NOW with Bill Moyers; 306; Elizabeth Warren on two-income families; Campaign ads; Job loss in Michigan

- Transcript

Transcript, February, 2004

ANNOUNCER: Tonight on NOW WITH BILL MOYERS: Why are so many middle class families going broke?

WARREN: The middle class has been pushed right to the edge. They are on a cliff. And increasing numbers are falling off every single day.

ANNOUNCER: Elizabeth Warren on the two-income trap. A Bill Moyers interview.

And, on the eve of the next round of caucuses, David Brancaccio reports from the front lines of the jobless recovery.

MIKE HUCKLEBERRY: People don't understand. They're angry and they're frustrated and they don't understand why our government would allow this to happen.

ANNOUNCER: And Congress has become the millionaire's club.

STRUBBLE: If you can't raise enough money to play in the game and get on television with a lot of ratings point, you have a very low chance of winning.

ANNOUNCER: TV ads and the commercialization of democracy.

And grassroots politics where the party is just getting started.

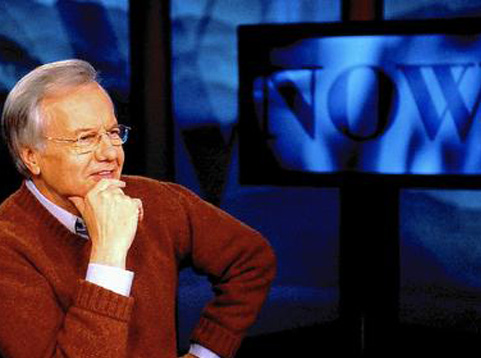

BRANCACCIO: Welcome to NOW.

For Americans at the top, the news seems all good. The economy in the last quarter expanded by 4 percent. The stock market is up 40 percent over the past 15 months. Big profits are back on Wall Street, and this week, the WALL STREET JOURNAL is chronicling how high flyers are spending their lavish year-end bonuses on things like Lamborghinis and weddings at the palace of Versailles.

Now, step down the ladder a few rungs, and life looks quite a bit different.

MOYERS: It was summed up for me in a five-word sentence in the NEW YORK TIMES, "Family finances are being stretched." The story goes on to chronicle a prolonged borrowing spree in America: families piling on debt to buy homes, charging new computers to their credit cards and driving new cars bought on dealer credit, and renovating their houses with home equity loans. The result is a doubling of household debt since 1990.

Political candidates take note — we're not making this up — there's an invisible crisis building out there. By the end of this decade, says a new book, nearly one of every seven families in America with children may have declared itself flat broke. This year alone, more people will end up bankrupt than will suffer a heart attack. And more people will file for bankruptcy than will graduate from college.

For desperate Americans, it's scary. Look what happened in the Washington, DC area this week when WKYS, a hip-hop/R&B radio station, ran a contest offering to pay the winners' overdue bills.

DJ: I'm just payin' bills! Throwing them all over the place.

MOYERS: More than 20-thousand people sent in their bills: mortgage, gas, tuition, child care bills. The station had to replace its fax machine three times to cope with the flood of paper.

DJ JEANNIE JONES: This contest proves that folks are still in a lot of pain. They're scraping up everything they have to survive day by day.

MOYERS: Even though unemployment figures improved slightly last month, 8.3 million Americans are still on the rolls, and many families today are just one lay-off away from economic collapse. That is not our opinion.

This is the book I mentioned, THE TWO INCOME-TRAP: WHY MIDDLE-CLASS MOTHERS AND FATHERS ARE GOING BROKE. Elizabeth Warren is one of the co-authors. She's a leading expert on bankruptcy, debt, and the middle class. Cited five years ago as one of the fifty most influential women lawyers in America, she teaches at Harvard Law School. Elizabeth Warren wrote this book with her daughter, Amelia Warren Tyagi.

Welcome to NOW.

You say in here that every 15 seconds some American is filing for bankruptcy?

WARREN: That's exactly right. That's 365 days a year, 24 hours a day. In fact, this year, more children will live through their parent's bankruptcy than will live through their parents' divorce.

MOYERS: Well, what are we to make of that?

WARREN: I think what we're to make of it is the middle class has been pushed right to the edge. They are on a cliff. And increasing numbers are falling off every single day. Families live in a much more dangerous economic world than they did a generation ago.

They tried to deal with it by sending both mom and dad to work. You know, a generation ago, early 1970s, the median earning family had one person at work.

And today, just 30 years later, the median earning family has two people at work, and now here comes the zinger. Even though they're making 75 percent more money in inflation-adjusted dollars, because now they've got those two incomes, by the time they pay the mortgage payment, health insurance, a second car, because they're further out in the suburbs and mom needs to get to work, and pay for their pre-school and daycare, they actually have less money to spend than their one income parents had a generation ago.

And what we found was that well over 90 percent of the families who file for bankruptcy, when you look at the enduring criteria, are middle class families.

They're moms and dads who worked hard, played by the rules. They went to college. They bought a house. They had kids. And then they ended up in financial collapse.

Also, I need to make clear here bankruptcy's just a little piece of that iceberg. Not only will 1.6 million families file for bankruptcy this year, but in addition to that, we've got 9 million families who are in credit counseling already.

MOYERS: Which means?

WARREN: Those are the folks who have gone to see someone hoping they can get bailed out without having to go into bankruptcy, but it tells you they're in serious financial distress. And look at the other indications. Home mortgage foreclosures are up more than three-fold over the last generation. Credit card default rates are at record levels. Car foreclosures are at record levels.

In fact, let me give the closer on this.

One of the big national surveys trying to find out the things families are concerned about found that more than 70 percent of families interviewed said worry over money is now infecting their family lives.

MOYERS: Infecting it?

WARREN: Infecting their family.

MOYERS: In a toxic way?

WARREN: Of course in a toxic way. What does it mean to be a parent who's trying to decide "If I buy Girl Scout uniforms and a band instrument this month, will I still be able to pay the mortgage?"

Parents are waking up at night worrying about whether they can make the utility payment, wondering how long they can run out on the car payment before someone comes and pulls the car out of the driveway and takes it off and sells it.

MOYERS: The popular notion is that families are spending too much, buying things they don't need. What did you find out?

WARREN: I thought I was gonna write a book about overspending. I thought this is it. I got it. This book is gonna be about too many trips to the mall, too many Game Boys, too many…

MOYERS: That's been done. AFFLUENZA. Remember that book? That…

WARREN: I do remember that book. Exactly. I thought, "This is the book I'm gonna write." I mean, I can't get a parking place at the mall. Right? That had to be the problem. So what we did is we got old, unpublished, government data. It turns out the government's been collecting this for a long time about how families actually spend their money.

And we look at mom, dad and two kids 30 years ago, and mom, dad and two kids today. And remember, today, they've got two incomes. You know what we discovered about… Let's start with clothing. How much more are they spending today on clothing than they spent a generation ago? All those designer clothes. All those $200 sneakers. You want to know the answer?

Twenty-two percent less than they spent a generation ago. Less. Okay, food. They're eating out today, right?

MOYERS: Yeah.

WARREN: Mom's not there in the household. She's not cooking those meals at home. So when you add up all that they're spending on food, all the designer water, all the fancy things they're buying, all the pre-prepared food, all the eating out, how much more is today's mom, dad and two kids spending on food than they spent a generation ago? Answer: 21 percent less.

MOYERS: Less.

WARREN: Appliances. Hey, they have microwaves, and nobody had a microwave a generation ago. They have espresso machines today, right? Fancy popcorn poppers. The answer is today's family is spending 44 percent less on appliances than they spent a generation ago.

MOYERS: So, where's the money going?

WARREN: It's going to the mortgage. It's going to the health insurance.

Daycare, childcare, nursery school. Something to take care of the little ones. And a second car, so that mom can get to work. Those four expenses have more than eaten up all of mom's income that she's brought into the game, and eroded what dad earned.

MOYERS: I want people to read the book, because they'll get the full answer to this. But give me a quick summary of why this has happened.

WARREN: The causes are disparate. They're scattered everywhere. Part of the cause is in health insurance, and what it's cost to be able to ensure a family against the extraordinary medical cost that any family faces, if something goes wrong.

Another part of the cause is the failure in our public school system. You know the reason that housing prices are shooting up is not because families want spa bathrooms and granite countertops, right?

MOYERS: McMansion.

WARREN: That's right. This is another version of the over-consumption myth. Hey, if the top ten percent buying spa bathrooms and granite countertops, absolutely. The median earnings family's house has gone from 5.8 rooms to 6.3 rooms. Okay, they've picked up half a room.

But they are paying extraordinarily more money. As I said in inflation-adjusted dollars they're paying more than 70 percent more than their parents paid for a house a generation ago. But here's the difference.

A generation ago, mom and dad bought a house they could afford. That's how they shopped, and they counted on being able to send the kids to the school down the block. And it mostly worked for the middle class.

What's happened today is that young parents buy houses with just three thoughts in mind, schools, schools and schools.

You know, and I want to be clear. It's not just that they're all trying to buy into the fanciest school district, whatever that is in the neighborhoods. Where can I buy a house that will give my children a chance to move forward?

MOYERS: It's distressing to hear you, because I think you are describing reality. I have read the book, and I've looked at the data that you back it up with. But what's happening as you describe this reality is that wages are not rising anywhere near the needs that you are describing and defining.

WARREN: I think that's exactly right. What's happening today is that men's wages are flat. Women's wages are rising, because they're approaching men's, although that seems to be flattening out a lot.

But costs, costs for what it takes to be middle class, those costs have shot way out of control.

Families have controlled what they can. They've cut back on clothing. They've cut back on food. They've cut back on appliances. They've cut back on furniture. They've cut back on floor covering. All of those costs have been pushed down in the family, and that's why I say the families now are right against the wall. They don't have any flex in these budgets. If something goes wrong, they're in high fixed expense territory. And if they have to give something up, they're giving up the things that make them middle class.

MOYERS: You haven't even talked about the single-parent family.

WARREN: Oh, we have a chapter in this book called "Trying To Make It On One Income In A Two Income World." When we talk about the two-income trap, we picked the two-income family to focus on, on the notion that that's the one all of us believed is the successful economic unit. The family that's going to succeed.

If I'd written a book about how one income families are in trouble, you'd have said, "Well, gosh, Elizabeth, why didn't you look at the ones who are really out there and making it?" But the consequence of a world that has shifted from one income to two income as the norm, two incomes just to make the basic expenses of the mortgage, the health insurance means one income families have been left in the dust.

Today's one income family, whether it's headed by a man with a wife who tries to stay at home or whether it's headed by a woman who's trying to make it after a divorce are at the ragged edge of the middle class.

MOYERS: Have the political decisions in Washington contributed to the trap you're talking about, to the dilemma you're discussing?

WARREN: Absolutely. I mean let's talk the long view. Following the Great Depression and the heart of the Great Depression, we began to understand that we'd better change our policies to support that middle class, because without a middle class, we don't have an economy and we don't have a safe democracy.

Following World War II, we got another big focus on the middle class. Remember the G.I. Bill?

MOYERS: Oh sure.

WARREN: It was all about getting a free education, so that you were ready to go into that work force. It was also about how can we help people buy homes, affordable homes, right? The whole notion of FHA grew up then, and the V.A. loans, the idea that we're gonna aim our government policies towards supporting the middle class.

There was a fundamental change in the early 1980s, and the fundamental change was that we switched over to letting all of those little boats go it alone. And the focus moves to the two ends of the spectrum.

There were the advocates who fought on behalf of those who lived in abject poverty. God bless them for doing that. And there were the advocates who fought on behalf of "let's unleash the power of corporations. Let's make it possible for the rich to be incentivized to get out there and earn and work and do what they can." And that's where government moved. That's where policies moved. That's where interest groups moved. That's where focus moved.

And the middle class, look, we all thought the middle class was strong enough to take care of itself. Over time what happened was an eroding educational system with no support for changing demands and the kind of education that parents need to provide for their children, pre-school, college. We began to leave all that to be privatized, to be born by the individual family. And the middle class is starting to get hollowed out economically.

MOYERS: What did it mean when 25 years ago, the lending industry, the banking industry was deregulated? What did that mean for these people?

WARREN: The deregulation of the consumer credit industry gave us lots of good things. Lots of credit available out there. Lots of people who can go out and borrow at low interest rates, but it also gave birth to a monster. And that monster is now eating middle class American families. That monster…

MOYERS: And that monster?

WARREN: It's sub-prime credit. It's predatory lenders. It's learning that when the wholesale cost of money, that is what the banks can borrow the money for is down around two percent and they can find ways to lend it out at 18 percent, 22 percent, 26 percent, 34 percent that there are staggering profits to be made here.

And it's middle class families who are paying that money, and more to the point, it's middle class families who get tangled in that debt when they lose a job, when somebody gets sick and they don't have health insurance, when they divorce.

So, the consequence is that credit card companies which this year will collect $78 billion, that's billion dollars, in interest charges are in effect taxing a middle class. And it's principally the middle class that's already in financial trouble.

MOYERS: You tell a story that to me illustrates what has happened to our political system in regards to the middle class, in regards to democracy in the country as a whole. And it involves Hillary Clinton.

WARREN: I had written an op-ed about a piece of pending bankruptcy legislation. The credit card companies have been pushing to try to tighten the bankruptcy laws, sort of like locking the doors to the hospitals and then claiming nobody's sick in America.

So, they were trying to get the bankruptcy laws constrained, constricted, so that fewer families could get in. Why? Because you can make more money if those families don't go into bankruptcy, if you're a credit lender.

And so I'd written an op-ed about how this would fall disproportionately hard on women who were raising families and who would be put in the position under this bill of trying to compete with Citibank, MasterCard, Visa, Bank One for getting alimony and child support from their ex-husbands.

Mrs. Clinton evidently saw…

MOYERS: The First Lady then.

WARREN: The First Lady. She was then First Lady. This is the 1990s. Late 1990s. Mrs. Clinton saw the piece, and I got a call from the White House. And they said Mrs. Clinton was going to be in town to give a speech in Boston and would I come and meet with her. I said, "Sure."

And so I put together all my files. I show up at the appointed place. After she's finished her speech, we're ushered into a tiny, little room somewhere in the bowels of this hotel, and just the two of us. They close the door. Mrs. Clinton sits down. We have hamburgers and french fries.

MOYERS: You tutor her.

WARREN: And she says, "Tell me about bankruptcy." And I got to tell you, I never had a smarter student. Quick, right to the heart of it. I go over the law. It's a complex law. Went over the economics. Showed her the graphs, showed her the charts. And she got it.

Within 20 minutes, she could play where the rest of it would come. Well, then that will mean this part's happened. That will mean this has happened. I said, "Yes, that's right." And at the end of the conversation, Mrs. Clinton stood up. She said, "Let's get our picture taken" which we did, and she said, "Professor Warren, we've got to stop that awful bill," referring to this bankruptcy bill that sponsored by the credit card companies.

So I left. She went back to White House, and I heard later from someone who is a White House staffer that there were skid marks in the hallways when Mrs. Clinton got back as people reversed direction on that bankruptcy bill. President…

MOYERS: That was supporting the industry. And because of her…

WARREN: President Clinton had been showing that this is another way that he could be helpful to business. It wasn't a very high visibility bill. And when Mrs. Clinton came back with a little better understanding of how it all worked, they reversed course, and they reversed course fast. And indeed, the proof is in the pudding.

The last bill that came before President Clinton was that bankruptcy bill that was passed by the House and the Senate in 2000 and he vetoed it. And in her autobiography, Mrs. Clinton took credit for that veto and she rightly should. She turned around a whole administration on the subject of bankruptcy. She got it.

MOYERS: And then?

WARREN: One of the first bills that came up after she was Senator Clinton was the bankruptcy bill. This is a bill that's like a vampire. It will not die. Right? There's a lot of money behind it, and it…

MOYERS: Bill, her husband, who vetoed…

WARREN: Her husband had vetoed it very much at her urging.

MOYERS: And?

WARREN: She voted in favor of it.

MOYERS: Why?

WARREN: As Senator Clinton, the pressures are very different. It's a well-financed industry. You know a lot of people don't realize that the industry that gave the most money to Washington over the past few years was not the oil industry, was not pharmaceuticals. It was consumer credit products. Those are the people. The credit card companies have been giving money, and they have influence.

MOYERS: And Mrs. Clinton was one of them as Senator.

WARREN: She has taken money from the groups, and more to the point, she worries about them as a constituency.

MOYERS: But what does this mean though to these people, these millions of people out there whom the politicians cavort in front of as favoring the middle class, and then are beholden to the powerful interests that undermine the middle class? What does this say about politics today?

WARREN: You know this is the scary part about democracy today. It's… We're talking again about the impact of money. The credit industry on this bankruptcy bill has spent tens of millions of dollars lobbying, and as their profits grow, they just throw more into lobbying for how they can get laws that will make it easier and easier and easier to drain money out of the pockets of middle class families.

MOYERS: You have some very original solutions to propose in this book that go beyond ideology. Both liberals and conservatives are talking about this book. I highly recommend to my viewers that they get THE TWO INCOME TRAP: WHY MIDDLE CLASS MOTHERS AND FATHERS ARE GOING BROKE WITH SURPRISING SOLUTIONS THAT WILL CHANGE OUR CHILDREN'S FUTURES by Elizabeth Warren and your daughter, Amelia Warren Tyagi. Thank you very much, Elizabeth, for being with us on NOW.

WARREN: Thank you for giving me the chance to talk to you.

MOYERS: The bankruptcy bill Elizabeth Warren calls the vampire that won't die has risen from the grave again.

For seven years the banking and credit card companies lobbied hard to get it, and last week, yet one more version of the bill passed the House. The Senate is now considering it before sending it to the White House for President Bush's signature.

The companies, of course, are reaping record profits by urging consumers to borrow more. At the same time, they have long wanted to make it harder for people of modest means to use bankruptcy to erase their debt. Well, this bill gives the companies what they wanted.

It will not surprise you to learn that banks and credit card companies are among the most generous of political donors, over $37 million in one election year alone.

They were the top two sources of campaign cash for this man, former representative George Gekas of Pennsylvania, who had taken the lead in pushing the House bill.

M.B.N.A. American bank is the second largest credit card issuer in the country, and the top donor to President George W. Bush.

One more postscript to this story: the WASHINGTON POST reported that the bill passed by the House is "salted with language benefiting landlords, condo owners, auto lenders, shopping center owners, and even entertainment companies." And I'm not making this up: some clever lobbyist even got a provision slipped into the bill that enables landlords to evict families during bankruptcy.

BRANCACCIO: If you want to come face-to-face with the economic pressures Elizabeth Warren is talking about, you need go no further than Michigan. Many workers in that state are getting clobbered by the long slide in America's manufacturing economy. One in five factory jobs has been lost there.

State democratic activists are ticked off that frontrunner John Kerry supported the North American Free Trade Agreement which shifted jobs from Michigan to Mexico.

And despite Saturday's caucuses — and the biggest pile of Democratic delegates at stake in the campaign so far — the candidates are not running TV ads and have barely visited the state.

So I did, along with producer Betsy Rate. The town is Greenville, where they make refrigerators, at least for now.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: Greenville, Michigan is about 45 minutes from Grand Rapids. It's pretty small and also pretty conservative, located just one congressional district over from the one represented by Gerald R. Ford, Republican, who went on to become president. Greenville is also home to a big Electrolux factory. They make refrigerators — not the line of vacuums we all know. Many Frigidaires are born in this building. Sears' Kenmore and other brands, too. But not for much longer.

MIKE HUCKLEBERRY: They make five of the 10 best selling refrigerators right here in Greenville, Michigan. We thought life was good and it was going on. And it just --- right out of the clear, blue sky.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: Just three weeks ago Electrolux announced it's closing its plant. In this town of 8,000 people, 2,700 jobs will be leaving. Some to South Carolina. Lots to a new plant to be built in Mexico. In a statement, the company explained that all its competition has or soon will have Mexican factories. At lunch this week at Huckleberry's Restaurant in Greenville, some Electrolux employees let me sit in as they finished off their soft drinks. They made it clear that the town did not take this news lying down.

ROBERT TURNBULL, ENGINEER: The government threw in, basically, everything they possibly could. The union threw in a heck of a lot. And at the last minute, they still said, "No, thank you."

DAVID BRANCACCIO: Greenville residents are now struggling to make sense of both economics and politics in the wake of the Electrolux decision. Both the plant closing and this year's political races are front and center at Huckleberry's restaurant, situated along Greenville's older commercial strip. Mike Huckleberry or Huck, as they call him, has owned the place for 12 years, and makes it his job to bring out lunch orders, bus dirty dishes each and every day and chat. This puts him in a unique position to gauge what delights and what ails Greenville.

MIKE HUCKLEBERRY: Well, they're angry and they're frustrated. And they don't understand it. What they don't understand is why our government would allow this to happen.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: In fact, it's downright impossible to nosh on ribs or a brownie sundae at Huckleberry's without reflecting on what'll happen when Electrolux closes for good. Because Huckleberry's also serves food for thought - its owner's political manifesto appears on every one of its placemats.

MIKE HUCKLEBERRY: "Dear politicians. In spite of continued raises and perks for yourselves, you have allowed NAFTA and unfair world trade policies to take its toll on hard working Americans, their families and the communities they live in, as well as our great community. In spite of it, we have news for you. Greenville is bigger than Electrolux."

DAVID BRANCACCIO: It's an American tradition - Tom Paine had his pamphlets, Matt Drudge has the internet and Huck has his placemats. So do his customers.

MIKE HUCKLEBERRY: People started writing on them on their own. I didn't have to-- prod 'em or anything.

Here's a great one.

"If middle class Americans cannot work and earn a living wage, they will no longer be able to fill the coffers of the highest paid executive. And we all suffer."

DAVID BRANCACCIO: And this just from a customer here at Huckleberry's?

MIKE HUCKLEBERRY: They just sat down and started writing it. It's incredible.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: As Huckleberry likes to say, he gets all "walks" in his restaurant line workers and plant managers all of whom eats off those placemats.

MIKE HUCKLEBERRY: They agree with them totally. I mean the man-- this isn't a blue-collar issue. This is a white collar issue too. Now the educated people are losing their jobs.

So where does somebody go with a high school education? What does he train for that isn't gonna be moved to China, India or Mexico? I don't have-- I don't know that.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: It's a frustration that's especially painful given the way the community snapped into action when confronted with the Electrolux plan.

WALKER: The way the group came together and the things we were able to put together into a package I became very optimistic.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: Lloyd Walker is Greenville's mayor and job he's been elected to off and on three times over the past three decades or so. WALKER: And we brought in engineers, we brought in architects, we brought in industrial designers. We got together with the union, the UAW.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: And for a town of only 8000 people, the task force drew up quite a package. Electrolux had calculated it would save 81 million a year by moving to Mexico, Greenville's offer was close. By the town's calculation just 8 million dollars short.

MIKE HUCKLEBERRY: Electrolux was asking for $81 million. And we came up with $73 million dollars in savings a year. And it still wasn't enough for Electrolux.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: Mayor Walker's final strategy was a heart-felt letter to a senior company official.

WALKER: I told him how the history of the plant in Greenville, how refrigerator manufacturing was the fabric of this community, something that we'd had for over 100 years. There are things that are intangible that ought to be considered.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: An Electrolux VP called back:

WALKER: His last words were — that eventually it will be decided on economics, not on emotions.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: Of course, economics does rule. On January 16th, Electrolux said it would close its doors sometime next year.

President Clinton signed the NAFTA in 1993, lifting tariffs and allowing both goods and factories to move across international borders at will. Greenville, Michigan is one place where the economic pain is becoming a reality. According to the U.S. Labor Department, the number of factory jobs in America has dropped by 2 point 6 million since the last recession began — roughly the same length as President Bush's term in office. It dropped 11,000 more just last month.

As it happened, the Greenville Electrolux plant received its sentence the very same day that the Bush administration unveiled its plan to support the beleaguered manufacturing industry. Among other things, the plan would direct the Commerce Department to "root out" unfair trade practices and ease taxes and regulation for companies hurt by trade policy.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: You've expressed a lot of frustration directed toward the federal government. I haven't heard much about Electrolux itself. It's based in Sweden. It owns the factory here. You've expressed surprise and disappointment, but you don't really pin the blame on them?

MIKE HUCKLEBERRY: I don't. Not at all. I don't know if they had a choice.

All of their competitors have already moved there. How do they compete in America when everybody they gotta sell against is already there at $1.57 an hour wage and they're paying $15 a hour? I blame it all on the federal government. Corporations that go there have to survive.

And the question that I've gotta ask is when they've eliminated all of these jobs, who's gonna buy their products?

DAVID BRANCACCIO: Who's gonna buy the refrigerators?

MIKE HUCKLEBERRY: Who's gonna buy 'em? The Mexicans aren't gonna buy the refrigerators. They make $1.57 an hour.

We're exploiting them.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: And sitting around the restaurant with Huck, you quickly get the sense that's the foreign policy that really matters here these days.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: But jobs and the economy can't be the only issues that you're hearing about as you circulate among your customers here in the restaurant. National security is a crucial issue. The war against terror. That must be something that-- that must be a key concern here as well?

MIKE HUCKLEBERRY: Well, certainly it is. But we're away from-- it-- you know we're away from big cities, so we don't feel the pressure that they might. But I'll tell you right now, in Greenville, Michigan, the number one issue is what are we gonna do about all of these jobs going.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: President Bush's proposed budget this week calls for more money to help workers retrain by linking industry with community colleges. In practice, Electrolux engineers see a variety of challenges.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: What would you do?

ROBERT TURNBULL: Well, I'm looking at my options right now. Thinking about going back to school, going into teaching. Just kind of sittin' back and looking slowly. Really don't want to leave this area. This is my hometown.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: If you have to go into teaching, are you concerned that your standards of living would have to change in some way?

ROBERT TURNBULL: Oh, yeah. We're - we're prepared for the financial change I think the biggest problem is the classes that I have to take are day classes.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: Make that day classes, a partime job at nights, and in all likelihood, lower take-home pay.

ROBERT TURNBULL: I don't know. I gotta see if it's financially feasible to basically go hungry for three years. And I don't know. I can do it. But my kids get kind of cranky.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: Others are feeling more than cranky. Federal Mogul, a car parts manufacturer, announced last week that it could lay off 310 workers in Greenville.

Still, Mike Huckleberry, who's active with the local Chamber of Commerce remains tenaciously upbeat. He saw how another Michigan town is in the running for a new Boeing factory because it had recreation, a hospital, a good school system.

MIKE HUCKLEBERRY: And I said "You know what? Some good manufacturer out there is gonna say, "Geez, I'd love to live in a great community like this, surrounded with lakes and golf courses and a work force like that. And maybe this would be a great place to put a plant."

DAVID BRANCACCIO: Well, forgive me for asking personal political questions, but I hear Chamber of Commerce. I figure GOP, Grand Old Party. You a Republican?

MIKE HUCKLEBERRY: No, I'm not. I'm one of a few Democrats in this community. But saying that, I wanna-- point out I vote for good Republicans. I'm not a straight ticket puller.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: What do you think about how the economic stresses on this community right now, how that'll play out on election day? Either at the caucuses or perhaps in November? Do you think it's causing people to reevaluate how they vote?

MIKE HUCKLEBERRY: I get the feeling from a lot of people that are good conservative Republican are dismayed-- by President Bush's support of-- NAFTA and other un-- word-- unfair world trade policies. And they're frustrated with it. And I've had several of 'em point out to me, "This isn't what I voted for. I didn't vote for all the jobs to go across the border. This is-- has nothing to do with my good conservative values." They understand that a working man has to make a living. That we have to have industry. And they're seeing that-- not being eroded. It's eliminated.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: If all politics is local, the economic pain in this community is transforming the political perspectives of both parties this election year. Greenville's longtime Republican mayor.

WALKER: I can say that I've never voted for a Democrat for president, I've never voted for a Democrat for governor, I'm having some second thoughts.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: Mike Huckleberry will be taking a rare break from his restaurant for something unprecedented.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: So you have a caucus coming up here -

MIKE HUCKLEBERRY: Saturday.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: -- as a Democrat. You -

MIKE HUCKLEBERRY: Saturday.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: --- going?

MIKE HUCKLEBERRY: Yes, I am. I'm gonna be honest with you. I've never voted in a caucus before.

DAVID BRANCACCIO: This is your first time?

MIKE HUCKLEBERRY: This is my first time. I feel very strong that because of NAFTA and everything that's going that -- that - I've gotta vote in the caucus. So I'm looking forward to it. It'll be this Saturday.

ANNOUNCER: Next week on NOW: From coast to coast, the airwaves thunder each day with the sounds of right-wing talk radio.

DJ: Vaguely French-looking and botox-denying John Kerry winning and saying that.

ANNOUNCER: Where do their talking points come from?

RANDI RHODES: How in the world could you turn on five different shows and they're all talking about the same thing that day. How is that possible?

ANNOUNCER: An inside look at talk radio… next week on NOW.

ANNOUNCER: And connect to NOW WITH BILL MOYERS online at pbs.org.

More facts about economic stress on the middle class. See how elections are tilted towards incumbents. "By the People" 2004: Learn about the election year issues that matter most to you.

Connect to NOW at pbs.org.

MOYERS: After hearing David's report from Michigan, you can certainly understand why democratic voters there are grumbling over being slighted by the candidates.

After all, in Iowa and New Hampshire, voters would get a knock on the door and there would be a candidate introducing himself again. No more.

In the big states ahead, as a candidate you hope for lots of news coverage — what we call free media — and the money to buy TV spots that become your surrogate.

With more and more voters to reach and time running out, the TV commercial becomes the weapon of choice. Candidates will tell you, you can't do without them. With a TV spot, you can shape, shine and send the message you want to send, on your own terms.

As you'll see in this report produced by my colleague Brenda Breslauer, the TV commercial has changed American politics.

MOYERS: Some of us are old enough to remember the early days of political advertising on television. It was the 1950s, and General Dwight D. Eisenhower ran for President with animation by Disney and a campaign jingle by Irving Berlin.

His opponent, Illinois governor Adlai Stevenson, countered with a siren song of his own.

These early campaign ads could be critical…

Chirpy, feel-good, and positive….

…or scathing and negative.

Political ads came to define the candidates and their opponents as well as a campaign's message. The positive ones got slicker and slicker…

…and the negative ones nastier…

…and nastier.

North Carolina's conservative senator Jesse Helms ran this ad in 1990. "Nasty" worked; he won reelection.

Today, political TV ads show up in just about every competitive congressional race in the country. Sales have gone from an estimated 53 million dollars' worth in 1970 to a projected 1.3 billion dollars for this year.

STRUBLE: For my clients, if they don't spend at least two-thirds of their money on radio and television, they're misspending their money. They're increasing the likelihood they're gonna lose.

MOYERS: All this advertising is turning democracy into commerce and candidates into money-chasers, says at least one top Democratic media consultant. Karl Struble has watched it happen during his twenty years devising strategies for congressional and gubernatorial candidates and seeing costs skyrocket.

STRUBLE: No matter if you go to the smallest state in America these days, they're multi-million dollar races.

MOYERS: Louise Slaughter wants to slow down the money chase. She's been a Democratic representative from upstate New York for eighteen years, and she says television ads are replacing old fashioned grassroots contact with constituents.

SLAUGHTER: When I first ran, everybody had headquarters. They were able to have bumper stickers and buttons, and billboards and radio.

But no more. By the time I ran for Congress in 1986, we knew already that if you weren't on television, you weren't real.

MOYERS: In her last campaign, Louise Slaughter had almost a million dollars to run for reelection. A huge chunk of it had to go to television, she says, because her district had been redrawn.

SLAUGHTER: This last campaign was a new one for me, in that I got a brand new district, which was 60 percent new.

So, I had 60 percent of the people who've never heard of me. So, we spent $500,000 on television.

GOLDSTEIN: When you figure that out per voter and per time that a voter sees a message, it's actually not that expensive.

MOYERS: Ken Goldstein teaches political science at the University of Wisconsin and tracks TV campaign ads for the Wisconsin advertising project. Whatever their shortcomings, he says, political ads enable voters to know something of candidates they'll never see in person.

GOLDSTEIN: If Louise Slaughter has this new district, and she's gonna introduce herself to the district, sure, in a perfect world, we'd like her to be able to go walk every single house in that district. That's not possible. Even if it was nice weather in Rochester, New York, that's not possible.

The most efficient way for her to communicate with these voters and for them to get that little nugget of information about her and even more than a little nugget of information about her is through political advertising.

MOYERS: Maybe so, says Louise Slaughter. And she certainly knows how to uses ads effectively. Still, she laments how they reduce politics to photo ops. This ad is from her last campaign.

SLAUGHTER: It didn't tell anybody who I was or what I stood for, anything about my record. It just was the usual thing. Picture Louise with senior citizens, picture her in a diverse group.

See her walking on the street with a young family. The same ads I've been doing every two years now forever, and if you complain about it, they'll tell you, you don't know what you're talking about.

MOYERS: Louise Slaughter won that race with 63 percent of the vote.

But even if the half million dollars she spent on TV did the trick, Slaughter doesn't think that's where her supporters' money should go.

SLAUGHTER: I remember when I first ran in '86, a woman sent me a $10 bill stapled to a postcard. She lived in Seattle, and she said, "You're getting my contribution this year." I mean, people really work hard for you, sacrifice for you.

And their money shouldn't be spent that way.

MOYERS: And where do those campaign contributions go? Mostly to local television stations.

STRUBLE: The cost of production and consulting are really probably less than 10 percent of what it costs that they put on the air. So 90 percent of the dollars that you see in television have the, you know, you've seen your TV ads, are not on the production side. They really go into the TV stations.

MOYERS: He should know. Karl Struble oversaw about 20 million dollars worth of TV buys for his clients in the last election cycle. He says while that's good for his business, it comes at a high price to democracy.

STRUBLE: The rates go up and up as demand or how tight the race is. You know, I've seen rates double as you get in the last couple of weeks of the campaign. And what that effectively does is it mutes the voice of less well off candidates.

MOYERS: Which brings us back to Louise Slaughter and her efforts to do something about it. She tried repeatedly in the 1990s to require broadcasters to give something back for their use of the public airwaves…to no avail.

Then in 2002, she supported a provision of a bill demanding broadcasters offer candidates commercial time at reduced rates.

The provision was struck from the bill.

SLAUGHTER: Broadcasters are the strongest lobby in Congress. Members are afraid of them. They have the ability to punish you. They often set the tone in the town in which you live and I think there's that innate fear. "I'm not gonna rile these people up. They may do me some harm."

MOYERS: Yet even as the industry goes on raking in big profits from political ads, little of that goes into covering public affairs. Karl Struble says he can barely get his candidates' positions on the air unless he buys the time.

STRUBLE: You know, local TV stations, you literally gotta strip naked and set your hair on fire to get 'em to cover anything about policy. If there's a scandal, they might cover you if you're a politician. But they won't cover you if you're talking about policy.

MOYERS: That's why a chance encounter with a TV ad may be all voters learn about a political campaign.

STRUBLE: We can't force them to read the newspaper. We can't force them to go to Web sites. We can't force them to go to watch debates.

Passively while they're watching other shows, they get little bits of information, little vitamins of political information in terms of political advertising. I think that's helping at the margin.

MOYERS: So even candidates with reform on their mind have to learn to use commercials to their advantage. Earlier in Louise Slaughter's career one of her opponents went on the attack.

But Slaughter gave as good as she got.

SLAUGHTER: I did one ad once that I was really proud of. I was running against a multi-millionaire. And he had an ad with some really… the finest women in my district, saying that they used to like me.

But they believed that I have changed. And so, they're not gonna vote for me anymore. And I insisted on talking to the camera and saying, "Look. I'm the same Louise I was when you first sent me to work for you. If I could change, the one thing I'd be is thinner" I could tell in two days that the tide had turned. It was honest. It was me. I was talking to people. It was… I… but I had to insist on doing it.

GOLDSTEIN: Advertising matters at the margin. You think Al Gore wished that he would have spent a couple hundred thousand more dollars in Florida in 2000?

We're in a very evenly matched political time in this country.

MOYERS: The result, says Louise Slaughter, is that campaign ads and the chase to raise money for them have become the necessary evil of American politics.

SLAUGHTER: At the same time, I'll tell you, if I'm not on that television, nobody takes me seriously. And we have to compete with everything in the world, just to try to get the voter's attention.

BRANCACCIO: As the candidates and their campaigns dash across the country, we've been taking a look at how people connect to the political process.

A couple of weeks ago, NOW dropped by the Conservative Political Action Conference in Virginia. Tonight we check in on a new trend in grassroots organizing.

BRANCACCIO: In Kansas City, people have come together to put on what looks like a county fair. They'll set up stands for food and stages to hear live music, but they have ambitions way beyond a Saturday afternoon pastime. They want to reinvent politics.

CHEATUM: Well, corporations and big government have taken us over and this country is founded on the people and the populace and we want to have that again. So that's why we're having this. We're going to take back America.

BRANCACCIO: How does one take back America? People here say you have to put the party back into politics.

That's the mission of the Rolling Thunder Down Home Democracy Tour, a series of one-day festivals that bring together people who want to connect with democracy.

Like many efforts to invigorate politics, it's not quite setting the world on fire. But, the founder of Rolling Thunder says you have to start somewhere.

HIGHTOWER: The idea of Rolling Thunder comes from nature. I grew up in north Texas, northeast Texas. And there, the Rolling Thunder is a national phenomenon. It is the harbinger of the rains that green up the grassroots and let the flowers bloom. And in this case, we're talking about the flowers of democracy.

BRANCACCIO: Jim Hightower used to be the Texas agricultural commissioner. Now he's an author, radio commentator and a national rabble-rouser who calls himself America's #1 populist.

His latest book, THIEVES IN HIGH PLACES was a bestseller.

Hightower says that people come out to Rolling Thunder because they feel that politics is not speaking to them.

HIGHTOWER: People are yearning to meet each other. And not just high tech, but high touch. To actually be in touch with each other. And to talk back. And what if we all got together?

BRANCACCIO: Every Rolling Thunder event has tables and dozens of workshops on all sorts of issues, from campaign finance reform, to protecting civil liberties…

The goal is to let people learn from each other about local and national issues…as well as alternative ways of getting things done.

MAN: The antifreeze line right here is running next to the vegetable oil, so they heat it up. And as soon as it's warmed up, you hit the switch and it goes to the vegetable oil. And it goes zoop, zoop, zoop, into your fuel injector.

WOMAN: My job is racial justice, so I work with different populations.

MAN: Small scale neighborhood credit unions instead of a giant, massive…

MAN: Just so money within the neighborhood stays within the neighborhood.

REGGIE: So tie in this these workshops, make a commitment to one of these groups, and get your email on that list so that other people can find you.

BRANCACCIO: The inspiration for Rolling Thunder came from a movement that began in 1874 on the banks of Lake Chautauqua, New York. There, families would camp out every summer to hear speakers and music, put on plays, and engage in open forums on philosophy, literature, art, religion and science. Chautauquas, as they were known, became so popular, they went on the road. And at their peak in the 1920s, they attracted at least 10 million people a year.

Jim Hightower saw the potential in creating a modern day Chautauqua, but one with agitators in the mix.

Like filmmaker and author, Michael Moore.

MOORE: You guys all just gotta do it!

BRANCACCIO: Congressman Jesse Jackson Jr.

JACKSON: All Americans deserve the right to a public education of equal high quality.

BRANCACCIO: And columnist Molly Ivins.

IVINS: Y'all need to have more fun.

HIGHTOWER: Agitation is what America is all about. Were it not for agitators, we'd be wearing white powdered wigs singing God Hail the Queen here this afternoon! America was built by agitators!

BRANCACCIO: There's no question that there are plenty of agitators on hand. But after the tents and tables are put away, it remains to be seen if people will go home and reinvent politics.

MULKEE: I think that one of the benefits of getting together like this is to see that there are more of us than we think there are. You know. Even if it is preaching to the choir. You know. That's ok. There's a time for that.

MOORE: And I think people are gonna go from here and do… go back to their towns, go back home and do something. Not everybody. It doesn't have to be everybody.

Just need one Rosa Parks that was here today. That's all we need.

BRANCACCIO: What kind of impact will Rolling Thunder have on the political landscape? Stay tuned. So far, 68,000 people have turned out to the events across the country…

From Seattle, Washington to Asheville, North Carolina. And there are six more cities planning festivals this year.

HIGHTOWER: Politics ought to be part of your life. It's not something that is just in the last thirty days of an election.

But the whole idea of a Rolling Thunder Down Home Democracy Tour is to be festive, and mostly for you to enjoy it, and to think, "Hey, this isn't bad. If this is what politics is, I could do this."

BRANCACCIO: A final note. This week, President Bush asked Congress for $401 billion in military spending for 2005. That's a 7 percent jump over this year. Now, that is an increase that brings him close to the Reagan era military buildup.

The budget is silent on money for military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. This Web site, costofwar.com, lets you check the cost of the war yourself.

President Bush will let us know how much supplemental money he'll need to pay that bill after the elections.

MOYERS: And that's it for NOW. If WALL STREET WEEK follows our show in your city — as it does on many stations — our friends there are tracking how money flows into political advertising.

David Brancaccio and I will be back next week.

I'm Bill Moyers. Good night.

© Public Affairs Television. All rights reserved.

- Series

- NOW with Bill Moyers

- Episode Number

- 306

- Segment

- Campaign ads

- Segment

- Job loss in Michigan

- Contributing Organization

- Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group (New York, New York)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip-36cc10b7714

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip-36cc10b7714).

- Description

- Series Description

- NOW WITH BILL MOYERS: A weekly news magazine, reported in conjunction with NPR, includes documentary reporting, in-depth one-on-one interviews, and insightful commentary from a wide variety of media-makers and those behind the headlines.

- Segment Description

- Bill Moyers goes in-depth with Harvard Law professor Elizabeth Warren who reveals some surprising facts about the plight of America's two-income families.

- Segment Description

- NOW profiles Jim Hightower's Rolling Thunder Down Home Democracy Tour that is helping energize citizens about politics. Political candidates are relying on advertising to reach voters, even as the costs to air these ads have grown significantly.

- Segment Description

- NY Congresswoman Louise Slaughter discusses the burden of political advertising.

- Segment Description

- David Brancaccio travels to Greenville, outside of Grand Rapids, where just a few weeks ago, the factory manufacturing Electrolux refrigerators announced that it was closing next year. The move will cost 2,700 jobs in a town of just 8,000.

- Segment Description

- Credits: Director: Mark Ganguzza; Line Producer: Scott Davis; Coordinating Producer: Irene Francis; Interview Development: Ana Cohen Bickford, Gina Kim; Editorial Producer: Rebecca Wharton; Interview Producer: Megan Cogswell; Producers: Bryan Myers, Keith Brown, William Brangham, Brenda Breslauer, Peter Meryash, Betsy Rate, Na Eng; Writers: Bill Moyers, David Brancaccio, Judy Stoeven Davies; Editors: Larry Goldfine, Vincent Liota, Alison Amron, Amanda Zinoman, Kathi Black; Production Manager: Ria Gazdar; Senior Associate Producers: Carol Atencio, Karla Murthy, Candice Waldron, Jennifer Latham, Elena Bluestine; Associate Producers: Stefanie Hirsch, Rasheea Williams, Dan Logan, Rachel Webster; Production Associates: Kristin Burns, Ismael Gonzalez, Renata Huang, Mariama Nance, Avni Patel; Mao Yao, Tua Nefer, Titu Yu, Moss Levinson; Production Assistants: Lisa Kalikow, Reed Penney, Joshua Wolterman, Anna Melin, Ceridwen Dovey, Amelia Green-Dove, DongWon Song, Matthew Harwood; Interns: Emi Kolawole, Marshall Steinbaum, Aaron Soffin, Eileen Chou, Creative Director: Dale Robbins; Graphics Producer: Abbe Daniel; Graphics: Chris Degnen, Liz DeLuna, Gregory Kennedy; Music: Douglas J. Cuomo; Senior Supervising Producer: Sally Roy; Executives in Charge: Judy Doctoroff O’Neill; Co-Editor: David Brancaccio; Executive Editors: Bill Moyers, Judith Davidson Moyers; Senior Producers: Tom Casciato, Ty West; Executive Producer: Felice Firestone; Sr. Executive Producer: John Siceloff; Correspondents: David Brancaccio, Deborah Amos, Daniel Zwerdling, Rick Karr, Michele Mitchell, Roberta Baskin

- Segment Description

- Additional credits: Producers: Naomi Spinrad, Paul Stekler, Katie Pitra, Daniel McCabe, David Grubin, Robe Imbriano, Sherry Jones, Leslie Sewell; Writer: Sherry Jones, Kathleen Hughes; Associate Producers: Blair Foster, Hilary Dann, Cope Moyers; Editors: Rob Forlenza, Lars Woodruffe, Kathi Black, David Kreger, Alexandra Yalakidis, Laurie Wainberg, Bob Eisenberg, Nobuko Organesoff, Jeremy Cohen, Andrew Fredericks; Jeremy Cohen, Alex Yalakidis, Win Rosenfeld, Dan Davis; Correspondents: Robert Krulwich, Rick Davis, Sylvia Chase, Juju Chang, Jane Wallace

- Broadcast Date

- 2004-02-06

- Asset type

- Episode

- Genres

- Magazine

- Rights

- Copyright Holder: Doctoroff Media Group LLC

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:58:16;03

- Credits

-

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group

Identifier: cpb-aacip-2de767cc2aa (Filename)

Format: LTO-5

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “NOW with Bill Moyers; 306; Elizabeth Warren on two-income families; Campaign ads; Job loss in Michigan,” 2004-02-06, Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed September 7, 2025, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-36cc10b7714.

- MLA: “NOW with Bill Moyers; 306; Elizabeth Warren on two-income families; Campaign ads; Job loss in Michigan.” 2004-02-06. Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. September 7, 2025. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-36cc10b7714>.

- APA: NOW with Bill Moyers; 306; Elizabeth Warren on two-income families; Campaign ads; Job loss in Michigan. Boston, MA: Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-36cc10b7714

- Supplemental Materials