Bill Moyers Journal; 108; The Americans

- Transcript

#108

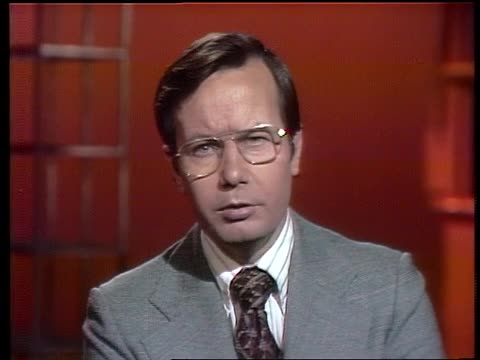

"BILL MOYERS' JOURNAL"

'THE AMERICANS"

January 2, 1973

MOYERS:

The politicians made so much noise last year that it was hard to hear anyone else. But there were other people who had other things to say than what you read in the paper.

I'm Bill Moyers, and in the next half hour we're going to hear some personal opinions about the issues of 1972.

With one exception the people you will meet are not house- hold names. They don't make the news; they live with it.

And

1972 was a big year for politics, sports and war. Sometimes it was hard to tell them apart. Politics and sports can be as violent as war, as Arthur Breymer and the Olympics reminded us. Sports has joined war as a political distraction from our problems at home. The big difference is that politics and sports reached conclusions in 1972. We know who won the Super Bowl, the World Series and the Election. But the war went nowhere and everyone lost.

Our show tonight is a look back at some of those headline stories, a sort of year-end look at the news through the eyes of people whose opinions rarely show up except as percentages in a Gallup Poll.

I collected these vignettes while doing other shows in this series in a variety of locations around the country. Here are some frank comments on politics, for example, from an inmate in a New York jail, a Spanish speaking furniture salesman in Los Angeles and a football player:

CONVICT:

We definitely relate to what's going on. We relate to the political campaign. It was such a farce, especially with this Watergate thing. Everybody was interested in that and everybody had the same opinion what if it was us?

MOYERS:

Was there some reason that you in prison felt particularly pertinent to the Watergate Affair? Did they do a good job of it?

CONVICT:

Yes. They did a blundering job of it. They blundered the whole thing. I mean, for professional men which they were supposed to be they shouldn't have got caught. It should have been a raffle-type episode. But they all got caught.

MOYERS:

What did the guys in prison say about it?

CONVICT:

They all had the same opinion: if we had done that, we would wind up with 15 or 20 years. But yet, due to the fact of their political background and political connections, they're not going to wind up with very much if they wind up with anything at all. But it was pretty well hushed up.

MOYERS:

Are you a cynic?

CONVICT:

I don't think I'm a cynic. I don't think so at all. be a little embittered at the politicians out there. I may

I don't believe that the country is standing together as a unit. If it was, the Vietnam thing would never have gone on as long as it has gone on. I could say that tomorrow that if this place was to go out, you would have everybody standing together to go out on strike... I mean, if it was for a very worthwhile purpose ... not a violent strike, just a strike to stop it. But if you were to ask them to all go out and go to work for their country, I don't think you'd get 10 guys.

Now this would give me an inkling of what's going on outside although I'm aware from reading the papers and watching television.

MOYERS:

Convict or citizen which do you think of yourself as?

CONVICT:

I always think of myself as a citizen. Convict, second class. I may be a second class citizen, but I always think of myself as a citizen. I mean, I've always been for America regardless of what I've done. A person can do things and believe me, as I've mentioned before with the Watergate thing, that was sanctioned by some pretty damned big citizens in the United States.

SPANISH AMERICAN:

Who in the hell can you trust anymore today? Yeah. Even our own President is hiring all these people to espionage or something that for me has no meaning. But when you stoop that dog-gone low to get these big and intelligent people from the F.B.I. and the C.I.A. and all these people from the White House to espionage on these people. And they don't even know if they're going to win or not, then they come out and say, "Well, I don't know a dog-gone thing about who hired me.'

And I feel that Nixon is a hell of a good guy, but at the same time, when these deals approach, you don't know who to believe.

MOYERS:

President Nixon, Joe, sometimes appears to fancy himself as a vicarious quarter-back on the Baltimore Colts, and maybe the New York Jets, and the Washington RedSkins. Do you ever fancy yourself as a vicarious President?

JOE NAMATH:

Yeah, I thought about what it would be, what kind of problems it actually is... what responsibility what little I could relate to it. You see, I don't actually know. How do I know how much is on his mind? He's talking about a world problem and a country problem. We have problems with a 40-man football team that sometimes seem colossal to us.

MOYERS:

You've never come out publicly for a candidate. Why is that?

NAMATH:

Well, whenever I see these people getting sometimes violent and very upset over political issues, I don't want to be involved in that. I don't want to alienate myself to anybody on any terms when it comes to politics. Like I say, I'm a believer in our Government and I'll vote for who I think is best, but I don't want to get involved in the sense where people are going to be rapping at me and feeling that I am this kind of person because I endorse this candidate ... a candidate.

MOYERS:

There's a lot of contrast now between football as a number one sport in the country with this emphasis on contact violence. They claim that all those people who sit up in this stadium and watch you on television are sort of armchair voyeurs who get a kind of pleasure out of the violence they don't have the courage to participate in themselves.

Do you think that's so?

NAMATH:

Yeah I know it's so in some cases. I don't know if it has to do with courage, but I've seen people who are relatively meek and quiet get in the stadium or in a ballpark and just let it go, man.

When somebody goofs up, they call him every name in the book and talk about his family and everything else. I don't think they'd say that to him face-to-face, but still, when they pay their admission, they sit up in the stands, they feel they have a right to do that. And maybe that carries over into politics too. The public feels that they have the right to say what they have on their minds. And sometimes even though they are not right, they are going to say it.

MOYERS:

Do you think there's been any kind of relationship between that attitude and the attitude of people who watch on television the scenes of fighting and destruction in Vietnam and simply don't react to it?

NAMATH:

War is war and there's nothing good about war except it's ending I don't of anyone that really enjoys seeing films of war and crime and people getting killed. I don't even watch them.

I tell you, when they come on, I try not to watch them. I don't really pay a lot of attention to what I see in the news anymore or what I read in the newspaper. I look at it and I consider it, but I don't take it for fact.

MOYERS:

What about the politicians?

Do you feel any sense of cynicism

or disbelief?

towards them as you do toward the medium

— —

NAMATH:

They've been rapped

I have a lot of respect for politicians. over the years, you know, bad politicians, liars, thieves and fortunately, we've had some good ones and I hope we continue to have some good ones. There's good and bad in everything and all we can do is hope that the good is better than the other.

MOYERS:

What if the President called you and suggested as he did to Don Shulla one year, that a certain play might work next Sunday?

NAMATH:

We'd consider it. We're always open for suggestions.

MOYERS:

That sounds awfully diplomatic.

NAMATH:

And if it's a good play, we'll sure use it.

You catch pretty good.

You want to try a long one?

I misjudged your speed, you're a little slower than I thought.

MOYERS:

Poor Joe had trouble all year with his receivers.

Off the gridiron the serious, more intractable struggles with America went on. 1972 saw women keep chopping away with the conventional wisdom that their role should essentially be subservient.

Women who would never think of overturning society were talking more and more about at least changing it, especially the structures of habit and prejudice by which men had come to take for granted their power to define the woman's station.

The barricades of male chauvinism had been assaulted and occasionally routed by the movement's jealots. But now real change in the common web of daily relations was up to legions of unpublicized women. Women who want to win recognition as human beings without giving up their roles as wives and mothers. This young woman is both a housewife and a wage earner in New Jersey:

WOMAN: I suppose in any kind of movement you have to have a radical

fringe that screams and hollers over everything, you know, the ladies who burn their bras and that kind of thing. But I don't think everybody who wants to see the changes has to be the radical fringe. You can be that big mass of solid work that's kind of coming on along behind it or something. I sort of see myself more there than burning my underwear or something like that.

MOYERS:

Do you get bugged by being judged daily on the stereotypes that exist about women today?

WOMAN:

Sometimes I do. I never get really irritated. If you're the woman in the group and there's always more women, you make the coffee and get the donuts for the guests. And I had no objection to doing that. But every now and then I think it would never occur to one of the men to do that. It's just that you're a woman, so therefore, you will do this little domestic thing.

In a job situation I'm not any more qualified to make coffee, in fact I make lousy coffee, you know. But I'm a woman, so I should make the coffee.

It's not a vicious, terrible, male chauvinist plot. It's just a minor irritation, but it all fits in with the whole stereotyped idea that you're the domestic one and you're the servant one and you-look-after-me sort of thing. And if you say something to a man, they don't even think about it. They don't mean anything by it, but they still expect you to make the coffee even after you argue about it.

MOYERS:

But if you don't get mad about these prejudices, these assumptions, by which you are bound, will they ever change?

WOMAN:

Well, I think women really are mad about them.

I just think that the violence of your reaction should be suited to the violence of the prejudice against you. I'm not going to raise a screaming roar over making coffee, but if it were a matter of a promotion or a job that I was qualified for and I wasn't going to get because I was a woman, then you would hear a lot more noise on the subject. But as far as the coffee goes, you know, just forget to make it every now and then. They can take a turn at it or something like that.

I just think there are so many important issues to get excited about than to scream and holler over every little thing.

MOYERS:

There was a lot of rhetoric in 1972 about the good life. The economy turned around and the gross national product started climbing again. But inflation hung on. The cost of food went up so much that people who could afford two pots could only afford one chicken.

For all the statistics on middle class affluence, for all the opulence of the very rich, one-third of the country lives in poverty and one-half lives only on the margin of modest comfort. The praise-makers kept reminding us through the political campaign that most of the country is unpoor and unblack which consoles just about everyone but the poor and the black. As the old year ended the racial minorities were still living with America's unkept promises.

I talked with a black woman in Georgia, a Hopi Indian in New Mexico and a farmer in Southern California:

BLACK WOMAN:

I really do think that we are one nation. I think most of the white citizens look at us through the same eyes that their forefathers looked at us when we got off the ship from Africa. I think they look at us in that light now. We are good for washing their dishes, scrubbing their floors, nursing their kids and that's about all.

MOYERS:

Thomas, what really makes you really mad at America right now?

HOPI INDIAN:

The fact that they are destroying some of our spiritual centers, the natural beauty of our country.

MOYERS:

Who's doing it?

HOPI INDIAN:

The American Government under the Bureau of Indian Affairs, who have set up the council people and they more or less dominate them and they do not quite understand legal terms and they start signing things away. To them it is holding up progress, but to us it is a preservation of natural beauty and the natural way of life and the spiritual and ancient knowledge that we have for the future is still intact there.

MOYERS:

Are you a farmer?

CHICANO FARMER:

No. I used to was. I used to work for 10 years in New Mexico for $45 a month.

MOYERS:

$45 a month?

CHICANO FARMER:

That's what I did before and then after Hoover, the wages went down. And I was working here for 10¢ an hour in 1929 and 1930. Now the money's still better, but everything is going up, groceries, clothes, everything. And it's pretty hard for our people, now for me, but the young generation. Most of the people would like to have a union, but some guys try to break the union.

MOYERS:

Don't you get tired of standing out here?

CHICANO FARMER:

Yeah, awful tired. Real tired. Night time I can't sleep because I am awful tired. It's pretty hard to be standing here all day.

MOYERS:

1972 was the year in which the White House cried, 'Peace, peace', but there was no peace. As the war lingered on, I kept encountering people whose lives it had marked forever, people for whom the war will never end. I think the cruel paradox of the war's effect on the country is clearest in separate conversations I recently had with two fathers. One is the Reverend Raymond Pontier, Congregational minister in Clifton, New Jersey. His son, Glenn, is in the Federal Prison in Danbury, Conn., for refusing to be inducted. Glenn Pontier recently joined the other prisoners in a prolonged fast as yet another protest against the war.

The second man is James Davis, a retired druggist who lives in Livingston, Tennessee, not far from Oak Ridge. His son, Tom, died in Vietnam on December 22, 1961 -- the first American boy to be killed in combat with the Viet Cong. I talked first with Reverend Pontier:

REVEREND JAMES PONTIER:

In terms of my wife and my own personal feelings we've always respected Glenn's personal integrity. He did not do this for kicks, he did not do this because he was turned off; he did this because he believed it would be the honest thing to do.

But our reaction was: Glenn, do alternate service. Take care of your alternate service and then go out and do some kind of job that you really want to do. But as Glenn was arrested and as we began to go with Glenn through the trial, I think we began to see that here is a guy who just wasn't talking about the issues and concern and the cause of peace. Here is a guy who felt that he had to do it and the witness that he made ... I think he would have made a witness outside of jail. But the kind of an impression that he has made, say within our denomination and within our local parish here or among his friends, has been simply tremendous.

People ask: What good does the past do? What good does it do to go to jail? What good does it do to do good? And when I've talked to Glenn about it, he says, "You know, that's the wrong question, dad." He said, "It's not what good it will do, although you hope it will do good, it's what good should I be doing.'

JAMES DAVIS:

They closed the town down the day of Tom's funeral.

MOYERS:

Just closed it down?

JAMES DAVIS:

Just closed it down.

They put all the flags out and had a Tom Davis day, dedicated a football stadium to him. awful nice to us in the family, the county has.

They've been

MOYERS:

Did people know about Vietnam then, know where it was?

JAMES DAVIS:

I've been quoted as saying: Well, I didn't know where

No. I didn't know where it was. "Where in the hell is Vietnam?" Vietnam was. I knew where Indo-China was but I didn't know anything about this.

MOYERS:

What did you think when you heard he'd gone there?

DAVIS:

Well, after I'd read a little about Vietnam, South Vietnam, North Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, how it had been split up and everything, I thought I guess they've had it.

I imagine the recruiter talked him into it.

MOYERS:

Did he come home and talk to you?

DAVIS:

Oh yeah. He asked me what I thought about it. I said I didn't believe the recruiter. So he brought the Sergeant up. And he was telling me what a good deal he got. He did; he got a good deal. And they did do what they said they'd do to him, but he was in a special branch of the service, you know, Special Forces.

MOYERS:

Do you think that the way things have come out, the way the war has been dragging on has in some manner diminished the importance of Tom's contribution.

DAVIS:

No. No, I think every man owes a duty to his country I'm one of those fellows I'm for my country right or wrong. guess I am. We're in the minority, but I don't know

PONTIER:

I'm angry that American boys, 2,000 or so American boys were

killed. I'm very angry at that. I think Glenn and others, I don't exclude so many others that have suffered, the guys who have gone to Canada, because they have been alienated by the monstrosity which is taking place in Indo-China, so yeah, I'm angry in that sense. I'm angry and discouraged because it has been necessary for the guys to stand up for what he believes in as a Christian, as a moral person, as an ethical person... but to stand up for these ideals and to say that because he really believes this way, that he has to spend a year in prison.

MOYERS:

35% If you really take literally what comfortably our country has

been espousing, you will pay a price for it.

PONTIER:

You will pay a price for it because our kind of a society has set the ground rules and our kind of a society says you are permitted to do this and this within the bounds of what society sets up as its own laws or rules or mores of decency. And beyond that you are going to be ostracized and penalized and you'll be hurt in some way.

MOYERS:

Is there any redemption in what your son is doing except his own? Has society made any difference? The war goes on, the bombing has continued 8 years later. For all the passion

For all the passion and commitment of Glenn what's changed?

PONTIER:

And you can say the same thing of almost anyone else on the horizon, I think, of history today or yesterday except the person who's in a position of great power, economic power, but I think and I believe historically that the record would show that the real change in history has come because people have dared to stand up for their convictions as part of the minority.

MOYERS:

How did you get the word that he had been killed?

JAMES DAVIS: Telegram. Telegram ... cab driver brought me a telegram.

MOYERS:

A cab driver?

JAMES DAVIS:

Eh-huh. We don't have a Western Union here.

MOYERS:

This is the telegram?

DAVIS:

That's right.

MOYERS:

No phone call?

DAVIS:

No.

Not then, no.

MOYERS:

Twenty some odd years of a boy's life wrapped up in a telegram.

DAVIS:

Yeah. And you know what it is when you go to the door and there stands a man and he knew what it was too, see. He was as tore up about it as I was. Pretty rough when your wife's in the kitchen and you're at the front door and a man hands you a telegram and you know what's in the telegram before you open it because in the service no news is good news. You don't get telegrams hardly ever. And his wife's up at her mother's and you've got to tell all these people about it. Pretty tough. That's the toughest part of doing

it.

MOYERS:

And the letter from President Kennedy ? I think I saw it over here.

DAVIS:

Yes. He writes about like I do. "...I share your pride in your son who gave his life defending his country, but freedom and democracy for all mankind ..

Well, anytime I think, you're shooting a Communist you're defending the freedom of your country. Maybe that's because I don't like Communists.

MOYERS:

And you felt your son gave his life in that cause?

DAVIS:

eah. You're told your duty when you sign. You do what you're told. Or I did and most soldiers did up until now, I think. don't know. I think it's changing.

MOYERS:

Your faith ...during these years your faith hasn't wavered?

DAVIS:

No. I haven't got a boy that's wavered. No member of my family, even my daughter ...when this thing happened, she was going to join the Marine Corps, you know what they call them?,

or something.

What do they call them?

...

WRENS

MOYERS:

I don't know.

DAVIS:

Yeah,

Well, it's a branch of the Women's Corps of the Marines. she wanted we had an old retired Sergeant Major in the Marine Corps that was Sheriff at the time and she talked to him about it. Oh yeah. "I want to get into the Marine Corps.

MOYERS:

Why is this? Is there something peculiar to Livingston? Something peculiar to your family? part of the country? Something peculiar to this

DAVIS:

No, I don't think so. My kids' patriotism. they've just all been taught

I guess some of me rubbed off on them maybe.

MOYERS:

What kind of a boy was he?

DAVIS:

I'd call him just a typical, everyday, American boy. He liked to hunt and fish and roam around in the woods. He didn't want a lot. But my son was just one of the 50,000 that got killed. in Vietnam. They all did their duty; they did their duty just like he did... and like people did in World War I and World War II and the Spanish American War, Civil War. We owe those fellows something.

MOYERS: What?

DAVIS:

Well, in the first place we owe them this country. If it wasn't for those fellows, we wouldn't have a country, would we? You and I wouldn't be sitting here, maybe. At least we wouldn't be saying what we think, maybe.

I like this country. I say what I cotton-picking please about who I please and if the shoe fits, wear it.

MOYERS:

And you don't think it was in vain?

DAVIS:

No, I don't think so.

MOYERS:

Does the way it comes out have something important to say to you about the value of his death?

DAVIS:

No.

MOYERS:

James Davis' son, Tom, went to Vietnam 11 years ago with a Civilian Passport, our Government trying even then not to admit that a war was going on there. Things come full cycle and 11 years later through secrecy and evasion, yet another administration, the third in succession, is trying to play down the bloody, awful truth about what's being done there in our name.

Long after the war has lost it's meaning to most people, we keep blasting away not only at the armies of the North, but at it's people as well, killing civilians and tearing up a country to put pressure on a handful of leaders.

Our own country is still divided, divided between the Davises, who believe that duty is saying is saying 'yes', and the Pontiers, whose conscience tells them to say 'no'. The majority of people just want to put it all out of sight.--

Let the fathers mourn. Let the protesters rot. Let the bombers bomb. Just don't bother us with it anymore.

Well, here we are in a New Year. And the war lingers As long as it does, there'll be another Tom Davis and another and still other men will go to jail. Which kids will be next? These two we filmed recently on the Pacific Coast or two Vietnamese youngsters, whose names we'll never know? Never mind that they are just children. This war will wait.

I'm Bill Moyers. Good night.

- Series

- Bill Moyers Journal

- Episode Number

- 108

- Episode

- The Americans

- Contributing Organization

- Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group (New York, New York)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip-15532842edc

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip-15532842edc).

- Description

- Episode Description

- Bill Moyers interviews Americans around the country about the nation’s present and future. Moyers talks with the father of the first GI killed in Vietnam; the fathers of a conscientious objector. And football’s famed Joe Namath.

- Series Description

- BILL MOYERS JOURNAL, a weekly current affairs program that covers a diverse range of topic including economics, history, literature, religion, philosophy, science, and politics.

- Broadcast Date

- 1973-01-02

- Asset type

- Episode

- Genres

- Talk Show

- Rights

- Copyright Holder: WNET

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:30:49;16

- Credits

-

-

: McCarthy, Betsy

Director: Sameth, Jack

Editor: Moyers, Bill

Executive Producer: Prowitt, David

Producer: Toobin, Jerome

Production Manager: Case, Lyle

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group

Identifier: cpb-aacip-da86651d927 (Filename)

Format: LTO-5

-

Public Affairs Television

Identifier: cpb-aacip-5b4d3d1f279 (Filename)

Format: U-matic

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “Bill Moyers Journal; 108; The Americans,” 1973-01-02, Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed January 6, 2026, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15532842edc.

- MLA: “Bill Moyers Journal; 108; The Americans.” 1973-01-02. Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. January 6, 2026. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15532842edc>.

- APA: Bill Moyers Journal; 108; The Americans. Boston, MA: Public Affairs Television & Doctoroff Media Group, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15532842edc

- Supplemental Materials