¡Colores!; 1103; Gustave Baumann

- Transcript

You You You You

You You You You You You You You You This coloris is funded in part by New Mexico Arts, a division of the Office of Cultural Affairs. His hands were large. Of course, he could do very delicate work with them. His heart? Well, I think it was bigger than he let on. Hands of a craftsman, heart of an artist, Gustaf Balman in New Mexico. Gustaf Balman in New Mexico. Gustaf Balman in New Mexico. New Mexico is an easy place to call home.

When I first saw Santa Fe, the old part seemed to be like picture books stuff that somebody had dreamed up, and then it found it comfortable to live in. If you like the Taus country, it is fatal to stay too long because you'll never feel at home again anywhere else. Given a free choice in the matter, I would have selected this off-west as a place to be born. I would have learned Spanish, along with riding the horse and predicting the weather. If you like the video, please subscribe to my channel. I mean you have the way to win this thing,

those of me who lost their games, but are you lost? N-no, not me, either. No, no, no. You won't do me皮. I told you, okay, let's go. Where do I go, Ollie, okay, I said, well, hold it up, I'll give life to you! I can just give life to you. Cheers, obviously. Oh, okay, go. Focus, buddy. Do you? Ain't like me, Hey, don't forget me, I'm taking the scenic route. Hey, hey, wait, come on, wait for me. He was a very pleasant fellow. Many times he came down to our shop and he always seemed to be smiling. Even when he wasn't laughing or smiling, it appeared to me that he was smiling. To start the week right for everybody, I was born of a Monday and introduced by the usual number of parents to their fellow residents of a small North German city. Our family lived in one of those narrow houses, pinched in between others seemingly dating from the Middle Ages.

Not quite as picturesque as some I've seen on German postcards, but the dank atmosphere surrounding it was identical with that of the best of them. My mother, with an eye to the future of her children, dreamed of America. We embarked on a liner with a band playing heirs of farewell songs. A bundle of drawings made at odd times with determination to become really useful, received from me an apprenticeship in an engraving establishment which required my working gratis for a long period with the privilege of sweeping the establishment and running errands. Changing jobs was no solution, so I found it advisable to remove my drawing board in color box to a small studio of my own where I worked hard and in between times grabbed fragments of the education I had missed in earlier years. Since I am fundamentally a craftsman, the print was for me a way out of a blind alley.

While there was a great deal of uncertainty, my direction was never disturbed, not even by an accidental interview with a friendologist, who with his glasses pushed back over his respiring forehead, solemnly calipered the bumps on my head, and then gave me a complete chart to prove why I would make a good doctor or eye surgeon. The creation of that perfect thing we recognize as art is given to all two of us. When it happens, it transcends time and is rightly included or added to the treasures that have stirred the imagination of past centuries.

But art is a kind of tyrant. It came to me dressed up in wanderlust. Tickets please, who wants to go? A rolling stone said I. Where to? Touse said I. Hop on rolling stone and remember me to Mabel when you get there. The conductor on the Denver and Rio Grande narrow gauge had a lot more to say on the way up the river before he dropped me off at Touse Junction. There is no mountain so tall as when you see it from level prairie ground. There it is, bathed in inscrutable blue. The train engine gives a whistle as if the engineers saw it too. While it is an old story to him, the passengers feel as if they're getting somewhere different from where they've been,

and read the railway folder for perhaps the tenth time. They reset their watches from standard to mountain time and glue their noses to the windows. To have dreamed about Touse for years and then one fine day actually waking up in it made me wonder. The sounds of voices that came over the trance and were strange even the silence was of a different sort. What I saw and felt at the time had no relation to my earlier notion of the great American desert. People actually lived here and what appeared more strange they spoke Spanish and several Indian tongues and they seemed to be long much more than I or my Eastern friends. It was no desert. Here were friendly and intensely green fields between immense stretches of soothing loneliness. Where if you greeted a passing fellow man you could do so without injuring his toes or chafing your elbows.

The houses looked as if they had been pushed up out of the ground to have a roof clapped on them. It looked like something out of biblical history that had been preserved all these years. When I first came of course I met them before I had well just about the time I suppose that I met my husband to be. Gus had made a very lovely painting which he suggested to John that he hang in the house that he was building which had very big spaces and a very nice living room. Gus said why don't you take that painting and hang it over the fireplace it would look good and if anybody wants to buy it it's a sale. And so the morning that we were to get married at the door of John's house arrived a messenger with a very scruffy little bit of paper in his hand. I think it was a boy and a little boy and it was just a piece of paper torn from a little notebook and it said keep the painting, love, Gus.

And so it was just an incredible start to our married life as you can imagine. They have such a work of art and so much kindness behind it from such a special person. I became painfully aware that summer was drawing to a close. I had investigated the mountain and desert and all the fascinating corners of toast but learn too late that a pallet and theories regarding color east of the Mississippi should all be tossed in the river as you cross on the bridge. Hand and heart logo which is the one he used the most reflected some of his philosophy about art. The hand represents the art that is produced but it's the heart that motivates the artist to do that.

He was careful to price his art so that anybody who wanted it regardless of their income could have it. I think he felt that everybody should have a bit of art in their house. Seeing the long mountain range from the distance always makes me wonder what is back of it. This particular range had a road through it that led to Santa Fe if you were in no hurry to get there. In those days there were three cars that stood up to the problem. One was that funny old Ford, then the Dodge and the Cadillac. We made it in the Ford after throwing a ceremonial kiss to Tauce. There was no heavy cloud of smoke overhanging Santa Fe to indicate its presence when there it was as if hiding in pinions and cedar bushes. Unconsciously I gravitated to the plaza.

A brilliant sunset hung over the mountains. Blackshold women were going on unhurried errands and cowboy boots clicked everywhere. Martin Gardesky was selling exotic perfumes in his drugstore to surprised Eastern ladies and the bank saloon was functioning solemnly as a soda fountain. I almost forgot going into the art museum. I made it just before closing time. He was dead serious about art. He was very flexible. He was interested in modern art. He very interested in Max Ernst took a trip to Arizona to meet him one time. I'd say he's very eclectic in his view on art. He was willing to consider what the person had to offer and then made his decision. The little home I lived in is still there on a little flat iron corner where Garcia joins Canyon Road. It had a white picket fence that enclosed a garden where zinnias and merigolds grew rampant.

My mother and I met at San Felipe Pueblo in December of 23. She had come down from Denver with some friends. She came down to Santa Clara Pueblo. She was very interested in Indian songs. So through an anthropological friend in Denver, she made arrangements to stay with a family in Santa Clara Pueblo. During this time, she and I saw each other several times. He offered her the house to come in and take a bath if she wanted to. She was such a personality. When she was on the stage, she did get to be sometimes and of course she had been an actress.

But it was hard to see anybody else because even though she was a very generous actress, she was just such a personality that she could really just be a magnet for the audience. The Marinettes of course were very much a part of our life and the stage was there in the living room and the Marinettes hung on a rack behind. You had the physical presence all the time to wait for hours a day of that stage in the Marinettes. People when they sometimes would come to visit, mother would be asked to show them. She would bring one or two figures onto the stage. When I was growing up at Christmas time, we had the Christmas shows, which took over the whole house. I love the Committee of Del Arty ones, the Columbine and Pierrot.

I hated Hallocken because he was mean. And boom, boom, the clown. I liked him. Alright, are you ready? Ahh! I'm sorry. I'm sorry. I'm sorry. I'm sorry. I'm sorry. I'm sorry. I really hated when that happens. I'm sorry. The Pajarito Plateau was a wonderful out of this world place where you could wander in wonder no end

of the original beer or deer crossed your tracks. And it's curious how on this deserted plateau human voices still seem to vibrate somewhere. Among bird notes an occasional ripple of water and in the singing of the pines. Long before the invention of symbols on the development of an alphabet man recorded impressions of his visual world by means of pictures. Not always profound. It is nevertheless remarkable, appearing as it did long before art was taught in schools or written about in books. To find a common ground for the two professions of artist and archaeologist, I suppose we can say that one is interested in bones while the other is more interested in the skin of things. And I think he did have an amazing capacity for entering into the spirit of whatever he was working

with a tree in springtime or a child playing in the garden in one of his old prints. It was all such a personal warm acceptance of life and I believe the pack rat instinct that makes us carry off things of all sorts may eventually be our undoing. But then I have it too, so I'll be undone with the rest of the tourists. To me a piece of petrified wood is irresistible even now there are samples of colored sand in my storeroom from the red, the blue, the white, and the black forests in Arizona, colors that shimmered with rainbow iridescence until I thought I had discovered a new source of pigment. What I could not bring with them was the atmosphere that made their color.

Someday I'll take that sand back where it belongs. There is something precious about a clean, bass wood planned properly seasoned. The gouge sharpened to a hair's edge, sinks in and comes out of the wood at just the right time. How long does it take to make a wood cut? It's not often that the state of mind, the sharpness of tools, and unusual interest in a problem, combined to create a mood whereby the tool needs little guidance. Before the orderly process of printing is possible, the blocks are in a state of apparent confusion that tests mind, eye, and hand. Since each print involves about five blocks, you can extend your dexterity still further by starting several sets at once. Having learned to conserve my wits,

I begin with a sketch as a guide, not to be followed too closely. The charm of a color wood cut is usually a byproduct of good craftsmanship and does not become apparent until the print is thoroughly dried when all the colors are amalgamated and set. Occasionally, a visitor with the impression that making of prints is a simple matter. In fact, much easier than painting expresses it blandly. What does since you have? You cut the wood, print so many impressions and sell them. Another is, now tell me which of your prints do you like the best. Since at times I don't like any of them, there is nothing to do but a journey to La Fonda where a prosaic doctor, undertaker and realtor helped to change the subject. When Gus Balman came to New Mexico,

he was already a master of color woodcuts, an extremely difficult way to make a work of art because you have to get the register just right. The printing is a very difficult task and working with the wood, he could do anything with wood. I think the very difficulty of it was made it able for him to give his truly personal outlook, version, vision of what he was seeing. Every town of Spanish origin in the course of the year breaks routine activity with a few days of relaxation that could have make up a fiesta. Some years ago the artist and writers with pent-up desires to break routine with a real bust decided this might be the time to do something about it. But bonfires are old stuff. So why not a figure? Call him Old Man Gloom and let him burn up and from then on let joy be unconfined.

I did have time to do a head for him out of a corrugated board box which was jammed on a pole, a break with cheesecloth and stuffed to the shoulders with tumbleweeds. Not very convincing, but it did make a hot fire to jump through after the pole had collapsed. He loved puns and so did mother. And he also liked to make up songs. Somebody was coming to town and he make up a song about them. We called them bathroom ballots because he usually made them up while he was shaving in the bathroom. And he made a house for me in the backyard. And for a while I could fit in it, but it wasn't too long before I couldn't fit in it. So it sort of became a dollhouse. But it had little curtains

and it had a little mammalian floor. Although I wasn't aware of it as a child, I would say they certainly were devoted to each other. With all the wide expanse of her risen to observe them in, rains here take on a new meaning. A steady, gentle downpour of benefit to the land may turn into cloudbursts carrying fertile fields into raging royals. Without a tall, spired man-made structure to bridge the void between the scene and the unseen, the Indian dances and prayerfully asks a blue-black downpour of rain to come out of the mountains

spread over his fields. That the rain might have come anyway is beside the point, something happened that makes for a balance between sky, earth, and man. I often wonder where the artist would be, but for the prodding encouragement of a few optimistic souls who not only believe in him, but in all humanity as well. I often wonder where the artist would be, but for the prodding encouragement of a few optimistic souls and prayerfully asks a blue-black downpour of rain to come out of the mountains. Gasparman was an artist in his work and in his life. The generosity of spirit

that both Jane and Gas showed were probably the greatest gifts that certainly to me. I think he was showing an appreciation for life and, of course, his art was really just expressing what he wanted to tell the world and the only way he could tell the world about himself was through his art. What would be his greatest gift to me? I guess his greatest gift was the fact that he had a mother had me. And I'm just very proud of it. Because I've inherited from my mother a tendency to weep at certain times. I'm just very proud of my mother

and I'm just very proud of my mother. Da, where do Hornito sleep? Under this couch? No, I don't see any. It got horned rim pajamas. Has it got ants in its pants? No, I don't see any Hornito at all. But I saw one this morning in the yard and it didn't have a thing on but horns. Oh, Anne, that won't do. Tell your mother she must sew something for Toady right away. And now I've got to go to the studio. Da, why do you go out to the studio? There are a lot of patients out there whose joints won't work. Backstrings are twisted and one of them is lost his head. When you lose your head, can I look inside?

Sure, you'll see many things, but never mind. Oh Anne, saved again. And now I can go. Anne, ask your mother if we can have popovers tonight. This Dolores program is available on home video cassette for 1995 plus shipping and handling. To order, call 1-800-328-5663.

- Series

- ¡Colores!

- Episode Number

- 1103

- Episode

- Gustave Baumann

- Producing Organization

- KNME-TV (Television station : Albuquerque, N.M.)

- Contributing Organization

- New Mexico PBS (Albuquerque, New Mexico)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip-191-05fbg7xb

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip-191-05fbg7xb).

- Description

- Episode Description

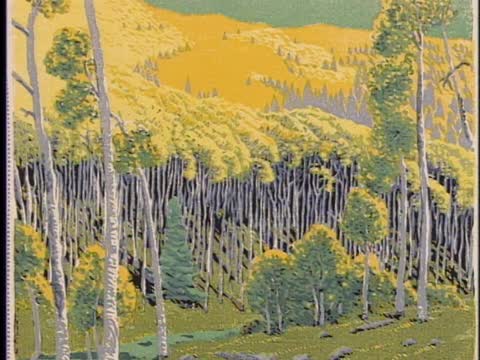

- One of America’s great craftsman, Gustave Baumann’s color woodblock prints are masterpieces of meticulous craftsmanship and artistic vision. Occasionally interrupted by those pesty puppets, the narrative for this documentary is composed of excerpts from Baumann’s own unpublished autobiography. This ¡Colores! presents an unparalleled insight into Baumann’s artistic mind and creative process and presents superb photographic tour of his beautiful woodblock prints. He used hand ground pigments, exact carving and fine papers to create flawless prints. Each print is a simple and elegant study of the customs, people and landscape of New Mexico. NETA Best Documentary winner. Funded in Part by New Mexico Arts.

- Broadcast Date

- 2000-05-03

- Asset type

- Episode

- Genres

- Talk Show

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:29:00.039

- Credits

-

-

Producer: Gaillard, Cindy

Producing Organization: KNME-TV (Television station : Albuquerque, N.M.)

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

KNME

Identifier: cpb-aacip-612616487a4 (Filename)

Format: XDCAM

Generation: Master

Duration: 00:26:57

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “¡Colores!; 1103; Gustave Baumann,” 2000-05-03, New Mexico PBS, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed November 5, 2025, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-191-05fbg7xb.

- MLA: “¡Colores!; 1103; Gustave Baumann.” 2000-05-03. New Mexico PBS, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. November 5, 2025. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-191-05fbg7xb>.

- APA: ¡Colores!; 1103; Gustave Baumann. Boston, MA: New Mexico PBS, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-191-05fbg7xb