¡Colores!; 603; Building Bridges, Binding Generations: Hispanic Women and Their Art

- Transcript

I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry I want to create something

that will last, but even more important than creating an artifact, whether it's a book or a painting, is creating a place within myself that will last. Because in the end, Hispanic women are survivors. They show that in their politics, they show that in the art. I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry For me,

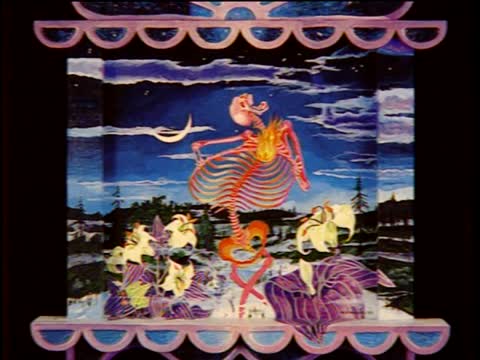

it's a kind of a meditation, and it's rooted in my Mexican ancestry. My grandfather was from Parachua, and Mexican culture has been for thousands and thousands of years very much tied in with ceremony and art that includes the image of death. And so I use the skeleton in my paintings because of these cultural reasons. I mean, it's a very powerful image because we all know that we all have a skeleton and that we will all die someday. It's a great equalizer underneath our culture and our races and our gender. We are all precious. I do lots and lots of dancers. And there's this figure, this female dancer that keeps coming through in the paintings. Dance is one of the oldest art forms, and it is a religious art form originally. And it was probably the

precursor of architecture in that in dance and in ceremony people oriented themselves to the universe, to the earth, to the planets, to the seasons, orienting ones, human consciousness. It's like the dance of life, too, and the dance of death, which are the same. I do lots of weddings. I have a wedding that's hanging in the permanent collection at the Albuquerque Museum, and the weddings are about the reconciliation of the conflict between the genders. Those parts of our psyche are supposed to blend and become harmonious and to balance one another. I like to paint themes. You know, I have a couple of Jewish theme. I have the dancers, and I'm doing another

series of paintings on the theme of Enjarrando. A technology that includes all of the embellishment and finishing of the Adobe architecture, all of the surfaces, the interior and exterior plastering, restoration and maintenance, the building of fireplaces, and the process of anisando, which is covering the walls with colored clay slips, the mud floors, the Adobe ovens, the ornos. In other words, all of the decorative and protective surfaces of the architecture were done by women, passed on by oral tradition from one generation of women to the next, beginning with Native American women, and passing on into Spanish culture, and that's what Enjarrando is. The architecture is maintained generation after generation. They have to pass on their traditions. The older plasterers teach the younger plasterers, so it becomes a focal point of communities. And for

years, I worked on churches. I never charge for any work that I do on religious structures and any denomination I worked on, mosques, synagogues, Catholic churches. That is my way of helping to perpetuate the sacredness of community, which is one of the most precious things we still have here in New Mexico. The series is the Dreams and Myth series, so what happened was I started to have this repetitive dream, and what the process was for me was that the dreams would come until I photographed them, and then after I photographed them, the dream would change into a new dream. So it was kind of a very internal process geared towards touching the subconscious mind more than the conscious,

the mythical part of our darkness, and a pursuit of the aesthetic that is not a pursuit of the aesthetic in terms of sculptured stylized bodies, in terms of a concept of beauty. Looking also at a very different concept of beauty, I'm looking at the beauty from the primitive, from the more primal, as opposed to a quote unquote, civilized or evolved culture. Modern society has really made an enormous effort to deal with comfort and all of this superficiality so that we don't think about our animal being. And which is actually kind of crazy because how do we explain all of this human behavior, if we don't consider the animal, the predator behavior, and when you look

at war, all the barbaric things that we do as a species. Mexican mythology talks about the presence of the tonal and the nawan, and in nawan is when we're born, we're all nawan, which means we're intact in a way, and as we civilize ourselves, and as we learn things, then the tonal starts to move in and take over. When we're children, when we're in the middle of the nawan, and we don't have that much tonal in us, we have this wonderful magical thinking. In cultures like in Mexico, you have still alive a lot of the magical thinking, and it's manifest in the wonderful Mexican arts and crafts, and in rituals and magical realism. It's magic within real life. For me, who is producing the work, the magic is to go through this wonderful process in which these

images came to me in dreams, and also a recognition of the wealth of stuff that is in there inside of me, the surrendering to the process, accepting that there is a light side, and there is a dark side, and there's that in our humanity also. And I think that the difference between my work and what Tundra can Harry does is that process, not to forget who I really am. For artists and for women who are cultural expressionists, I think the challenge becomes how do we protect our culture, how do we preserve the culture and cultural traditions, at the same time that we also move into the future, in such a way that the cultural expression is not only, maybe we'll reflect some of these changes, but we'll also challenge some of the more negative aspects of those changes. And provide even perhaps some guidance or some light as to how we can even look

positively towards the future. Nils Simon didn't write for a five foot to 99 pound Hispanic woman, and I didn't even know what stereotyping for the theater was all about. I just wanted to get more exposure, so I started to perform comedy, and I fell in love with comedy. And I think that within this umbrella term, Hispanic, that there's too much self -segregation. I don't know what we all have in common, I mean different foods, different parts of the country, but then I looked around, I studied, and I realized the women throughout the world, we all have something in common, Hispanic women. You know, we could be heads of our companies, we could drive porous, but we can't get rid of this little mustache, okay? For two years, I bombed, people booed a lot of my jokes, and I still did not

feel ashamed or afraid, and every week I'd keep going up because the only way to develop yourself in any area of whatever you're pursuing in your life is if you fall off that horse, get back on it again. And even then, you see comedy how you're assimilating as a comic in America. You've got to give it right, like I watched Jerry Seinfeld, Alan DeGeneres. These people, I've seen them, you know, bomb once in a while when they were first starting, but they also finally gave the formula right to get on TV, you know, they fit the right mold. Because I know so many good, good comics that will never, ever get on TV because they're too radical, social commentary, but they just don't, they haven't assimilated yet. Let's see, when I first came back to New Mexico, and I saw the exploitation of these women scantily clad women on billboards, advertising hooters, I said, oh, look at that. He has a restaurant. See, I don't know why they don't give us women a restaurant, right?

And caught peckers. I was doing these jokes about the stereotypes, the hubcaps and the maid, and I say, man, I have a college degree. I'm a smart woman. Why am I letting these people, you know, let me put myself down on stage. That's not the way it is. So when I came off more intelligently, and I people didn't seem to like that, though, that's where the obstacle is, not playing into the stereotype. But yet there is a side to my life that is the stereotypical Hispanic person's life. I think my life, when I talk about my life, some people get mad because they think just because I'm up there, I'm speaking for every Hispanic in the world, and that's a lot of responsibility for someone. People are afraid as a Mexican -American woman, I get censored right and let their afraid, oh, she might use the F word. Yes, stop. And I wonder, why do they censor me? You know what they should censor, the clothes, the people wear, right? You get these guys that walk around the state fair with their pants hanging about right here,

and they're not studying plumbing at TVI. I have three words for these guys, all right? Buy a belt. Then if you buy a belt and you feel the leather burning behind your knees, pull up your pants. Someone came up to me and said, you know what, Rosie Perez got your job. I mean, how did she get my job? I don't understand that, but see, she's a Latin woman, so now she's got that only spot in America out of millions of people to speak for the Latins in America. I don't understand how, why I have to get a little bob haircut to be a success in America. You know, why have to wear it loafers? Why can I wear my little stiletto heels, my red lipstick? You know, let me be me. Rosarita is sort of my alter ego. She's my radical side. She's the social commentary person that I really am, and she's a Latino woman. I mean, she

has a little rose. She puts in her mouth. She does the little dance. She does that little fantasy that lots of people think the Southwest is all about, but when she comes across, she's not saying, you know, come to my house for dinner. She's just saying, you suck. That's all her is doing. I don't like what you do to me and you suck. But I always have one guy after the show, looking me up and down, doesn't like what I say. And I have to respond. If you don't like what I say, hey, don't come to my show. Oh, dad. A comic makes changes. I think comics are just out there, and they just really are constantly battling the world in a whole different way, almost like a social activist. That's what my role is. I feel as a comic. When I first started working with the Mojitas Muralistas that came about

from my being at the Art Institute, the San Francisco Art Institute and getting a scholarship to go to school, and it was a dream come true for me in order for me to go. To be in the art school, and I was working already in the community helping students get jobs. So one of the priests in one of the schools asked me if I could, if I could do a mural on the wall, and I got on inspired, and I went back and talked to my girlfriends, and they were all excited because I think we were all needing to have a way to express our Latin culture. And we weren't finding a way of vehicle in which to express ourselves and our artwork at the San Francisco Art Institute, because coming from a Latin culture and the colors and the vibrant colors that we express weren't being projected in the classroom. So the minute I brought up the idea of us getting out there and painting murals, everybody was excited. The response was extremely positive. People were very happy

to see us working as women. In fact, they couldn't tell we were women until we came off the three -story scaffolding and they said, oh, you're women. Oh, I had no idea. What are you painting? What is it about? And they began to like our work also because we were more sensitive in the kinds of things that we were doing for the community. It wasn't just our own personal artwork, but we were serving the community. In other words, we were painting the images of the Latin community, the Latin culture, and that went with the music, the food, the smells. It was just beautiful. The struggles of being a Chicana women, woman artists is the message struggles. For example, my mom all she expires me to do was graduate from high school and get a job at the bank and look pretty and have a car and have clothes. She says, and then help her pay the rent and the bills because

she had already done her job. Her job was to get me through high school and anything after that I was supposed to give back. And when I told her I was going to college, she says, you're going to do what? She says, that's not for you. Mexicans don't go to college. It's only for white people. Didn't you know? And then I thought about it and I said, well, that's true. My girlfriends aren't going to college. Very few of my friends were going to college. Maybe she's right. But I said, listen, none of my family has ever gone to college. Why can't I? And I'll figure it out. I'll figure out how to get there. Actually, being in the school was very different from my upbringing. I had a real hard time fitting in. Most of the kids that went to that school were very rich, had a lot of money, had a lot of equipment, had the best brushes that money could buy. And I dug mine out of the trash can. Because these rich kids at the end of the semester threw everything

away because they were going to get new ones at the beginning of next semester. For me, it was like treasure. In fact, I still have some of those brushes. They were very fine brushes. You just take care of them. May last you forever. Keeps you growing is the fact that it's your spirit and your heart and humanity and the goodness of people. You're inspired to be an artist and you have to be an artist at any cost. And any cost means sometimes economics, jobs, you know, sometimes men, play a part, and sometimes children. If you truly are an artist, you can work in the closet. There's always something to work with. The inspiration is like this flame that burns inside of you. We have poets. We have writers who are writing

about tremendously important significant political issues like immigration or immigrants who are here, the disenfranchised. We have women who are writing about poverty, who are writing about their families, and perhaps to some extent the disfunctions in our various families. Celebrating also our cultural strength and survival. Because in the end, Hispanic women are survivors. They show that in their politics. They show that in their art. Well, mother tongue is really a long poem in disguise. Because after I graduated from Princeton, I had a degree in public international affairs. I really felt the calling to be a poet. And so I read and wrote poetry for about ten years. And that teaches one, if nothing else, to

listen deeply. And so I started writing it in fact in hotel stationery. And it was a nine month epiphany. I never felt that I was putting out the words. I felt that they were being given. You know, it's really just girl meets boy girls falls in love with boy. I mean, that's it. That is really the story. But as you begin to see their love embedded in a particular historical moment, which was the Salvadoran Civil War, then out of that emerges some of the political struggles. And ultimately, their own struggle as lovers, the differences in culture, the differences in language, his dream of going back to El Salvador up against her dream that they could marry and live happily ever after. During the years of my mother's illness,

or maybe years before, I fled the world, went inside, ceased to feel. You could say, I fell asleep. There was no mystery to it. Quite simply, it was easier to sleep and pretend to be awake than to stay awake and pretend to be strong. Twenty years later, I can say this without shame. They had words for women like me. Insane, fell out of favor, as did nervous breakdown. Clinically depressed was, I believe, invoked. But ask any woman who has had times in her life when she was not all there. She will say, she was asleep. And women who fall asleep and don't know why. Lack of plot line. This is the secret source of their shame. So I concocted a plot of my own, orchestrating what I could until characters began to say and do things I never imagined, me included. To prove the gods at least were interested in me, I courted disaster. Set out to love a man I knew full well would go away. Falling in love was a way of pinching myself. It proved that I was alive if only on that thin line

between drama and trauma. I handed my body over to Jose Luis like a torch to help him out of his dark places. I felt no shame. I was utterly unoriginal. To love a man more than oneself was a socially acceptable way for a woman to be insane. The book is also about what I would call personal and social healing. It asks the question, what does it take, what will it take for individuals who have been violated in some fundamental way, either through childhood abuse or through torture as a political prisoner. But key to that is memory. When we find a place to light a candle to what we can't ever recover, what we can't remember, what can't be brought back that that too is part of being human. It has

taken me this long to move beyond the resentment I feel it having told you the part of the story I had intended to keep to myself. Resentment, because I'm telling you, whoever you are, I open the wound. I told myself the part of the story I had hoped to keep from myself, the disappeared part. But the unspoken words were turning into hooks that were caught in my throat. Once a story has begun, the whole thing must be told, or it kills. If the teller does not let it out, the tale will seize her, and she will live it over and over without end, all the while believing that she is doing something new. The great circle will come to represent not life, but stagnation, repetition. She will die on a Catherine wheel of her own making. Through the writing process, at age 39, as she reflects upon this love affair, she tells the story of how she finally came to remember, to recover that part of herself that had been disappeared as a result of this childhood

violation. It's good that I know what I know, because it helps me be more compassionate towards Jose Luis. I think a part of me envied him. It's a terrible thing to admit. When he gets up to talk and pack churches, his wounds are deep as the Grand Canyon, open to everyone. Mine have always been invisible. I mean, it's not like I can stand up in front of a crowd and talk about something as dumb as sadness, or fear, or being abandoned, or life spinning out of control. It's not on the same scale as death squads and disappearances, or rich people owning all the land. But the issue isn't who got hurt more, I keep feeling like it's all part of the same pattern of people loving power, or some such thing, more than life. I want to create something that will last, but even more important than creating an artifact, whether it's a book or a painting, is creating

a place within myself that will last. Is the idea that we have a place to go into, that no one else can come into, except the spirit, and that that place will last. And that's where the art comes from. The art is secondary to the creation first of that inner room. The path of life is not important, the path of life is not worth it. The path of life that we have a place to go into, that path of life is not worth it. I just

want you to love me, I just want you to love me. This colores program is available on Home Video Cassette for 1995 plus shipping and handling to order call 1 -800 -328 -563. Thank you.

- Series

- ¡Colores!

- Episode Number

- 603

- Producing Organization

- KNME-TV (Television station : Albuquerque, N.M.)

- Contributing Organization

- New Mexico PBS (Albuquerque, New Mexico)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip-191-32r4xmd1

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip-191-32r4xmd1).

- Description

- Episode Description

- An insightful probing of the art and experience of a number of Hispanic women who examine their roles in their communities; in their relationships with men, their families, and their culture. They also consider the larger social milieu with Anglos, African Americans, Native Americans, and other ethnicities among whom these Hispanic women will soon be in the majority. Featured Segments: Ancestors Calling: Rooted in Mexican Culture, Anita Rodriguez (Painter, "Enjarradora" or Mud Specialists/Adobe Finish); Primal Beauty: Not to Forget Who I Am, Cecilia Portal (Photographer, Series - "Dreams and Myths"); Standing Alone: Let Me Be Me, Goldie Garcia (Comedienne); Poetic Perseverance: Art at Any Cost, Patricia Rodriguez (Mujeres Muralistas); Return Home: Creation of That Inner Room, Demetria Martinez (Author, "Mother Tongue"). Guests: Anita Rodriguez, Cecilia Portal, Theresa Cordova (Chicana Studies Scholar), Goldie Garcia, Patricia Rodriguez, Christine Sierra (Chicana Studies Scholar).

- Description

- No description available

- Created Date

- 1995-02-01

- Asset type

- Episode

- Genres

- Magazine

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:28:07.953

- Credits

-

-

Guest: Cordova, Theresa

Guest: Rodriguez, Patricia

Guest: Garcia, Goldie

Guest: Sierra, Christine

Guest: Portal, Cecilia

Guest: Rodriguez, Anita

Producer: Mendoza, Mary Kate

Producing Organization: KNME-TV (Television station : Albuquerque, N.M.)

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

KNME

Identifier: cpb-aacip-db21a6b83d6 (Filename)

Format: DVD

Generation: Original

Duration: 00:30:00

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “¡Colores!; 603; Building Bridges, Binding Generations: Hispanic Women and Their Art,” 1995-02-01, New Mexico PBS, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed February 17, 2026, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-191-32r4xmd1.

- MLA: “¡Colores!; 603; Building Bridges, Binding Generations: Hispanic Women and Their Art.” 1995-02-01. New Mexico PBS, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. February 17, 2026. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-191-32r4xmd1>.

- APA: ¡Colores!; 603; Building Bridges, Binding Generations: Hispanic Women and Their Art. Boston, MA: New Mexico PBS, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-191-32r4xmd1