Age of Overkill; 1; New Weapons in the World

- Transcript

Doubtur For these races and faces of mankind Which you've been watching in the background There's a new world in the making With new weapons which are transforming it These as I shall soon be explaining are the weapons of Overkill Hence the age which they have shaped en soon perhaps may be destroying is the age of overkill. That's why I have given that overall title to this series of talks about world politics today and what the new forces in it are and where they're tending and what we can do about them. This is the first talk of the series on the age of overkill and how the peoples and leaders of mankind can save themselves from the idiocy of destruction. Let me, by way of warning, say that what I shall be repeating at the start of each of the talks. That I don't speak for any party or government,

for liberalism or conservatism. I don't place such games at a time when the stakes are life and death for all mankind. The time is running short for all of us. I speak as objectively as I can for the survival of humanity and the continued greatness of an open society in America. And let me start by saying that the world we live in is neither a graceful nor a nourishing world. Yet it is what it is. The Greeks used to have the myth of the Medusa Head. A coil of wild serpent so horrible to behold and when you looked at them, they turned you to stone. Our contemporary world is our Medusa Head. And we must face it even at the risk of being turned to stone. In W.A. Jordan's phrase, we're all of us double men. We live on two levels. On one, we cherish our private little universe with its fears and anxieties, its hopes for the future.

And another level, we're aware that there are forces in the world outside, that at any moment can pick up this private little universe of ours and crush it like an egg shell. Now my angle of vision in these talks will be clear if I tell you that recently I spent about a year living in India and traveling through Asia. I learned I hope to see the world partly through Asian eyes, through the eyes of formerly colonial peoples who fought for their freedom and established their nationhood, and now face difficulties and dangers hard for us to understand. But later when I was in Paris on my way back from India, back in the spring of 1960, I had a chance to see the world again through Western eyes. I attended that summit conference which didn't quite turn out to be a summit. And I got a chance to restore my perspective,

perhaps to get a double perspective, Western and Asian. I think the biggest thing I learned is that people don't think about the world, they feel. I learned the power of the irrational. I don't think that it's public opinion that counts in world politics. It's convictions and ideas. It's loves and hate and dispares. It's men's fears and their hopes that count. It's the myths that they live by and their dreams and their nightmares, their delusions and their obsessions, their actions and their passions. I can remember a professor who fled from Nazi terror way back in the early 1930s. His name, as I recall, it was Cantirovich. He was a great political thinker. I went to one of his lectures a long time ago. And while I can't remember much of what he said,

there was one sentence that I recall. He said, men possess thoughts, but ideas possess men. Ideas possess men in the sense that they enter into them, very much the way in which our New England ancestors used to think that spirits entered into women and possessed them, and made them do their bidding. Today in Asia and in Africa, and in the Middle East and in Latin America, one can see the hold that these vast ideas, these isms of all kinds, have on men's actions and beliefs. We've had a number of illustrations of the power and hold of such isms, such ideas, for ill and for good. For example, think of the young students and workers who defied the Russian military on the streets of Budapest, you recall, in that Hungarian revolution in 1956. In rational terms of saving their skins,

it made no sense, and yet they did it. Here is the heroism of youth, asking to be stretched and used for purposes beyond itself, ready to die for a free nation. In a similar way, think of the South Korean college and high school students being beaten in the streets of Seoul, being beaten yet marching on and on until they toppled the corrupt South Korean regime. Here again you have young people this time, not communist led, who showed themselves, ready to give up their young manhood for something closer to a genuine democratic regime. Again, this wasn't a rational thing, for youngsters who might want to play it safe, yet they did it, and because they did it, the American position in Asia has been a good deal firmer than it was, or think of what happened in Tokyo. When President Eisenhower had to cancel

his projected trip to Japan, instead of him, his press secretary Jim Heggardy came along and he came there first to reconnoiter the ground, and he was caught up in a passionate crowd of young people he was surrounded by a sea of faces, each of them a mask of hate, and finally he had to be rescued by helicopter. These hate-filled youngsters felt just as passionately nationalist as did the heroic Hungarian and South Korean freedom fighters. It was the non-rational in the service of the totalitarian idea to which they were submitting. These youngsters were willingly putting on an intellectual straight jacket, and yet by doing it, they made history. Finally, take the Castro Revolution in Cuba. Here was the bearded leader, and here were the bearded young men starting with an idealism very similar to that of the Hungarian and South Korean youth,

enduring much, hoping for much stretched beyond themselves, and then their fanaticism was used for very different purposes by the very regime from which they'd hoped for so much, as often happens in history the revolution devoured its children, and raised up ghosts that would not be settled for a long time to come. Thus it happens in the enchanted wood where men seem half under the spell of their dreams and hatreds and passions, like a medieval painting of fabled animals in a bestiary. It's in the nature of this enchanted wood, that the very dreams and passions that start by liberating man may end by imprisoning him. Men dream of liberation and progress, and they end by repeating the ancient story of man's inhumanity to man. Now I owe it to you very early in this series of talks,

to tell you about how I view overkill. It's a term I take from the military men. They speak of the overkill factor, by which they mean how many times over can you kill people who form your target? General John Madaris, who used to head up weapons development for the US Army, estimates that the overkill factor on both sides is about 30 or 35 now. Each side now has in its nuclear stockpiles enough explosive force to kill every man, woman, and child in the world 30 or 35 times over. There are four levels from which each side hopes to be able to launch its weapons at the other. One is from the ground itself, which means from the rocket sites scattered around the United States at Cape Canaveral and elsewhere,

and since these are sitting ducks as targets themselves, they're now being buried underground. The second is from the air, which is why America has developed its strategic air command, with bases both in the United States and abroad, in Spain and Morocco and England, in Turkey and Iran and Pakistan, with half the planes capable of being in the air on a 15-minute warning. The third is from subsurface craft, below the waters of the earth, which is why America has developed its network of atomic-powered submarines equipped with Polaris missiles. This revolutionizes the nuclear pattern, making it mobile, making the system of overseas bases far less important than before, removing the necessity for the far-flung military alliances that the United States has had to maintain all over the world.

And the fourth is from the vast spaces above the skies, which is why both sides have been exploring interstellar space with rockets of every sort. It's why monkeys have been shot into space and have been retrieved, like subhuman pioneers in areas where someday human beings may be living, coming back perhaps not quite so happily as the monkeys come back. It's why astronauts have been trained for the longest journey into nowhere that man has ever undertaken, always with the aim of achieving what Lyndon Johnson once called that position in space, from which one may be able to train weapons on any spot on earth, on earth, at will. Now, of course this is the ultimate and the unthinkable in weapons. If each side achieves it,

then the final stage of deterrence will have been reached. Each will be able to exterminate the other from space and will hope by that fact to be invulnerable. There's one other hair-raising fact about the new weapons. It's what we now call the weapons generation. The thing the military experts say is that a weapons generation now is five years long. Professor Henry Kissinger has shortened it and he says it's three years. That's to say, every five years or even every three years, new weapons come into being. They come off the drawing board. These new weapons make the old weapons archaic. And the men who developed a psychological stake in the old weapons have to be pushed aside by men with a stake in the new ones. Thus the turnover rate, both for weapons and for weapons experts, is unparalleled in the whole history of war. And all of this has arisen from two decisions

that were made by political leaders in two earlier political generations. One was made by Franklin Roosevelt when he received a letter drawn up by Albert Einstein and Leo Zillard. And this said in motion the Manhattan Project. And the second decision was made by Harry Truman. That fateful decision when he decided to drop the bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, instead of making a demonstration of its destructive power on a barren island somewhere. Those two decisions ushered in the age of overkill. And we are now launched on a great debate about what to do to prevent these weapons from being used. But we must first ask what it is that these new weapons have done to our world. I contend that they have cut the foundations

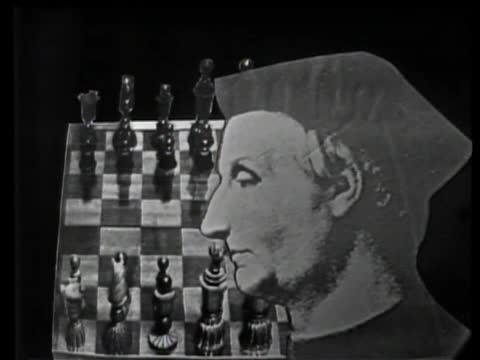

from under the world of nation-states to which we've grown accustomed, that they've undercut the whole system of classical world politics. When the system of nation-states first emerged in Europe during the Renaissance, a Florentine called Machiavelli wrote a book, called The Prince, in which he set down the main features of this new world, with a coolness of precision and a mastery that had never been paralleled. Machiavelli was the theorist of power. He described power just the way that Harvey, for example, described the circulation of the blood. And in giving us a kind of anatomy of power, a grammar of power, he also clarified for the world the relationships between nation-states. They were the relation of animals in the jungle, or to change the figure, they were pawns on the chessboard of politics.

Much later in the 19th century, there's a story about a British statesman getting up in the House of Lords. It was a debate about Turkey. Someone had called Turkey England's permanent friend, and the statesman arose, and he said, my lord, England has no permanent friends. England has no permanent enemies. England has only permanent interests. Here you get the system of naked self-interest, described in terms of what we have come to call Reason of State. It was an idea that came out of Machiavelli, that there are two kinds of morality, one the morality of the individual, the other the morality of the state. You see, the state is able to do things for reasons of state that the individual could never do. This is the first element in what we might call the anatomy of the classical system of world politics,

which I've said is being destroyed. But there are other elements, for example, the cult of power and the scarcity of power. The idea used to be that power is so scarce that each nation must always pile up more and more and can never have enough. And then another element, the prevalence of fear, the whole system is saturated with fear. The fear of nation states for each other, the fear of the generals, the fear of the ruling groups for each other. And then another element, the idea of national sovereignty. The idea that each nation is so sufficient, that it has complete power, and that this sovereignty cannot be touched. And then the notion of the balance of power, on which the whole system of alliances is based. One nation watches the other getting more power, and so it's necessary to make alliances that will balance the power of the other nations.

And finally, of course, war itself. War is the moment of truth. When you test your accumulated power, and find out whether you're able to survive and conquer or whether you go under. There was a great German military theorist, General von Klausowitz, who put it all in a nutshell when he defined war as the continuation of policy by other means. This sums up the system of classical world politics. This system is now passing because of overkill. And why? For two reasons. The old assumptions about national power are no longer true. And second, war in its modern form is too high a price to pay for winning that old game of power politics. Yet the game is part of any world of nation states. Now, let's first talk about the assumptions about power.

The members of the nuclear club, and they're growing. Each one of them is trying to build up more and more power, yes. But the fact is that each of them already has more power than it can use or dare use. As for the nature of modern war, it's no longer an arms race that we're in, let's face it. I call it a vicious spiral, a deadly spiral of missiles and fear. One side piles up missiles generating fear on the other side. And out of that fear, it piles up more missiles which generates more fear on the first side and so on in an endless spiral. This means that the whole system of war as an instrument of national policy has been undercut. I don't mean that a nuclear war is impossible. Unless there is real disarmament under world law,

I would say that it's highly probable within the next decade that we'll have nuclear war. Oh, we may blunder into it by accident that we may be scared into it by each other's nuclear shadows. We may find that through the diffusion, through the spread of nuclear energy among more nations, with more chance of somebody pushing the button that all of this is possible. What I'm emphasizing is that this can no longer be a matter of deliberate national policy. The fact is that power has become powerless. The fact is that its use has become a form of world psychosis. For over 15 years since Nagasaki, these weapons have not been used. There are a number of areas in the world which I call nerve and areas, where one side of the other feels so deeply about them. Say Berlin, or the Congo, or Cuba. These nerve and areas where one side of the other

feels so deeply that if the other would attempt to move too far, it touches that raw nerve end and might result in war. These are areas where, in effect, each side is saying to the others, stay away, don't touch me. In this sense, the missile spiral is a kind of symbolic game, a game in which there are counters that stand for something, stand for nuclear weapons, yet what they stand for is something that cannot be used. It's a little like a child's game, all compact of fantasy, but what a grim kind of game it is. Now let me sum it up this way. The great powers are caught between lethal weapons they do not use, and positions from which they cannot and will not receive. What could be more dangerous or more agonized? How do the world get into this plate?

How can it get out? That's what the series of talks is about. As far I've been talking of only one of the great new forces in our new world, this deadly missile spiral, and what it has done to destroy the old world. Now let me make it more complex by talking of two others. The second force is the new revolutionary nationalism that has come to the old continents of Asia and Africa and made new continents out of them. It's a grim joke that history seems to have played upon us. Adjust at the moment when the nation-state has become useless for survival and an incitement to nuclear war. A host of new nation-states appears on the scene, bringing with them new nationalisms in their embittered desire to revenge themselves for centuries of oppression. And then the third force is the grand design of world communism. It's the rise of two powerful new nations, Russia and China,

as part of revolutionary communism, with a deep split between them, yes, but both of them children of Marx's dogma, both conquerors with a book, both confident of the forces of history by which they will ride to world empire for communism. All three of these, the deadly missile spiral, the new racist nationalism, the grand design of world communism, all three interact to change the outline of the world we live in. Archibald McLeish has said in one of his poems a world ends when its metaphor has died. Well, the chessboard metaphor of Machiavelli as a system of pawns to be moved about, that has died. There's a new kind of game being played by military and political experts on nuclear weapons. It's called Games Theory. And what it amounts to is an elaborate mathematical calculation of how each side can outface, outthink, outbluff the other

in the confrontation of weapons, setting up a delicate balance of terror, so that each has the weapons for deterring the other from making the first strike, and enough extra to retaliate and knock out the other if it does attack. No Kafka, no George Orwell has yet arisen who could adequately portray in fictional terms this nightmare world that the missile spiral has created. Perhaps its quality of terror outruns the imagination of fiction maybe only the cold realistic analysis can do justice to it. There's one such realistic work that's been written. Herman Kahn's book. It's called On Thermonuclear War. There are many things in it that have stirred the wrath of critics who believe the Kahn is too cold-blooded about it all. For example,

he has a table in this book that he calls tragic but distinguishable post-war states, in which he figures, in how many years we would be able to rebuild our economy on the assumption that we had, let's say, two million Americans killed, or five million, or ten, or twenty, and so on, right up to 160 million people killed in America. And there's a section which he calls, will the survivors envy the dead, in which he concludes soberly, that they will not, that we'll be able to go on with some kind of normal life. Now, what's at fault is not Kahn's analysis, which is a closely-reasoned one, and confronts the Medusa head. What's at fault is the lack of will on his part, or on ours, to achieve a disarmed world under world law. The surprising fact thus far, is that for more than 15 years since Nagasaki,

these weapons have not been used. Thus far, it has been because men have recoiled from the prospect, and perhaps there's some hope in that. For a literary peril, we may perhaps have to go back to the figure of Dr. Faustis. When the devil came to him to make that Faustian bargain, suppose that some apparitions, such as Fascinated Gerta, and before him Christopher Marlow, suppose that apparition were to come to man, and say, here it is, here's your heart's desire, the dream you've been dreaming. This is what the philosophers have speculated on. This is what your young men have dreamt of. This is what your scientists have charted in the long vigils of the night. This is what your mathematicians have calculated, and your poets have spun in their Gossamer visions.

Here is your utmost dream, your Helen, your gleaming city of the mind. Here it is, yours to possess and command. You've wanted the ultimate of power and mastery. All right, here it is. Now you can put it into execution and destroy those whom you hate, and incidentally, destroy the world that you have so painfully been building up over the centuries. What are you going to do about it? Will the historian of man's bloody road record that at this moment, when the Faustian question was put to man, instead of grasping for the power that he had dreamt about, man faltered, in that moment of faltering, I believe, that man may have moved beyond the power principle, by which I mean that war, the system of Machiavelli has now become the acme of the senseless. It can no longer be used as a principle of order

in a world of nations. Next week on the Age of Overkill, the Grand As University Professor Max Lerner will discuss the delicate balance of terror. This program was produced for the National Educational Television and Radio Center by the Lowell Institute Cooperative Broadcasting Council,

WGBH TV Boston. This is NET, National Educational Television.

- Series

- Age of Overkill

- Episode Number

- 1

- Episode

- New Weapons in the World

- Producing Organization

- WGBH Educational Foundation

- Contributing Organization

- Library of Congress (Washington, District of Columbia)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip/512-td9n29q78w

- NOLA Code

- AGEO

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip/512-td9n29q78w).

- Description

- Episode Description

- Lerner devotes the first program to an examination of the meaning of nuclear weapons in an era when each of the world blocs possesses enough destructive power to kill the entire population of the world thirty-five or forty times over. His main point is that we no longer live in an era of power scarcity, but in one of power surplus. (Description adapted from documents in the NET Microfiche)

- Series Description

- In The Age of Overkill, Mr. Lerner concerns himself with five major forces in our contemporary world: nuclear weapons with overkill potentials; the nation-state explosion from which dozens of new nations are emerging; the passing of the old imperialism and its replacement by the two great power masses, the democratic and the communist world blocs; the increasing prevalence of "political warfare" - assault by means of ideas, economic aid, culture and the enticement of new nations; and the UN and its growth as a transitional force. From his consideration of these forces emerges the central theme: the classical system of world politics is being undercut; war as part of the power struggle is suicidal and therefore, no longer possible; the world is moving - and must move faster - beyond the power principle. The Age of Overkill is hardly light viewing and Mr. Lerner does not attempt to make it so. He is deeply aware of the seriousness of the subject and deeply concerned over its implications. But he is neither a pedant nor an alarmist. His own stimulating delivery is augmented by the judicious use of excellent film clips and slides. The Age of Overkill was produced for NET by WGBH-TV in Boston. This series consists of 13 half-hour episodes that were originally recorded on videotape. (Description adapted from documents in the NET Microfiche)

- Broadcast Date

- 1961-12-03

- Asset type

- Episode

- Topics

- Education

- Global Affairs

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:30:00

- Credits

-

-

Director: Hallock, Donald J.

Executive Producer: Harney, Greg

Host: Lerner, Max

Producer: Kassel, Virginia

Producing Organization: WGBH Educational Foundation

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

Library of Congress

Identifier: 2036559-1 (MAVIS Item ID)

Format: 2 inch videotape

Generation: Master

Color: B&W

-

Library of Congress

Identifier: 2036559-2 (MAVIS Item ID)

Format: 1 inch videotape: SMPTE Type C

Generation: Master

Color: B&W

-

Library of Congress

Identifier: 2036559-3 (MAVIS Item ID)

Format: U-matic

Generation: Copy: Access

Color: B&W

-

Library of Congress

Identifier: 2036559-4 (MAVIS Item ID)

Generation: Master

-

Library of Congress

Identifier: 2036559-5 (MAVIS Item ID)

Generation: Copy: Access

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “Age of Overkill; 1; New Weapons in the World,” 1961-12-03, Library of Congress, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed August 6, 2025, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-512-td9n29q78w.

- MLA: “Age of Overkill; 1; New Weapons in the World.” 1961-12-03. Library of Congress, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. August 6, 2025. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-512-td9n29q78w>.

- APA: Age of Overkill; 1; New Weapons in the World. Boston, MA: Library of Congress, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-512-td9n29q78w