Bill Moyers Journal; 525; Judge: The Law & Frank Johnson-Part 2

- Transcript

ANNOUNCER: Funding for this program is provided by this station and other public television stations and by grants from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the Ford Foundation and the Warehauser Company. I'm Bill Moyers. Last week at this time I began a conversation with a man who's left a lasting impact on our times. His name is Frank M. Johnson Jr. but down South he's known simply as Judge. In this hour we return to Montgomery, Alabama to complete that conversation. You have only to scratch the surface of memory to recall the times when life in the South still

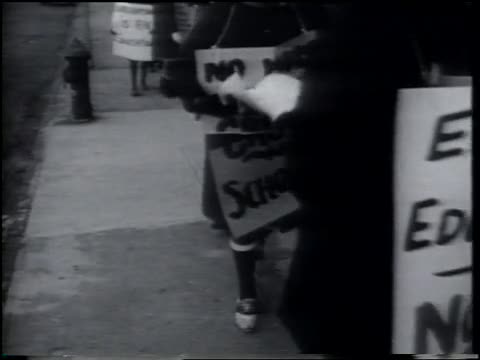

referred to as antebellum was slow and segregated. Rural Blacks lived in unspeakable conditions sold in broadcast to the world beyond. In towns and cities, Blacks were confronted with daily reminders of laws and customs that kept them separate and unequal. Most were constantly denied their constitutional rights, thus were powerless to bring about change. The poet Langston Hughes captured the frustrations of his people when he wrote in the 50s, "get out the lunch box of your dreams, bite into the sandwich of your heart and ride the Jim Crow car until it screams, then like an atom bomb, it bursts apart." It burst apart in 1955 when a 42-year-old seamstress named Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a city bus in Montgomery, Alabama to a white man. She had perhaps unwittingly detonated the civil rights crusade. From that chilly December day on, action

and reaction combined to create an inexorable pattern of petition, violence and change that lasted nearly two decades. Boycotts, marches, rallies. They all bought hatred, anger, violence and demagoguery. As Black frustration and resentment changed to protest, the worst of prejudice exploded across the South. In the midst of all the passion and turmoil, a quiet Southern judge, a Republican from the Free State of Winston County, turned the tide of white resistance with a stream of decisions that upheld the claim of Blacks to their civil rights. President Eisenhower brought him down from the hills of Northern Alabama to sit as a federal district judge in Montgomery.

It was 1955. He was just 37, the youngest federal judge in the country. Fate placed Frank Minis Johnson, Jr. in the nerve center of confrontation and change. To give you an idea of his impact on the South and the nation during his 24 years on the district bench. This is how he responded to the challenge. He declared segregated public transportation unconstitutional. He ordered the integration of public parks, interstate bus terminals, restaurants and restrooms and libraries and museums. He required that Blacks be registered to vote, creating a standard that was later written into the 1965 Voting Rights Act. He was the first judge to apply the one man-one vote principle to state legislative apportionment. He abolished the poll tax. He ordered Governor George Wallace to allow the civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery. He ordered the first comprehensive state-wide school desegregation, was the first to apply the equal protection clause of the Constitution to state

laws discriminating against women. He established the precedent that people in mental institutions have a Constitutional right to treatment, a sweeping breakthrough in mental health law. His order to eliminate jungle conditions in Alabama prisons is the landmark in prison reform. In 1969, Richard Nixon considered Frank Johnson for an appointment to the Supreme Court. Southern Republicans vehemently objected and the appointment was blocked. President Carter nominated Johnson in 1977 to head the FBI, but the judge withdrew a few months later after major surgery. Last year, after almost a quarter century as a district judge, Johnson was elevated to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. We spoke in that courtroom in Montgomery, where his momentous decisions had been made. Tonight, part two of our conversation. MOYERS: What have you learned in your own part in that process about human nature, upon which the law ultimately rests and for which it grows? I mean, someone wrote of Frank Johnson

that, quote, "his willingness to do the right thing has led him on a long odyssey into the dark side of the human spirit. The history of his cases is a history of the state as outlaw and of the savagery, which that fact has inevitably fostered." What have you learned about human nature in all these years. JOHNSON: That dramatizers it, of course, and it was probably intended to dramatize it. I think the strongest feeling that I've gained from handling all of these cases, fraught with tension and fraught with emotion, and they all were. We're talking about the civil rights cases now. We're not talking about the majority of the litigation I handled, which is just wrong of the mill federal litigation. But, is a strong feeling of respect for the American citizen, whether he's a Southerner or regardless of what section the country lives in. If you can impress him, this is a legal principle.

This legal principle is based upon our Constitutional guarantees. This is something that our Constitution requires. This is something that is the law of the land, and they may do it grudgingly, they may do it hesitatingly, but they will do it. They will do it. MOYERS: You're saying that human beings, not those change their nature, but they certainly change their perception of their nature once they're convinced that there is a higher law, a higher order to which they must correspond. JOHNSON: I believe that the majority of the people in this country will agree that the judicial decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States and the other courts that have been created by Congress, including the District Court, from the time of Marbury, and that's the first one

that established the supremacy of the Constitution of the United States and so far as other governmental bodies, including the states, were concerned. From that time until the present time, we'll all agree that these judicial decisions stand as monuments that memorialize the strength and the durability of the American government and they are proud of their judicial system as an integral and necessary part of their government. MOYERS: You really do believe in the face of law that you've seen down here? JOHNSON: I've come out of all of these with a strong feeling to that effect. MOYERS: The supremacy of the law? JOHNSON: Absolutely. And a willingness on the part of the people to accept it. MOYERS: Young people often ask me since they know I'm a Southerner. Through all that period leading up to Judge Johnson's decisions, where was the mind of the South? Where was the law? And you know

they remember Bull Connor. Bull Connor was the police commissioner in Birmingham who gave the orders to turn the fire hoses on children and to use attack dogs on children marching for school integration. Remember Bull Connor saying, "damn the law down here, we make our own law." And the question, because that was true for so long is, wasn't the law all those years the function, not of some higher reality, which you've described as being the federal perception, not of some higher reality, but of social norms and political power used for repressive ends? And that's what in the Southern history bothers so many people and remains inexplicable to them. But the question that seems to perplex us all, those of us who think about the South and its history is simply, how did this great evil segregation, racism? How did it get so deeply embedded in our part of society? JOHNSON: Well, I don't think the feeling of racism or desegregation, or whatever you want to

call it, are the strong feeling that we must maintain segregation is unique just to the South. I think that it exists in other sections of the country, but here in the South, probably it is based upon fear of unknown, fear of what will happen if the Blacks do achieve equal rights, what will happen if the Blacks secure the right to vote, to a whole public office, to sit on juries, what will happen if Black people attend our public schools with our white children? And I think probably that's the greatest thing that caused it to maybe be ingrained to start with,

and certainly to cause people to resist congressional enactments and court decisions that were designed to eliminate racism in our society. MOYERS: Fear of changing a way of life that it persisted for so long. JOHNSON: certainly, and fear of what would happen to them from an economic standpoint, what will happen when it's necessary to compete against Black people for jobs, what will happen when it's necessary to compete against them for political positions, what will happen to the social structure that we have that we prize so much when Blacks get social equality. MOYERS: George Wallace, your old nemesis, still governor, was waving his own stick around trying to get the attention

of the bench and the public and the press and saying Frank Johnson has gone way beyond what those robes entitle him to do. He's running the schools, he's running everything in this state, he's going out beyond the law to try to bring about these changes. And he was fairly successful with the ordinary voters of Alabama. Do you think that... Do you think this progress, do you think progress would have come sooner if it hadn't been for George Wallace or if he hadn't been there would there have been someone else? JOHNSON: I think there would have been someone else. They might not have been as vitriolic as George Wallace was. MOYERS: Wallace was indeed vitriolic in those early days of the 1960s, a stubborn, guileful, race-baiting politician who obstructed the path of integration at every opportunity. He harangued the federal government for its intervention. GEORGE WALLACE: And anybody who says a civil rights bill is good and any party who talks about what a good bill

it is and we're going to work for it and so forth, they're talking about a bill that was endorsed in 1928 in every aspect of it by the Communist Party who says it's the best bill ever introduced. And I ain't never heard the Communist Party recommend anything good for the United States of America, but that's the bill. MOYERS: The federal judiciary in general. WALLACE:The federal court system and I get my words from Jefferson and Jackson and Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Roosevelt who said worse things about him than I do. And if they said him I can say it too. The federal court system, a few notable exception, is a sorry, lousy, irresponsible outfit in this country. MOYERS: One judge in particular. WALLACE: Judge Franklin Johnson's order to admit six of the 12 students at the close of Tuskegee High to Shorter and six to Notasulga is an order of spite. The action of this federal judge is rash, headstrong and vindictive. This action is unstable and erratic.

MOYERS: When he was elected governor in 1962, this is how he began his turn. WALLACE: In the name of the greatest people that have ever trod this earth, I'd go the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny and I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow and segregation forever. MOYERS: You remember hearing that or hearing about? JOHNSON: I did hear it. I heard it on the radio. MOYERS: What'd you think? JOHNSON: I don't know whether I gave it too thought. I crossed these bridges when I came to them. I tried not to anticipate what would happen. I tried not to dodge from shadows. I guess I thought, well, here we go again.

Patterson had just left office and we had a good many of desegregation cases when governor Patterson was in office. I guess I said to myself, well, here we go again. MOYERS: You knew George Wallace at the University of Alabama. JOHNSON: We went through law school at the same time. MOYERS: What was he like there? JOHNSON: George Wallace was a strong follower of Franklin Roosevelt, New Dealers and New Deal concepts. He and I had many debates about socialism, governmental control of public utilities, the TVA. I was absolutely against anything, any governmental control of public utilities. It voilated my concept of what the federal government should be doing. George was probably the most liberal student in the law school at the University of Alabama. He was for a good number of years after he got out of the legislature.

He was Jim Folson, Governor Folson's campaign manager for South Alabama and Folson's one of the most liberal governors that the South had even up till now. MOYERS: Well, how do you explain what happened? What finally made George Wallace what he was? JOHNSON: George saw the handwriting. He saw that race was going to be something that he could use to his political advantage. He was shrewd and smart and capitalized on it. George Wallace was a great politician. You could never underestimate George Wallace. He would land on his feet, regardless of how far you threw him up or what position he was in when you threw him. Professional politician, the best I've ever seen. MOYERS: You think he believed all of that to hate he was spouting? JOHNSON:I don't think so. No, I never did believe that he believed it. He doesn't believe it now. He acknowledges that he doesn't believe it now. MOYERS: A lot of people believe that the first real clash between the two of you back in 1959

was just what he needed to win the governorship after he'd lost it the first time in 1958. And in fact that he came to power partly because of that incident. I'd like to review that story. It's 1959. George Wallace has been defeated in 1958 as a candidate for governor. He's still a circuit court judge and he's impounded, withheld, the voting records that the Civil Rights Commission wants in order to study discrimination in the South. And you've threatened him with contempt of court if he doesn't turn them over to the Civil Rights Commission. Is that a synopsis? JOHNSON: That's not quite the posture. The Civil Rights Commission was created by the Congress. Given authority to subpoena and examine voting rights records, not only in Alabama but throughout the country, they came to Alabama first. They subpoenaed the records from Barber County and Bullock County, two of the counties,

in then Judge Wallace's circuit. The act provided that if the subpoenas are not honored, that the Civil Rights Commission is to apply to the district judge wherein they are then functioning to enforce the subpoena. So George Wallace impounded the records from the registars in each of those counties. He told the Civil Rights Commission that I will not give them to you. If you send any FBI agents down here, I'll put them in jail. If any Civil Rights Commission employees come down here, I'll put them in jail and he made all of these firey speeches on television. I issued an order directing that he produce the records in both counties for inspection and examination by the representatives of the Civil Rights Commission. He held some news conferences to the effect that he would not do it.

I issued a show cause as order as to why he shouldn't be found guilty of contempt of court and gave him maybe 10 or 15 days. I don't recall how long I gave him to show cause in writing. In the meantime, from the time I issued the contempt order until the date he was supposed to show cause, he slipped around in the courthouse in Barber County and made most of the records available to the representatives of the Civil Rights Commission. He did it at nighttime and I made those findings and those findings are part of the court record here. MOYERS: He did it clandestinely. He was complying but he wasn't letting people know he was. And he was doing this because he didn't want to go to jail. JOHNSON: Well, he wanted to go to jail for a little while. MOYERS: He was afraid that you would put him up for a long time. JOHNSON: l told him if he didn't produce the records like I'd ordered him to. I'd pop him in jail for as long as I could. MOYERS: Let me examine that because the story is that while all this is going on, he sought a meeting with you that he wanted to come to

your house to work out something and that he came to the house. JOHNSON: That's true. MOYERS: And he knocked on the door. Now the story is that when the door opened, there he was, holding his coat over his head. JOHNSON:That's true. It was true. It was true? He didn't want the neighbors to know that he was calling. JOHNSON. He didn't want anyone to know. What did he say? That's the way George operated. What did he say? Yeah. He said, George, my ass is in a crack. I need some help. That's to quote him verbatim. My wife was in the bedroom. She heard him say, George, come on in. I've made some coffee. He had had a mutual friend call me and tell me he was driving over a hundred miles to see me. And I had some coffee for him. And we had a cup of coffee. And that's when he asked me if I'd send him the jail just a little while. It would help him politically. And I told him no. If he didn't comply with my order, I'd send him the jail for as long as I could. MOYERS: George thought. George Wallace thought you could send him up for three years.

But under the law, how much time could you have given him? JOHNSON: Well, it depended on whether I proceeded with contempt under the Civil Rights Act. And I think it had a maximum of 30 or 40 or 50 days. Or whether I proceeded under the general contempt statute. I could have sent him up for six months. That's how he would have had the best of both worlds. He wanted to be able to say he defied your court. But at the same time, he wanted to give them to the Civil Rights Commission. JOHNSON:Sure. And he did. And when I made the findings that he had complied, even though surripitiously and deviously, and discharged him from being in contempt, because he hadn't complied, that's what gave rise to his cry that he made famous, said. "Anybody that says I didn't defy the federal court, anybody that says I didn't back ' em down, is an integrating and scallywagging, carpet-bagging liar. MOYERS: Namely, Frank Johnson. Well, sure. But everyone that studied the record and everyone that knew the situation, knew that George Wallace had slipped the records to them.

MOYERS: And yet, was able to say he had defied the federal government. JOHNSON: He sold it to a large segment of the people in Alabama. He absolutely duped and hoodwink. MOYERS: He needed you, didn't he? He needed you. Of course. He needed as a scapegoat. He needed anyone. Just like any demagogue needs. JOHNSON: Sure. I was just in a place that he could use. MOYERS: And yet you must have despised everything George Wallace was up to, to defying the law of arousing passion. JOHNSON: Of course. Absolutely. Absolutely. I despised the fact that he was using the people in the state of Alabama for his own political games, that he was lying to them, that he was misleading them, that he was promising and holding out hope that he knew he couldn't give them. Did that not make him a county case? Let people to believe that they never would have to desegregate their schools. George couldn't believe that. MOYERS: The irony strikes me that George Wallace had the voters. He had the notoriety. He had the ambition.

And he had the guile. But in the end, it was an unelected, federal judge who altered forever the face of the South. JOHNSON: Well, I think people eventually came to the realization that the decisions that Judge Johnson been making are not all bad. The decisions that Judge Johnson has been making have not destroyed us like we were told they were going to do. They haven't destroyed our institutions like we understood. Our daughters haven't been raped because of these desegregation orders. I think they realized they had been duped just to put it bluntly. And most of them know now that they had been. MOYERS: You know, Judge, it's rather remarkable when one thinks about it, and bear with me on this because it's a long litany. But either a singly or as a member of a three-judge panel,

you desegregated Alabama schools, you desegregated the buses, the bus terminals, the parks, the museums, the mental institutions, the jails and the prisons, the airports and the libraries. You ordered the legislature to reapportion itself. And when it refused, you drew up the first court-ordered legislative reapportionment in history. JOHNSON: I gave them 10 years to do it before I did that. You changed the state's electoral system and voter registration procedures. You abolished the poll tax before the Congress had ever acted. You were the first judge to put in the South, the first judge to put women on your juries. You changed the system of taxation in Alabama. You took over the administration of the prisons and the mental institutions. And when I read that litany, I think of something Lyndon Johnson said to some of his friends that the night after the march from Selma to Montgomery was over. He said, you know, I wouldn't have to be president if my name were Frank Johnson instead of Lyndon Johnson. MOYERS: Did you ever think about having that much power, more power to accomplish in the South

than the governor of Alabama and even the president of the United States? JOHNSON: Federal judges are given lots of power. They were given that power deliberately. You have federal judges that are appointed during good behavior for life, so to speak. That insulates them from social pressures, insulates them from political pressures, insulates them from economic pressures. And so federal judges are given that power and given that insulation from any outside pressures so that they may act impartially and they may act courageously. And when they accept an appointment as federal judge, they impliedly agree with their government that if I'm appointed federal judge, if I'm given this lifetime appointment tenure in office, if I'm given these insulations from outside pressures, then I will act courageously and I will decide these cases

impartially. More specifically in response to your question. It never occurred to me that all of this litigation was coming. I took these cases case by case. All of them didn't come at one time. You've talked about civil rights litigation over a period of 24 years. MOYERS: It's quite a body of work for one man. JOHNSON: Well, it was interesting. And in retrospect, it was worth it. MOYERS: It raises the question, gets us right to the heart of one of the most profound controversies in the land today and in the history of the judiciary. And that is the heart, the question of judicial activism, judicial interventionism, judges beginning to get involved in so many aspects of our lives that they have become,

according to some critics, the dominant force in our lives. It's what, you know, the most harsh critics have called an imperial judicial oligarchy, a ruling class accountable to no one. And I'm just wondering if you don't think there isn't some merit to George Wallace's notion that a non-elected federal judge has no business running a state's prisons, tax systems, mental institutions, and schools. JOHNSON: Well, I'll answer the last part of that question first. I do think a federal judge has no business running a state's institutions such as prisons and schools and mental institutions. But the state has defaulted in those areas or the federal judge wouldn't find it necessary to step in. But I haven't stepped into the point that I've run and the popular sense of the word any of the institutions. I've imposed minimum standards so that it was necessary from the comply with in order to eliminate the Constitutional problems that necessitated

federal court intervention to start with. Federal courts have not engaged in what I consider unwarranted judicial activism in all of those decisions. And the decisions in the main, with a very few exceptions, they're discharging the Constitutional duty that's imposed upon them. DeToqueville put it in a very good way when the judge always comes with his precedence. He wrote this, the French historian who came over here and studied our Constitutional system. He said the American judge is brought into the political arena independent of his own will. He only judges the law because he's obliged to judge a case. The political question which he's called upon for his all is connected with the interests of the parties and he cannot refuse to decide it without abdicating the duties of his post. And then he said this, "the peace and prosperity

and the very existence of the union," talking about our union, "are invested in the hands of the judges without their active cooperation the Constitution would be a dead letter. The executive appeals to the court for assistance against the encroachments of the legislature. The legislature demands their protection from the designs of the executive. They defend the union from the disobedience of the states. They defend the states from the exaggerated claims of the union. The public interest against the interest of the private citizens" and it should be added that the courts, the federal courts defend the interest to private citizens against the government. MOYERS: I can see that historical that that history judge. It's been an argument ever since the first date as you said. But the reason you become controversial and judges like you, you're not alone in this, has been because you've moved into what the scholars call structural reform whereby a

judge tries to reorganize a bureaucracy in the name of Constitutional values which he believes have been threatened. In particular, I'm thinking of Newman versus Alabama in which you actually took over responsibility for the state prisons and Wyatt versus Stickney in which you took over the mental hospitals. And the question is, had the Constitution been so interpreted that way in the past so that the federal judge actually assumes the administrative power over a state agency? JOHNSON: We've moved from litigation that was involved with property rights and capitalism to litigation that's involved with human rights and civil rights. The people in this country have become conscious of the many, many additional governmental controls that are imposed upon them. The regulatory society. In the environment. In every aspect of life and they seek refuge in

the federal courts, I don't mean governmental controls imposed just by the federal government. I mean by the state government. Litigation is no longer a bipolar thing between two parties. It's a class action that's brought to vindicate the rights of classes. Our federal procedures have been changed to recognize and even in proper circumstances encourage class action litigation. The class action litigation, such as you mentioned, for the prisoners, challenging the conditions in the Alabama prison system. The Newman case was one that alleged the deprivation of medical care and treatment. Pugh against James was one that alleged Eighth Amendment violations because of the general conditions in the Alabama prison system. Wyatt against Stickney was one that alleged on behalf of the class of over 5,000 people

deprived of their liberty through civil proceedings in the state of Alabama and incarcerated in the state mental institution for treatment purposes that they were not receiving treatment. And so they raised Constitutional issues. They presented them to the federal court. And there's no way for a federal judge to discharge his oath of office if he tells those people I'm going to award you some damages for the things that they've done to you in the past. That's not much solace to a prisoner that doesn't have a decent or safe environment. To award mental patient damages for what they've done to him by depriving him of treatment in the past won't get him in the thing in the future. So the litigation has not stayed the type that asked for redress for passed wrong. MOYERS: Which is the traditional way.

That's right. Two parties come together and you say you were wrong, pay this person. JOHNSON: The litigation now seeks prospective relief. It seeks the elimination of conditions that exist. And most of these cases they aren't particularly interested in damages. You rarely ever have a claim for damages where in a case like the prison suit or the mental health suit, and so the judge is confronted with this new type of litigation and there's no way to and he shouldn't attempt to dodge it. MOYERS: In both cases you said conditions in the mental institutions and conditions in the hospitals were intolerable. When you looked into them what did you find? JOHNSON: Well I found that in the Bryce facility located in the Tuscaloosa area which is the largest for mental institutions in the state of Alabama. Over 5,000 people had been committed there for treatment for their mental illness. Had been committed by the courts of the state of Alabama. They'd

been deprived of their liberty for the purpose of giving them treatment. And the evidence showed that they weren't getting any treatment at all. They were being warehoused. And so the Constitutional issue was presented. Were they entitled to treatment? And I held as a basic principle before we ever got into the type of relief that they may have been entitled to. I held that people that are committed through state civil proceedings and deprived of their liberty under the altruistic theory of giving them treatment for mental illness and then warehousing them and not giving them any treatment at all, strikes at the very core of a deprivation of due process. And that they were entitled, if they are deprived of their liberty for treatment purposes, then they're entitled to some treatment that is medically and minimally acceptable. And not entitled to the best treatment and I emphasize the word minimally and I used it in that. MOYERS: But what criteria did you use? I remember

Judge David Bazelon of the Court of Justice in Washington who said that his criteria for intervention goes far beyond just minimum standards of justice and fairness. And he said his test was a gut reaction to a situation which he said "does it make you sick." Now when you went into those prisons and into those mental institutions did it make you sick? I've never been in prison. I've never been in a mental institution. I didn't find it necessary to go there. Well how could you not want to get a gut reaction? I did not want to base my decision on any emotional feeling I might get from visiting those places. I wanted to base it on the evidence that was presented in the court where in an adversary proceeding where both parties had an opportunity to present evidence and be heard. And the evidence in this case and the state mental case was overwhelming that they weren't getting any treatment they were being warehouseed. You had 1,600 people out of 500 that wouldn't benefit from any treatment at all that were taking space in this mental hospital.

They were geriatrics. The only thing that they were suffering with was the ravages of old age. They should have been in a nursing home. You had 1,000 of the 5,000 that weren't mentally ill at all. They were retardates that should have been in an institution for retarded people and subjected to some program design to habilitate them. MOYERS: And you didn't need to go there to discover JOHNSON: Absolutely not. I needed not to go there. A judge shouldn't go visiting a place that he has under scrutiny in a lawsuit and base his decision in whole or in part on what he's observed unless he's going to submit himself to cross-examination. He should do it on the basis of evidence that's presented during the adversary proceeding. And so I've been criticized for not going to Bryce hospital. I've been criticized for not visiting the penitentiaries. But that's not the approach in my judgment. MOYERS: How did you determine what appropriate relief consisted of? I mean,

the court order you issued from that bench was incredibly comprehensive. It covered everything from the amount of space allotted to each patient, the number of toilets, the frequency that each patient had to be bathed, down to requiring that toothbrushes be provided and toenails cut. JOHNSON: Federal judges are trained in the law. They're not penologists. We're not psychiatrists. We're not educators that can run the schools, yetnwe've entered the school's orders setting forth in detail what your faculty ratio should be and what your pupil ratio should be, what kind of a facility you should have. If you had an ideal situation, you would have these cases decided by the penitentiary, a penologist, and the mental institutions, psychologists, and psychiatrists, and the school cases by educators. But federal judges have the job of doing it. But we have

tremendous number of aides. We don't fly blind in these, you have experts. For instance, in the Wyatt - Stickney case, I had experts, that's the mental health case, come to this court and testify from that witness stand from all over the United States, ranging from the Karl Menninger from Topeka, Kansas to psychiatrists and psychologists and mental institution experts from California to Maine. And I based my decision and I based these minimal standards on their testimony. MOYERS: You said in your in your ruling, quote, "a state is not at liberty to afford its citizens only those Constitutional rights which fit comfortably within its budget." And the question arises, if a legislature refuses to appropriate money, what power does a court have to make it? JOHNSON: Well, to answer your question as

it's asked, a federal judge cannot make the legislature appropriate money. There are many alternative means, though, by which a federal judge can enforce his order. He has contempt power by those that are charged with operating the institution. He can close the institutions. He can say to the state of Alabama, well, it's fine that you're operating a mental institution or it's fine that you're operating a prison, but you cannot operate it and continue to violate the Constitutional rights of those that you've incarcerated there. You either have to comply or close your facility. That's a drastic measure, but some courts have done it to a certain extent. You have the authority to appoint receivers to take over and run the institutions and attempt to do it in a more efficient manner and more effective manner and eliminate these egregious wrongs that exist that form the basis for these decisions. These orders were not entered in on an attempt on my part

and they're not entered as far as I know as an attempt on the part of any federal judge to make hotels out of these prisons. MOYERS: That's what George Wallace said. Oh, yeah. So what you say to George Wallace and he said, you want a hotel? JOHNSON: Well, I said putting quadriplegic in the bed and not changing his bandages for 30 days and letting maggots get in his sores is not running a hotel. Putting a man that cannot control his bowels on a board instead of letting him lay in the bed and making him sit on the board until he falls off two days before he dies is not running a hotel. Stopping things like that is not creating hotel conditions is what I said. MOYERS: He said you wanted utopia. You and all the other men in robes who kept trying to dictate to the state really were after utopia. JOHNSON: The federal courts are not omnipotent and not tyrannical and those that criticize the

courts on that theory are just absolutely wrong and they don't understand the history and they don't understand the Constitutional restrictions that federal courts operate on. We can't go out and just reach out and get cases. We can't and we're restricted from issuing advisory opinions. The only time we can rule is when there's a genuine case or a controversy between litigants that have standing to bring it. We do not make the facts that form the basis for the litigation. MOYERS: Which is higher, the conscience of the people, the conscience of the court. JOHNSON: Well, they shouldn't be any different. They shouldn't be any different. They should be the same. Court opinions can on a short run be enforced against the will of the people. On a long run there's no weight to enforce on them against the will of the people if they violate the conscience of the people that

won't stand. For court decisions to be effective they must be accepted with the people. That's the reason at the beginning of this discussion that we've had I attempted emphasize that people have accepted Brown Against Board of Education. People have accepted cruel and inhuman treatment cases such as a Pew against James and deprivation of medical attention such as the Newman case and treatment for them and and habillitation for the menally ill and retarded. They've accepted that and they're proud of it. They've accepted the implementation of Brown and the people I submit to you in this section of the country, and not just talking about Alabama, are proud of the fact that we have with a minimum amount of disruption implemented a case that cut across the social fabric to the extent that that case did. JOHNSON: Well you've said "I'm not a crusader". I've read other statements you've made when you said I don't make the law, I don't create the facts,

I interpret the law. But pragmatically when a judge interprets an old law in a new way he's actually making new law isn't he? JOHNSON: I wouldn't think so. The Constitution of the United States and we're talking generally and we have been about cases involving Constitutional questions. The Constitution of the United States has right at 5,000 words in it. It's a bare outline that we refer to as our charter of government. It takes interpretation on the part of judges and on the part of courts to make the Constitution a document that preserves rights now. And it may have been construed most restrictively and literally at that time and covered most if not

all the questions presented. But there's no way to construe the Constitution of the United States literally at this time and make it a document that has any viability. And if that's called you judicial activistism then I submit that it's something that's necessary in our form of government unless we want to spend all of our time amending and enlarging and changing the Constitution. MOYERS: Let's see if we can if I can understand it more graphically by looking at a particular case of very important decision you made back in the early 60s when Martin Luther King and his followers were preparing to march from Selma to Montgomery, now a celebrated historical episode in the life of of our country. I remember sitting in the White House with the president his his advisors waiting for your decision. The word out of Montgomery that was that you were taking your time that you

weren't sure you were going to to to grant the marchers the right to to to march. And then there was that incident at the bridge when the marchers were beaten by by some of the authorities he JOHNSON: State troopers. MOYERS: State troopers. In the winter of 1965 Martin Luther King chose Selma Alabama to be the target of a massive voter registration drive to expose and eliminate the barriers Blacks faced in the expression of their 15th Amendment right to vote. To dramatize their battle to find a national audience King called for a massive march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama's capital. Governor Wallace issued an order forbidding the march. They went anyway. What happened next at the Pettus Bridge needs no explanation. And then you came down with your judgment and you allowed the marchers to proceed from Selma

to Montgomery and by your own admission that decision quote "reached to the outer limits of what is Constitutionally possible." And you said in your ruling and I like to quote it quote "it seems basic to our Constitutional principles at the extent of the right to assemble, demonstrate and march peaceably along the highways and streets in an orderly manner," and here's the here's the phrase "should be commensurate with the enormity of the wrongs being protested and petitioned against." Now your critics ask if Frank Johnson had not personally thought that the wrongs were enormous would not the demonstrators have lost their First Amendment rights. JOHNSON: No, not at all. I did not issue that opinion. I did not write those words before having a hearing and taking evidence. The purpose of the proposed demonstration, and it was a demonstration, was to attempt to secure a redress for grievances that had existed over many many years in Alabama.

That is the deprivation of the right to register and vote in so far as Blacks were concerned. The evidence that case showed that in some counties in Alabama there were 113 percent of the eligible white people registered to vote. There were two percent or three percent or four or five or up to six percent of the eligible Black people registered to vote. It shows that in Macon County, for instance, they were over a hundred percent of the white people registered to vote and entitled to vote. But in a county where you have a large percentage of Black people with college degrees, some with doctors degrees, some with several college degrees, all failing the examination that the registrars were giving them as a test as a precondition to register them to

vote. You had a situation in Selma where when they lined up to vote some of them had been subjected to electric cattle prods. Some of them in the state that I was familiar with from having handled voting cases in many counties in this section of the state had been required to write the Article II to the Constitution of the United States. Whites were not given any similar test. So you had a wholesale deprivation by the authorities representing the state of Alabama in this section of an entire race of people that wanted to secure a right that was basic to their citizenship. MOYERS: Why did you wait several days before granting the permission to give the rights because there was doubt in Washington after a while 24-36 hours that you might decide in their favor.

Some people even say I don't believe he's going to grant the right to the march. No, no judge doesn't go to court with one opinion written out in this pocket if he decides that way and one written out in this pocket if he decides that way. He has to hear his evidence, he has to evaluate it, he has to write it. Decisions of this import should not be rendered orally. They should be in writing and they should be well documented as far as legal authority concerned. And it takes a day or two for even the speediest judges to act. MOYERS: And you decided that this record of discrimination against Blacks in voting, the removal of which was the object of the march, was so great, so grave that they were justified in marching from Selma to the government. JOHNSON: Absolutely, if the deprivation had been restricted to maybe 50 or a hundred people, not over an extended period of time, then this theory of proportionality,

and that's what it was, the right to demonstrate and redress, or petition for redress for your grievances should be in proportion to the wrongs that you're petitioning against, that you're trying to dramatize. If it had just been deprivation of a hundred people to vote, it wouldn't have justified a march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. If some Black person had been fired by the state as an employee, solely because of their color, that wouldn't have justified any demonstration of this magnitude. But this, as I said a while ago, was a deprivation that concerned the whole Black race in the state of Alabama and it had been long and it was a grievous form of discrimination. MOYERS: There's an interesting case you decided just two years ago. The first time it had ever been decided that a Black institution was found to have

discriminated against whites. That was made right here in this courtroom. It was against the Alabama State University, which is an-all Black school. JOHNSON: Well, not all Black, predominately black. It was established in an all-Black school and you decided that it had been discriminated against to some extent now. MOYERS: And you decided that it had been discriminating against whites. Tell me about that case. JOHNSON: Well, the case was presented through the pleadings. A group of white faculty members hired a lawyer and filed a lawsuit as a class claiming that the Black administration at the Alabama State University had discriminated against them on the basis of their race. Some people refer to it as a reverse discrimination case. There's no such thing as a reverse discrimination. It's just plain old discrimination whether the whites do it to the Blacks or the Blacks do it to the whites. And they the evidence reflected that there had been discrimination against

the white faculty members on a wholesale scale and I'm so found and enjoying them from doing it in the past and in the future. I required that they make some monetary awards to compensate for or partially compensate for what had been taken away from them. The same kind of case that I've entered a dozen times against white schools, Blacks got incensed just like the whites get incensed when a ruling comes that they don't like. Sure, I got letters, telephone calls, I got publications in the Black newspapers about that judicial activist sitting on the bench down there in the Alabama, about that lawyer that engages in the exercise of arbitrary. I mean that judge that engages in the exercise of arbitrary power and same old song, same old dance. MOYERS: Did it affect you?

JOHNSON: Of course not. MOYERS: So in the last analysis, old question old debate, do we have a government of laws or a government of men? JOHNSON: Well, we have a government of laws. Judges decide cases according to the law. True, as we said a while ago, judges interpret the laws. They interpret the laws through their own eyes. They pour what's necessary into an empty vessel as Judge Hans says. But they still are not imposing their own sense of morality on the people or the litigants when they decide this case. They're imposing what they determine to be the morality required by the Constitution of the United States and that's the role of a judge. MOYERS: There's no job like it is there. Could you have done anything else? Would you like to have done anything else? JOHNSON: Oh, if I could go back and choose,

I'd go the same route, the same route. I've enjoyed it and most fulfilling. JOHNSON: Thank you very much, Judge Frank Johnson. Thank you. For a transcript of this program, send two dollars to Bill Moyer's Journal,

Box 900, New York, New York, 101, 01. Please include the program title with your request. Funding for this program has been provided by this station and other public television stations and by grants from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the Ford Foundation and the Warehouse Air Company.

- Series

- Bill Moyers Journal

- Episode Number

- 525

- Contributing Organization

- Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group (New York, New York)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip-375941fdc86

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip-375941fdc86).

- Description

- Episode Description

- Bill Moyers talks with Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr. about his landmark civil rights decisions, his years on the bench and present-day Constitutional issues. Part 2 of 2.

- Episode Description

- Award(s) won: EMMY Nomination-Programs and Program Segments

- Series Description

- BILL MOYERS JOURNAL, a weekly current affairs program that covers a diverse range of topic including economics, history, literature, religion, philosophy, science, and politics.

- Broadcast Date

- 1980-07-31

- Asset type

- Episode

- Genres

- Talk Show

- Rights

- Copyright Holder: WNET

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:59:41;01

- Credits

-

-

Editor: Moyers, Bill

Executive Producer: Konner, Joan

Producer: Bean, Randy

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group

Identifier: cpb-aacip-2b42b2f4977 (Filename)

Format: LTO-5

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “Bill Moyers Journal; 525; Judge: The Law & Frank Johnson-Part 2,” 1980-07-31, Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed January 8, 2026, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-375941fdc86.

- MLA: “Bill Moyers Journal; 525; Judge: The Law & Frank Johnson-Part 2.” 1980-07-31. Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. January 8, 2026. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-375941fdc86>.

- APA: Bill Moyers Journal; 525; Judge: The Law & Frank Johnson-Part 2. Boston, MA: Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-375941fdc86

- Supplemental Materials