Holder: WNET

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 01:00:24;46

- Credits

-

-

Editor: Moyers, Bill

Executive Producer: Rose, Charles

Producer: McCarthy, Betsy

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

Public Affairs Television

Identifier: cpb-aacip-eccf6f0c55c (Filename)

Format: U-matic

-

Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group

Identifier: cpb-aacip-68747e226db (Filename)

Format: LTO-5

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “Bill Moyers Journal; 312; A Conversation with Robert Penn Warren,” 1976-04-04, Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed January 11, 2026, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-621b433126f.

- MLA: “Bill Moyers Journal; 312; A Conversation with Robert Penn Warren.” 1976-04-04. Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. January 11, 2026. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-621b433126f>.

- APA: Bill Moyers Journal; 312; A Conversation with Robert Penn Warren. Boston, MA: Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-621b433126f

- Supplemental Materials