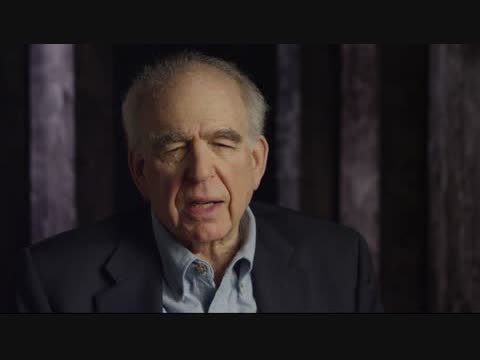

American Experience; 1964; Interview with Jon Margolis, Author, The Last Innocent Year: America in 1964, part 3 of 5

- Series

- American Experience

- Episode

- 1964

- Raw Footage

- Interview with Jon Margolis, Author, The Last Innocent Year: America in 1964, part 3 of 5

- Contributing Organization

- WGBH (Boston, Massachusetts)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip-15-n29p26r48z

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip-15-n29p26r48z).

- Description

- Description

- It was the year of the Beatles and the Civil Rights Act; of the Gulf of Tonkin and Barry Goldwater's presidential campaign; the year that cities across the country erupted in violence and Americans tried to make sense of the Kennedy assassination. Based on The Last Innocent Year: America in 1964 by award-winning journalist Jon Margolis, this film follows some of the most prominent figures of the time -- Lyndon B. Johnson, Martin Luther King, Jr., Barry Goldwater, Betty Friedan -- and brings out from the shadows the actions of ordinary Americans whose frustrations, ambitions and anxieties began to turn the country onto a new and different course.

- Subjects

- American history, African Americans, civil rights, politics, Vietnam War, 1960s, counterculture

- Rights

- (c) 2014-2017 WGBH Educational Foundation

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:57:59

- Credits

-

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

WGBH

Identifier: cpb-aacip-6c2b71fae7a (Filename)

Duration: 0:57:59

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “American Experience; 1964; Interview with Jon Margolis, Author, The Last Innocent Year: America in 1964, part 3 of 5 ,” WGBH, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed December 16, 2025, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15-n29p26r48z.

- MLA: “American Experience; 1964; Interview with Jon Margolis, Author, The Last Innocent Year: America in 1964, part 3 of 5 .” WGBH, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. December 16, 2025. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15-n29p26r48z>.

- APA: American Experience; 1964; Interview with Jon Margolis, Author, The Last Innocent Year: America in 1964, part 3 of 5 . Boston, MA: WGBH, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15-n29p26r48z