Our Centennial State; Episodes 1-4

- Transcript

[background music] [Start of Part 1, EARLY TRAIL, of Our Centennial State] [John Rugg, narrator and host] The flat table land rises some 2000 feet above the floor of the valley. The Spanish named it well, Mesa Verde, the green table. Here in the walls of the mesa are hundreds of abandoned cliff dwellings well-preserved evidence of a very old Indian culture. The Anasazi, meaning ancient ones, occupied the southwestern part of Colorado for almost thirteen hundred years. These were the descendants of even earlier tribes that over centuries of time had slowly migrated from Asia into North and South America. These first inhabitants of our centennial state became farmers, planting corn, beans and squash up on top of the mesa while living in well-protected cliffs dwellings under the large overhanging rocks.

By the end of the 13th century they had vanished from the region following trails that took them south into the Rio Grande Valley. Here they built and lived in adobe villages. For these were the ancestors of the Pueblo Indians of the Southwest. [female touring Mesa Verde] Why did the Indians leave here? [Tour Guide] Well, we're not really sure why the Anasazi left here. We do know there was a long drought towards the end of the twelve hundreds which probably brought on starvation here and maybe forced the people out and they probably moved further south into areas that were more productive. [Narrator] Whatever the reasons for leaving these settlements, The cliff dwellings would never be used again. In fact, they would never be rediscovered for almost 500 years. At the very time that our Declaration of Independence was being made known to the world, two Spanish priests and their party of eight men were camped here in the very shadow of Mesa Verde.

It seems incredible that in our country's history when English colonists along the Atlantic seaboard knew nothing about the vast wilderness out west. Men from Spain were here exploring the southwestern part of what was to become the centennial state. In 1776, Father Escalante and father Dominguez were searching through much of western Colorado and eastern Utah for a new and better route to the Spanish missions in California from their northern outpost of Santa Fe. These early trails of discovery had come not from the east but rather north from Spain's great empire in Central America and Mexico starting in 1539. [Actor 1 depicting Coronado] No longer is it enough to ride behind the leader or to send someone else in my place. I want my own home command. [actor 2] And you shall have it, Coronado. Sooner than you expect. At long last I have news from Spain. King Charles has long wished to know the truth of

Cabeza de Vaca allegations as to what he saw during those six years of trying to make his way back here to the Capitol from the north. [Actor 1] You refer of course to the legend of Cibola (?), those golden cities of Cibola that no one has been able to find. But what of your expedition north only last year headed by the Franciscan Marcos De Niza. [actor 2] You know as well as I that what De Niza brought back were more allegations, no sightings with no evidence due largely to the death of De Niza's friend, Esteban. [actor 1] The death of the black man at the hands of the Indians was most unfortunate. [actor 2] A tragedy. When you think how near De Niza must have been yet not daring to venture further for fear of a fate similar to that of Esteban. [actor 1] And now you want confirmation. The knowledge that such a place exists. [actor 2] That will be part of your task me Capitan General. You will lead the largest of all expeditions north with the authority and sole use

necessary to penetrate farther than we have ever probed. You will claim for the Spanish crown not only the land but the wealth that is sure to be found. It is a great opportunity, Coronado. [music interlude; narrator] In the spring of 1540 Coronado and his expedition started north from Compostela ??. For two long years he searched for the legendary Cibola traveling through much of our Southwest passing within a few miles of Colorado. Instead of gold, he found a dry desert-like environment populated only with terraced Indian villages that he and his men called pueblos. What Coronado and succeeding Spanish expeditions never realized was that they gave to this region far more than they ever took away from the land.

Hispanic culture introduced the Indians to Christianity. Missions were built as well as new towns with a new architecture. Spanish names like Sangre de Cristo, Rio Grande, Santa Fe were given to mountains and rivers and cities. The explorers brought the first cattle and sheep into this region and rode on the backs of these four legged creatures never before seen by Native Americans. The horse would change the Indians' way of life. By 1800, Native Americans on the great central plains of North America had adopted the use of the horse in a nomadic style of living that was much different from what they had been used to before. These Indian groups who had earlier farmed on the eastern fringes of the plains, now spent more and more time on horseback following herds of wild game. Tribes with names like The Crow, The Dakota,

the Sioux, the Cheyenne moved out of the woodland area around the Great Lakes giving up their former pottery making and the raising of corn to live and hunt on the Central Plains. By 1800, the Ute Tribe occupied much of western Colorado. The Cheyenne and Arapaho, its eastern plains. They acquired skill of riding horseback, the Indian soon learned as well the need for following the trail of the shaggy beast. So how best to divide the herd, to single out the cows or bulls to be killed. At one time on the Great Plains of America, it is estimated that there were millions of these animals roaming in great herds across the prairies. Small bands of perhaps 100 to 300 Indians that made up each tribe came to depend almost entirely upon these beasts for providing the necessities of life. [unidentified male] Buffalo which is more accurately called a

bison not only provided shelter for the Indians' new home, the tepee, but provided as well much of their food, their bedding, and of course warm robes. The bones of the bison were even used to scrape clean flesh from the hides. The tendons were stripped into thread to sew together the skins to make their garments. Even dried buffalo manure that today we call buffalo chips was put to use as a fuel. [narrator] Hunting became the central task of the Indian men. For women, it was cleaning and curing the hides and cooking the meat. As the bison moved to new grazing lands, so moved the Indians and their villages quickly and efficiently. Horses and hunting grounds became valuable. It is little wonder that the many tribes on the

plains became warlike to acquire or protect what they considered to be their land and property. War between tribes, in fact, became an accepted part of Indian life on the plains. Tolerated, as well, were the small numbers of white men who moved across the Indians sacred hunting grounds toward the mountainous lands beyond. Some searching for the yellow metal while others laid strange looking pieces of iron in streams to catch and kill the beaver. The year, 1832, the completion of Fort William, better known as Bent's Fort, named after the well-known trader and merchant William Bent. Here in the southeastern Colorado stands a replica of that famous early fort in western history. Now designated as a national historical site, Bent's Fort was the first semi-permanent American settlement in Colorado. It was in continuous use from 1833 to 1849.

More importantly, it was located on the northern or mountain branch of the Santa Fe Trail connecting St. Louis with the growing trade center of the New Mexico Territory. Here William Bent and his partners, brother Charles Bent and Ceran St. Vrain established a trading post for merchants and trappers. It also became a supply station for soldiers of the United States Army patrolling along the border between U.S. and Mexican territory. The Arkansas River over there was in fact the border at this point. The fort served mountain men as well supplying them with needed food and provisions as they trapped the streams and rivers of the Southern Rockies. For many years they had traded this kind of pelt, beaver, but by the middle 1830s the demand for such pelts was becoming less and less. The reason? Well, back in eastern cities hats made with beaver were gradually being replaced by the much newer and fancier silk hats. At the same time

however there was a growing market in St. Louis for this kind of hide, buffalo. In fact, a buffalo hide out here in the West could be traded from the Indians for about twenty five cents worth of knives, beads and trinkets and then transported back east and sold on Eastern markets for as much as $6. It was a very profitable transaction for the trader. It's little wonder that families passing through here on their way to Santa Fe were impressed by such trading. Even young people 13 years of age wrote back home about what they had experienced. [female child reading] Dear Laura, It has been 46 days since we left Missouri on our way to Santa Fe. The trail is long and wearisome. Last week the weather was very hot and dry. Thank goodness for my bonnet. It does help to keep the sun off my face. The only relief is when we cross

rivers but even then, it is often necessary for the men to help push the wagons through the muddy waters. A week ago, we were stopped by a small band of Indians. Luckily for us they wanted only a few items in trade, and then left us alone. Today we are resting at a trading post called Bent's Fort. We are getting ourselves cleaned up while the men are repairing damage to our wagons. There is much trading going on between the Indians and the owners of the Fort. This morning, General Kearny and his troops arrived. What a sight. I understand from father that they are on their way to Santa Fe to protect our country's interest in this part of the West. There is even talk of war with Mexico. [trumpet music] Following General Kearny's march into Santa Fe, war with Mexico had indeed become a reality. Within two years, American troops forced a settlement. What is now called our Southwest became United States territory in

1848. Later, to be divided up into states, by Congress when enough people would settle the land. For what was to become Colorado, settlers began arriving in the early 1850s. At first, they were largely Mexican farmers pushing northward from towns in the Santa Fe to the San Luis Valley. Here they settled and began to build towns with names like Garcia, San Luis, Conejos. And while villages became towns, the land started to bloom with crops planted after the introduction of irrigation systems. It was land that had seen the coming and the going of the Anasazi. Felt the influence of the Spaniard and the Mexicans. For years its mountains and plains had been occupied by nomadic Indians depending upon the horse and the bison. Up its river valleys came the trappers and American traders from the east. [End of Part 1, EARLY TRAIL, of Our Centennial State]

These early trails were fast becoming dirt roads for settlement. [Start number 02, Pike's Peak or Bust, Our Centennial State narrated by John Rugg] [Start number 02, Pike's Peak or Bust, Our Centennial State narrated by John Rugg] It's one of the best known mountains in our country. One that is seen first by travelers as they approached

the Rockies from the east. The majesty of the peak inspired Katherine Lee Bates to write the words for a song she entitled "America the Beautiful." This 14,110 foot mountain is known simply to you and me as Pike's Peak. It has long dominated the landscape here above the city of Colorado Springs. [music] The name given to the mountain dates back to 1806 when it was first discovered by an exploratory expedition headed by the young captain Zabulon Pike. At that time in history, he was mapping for President Jefferson part of the western region of the historic Louisiana territory. From that time forward, Pike's Peak has been an important landmark not only for the trailblazers and trappers but for the prospectors and settlers as well. Especially was this true in the late 1850s. With its location in the Rockies and at the western edge of Kansas territory made it the best known landmark available to

help identify the general location of newly found gold. Early in 1858, two Parties of gold seeking men, one from Georgia led by William Green Russell, the other from Cherokee Indian Territory organized by Captain John Beck, joined as one along the Arkansas River. and then proceeded along the front range of the Rockies, descending Cherry Creek to where it emptied into the South Platte River. For days, the party made up of over a hundred frontiersmen and Indians worked the streams and riverbeds without success. Finally in early July, after most of the original party had given up in disgust and started back home, the few remaining members uncovered small pockets of the precious metal not far from where the Cherry Creek and the South Platte River come together. The men quickly established a camp site, naming it after the Latin word auraria meaning gold mine or gold region.

The news of what was found here close to what is now downtown Denver spread quickly. A trader by the name of Cantrell visited the party here on July 31st. Five days later, when he left, he was seen carrying a sack of pay dirt heading for his home in Westport, Missouri, a town just east of the Kansas territory. Other traders and mountain men were quick to spread the word north of Fort Laramie and south to Santa Fe. Newspapers were soon printing stories and maps that had readers talking with anticipation. [actor, Tom] Marian, listen to what it says here in the paper about what's happening out there in that Pike's Peak region. Mr. John Cantrell an old citizen of Westport discovered three ounces of gold which he merely dug with a hatchet and washed out in his frying pan at a stream called Cherry Creek. Not far away, a French trapper named

Richard dug out several ounces of the precious metal with nothing more than his axe. [actor, Marian] Tom, that sounds too good to be true. I can't imagine gold could be that easy to find. [actor, Tom] Neither would I. Then again why would they print it here in a paper if it weren't fact? [Marian, actor] And how do you suppose they're getting out there? [John, actor] Well they've got three different routes . . . [fades away] [Rugg] The effects of the writings and stories told and retold concerning the newly discovered gold grew to exaggerated proportions. People everywhere seemed to be caught up in the excitement and possibilities of making quick fortunes out west. Trails across Kansas territory toward the Pike's Peak region were soon filled with gold seekers loaded up with provisions for the seven hundred mile, two week overland journey from the Missouri Valley region. By November, a party of would-be miners led by William Larimer had established themselves on land directly across Cherry Creek from the Auraria town company. These men

from eastern Kansas called their new settlement The Denver City Town Company named in honor of General James Denver, governor of the Kansas territory. Converging to the region as well where the yonder-siders prospectors who had gone west to California in the gold rush of 1848 found little or nothing and then gradually worked their way back east to the Pike's Peak region. Most of the early discoveries of gold along the front range of the Rockies were made by a technique of surface or placer mining known as panning. With this method, the prospector placed gravel and sand that he had dug into his pan, added water from the stream and then shook the pan vigorously, helping to make the heavier particles of gold settle to the bottom of the pan. It took an experienced miner only a few minutes to thoroughly work the mixture to gradually pour off the water, to pick out and discard the large rocks and pebbles.

And finally, if he were lucky, in the bottom of the pan would be the yellow gleamings that he was seeking. What most of the prospectors quickly learned was that it was necessary to repeat this slow process 80 to 100 times a day shoveling over a ton of gravel and sand just to separate perhaps a few cents worth of gold dust. [Actor 1] Where is all this gold they told us about about in them newspaper stories? I ain't seen none of it. [Actor 2] I've panned panned up and down this stream for a week. And all I've got to show for is less than 50 cents worth of that darn stuff. [Rugg, narrator] Disappointment and bitterness replaced earlier feelings of excitement and hope. Over half of the thousands of people who made the long journey out to this region gave up and returned to where they had come from. The Gold boom was rapidly becoming a gold bust and would have except for what happened here on May 6, 1859.

On that date, a man by the name of John Gregory discovered at this very site near what is now Central City the outcroppings of a rich load of gold ore. A load of gold ore is really a vein of gold. Part of it sometimes lying close to the earth's surface. It usually is contained in rock that bears a high percentage of quartz. Gregory's load discovery was one of the first of its kind in this whole region and the news of it set off a stampede into the mountains that was unbelievable. [Actor 3] They found gold? Where? Out west in the Rocky Mountains. Gold, they're finding it everywhere! [Rugg, narrator] Almost overnight some fifty thousand people rushed to the Rocky Mountains from towns and cities back east and from lands as far west as California. Plains were staked, tents were set up, trails and crude roads cut into the mountains. Mining camps sprang up everywhere. Many times miners found what looked like rich ore only to discover later that it

was worthless pyrite or what is called Fool's Gold. Of course, any gold discovered in ore must somehow be separated from the rock in which it is found. One of the methods often used was the rocker. A device that could be operated by just one person and hence a very quick and efficient way to prove out a source of gold ore. Used as well, was the sluice, a long slanting wooden trough usually operated by several men who shoveled in the pieces of ore. As the ore was washed by water, it slowly tumbled down the trough. The heavier gold particles that broke off would sink to the bottom of the sluice and be trapped next to thin cross boards called riffles. With these and other methods, out came the gold. Close to a quarter of a million dollars worth in those first few months alone. When the news of the discoveries at Central City

reached back East, people had more doubts than hope. Was this to be another false gold boom like a year earlier? Another Cherry Creek hoax? Newspapers sent very important men to see for themselves what was happening out west. One such gentleman, Mr. Horace Greeley of the New York Tribune, returned from the Gregory diggings with important news for the country. [actor portraying Greeley] ...for you gentlemen today. [actor, reporter 1] Mr. Greeley, tell us if you will, have you actually seen gold dug from the various mining sites out there? [actor portraying Greeley] Yes, gentlemen, I must admit that I've seen what one company took out of the ground at a cost to them of not more than twenty five dollars. It was a lump of ore estimated to be worth over five hundred dollars. [actor, reporter 2] Mr. Greeley, how many people do you estimate are at the dating site at this time? [actor portraying Greeley] Well, I would venture to guess that there are some five thousand men and women up in the ravine where I visited. Half of whom have been there for less than a week. Approximately five hundred new hopefuls arrive each day. [actor, reporter 2] Have they all found gold?

[actor portraying Greeley] No. No those five hundred new hopefuls are balanced by about a hundred who give up and leave each day. Most of those that go away are convinced that Rocky Mountain gold mining is one grand humbug. Some of them have prospected only two or three weeks but they've exhausted their provisions, worn out their boots and found nothing. [actor, reporter 1] What about the future of this gold rush and the region itself? Would you care to comment on that. [actor portraying Greeley] Well as you know, mining plays an important role in almost every useful industry. Two coal pits already at use in the digging sites, a blacksmith has set up his forge and is busy making a good thing out of sharping picks at fifty cents each. As towns and cities grow, so too will the economics and prosperity of this area of grow. Gentlemen, mining will affect the growth of this region perhaps more than any other industry. [narrator] Words of Horace Greeley not only brought credibility to what was discovered here in these Rocky Mountains

but encourage as well countless numbers of easterners to come West and seek a variety of opportunity in this region. Mr. Greeley also knew that as more and more people came West to dig their fortunes in these mountains and more and more land speculators, merchants and town promoters would follow close behind to try and make business fortunes. During 1859 alone, hundreds of supply wagons rolled westward to the Pikes Peak Region carrying not only food, clothing and mining tools, but large quantities of lumber, building materials, even printing presses. By the time Gregory had unearthed his rich discovery, 27 year old W. N. Byers had already published his first edition of The Rocky Mountain News, a daily publication that would keep the population informed of new discoveries and local events. In April of 1860,

the two early settlements of Auraria and Denver City Town Company had been brought together as one by William Larimer. The majority of people agreed to the permanent name of Denver City. Central City was changing as well. Gone were the tents and lean to's, the many mining camps that dotted this whole area during those first months. When W. N. Byers designated this particular location central to all the other mining settlements the name seemed to stick. Permanent buildings not only began to take shape but businesses were quick to establish themselves. This is the original house built for Billy Cousins, the first appointed sheriff of Gilpin County. Not far down this street was the home of the now famous Aunt Clara Brown, the first black person in this region. She not only operated a very successful laundry business but was the only nurse for miles around. She also did much to establish this Methodist Church that still stands today. To the south and

west, towns like Colorado City, Fairplay, Canyon City, Breckenridge and Oro City were developing fast Irrigated farming was now well established along branches of the Arkansas River. Claims clubs, people's courts, mining districts were all trying to give some direction to law and order. Pikes Peakers agreed on one thing - it was time for a territorial government. On February 28, 1861, in Washington D.C., Congress finally gave in to the pressures of westward expansion and established territorial governments for Dakota, Nevada and Colorado. The territory of Colorado, created from four others, was at last a reality. It had been an eventful three years starting in 1858. By 1861, however, the excitement of finding nuggets and quartz gold was giving way to ideas of permanent settlements, government and growth.

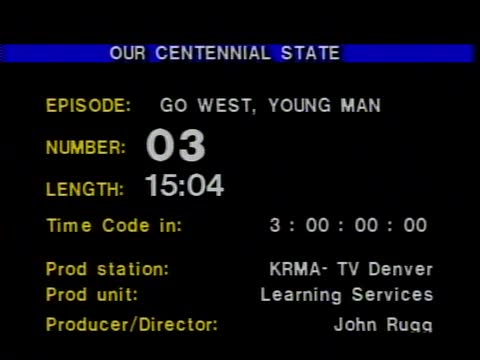

For there were many who believed that the future of this new territory called Colorado lay not in gold, but rather in farming and industry, scenery and climate. They would be heard from in the years ahead. [Music ending Part 02 of Our Centennail State] [Beginning of Part 03 of Our Centennial State: Go West, Young Man] [Narrator] It was known as the Homestead Act passed by the Congress in the year 1862.

It was a well-intended effort to encourage families to move west and settle vast areas of undeveloped public land. Such westward migration was also stimulated by the government giving railroad companies large tracts of this wilderness area in proportion to the amount of new rail lines they built westward. Such land, often in better locations, was then advertised for sale by the railroad companies at low prices to allure settlers west. Such ads were even widely circulated in Europe. [actor] Look, sir. Take this opportunity for us in America. [narrator] Over the years, hundreds of thousands of families, including great numbers of newly arrived immigrants, took advantage of such land offers moving out onto the territorial Great Plains including eastern Colorado. [actor, Henry] It's ours. Agnes. In five years will have clear title to it. [actor, Agnes] But, Henry,

the prairie is so so empty, so full of nothing. There are no rivers or streams close by. There are no other farms. There aren't even any trees. What are we going to build a home with? [Narrator] Most of these early homesteaders use the only thing nature had left them, sod. The top four or five inches of soil that was held together firmly by the roots of prairie grasses. When lifted and cut into large rectangular blocks, sod became an amazing building material. This old soddie has lasted over a century. There were hundreds of these soddies built here on the prairie lands in eastern Colorado. Placed layer upon layer, the sod made a remarkable thick and sturdy wall helping to keep out the winter cold as well as the summer heat. When he could afford it, the homesteader often called a "Sod Buster" used his freighter wagon to haul lumber

and heavy building materials from the nearest rail center to improve his home. Inside the walls of the soddie were usually whitewashed with a mixture of lime and water to prevent the sod from crumbling so fast. There were perhaps a few items of furniture that had been brought with the family from back East, including the old stove. One very important fixture. It really served two purposes: cooking the food as well as heating the house. The fuel? Well, at first it was simply dried buffalo or cow manure called chips. Mother and father slept back here. The children, up in the loft. Bed time came early especially on school nights. The school you say, oh yeah, it's over 100 years ago homesteaders were quick to see to the educating of their children. Only out here on the prairie, school was different since it had only one room. [sounds of children playing] I bet ya. You're always crowding in. You're gonna get it. You don't scare me none, Jimmy Wilson

[sound of water being poured] [actor portraying a teacher] All right, children, let's quiet down. And, you have some catching up to do. I'd like to see you after school for your make-up work. [child actor] Yes, m'am. [teacher] Jimmy, you're late again. [boy actor] But, Miss Bishop . . . [teacher] I don't to hear any more excuses. You'll see me after school. Mary I want you to help Melissa with her reading this afternoon. Henry, I want you to help Tom and Carl with their capital letters. Let them start with their names first. The rest of you, get out your slate boards. We are going to start with sums this morning. I want you to copy the problem and then write the answer. What page have you been reading on, Melissa? [child answers] I think it was this one [child reads aloud] [young boy actor] I can't get the hang of capitals. [boy actor reply] It's just like making a figure eight

that's fallen over to the right. [Teacher] All right, that's better. [Narrator] The one room schoolhouse was an important part in the lives of many early Colorado homesteaders living here on the plains. So, too, was this invention. The self regulating windmill. Automatically adjusting itself to wind pressure pumping underground water upward into large holding tanks. For the homesteader it meant that he would no longer have to haul water from faraway streams and rivers to supply his family needs and any livestock he owned. His crops however would still have to rely upon what nature could provide. In this semi-arid country, an average of only 15 inches of moisture each year. It's no wonder that some people took matters into their own hands. Greeley, Colorado, one of the largest communities in the northeast part of our state named after the well-known publisher of The New York Tribune, Horace Greeley. The growth of the city and its surrounding farmland can be traced directly to a series of

ditches and irrigation canals that diverted river water for the development of this early farming community. [actor singing song about farmers] [Narrator] Greeley was unique from another standpoint, it was organized back in New York City in 1869 as a planned farming settlement. To this man, Nathan Meeker, agricultural editor of The Tribune and president of the new colony, goes much of the credit for its early success. After serving several sites for the new settlement, a location was agreed upon close to the Cache la Poudre River. And directly on the newly built Denver-to-Cheyenne rail line. By May of 1870, the first of the Union colonists began to arrive in their new settlement. Quickly, the streets were surveyed and laid out. Trees were planted. A school was opened. And most important of all, the people dug their first irrigation ditch.

Today, the ditch over a hundred years old, and now passing through the center of the city still runs full much of the year supplying water for surrounding croplands. This one, along with others dug in those first years, established an irrigation system that would later be adopted by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation for all the mountain states. The success of the Greeley Colony inspired other cooperative efforts. Starting up similar types of communities at Longmont, Fort Collins and Sterling. The irrigation boom helped quadruple the number of farms in the region. And sketched out the basic canal system of Colorado's eastern slope. The farmers went even further and their efforts at landholding. They began fencing their property. At first, mainly to keep their crops from being trampled and destroyed by these beasts [picture of long horn cattle]. They're called just what their horns suggest. These, of course, are distant relatives of the early long horns that made up the great herds of trail-driven Texas

cattle which, in the middle 1860s, gave birth to an industry that lasted for almost 30 years. [actor cowboy] All right, head 'em up and move them out. [Narrator] By 1870, hundreds of thousands of longhorns had been driven up several well-known Texas trails. Including the Good Night Loving Trail that came up through Colorado. Wranglers, cattle bosses, cowboys, a third of them either Hispanic or black worked the large herds for many years. While many of the long horns were sold at rail heads as feeder cattle or for beef to satisfy a growing eastern markets, a great numbers of the animals were bought by northern stockmen to build their own herds for later profits. The cattlemen, in the beginning, had no grants or express permission to use this government land. The herds were branded and then simply released to spread up over the prairies. Many of the animals were never seen by their owners except at roundup time. For many

years, the range was open, unfenced and uncontrolled except as the cattlemen began controlling it for their own uses. His name, John Wesley Iliff, known far and wide as the great cattle king of the western plains. Here in northeastern Colorado were located most of his cattle operations, ranches and landholdings that extended for a hundred miles along the South Platte River. And most importantly, for shipping cattle back east near the newly built Union Pacific railroad tracks. Although in later years his residence was in Denver, John Iliff was often seen in his buckboard out here on the range heading for one of his cow camps. Especially was this true when his good friend Charles Goodnight was about to deliver to him another 25,000 head of longhorns from Texas. [actor portraying Mr. Iliff] What in the world you doing over here? [actor portraying Wes, cowhand] Mr. Goodnight sent me. I was hoping to catch you before you got all the way to Fremont's

Orchard. [Mr. Iliff] Anything gone wrong? [Wes] We got delayed over there at Sandy Creek. That thunderstorm the other night spooked the herd. About a thousand head of 'em scattered afar. It took us most the day to round 'em up. [Mr. Iliff] Rest of the drive go all right? [Wes] Well, pretty much as usual. Some of them homesteaders at the Kit Carson cut off down there started a down there with that new barbed wire. We're seeing more and more of it all the time. [Mr. Iliff] Yes I've heard about it, Wes. Over in Kansas, it's already started up range wars between the farmers and ranchers. [Wes] Was there anything we can do about it I mean besides cutting our way through it? [Mr. Iliff] In the long run, probably not. Lots of things are changing out here, Wes, with property and water rights high on the list. I'm afraid there'll come a day when this whole range will be fenced. We better get started for camp. I'm anxious to see the herd. I want to breed part of them with some new Durhum and Herford bulls that I bought. Should produce a heavier steer. [Wes] By the way, Mr. Iliff, Mr. Goodnight saw one of those new fangled refrigerated railroad cars over at the rail head. They say it keeps butchered beef cool all the way to Chicago. [Narrator] Homesteaders,

ranchmen, barbed wire, range wars. In between it all, a forgotten people. This is a Cheyenne war lance tipped with a finely honed blade, decorated with buffalo hide and eagle feathers. It was often used as an instrument of warfare. The lance, sometimes thrown in the vicinity of white men settlements, expressed the anger experienced by Cheyenne warriors against the danger posed by the white people to what the Indians considered to be their land and their way of life. On the lips of many of the tribal chiefs was the question "Why doesn't the white man keep his word?" By the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, Southern Cheyenne and Arapahoes had been a given joint control over a vast territory of unbroken buffalo range between the Oregon and Santa Fe trails. Land that included much of eastern Colorado. Ten years later, the same two tribes,

Under mounting pressure from the United States government, agreed to move on to a much smaller area known as the Sand Creek reservation. There was also the stipulation that the tribes would give up buffalo hunting and learn instead how to farm on 40 acre plots of prairie land. For many of the younger Cheyenne and Arapaho Warriors it was not acceptable. By 1864, Indian raids, white man retaliation, unresolved differences on both sides escalated into open warfare here in eastern Colorado. One such tragedy became known as the Sand Creek Massacre. At dawn on November 29, Colonel John Chivington and his contingent of Colorado cavalry volunteers made a surprise attack on Chief Black Kettle's and Chief White Antelope's encampment located on the Sand Creek Reservation. Throughout the morning, the soldiers with rifle and cannon, cleared Sand Creek for some two miles of its

defenders and completed the destruction of the village. The cavalry loss was eight men killed. The Indian dead estimated at something under 200. Two thirds of the bodies, counted later, were women and children. What happened at the Sand Creek reservation certainly didn't settle the differences between the Indians and the white men. In some ways it served only to further anger surviving warriors. To seek revenge at places like Fort Sedgewick, Julesburg and at Beecher Island. [music background] The words of chief White Antelope were like a paradox to this whole Indian problem. [Actor speaking as White Antelope] I have told my people that the white settlers are good people. That peace was going to be made. When I see the soldiers shooting my people, I do not wish to live any longer. Nothing lives long. Only the earth and the mountains. (End of part 03, OUR CENTENNIAL STATE)

[Beginning of part 04, OUR CENTENNIAL STATE: Crossties, Rails and Steam] [Train engineer] From the pressure on that. Run that down a little, will you please? That's right,

those are crank pins that greases it. I rebuilt this old engine, spent a lot of time on it. Rebuilt it back to the 1870 period. [John Rugg] Oh, it looks great! [Everett Rohrer, train owner] Yes, sir, it burns wood as it did in those days, or coal either one. Say, let's get up in the cab. [John Rugg] All right. [Everett Rohrer] John, let me have those. Put that in. Put some wood in the firebox, will ya, John? You see, this is part of his job. He does this because he sits over there and he's got to look after it to keep up steam and you can see we've got steam up now. (John Rugg) Oh yeah. (Rohrer) By the way, would you like to run the engine, John? [John Rugg] Oh, I'd love to. [Rohrer] Climb up there in the seat box. I'll tell you what you have to do. First thing you have to do, John, to make it move, you push the reverse lever forward. [John Rugg] All right. [Rohrer] ...like that. Then you take the air brake off, push this head like that and here is ????? (some indescernable words). [Train horn honks] All right. Now now here is the throttle.

Pull the throttle back - easy - and it'll start moving ahead [sound of train moving]. Now, keep moving. [John Rugg] All right. [Rohrer] You're going right along here, ok? Yeah, absolutely. [train moving and horn blowing along the track] [John Rugg] This is fun! All right. [Rohrer] Moving right along. [Narrator] How would you like to have an old locomotive like this call your own? Mr. Rohrer bought this steam engine, the tender, the passenger car, the baggage car and the caboose to help preserve part of this country's early railroad history. Such transportation became increasingly important to land development out here in the West as railways expanded in the early 1850s.

[actor] Senator, railway companies will agree to expand out west if Congress will not only give them a right of way but provide as well title to land on either side of the proposed route. You know as well as I, building railroads costs money. [Narrator] And with help from the United States government through land grants and federal loans railway companies did expand, laying new tracks westward while advertising their newly acquired land for sale in this country and even in Europe. Tens of thousands of Americans plus great numbers of newly arrived immigrants took advantage of the land sales to settle in the New Territories created out west. In Colorado, William Gilpin foresaw before most what eastern trade would mean to this newly settled area. [Actor speaking as William Gilpin] With the help of the railroad, Denver and Colorado could be the crossroads of the world. [Narrator] William Byers, through editorials and his Rocky Mountain News, expressed the same theme a year later. [Actor speaking at William Byers] The eastern railroad must pass through the South Platte gold

fields. And that's our city of Denver at the eastern foot of the Rocky Mountains will be a point which cannot be dodged. The officials of the Union Pacific Railroad, however, thought differently. They had no plans to spend great sums of money to run their tracks through Denver and across the high Colorado Rockies. Especially when their chief engineer, inspecting a possible route over Berthoud Pass in 1866, barely escaped with his life in an October snowstorm. In addition, the flooding of the South Platte River in 1864 and a declining production from Rocky Mountain gold mines had reduced Denver City to a quiet village. [actor] Denver? Why that town is too dead to bury. [Narrator] Suddenly to the dismay of people in Colorado, Cheyenne is chosen to be on the route of the Transcontinental Railway over the Rockies. Union Pacific steam engines arrived there in late 1867. Pushing further west to link up with the Central

Pacific Railway being built eastward from San Francisco. Finally on May 10th, 1869 from Promotory Point, Utah, a message was telegraphed to President Grant in Washington DC. With such cross ties and rails in place, people believe that the West was now firmly tied to the east. But was it? There were parts of the west that would continue to be isolated for years. Colorado territory, for example, was less than 10 miles from the Union Pacific line that ran through Cheyenne and yet by 1869 there was still no railroad switching mechanism connecting Colorado to the newly completed transcontinental railroad to the north. For purposes of trade with important supply centers and wholesale markets back east, Colorado was as isolated as it had ever been. For this man, John Evans, former governor of Colorado Territory, it was a dilemma that he and his Denver friends intended to resolve

by completing their own partially built railroad north to Cheyenne. It would be called the Denver Pacific. On July 2, 1869 he hired this man to complete its construction. His name? General William Palmer. [actor portraying Palmer] It might only be appropriate but much more functional as well in that it will allow us to put into operation more quickly the objectives you have in mind. [2nd actor portraying John Evans] I appreciate that General Palmer. I too am anxious to get started. Colorado desperately needs to link up with the Transcontinental Railroad in Cheyenne. It could well be the decisive factor that could bring us statehood. [Palmer] May I get you something, a coffee perhaps. [Evans] No, but thank you for your hospitality and for your patience through these long negotiations to employ your services. [Palmer] I too am sorry for the delays, governor. However I'm sure you can appreciate my predicament. As of today I am in charge of bringing not one but two railroads into Denver: the Kansas Pacific route through eastern Colorado and now your Denver Pacific line connecting with Cheyenne. I am sure there are those who will protest loudly

that a conflict of interests exists somewhere in these negotiations. [Evans] Let me assure you, General, that such arrangements as we have made are all very legal and as far as any local resistance by outside interests, well you know as well as I that for years William Loveland and Henry Teller have been trying to make Denver a suburb of their little town of Golden to the West. [Palmer] Yes I have heard a number of reports to that effect. [Evans] Well, their tactics haven't gotten anywhere. Why they can't even finance their own proposed railroad north to Cheyenne much less a route over the Rockies by way of Berthoud Pass. No, general with your help, Denver will become the main railroad terminal in Colorado linking up with the Union Pacific by way of Cheyenne to the Trade Centers of Omaha and Chicago and then of course with the completion of your Kansas Pacific tracks to our city, freight and passenger lines to Kansas City and St. Louis will be opened as well. Now, sir. When can you get started? [Palmer] I already have,

Governor. Cecil Lofton, my surveyor, has traveled the route again just yesterday. He estimates some 50 miles of track will need to be laid to complete the connection with Cheyenne. I venture a completion date within a year from now. That is if I can get the numbers of men and materials I need to do the job. [Evans] Well, if I can be of any help in that regard, General, please don't hesitate to call on me. Now I'd like to talk a bit about the contract and the (voice fades). [Narrator] On June 22nd of the following year, General Palmer sat down to write yet another of his many letters that kept his fiancee back in New York apprised of what was happening to him out west. [voice of Palmer] Denver was much excited today. The last spike on the railroad in the heart of the town was driven, poor creatures. It was an event indeed for them. They have been so long out of communication with the rest of the world and I suppose most of the children had really never seen a locomotive. [Narrator] With railway expansion came many improvements. Passenger cars not only increased in size to handle as many as 44 adults in

one car, but the comfort of sitting was also improved. Rock-over seats were introduced so that family and friends could sit facing one another while traveling. The seats were cushioned and covered with materials like this crimson plush. It made the journey out here to the west at least more enjoyable and less painful to certain parts of the body and the hard and sometimes splintered wooden feet of earlier years. The effects of Colorado's new railroad connections were nothing short of spectacular. New towns begin to spring up all along the railroad lines. These first railroads also gave cities like Denver the boost that they so desperately needed. Within only four years of completing the railroad into the Mile High City, Denver's population tripled in size. Its business also increased three-fold. The biggest impact of all, however, came with the use of these old conveyances

carrying at first as much as 10 tons of freight in each car. Inside such transportation, came west heavy building materials, furniture farm equipment, food supplies and industrial machines. To the east, what a variety of crops as well as cattle and sheep. There were even refrigerator cars made to keep cool a variety of perishable goods all the way to wholesale markets in the east. Important as well was the help provided by the railroad in rescuing the declining mining industry of Colorado. For the first time, the heavy high grade ores mined in Colorado could be shipped back east for special processing that made for higher profits. Local Mills could now be run economically as the cost of machinery, wages, food, clothing and fuel all fell sharply. Businessmen and politicians desiring statehood now voiced a new theme. How can we tie together the newly completed 200

miles of track in the northeast with a barren and unpopulated expanse of southern and western Colorado territory? Once again, it would be this man who would fulfill such a vision. [Palmer, actor] I had a dream while sitting here at the car window. I thought how fine it would be to have a little railroad a few hundred miles in length all under one's own control with one's friends. [Narrator] Palmer actually envisioned more than just a little railroad. [Palmer actor] Imagine the Rocky Mountain West with its own rail system helping to make the region almost self-sufficient by distributing food grown in our soil, minerals mined in our mountains and products made in our own factories. [Narrator] And the tracks of the general's railroad would run not east or west but rather north and south. Palmer planned his first segment from Denver to Santa Fe. And then further south through El Paso. And perhaps later even to Mexico City. It's little wonder that he named his little railroad The Denver and Rio Grande. By

October of '71, the new railroad reached Colorado Springs. Palmer's dream town that he helped organize, name, and in which he would later make his home. A year later, tracks reached Pueblo changing this sleepy adobe town of 600 in just a few years to a growing center of population for Southern Colorado. Suddenly, a panic of 1873 along with a direct confrontation with the expanding Atchison Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad Company blocked Palmer's vision of developing his little railroad south to Texas. He did, however see to the laying of tracks into some of the most rugged parts of the Colorado Rockies including crossing La Vita Pass and the Continental Divide at Marshall Pass. Elevation, ten thousand eight hundred forty six feet above sea level. More importantly, General Palmer pioneered the development of mountain rail systems with his vision and financial backing of what would be called the narrow gauge railroad.

Tracks, not the usual four feet eight and one half inches apart, but rather rails that were only three feet apart, then a revolutionary concept in railroad development. What it meant for mountain rail travel is reflected here above Georgetown, Colorado at an elevation of over 9,000 feet. This famous Georgetown Loop Railroad, finished in 1984, has been completely rebuilt so that today tourists can experience what the original narrow gauge railroad was like back in the 1880s. This relatively light steam locomotive on this narrow gauge track, pulling either passenger or freight cars, could not only power itself up a steep mountain

grade, but could also make 180 degree turns on curves so sharp that the locomotive would pass its own passenger or freight cars. The narrow gauge tracks were also much cheaper to construct than the standard gauge, especially up through the narrow gulches and mountain passes. It meant that Colorado mining towns were at last linked to a network of tracks that would lead to a reasonable balance between mining production and sales. There was little question in the minds of historians at the comic huffing and puffing of these narrow gauge locomotives had a great deal to do with the growth of the mining industry here as well as the founding and development of towns and cities in our mountainous regions. Such expansion of course would later lead to statehood and a five-fold increase in Colorado's population and wealth.

- Series

- Our Centennial State

- Episode Number

- Episodes 1-4

- Contributing Organization

- Rocky Mountain PBS (Denver, Colorado)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip/52-010p2p5d

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip/52-010p2p5d).

- Description

- Episode Description

- Features Episodes 1-4 Program 1-- "Early Trails" Program 2-- "Pike's Peak or Bust" Program 3-- "Go West, Young Man" Program 4-- "Cross-ties, Rails & Steam"

- Series Description

- OUR CENTENNIAL STATE, KRMA-TV's new instructional series on Colorado history premiered in 1986. Produced and directed by former KRMA-TV Instructional Designer, John Rugg, the series developed from the early migratory trails and takes students into present- day issues facing Colorado. Targeted for eighth and ninth graders, the eight 15-minute lessons can operate as a self-contained unit on Colorado history or can be used individually as part of an American history course covering the "Westward Movement." OUR CENTENNIAL STATE used on-location footage, dramatic vignettes, historical photos, and reconstructed graphics to tell the story of Colorado. A comprehensive teacher's guide was developed by Rugg to complement the video component. The guide included objectives, vocabulary, activities, summaries, teacher background, and pupil references. Because the series was a local production developed out of an indicated need on the Learning Services Utilization Survey, it carried unlimited rerecord rights for all school districts in Colorado.

- Date

- 1986-00-00

- Topics

- History

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 01:02:05

- Credits

-

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

Rocky Mountain PBS (KRMA)

Identifier: 001.75.2011.0877 (Stations Archived Memories (SAM))

Format: U-matic

Duration: 01:00:00

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “Our Centennial State; Episodes 1-4,” 1986-00-00, Rocky Mountain PBS, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed January 5, 2026, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-52-010p2p5d.

- MLA: “Our Centennial State; Episodes 1-4.” 1986-00-00. Rocky Mountain PBS, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. January 5, 2026. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-52-010p2p5d>.

- APA: Our Centennial State; Episodes 1-4. Boston, MA: Rocky Mountain PBS, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-52-010p2p5d