Kennewick Man On Trial

- Transcript

The discovery of Kennewick Man along the Columbia River has stirred a controversy. It's a controversy that has put Kennewick Man on trial. At issue is who can lay claim to Kennewick Man today. Nine thousand years after his death, Northwest Public Television presents Kennewick Man on Trial. Hi, I'm Stacy Hall. The ancient remains known as Kennewick Man were discovered along the banks of the Columbia River by accident four years ago. The discovery has sparked a debate from Washington State to Washington D.C. Just who has a right to these remains? Scientists, lawyers, Native American leaders, and government officials met recently on the campus of the University of Washington to give their view. We'll have their panel discussion coming up. But first a little history behind the controversy. As hydroplanes roared around the Columbia River for the 1996 Columbia Cup,

two young fans discovered a skull buried in the muddy banks. Shortly after the find, Tri-Cities anthropologist Jim Chatters sent a bone fragment to be tested. He learned Kennewick Man is about 9000 years old, one of the oldest skeletons discovered in the United States. This is a model of what Kennewick Man may have looked like. The importance of the find sparked a battle over the rights of the ancient remains. Native American groups say Kennewick Man is undoubtedly one of them. They argue further study goes against their religious beliefs, to leave the dead undisturbed. A group of five Native American tribes are seeking repatriation under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990. I will not subject sacred ancestral remains to be destroyed to produce scientific data. Eight anthropologists filed suit four years ago to stop the return of Kennewick Man to

the Mid-Columbia tribes. The scientists want more time to study the bones. The researchers argue no proof exists that the skeleton is related to any modern-day tribes in the Mid-Columbia. And the scientists say the bones can shed new light on how North America was settled and when. Washington Congressman Doc Hastings has proposed to change the law to make it clearer, research comes first. And if we have to go through this process every time to try to get some sort of scientific study of remains, I think we're we're selling ourselves short. I obey ancestors. In addition to Native Americans, the Norse pagan group Asatru Folk Assembly also claimed ancestral ties to Kennewick Man but have recently dropped out of the legal effort to claim the bones. On January 13th this year, the U.S. Department of Interior announced it has confirmed Kennewick Man is Washington's oldest resident.

We believe that Kennewick Man was born, lived out his life, and died in this part of the country about 9000 years ago. Because the remains are dated before the arrival of Christopher Columbus 500 years ago, the federal government has declared Kennewick Man a Native American under the NAGPRA law. You look at it scientifically, it is possible for the structure of the cranium and other parts of body to change over 9000 years. So in fact it may be that there is a biological connection between Kennewick remains and modern Indians. And just last month, the Department of Interior decided to go ahead with DNA testing on Kennewick Man to determine his cultural affiliation. We believe that further testing is not necessary on this, on these remains. Because of the sacredness of these remains and because of what this individual represents to us and means to us as tribal people. Scientists are pleased with the decision to conduct DNA tests. They say the more we

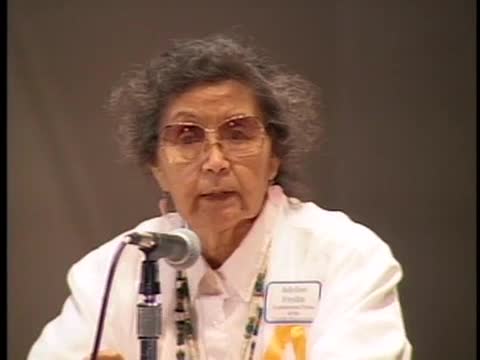

can learn about Kennewick Man, the better. Kennewick Man's remains are now at the Burke Museum, where they will be cared for until a final decision about them is reached. This hotly debated issue prompted the Burke Museum to hold a lecture series called Kennewick Man on Trial. The museum invited a number of experts to give their views on the controversy. Marcy Sillman of KUOW Public Radio moderated a panel discussion which included all the speakers from the two-day event. The panelists were Adeline Fredin, the tribal preservation officer for the confederated tribes of the Colville Reservation; Timothy McKeown, a team leader for the national implementation of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act at the National Park Service; David Meltzer, a professor of anthropology at Southern Methodist University and executive director of SMU's Quest Archaeological Research Fund which supports research on North American Paleo Indians; Rebecca Tsosie, a

professor of law at Arizona State University-Tempe and the executive director of ASU's Indian legal program; Joseph Powell holds joint post as faculty member in the Department of Anthropology of the University of New Mexico, curator of physical anthropology at the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, and forensic anthropology consultant for the state of New Mexico; and Anne Stone, an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of New Mexico. The moderator asked each panelist to summarize the presentations they gave for the lecture series. This is something that is, affects -- excuse me -- all the tribes in the nation. It's not something that's just unique to the tribes that are involved in this case right at this particular time. And that's one thing that we always remind ourselves is that the responsibility that we have been in representing tribal rights is

something that we constantly remind ourselves that it's it's others out there too that will suffer, may suffer, or stand to suffer because of the way that this case is being handled. The other thing I explained is that I came from a very traditional background. My grandfather was the last recognized chief of our tribe, and it's something that I don't normally talk about. Not not because I'm ashamed of it, it's just that I have more respect for him than to constantly bring that up. Excuse me. My grandmother was a traditional leader in reference to her role as a spiritual leader, as a counsellor, as a comforter to the people. And my dad, my dad had a different role in his, with

his tribe. He's a Methow, was a Methow, and he did running between tribes, and his grandfather before him was lead runner in the hunting parties. I explain this because I wanted the scientists to understand the traditional way of life and to try and understand the traditions versus science. I also explained that there is a place for science. There's a real need for good science and tribes normally have a need for that. At least with our tribe, it's not unusual for us to look for that kind of information that explains our hunting territories or fishing territories and to put a place in time to those

practices. We have volumes and volumes of documents that were produced because we were interested in understanding our own people. I want to say something here that wasn't said the other night, and it may help more of you understand a little bit more of the Colville tribe. It's that we were the first in Indian country to have a repository where the artifacts came back to the reservation and are stored there for the tribes to be next to and to be comforted by. We also run contracts. We have a contracts in the Walla Walla Corps of Engineers, Seattle Corps of Engineers, Bonneville Power Administration, Bureau of

Reclamation. I think currently right now, we're running probably twenty-seven contracts. We're normally involved in, in the front line so to speak with the Colville tribes in reference to how do we represent the other tribes in reference to cultural resources issues, management, protection, conditions, whatever they might be. I just wanted to let you know that. Thank you. Thank you. Timothy McKeown. Just very briefly, to summarize what I talked about last night, NAGPRA was passed in 1990. It blends together four major facets of federal law civil rights legislation. Congress recognized that there was unequal treatment of Native American human remains vis-a-vis those of other groups. Indian law, that it's founded on the government-to-government relationship between the United States and Indian tribes.

Property law, that the key piece of it is to determine who controls the objects that are discovered or in the museum collections. And lastly, administrative law, the so-called white tight, white tape we talked about a little bit. Three primary sections to this statute: one that deals with excavations and discoveries on federal and tribal land. That's the piece that we're dealing with here. It requires that if there is a removal of any objects that are covered by the statute, that that removal be done pursuant to an Archeological Resources Protection Act permit. That is, that the individuals have to be trained archaeologists, have a research design, follow that necessary protocol. The second facet of the law deals with trafficking. It forbids sale of Native American human remains and then cultural items as well in certain circumstances. And then the museum collection provisions that cover any collections held by federal agencies or

museums that receive federal funds. Thus far there have been relatively few discoveries on federal or tribal land. On the museum collections, notices have been published to make possible repatriations covering about 18,000 Native American human remains and about 300,000 funerary objects. Regarding the Kennewick case, since the original discovery of those remains in 96, purely from an administrative perspective, there's a couple precedents that have come out of that thus far. The first is that it provided a paired set of decisions, one regarding these particular remains that we're speaking of that may or may not be 9300 years old, depending on the information we have, that the judge has, the magistrate has determined that that initial decision to repatriate or to have the disposition to the tribes by the Corps of Engineers was arbitrary and capricious.

And then a second set of decisions regarding other individuals from that same general area at about the same time that neither the plaintiffs nor the court have challenged. The second important precedent is regarding the timeliness of decisions. The magistrate seems to feel that those decisions need to be made in a timely fashion and has actually set a deadline for those of March of next year. At this particular moment, the decision-making process is progressing. No decision has been made by the Department of the Interior, but the relevant decisions are whether this individual is Native American, following the statutory definition that, to clarify it, would be of or related to a group of people that resided within the area of the United States prior to the documented arrival of European colonists. If that individual is identified as being Native American, then to follow through the procedure to identify what the disposition should

be. First choice would be to a lineal descendant. Second, if it was on tribal land, it would be to the tribe. We know that it's not on tribal land. Third, to the culturally affiliated tribe, that is, a tribe that can show a relationship of shared group identity with these particular remains. And if not that, then to the tribe whose aboriginal territory these remains were discovered, either as determined by the Indian Claims Commission or the U.S. Court of Claims or other sources. And if none of those, then it would go into a category called "unclaimed". And I think that pretty much summarizes it. Thank you. David Meltzer. Well, I sat down and made a list of everything I talked about over the 60-odd minutes that I was talking earlier, and it's kind of depressing because I only told you folks about nine different things is all. But I managed to stretch it to 60 minutes. But here's the five-minute version. The five-minute version is that the first

people to come into the New World came in during the Pleistocene, during the Ice Age, at a time when the Americas were very, very different than they are today. The current archaeological evidence would suggest that we have at least two separate migratory pulses or waves coming out of northeast Asia, though I think it's important to add that we're not necessarily talking about specific discrete events that occurred one time, but rather a pulse or a wave might actually represent a dribbling over or a flow of people, because as we mentioned earlier, there's really not a lot of barriers to traffic between Asia and America. In North America, the earliest known complex that we have is Clovis. It appears archeologically around 11,500 years ago, and it's all over the place. It springs like dragon's teeth out of the ground. The movement of those folks is really quite interesting to

us, because it tells us something about the ability of native groups to very rapidly move through a complete and, at the time, unknown and empty landscape. And we talked about issues of the demographic conditions, the efforts to maintain mating networks, the efforts to maintain information flow and information exchange, and talked about landscape learning. I also made the argument, and again this was not based on a whole lot of really strong evidence, that in fact what we have is a population that moves fairly rapidly through the landscape and then settles into different areas or different regions of the continent. And once they settle in, I suspect that we have geographic isolation, reproductive isolation of these populations, with not a lot of interaction at least early on. I think later on in the prehistoric sequence, there is in fact

a resurgence, if you will, and a re-establishment of gene flow. I then ended by noting that I do not see a French connection to the New World. I do not see Europeans coming across the North Atlantic archeologically, and I finally ended on the point that Kennewick doesn't surprise me at all. The fact that it doesn't look like contemporary Native Americans doesn't mean anything to me as an archaeologist, and it certainly does not mean that it's not a Native American. I think it's quite clear to me that Kennewick is a Native American, and I think it's quite clear to me because I understand that over the last 9000 years there's been substantial gene flow, selection, evolution, and I'll stop there because that's all I can remember. You all bring up about 50 questions but I'll let everybody summarize. Rebecca Tsosie. I basically focused on the legal and moral controversy over the disposition of this set of ancient remains, and

I started by talking about the legal status of native people in this country and the special relationship that they have with the federal government which is premised on a duty of the federal government to protect their rights, the trust responsibility, and that then was the basis for NAGPRA. In terms of the actual litigation in this case, Monnicksen versus United States, I discussed the, the legal issues in that case, and primarily of course, the main legal issue is, are these remains subject to disposition under NAGPRA, and if so, is there a contemporary tribe or tribes that can serve as the appropriate entities to return those remains to? It was my opinion, reading the statute and regulations in the context of what's happened here, that this set of ancient remains definitely fits the definition of a Native American cultural item. I just don't see a controversy about that. The age of the remains certainly justifies that.

In terms of, you know, whether or not some contemporary group or groups is entitled to claim these remains, again it is my opinion that, yes, the cultural affiliation standard under the statute tells us that we can consult tribe's own oral histories and traditions and sort of geographical context in claiming this ancient person as their ancestor, and so I do believe that that should be read in that way. I did suggest that the court may not agree with that. And certainly there are other ways to claim the remains under the statute, aboriginal title being one of them and a close cultural relationship that doesn't necessarily amount to a cultural affiliation being another. In case none of those standards is met, I then explained that my impression is that the set of remains does not fall within the designation of culturally unidentifiable remains. It just doesn't fit the definition

because they are excavated after the statute and they have a geographical context. But nor are they unclaimed human remains because there are contemporary claimant tribes who have claimed this set of remains as their ancestor. So what should happen to the remains at that time is sort of the normative question that I addressed. And I talked about the tension between sort of the scientific interest in the remains and what native people are claiming is sort of their cultural interest in the remains. And it's my opinion that that NAGPRA as a policy statement weighs in favor of the native claims, that really there isn't a comparable protection for them in society, that they're not, you know, their claims just don't fit under the constitutional or common law structure. And in terms of the scientific interest, I, it's my opinion again that it's sort of a way of knowing the world, much as Native American people know the world in a different way. But there's nothing that necessarily privileges science in that task. It's certainly a field that's open to interpretation of

evidence and changes through time, so it's not as though we can even ascertain a truth that's consistent for all purposes and for all time. And finally I concluded by sort of explaining the political context of NAGPRA and repatriation claims globally among indigenous peoples as being a way to sort of reject the very negative consequences of European imperialism and colonialism on Native people, that basically denied them their human rights to protect their ancestors and their, you know, their connections or fundamental cultural connections, and talked about that as sort of a certain expression of modern political identity, rights of sovereignty and self-determination, that do have a basis in international human rights law and are tied to the norm of cultural integrity. And so given the three sort of views that we have, the world heritage theory that all of this belongs to the world, or cultural nationalism that all belongs to the nation state, or alternatively the cultural rights claim

that is advanced by indigenous peoples, I suggest that that is in line with the contemporary international law as it stands in human rights law, certainly consistent with the spirit and intent of NAGPRA. And it was my very fervent hope that we will not backtrack as a society on the advances that we've made so far. Thank you. Joseph Powell and Anne Stone, you gave your presentation together. Do you want to split up a summary, or whatever you want to do it. Let's do it the same way. We'll try, you're going to get the, the five-minute version back and forth here. We gave a presentation today on the construction of race from both the genetic and skeletal perspectives, and the whole quiz, question of where Native Americans came from has been one that's been around since the 16th century, as have our ideas about human variation. Traditionally, as early as the time of Aristotle, people wanted to classify human variation and place people into categories as a way of organizing their world.

Out of that, during the 19th century came a view that there were three main races, which were typified by differences in skin color and other sorts of phenotypic or or physical features. In the 1920s, those were sort of, there were a number of different approaches to that, that, that became sort of embedded in American anthropology, and it's not until recently that people began rejecting the whole, or questioning the whole idea of do races really exist, and part of that depends on the, the approach from genetics. So when we talk about genetics today, or when biologists talk about the idea of race, for example in a race of fruit flies or something, usually they're talking about subspecies, which is a concept that within a species there are geographic groups that don't interbreed with other geographic groups.

When we hold that standard, it's also, it's also not a common term, I would say, that's used in biology or in anthropology today in the biological sense, because it's a very ill-defined taxonomic concept. It's, it's not particularly useful, but if we use that standard to look at humans today, we find that we don't see great isolation between groups, we don't see clear boundaries. Instead, human variation is spread in clines. It's continuous. There's again no clear boundary. Also, when we look at humans as a group and compare them with our closest rela-, relatives the great apes, we have very little variation as a species. So essentially genetics finds the concept of race in humans

completely not useful or real. So that race is more of a, well, it is in our society a cultural concept or construct. When ancient remains or modern remains are discovered, we're still asked by society to place those into some kind of category to make an assessment of their biological or racial affinity, and that's exactly what happened in the case of the Kennewick remains. And it's sort of ironic that many people who do forensic anthropology are fairly accurate in classifying individuals, and that's in part because of the history of coloniz-, of European and other non-native peoples and their arrival in the New World, because they brought with them a range of variation that was sort of extreme from the areas that they came from. So we have an artificially divergent view of human differences and variation. The other problem is that you can, can come up with average values of what different groups of people around the world look like but,

and that may represent those kinds of differences people are interested in, but in reality around each of those averages, there is a wide range of vari-, of variation, and that variation overlaps significantly. So really ultimately what you're being asked to do is to take one individual, rather than looking at a whole population, one person and see which group that, that person comes closest to. That means that it may come closest to the mean of one, yet still be within the range of variation of two, three, or four other populations. So it becomes a very tricky and difficult issue. What we find with genetic data and skeletal data is that about 80 to 90 percent of the vari-, or roughly 90 percent of the variation that we see in human beings is found within any one race, and only 10 to 11 percent of the differences are between races, and that's been well documented in a number of scientific studies. Then I touched upon what we know from genetics about the peopling of the world and in particular about the

first colonization of the New World. I think it's very clear that the Americas was first colonized by people from Asia, probably in one to two waves. The diversity that we see in Native Americans today, many of those DNA types are found in populations in Asia, most commonly in central Asia. There have been various hypotheses about when these different migrations may have occurred. I would say now we, the consensus is probably that there was one to two migrations that perhaps occurred 20 to 30 thousand years ago, although genetics, I explained, is, is probably not the best source of dating for that type of event. I think archaeology is probably going to tell us more in that

case. When we're, we're asked to look at ancient skeletons like the Kennewick remains, we then get one little small slice of prehistory and the past. And we put that together with many other individuals from North and South America, we can get a much clearer picture of what life was like and what those folks looked like. Despite different kinds of artistic reconstructions of the faces, ultimately we have to rely on scientific approaches and statistical analyses to come up with ideas of probability of which group this person most closely resembled. What we found in the case of the Kennewick remains was that this was a man who lived a life of 45 to 50 years when he died, that he had suffered a number of injuries throughout his life, including an injury from a projectile point. He had been fairly robust and had a relatively rough, coarse diet, given the dental wear that we saw.

When we assessed his skull and the physical features that he seems to express, he is different from all modern peoples. He, his probability of being included in any one modern human group is virtually zero. Which raises some interesting questions about where he fits in historically. That may represent the fact that he's from a population that left no surviving descendants, but it's much more likely, based on my analyses and in my scientific opinion, that this individual probably originated from a source population in Asia, given that the closest modern groups that, he's closest to modern groups from Polynesia, the Ainu and other peoples of Asia, and that over the period of time after colonization, as Dr. Meltzer pointed out, that significant forces of evolution, such as genetic drift and natural selection, had an impact on the biology of these ancient people. So you can start off with, early in time, 15 to 10,000 years ago, people that looked significantly different from any modern people

anywhere in the world and ultimately, through evolutionary process, can, can end up with people that we see as native peoples found today. The same thing applies to ancient skeletons in other parts of the world as well. Well, I feel like the judge, I feel like Solomon here. What I keep thinking as all of you speak is that there's a lot of different ways to define what truth is. And I think Rebecca said a phrase, "a consistent truth" and maybe more to the point is, what is truth, and what is the truth to different people, is at the, the basis of here, of this... I wanted to ask Adeline Fredin a question. You, for your tribe, you direct the history and archaeology program and you mentioned that the Colville are not opposed to good science. For you,

where do, do science and your tribe's history intersect? Is there a way for science to respect your history and culture, and has it done that so far? We've been real lucky with, with a lot of the work that has gone on here lately. One of the things that, I think, that most tribes stand to benefit by science is a real clear understanding of their own people. We have information going back 5000, 7000, 8000. And it's throughout the territory for the, not for all of those tribes are comprised with the reservation, but at least the ones that we can reach through the kind of programs that go along the Columbia River or with, on federal land, something like that.

We've been real fortunate. Science is, is an absolute kind of thing. I know there's lots of theories and especially you're working in theories, the three scientists that are represented here. But you mentioned in your arguments for why this particular ancient person would fall under NAGPRA, there is a tradition of, of oral histories from people. And it seems that that's a a different way of relating a history, as opposed to studying bones or coming up with DNA and matching it. And so I guess another version of what I was asking Ms. Fredin was, are there different ways to the same truth, or are we talking about different, different goals? In a sense, I think that there are different goals. I really do. I think that, you know, science, you know, our scientists always, you know, suggest that there maybe is a truth out there, and so they

advance different theories and they continually argue with each other over the interpretation and they seek to kind of debunk different theories. And I suppose if there's ever kind of an end result that then nobody contests, then in a sense that's a scientific proof of something, and then the larger community accepts that as a truth. Now what I find problematic in that way of thinking is that, from what I've seen in history, you know, they go through cycles and then, you know, 50 years later, nobody agrees that that was ever a truth and they're embarrassed that they ever thought of it and they think of something else that's pretty good for another hundred years or whatever and then that's the end of that. And I think with native people, I mean the way that I understand it, I mean, that the stories and the traditions have a certain consistency and relevance in contemporary life but throughout time. So they position people with respect to a certain land, a certain

geography, and a certain way of being on the land, so that they instruct sort of what, what the position is, and I do work in environmental policy and environmental ethics, and so it's more that type of knowing. So you could scientifically measure air pollution and you could decide how many pollutants or how many measures of pollutants could be in the air before it causes death, you know, to 0.2 percent. And then you have to decide whether 0.2 percent is good enough or maybe we should go up to 10 percent or, you know, what's that level of acceptable risk, right? But I think that with the way that native people know the, the world, I mean, there are just certain things that you shouldn't do and that that stays, you know, consistent throughout time and that's the relevance of that way of knowing yourself as a people. And so I don't think that the goals are the same. And I think that there's a lot of suspicion among other people that maybe the oral tradition isn't the truth. Well, it's the truth in the sense

that it serves the people in their life and in their world view. And, and it's, it's consistent in that, in that way. So I think, and I think that the statute was trying to take into account different ways of knowing the world. Now the other point that I'll make, and this is the political point, as I said in my talk, European-American law is the one that designates the moment of historic European discovery of America as being when the legal rights of European people kicked in, and native people are under that system. That's what's reflected in NAGPRA. And the way that I see it, Native American cultural items certainly that predate historic European contact are Native American. And that shouldn't be subject to some sort of genetic, you know, testing to see whether that's a truth. I mean that's a political fact, and this is the legal system that

came up with that structure. David Meltzer, you mentioned in your synopsis and I'm sure in your longer talk as well that you have no doubt that this particular person was Native American. Am I quoting you correctly there? Yes. And I guess this is a question for you and for Joseph Powell and for Anne Stone. This is, there aren't that many, as I understand, it there aren't that many remains as intact as this one of this age found in, in North America. Are there a lot? Are there a few? There are, there are a few. A few. Well, so what does one mean? What does studying one mean, and how much, I mean, how far out can you build theories off of one? That's a very good question. One, one is, is a part of a, a larger whole, and during the presentation that we gave, I pointed out that as a scientist, we have to think of these individuals first of all as human beings, which,

which they were, and to think of them in respectful terms, but also we have to think of them from a scientific standpoint as just one person from one place and one point in time. And it's part of, sort of think of it as part of a puzzle, so that you may have one piece here and one piece there, eventually as you gather more pieces of the puzzle, you have a much more clear picture of what's being represented. And that's the way that science works. That's always a difficult thing when you're dealing with a small number of individuals and it's the same thing that happens in the study of human evolution in other parts of the world and change in ancient populations. So I guess maybe this will be the totally naive question of the evening, but I'm thinking of, you know, people "why do you climb Mt. Everest? Because it's there" or "why did you settle the United States? It's our manifest destiny." Is science something like that, you have to pursue it because it's unanswered? You must pursue that? I think every scientist has a different opinion on that.

For me, it's, it's been a question of interest, simply because I'm interested in people and most importantly I'm interested in what's happened to us recently. For me, the big picture, the most important part of the question of our history and change that's happened, has not been what, what happened at the time of the end of the Pleistocene, it's much more important to know what happened after that. How did all these different people come to be? How did their languages and biology differ from one another? What was the impact of the rise of agriculture? All sorts of phenomenal things happened in the last 10,000 years that had a big impact on humanity. We don't really understand it well enough now, and we make, we're making more rapid and advanced kinds of changes to our society, our technology, and our biology, and we have no idea what we're doing. And so for me as a scientist, it's important to try to understand some of these things that have happened, some of the cultural changes that had, have had an impact. That's why these types of studies are important to me personally.

Other people may have very different reasons for... David Meltzer. I wanted you to answer the same question. I thought Joe was doing just fine. Thanks, Dave. You know, we're always going to want more, and I don't mean to say that in any sort of imperialist way, simply because fundamentally we're very curious. We, we want to know, we want to understand in, in a very real sense, we want to appreciate the shared human history, and Rebecca has referred to it as sort of the world heritage view, and I suppose I'm guilty in that respect, because I don't draw racial distinctions today. I don't draw them in the past. What I'm trying to understand is what is it about us that makes us fundamentally human and what are, what are the achievements of us as a species, as a people, all people.

So I also, having said that, recognize that I could see how people would say "Enough is enough". I'm certainly, as an archaeologist, and particularly as one who's spent a fair amount of time in the 19th century, I can tell you that our, our record is not stellar, and some of the things that have passed as archaeology in the past are, are really just genteel grave robbing. And so I well appreciate and well understand the perspective that native peoples have on these remains to say What else do you need? And why else do you need it? So I think a rapprochement, a dialogue, if something like that comes out of the Kennewick business and perhaps that might be the most productive thing that comes out of the Kennewick business, is it has raised issues and put them in stark highlights that weren't

highlighted quite as well before. And if, if it in fact encourages a much greater respect and awareness on both sides, then I think that would be very positive. Adeline Fredin, what do you want to know about your people's past that scientists could help you answer? There's so much we want to learn about ourselves. You know I think that just right now we're beginning to get pretty much involved in that field. I'm pretty sure as time goes on that there will be a better way to study without the kind of science that they're talking about right now, the invasive science or the destructive science.

It's something that we just can't think about, but I'm pretty sure that it was, in time to come, with the kind of technology that is coming down the road, it may not be a problem in the future. We need to know as much as we can. It stands to serve not only the Native Americans but the environment or health of the country. There is so much that the Indian people themselves have forgotten over time. Or maybe that they still remember and because the way science treats Native American peoples' information, that they are not willing to share the information. I'm pretty sure that maybe over time that science will begin to appreciate

what the Indian people know about their environment and their world, and maybe we can work together. But there is a present setting that we have right now that I can't get into, on the advice of my attorney. It just puts so much at risk. It just puts so much at risk. This is so interesting, this particular case, because it's not only a question of science but it is a legal question that's a question that's in the courts right now, and so I know there are a lot of things you can't say and people who didn't participate because they are party to a lawsuit. One of the questions I had about the current pending lawsuit in general was what it might mean, Rebecca Tsosie, for NAGPRA, if, if the scientists win. Well, I mean, there there are different ways that I guess they would perceive themselves as winning.

There are many, many different claims in that case. There are constitutional claims and there are statutory claims. Certainly, you know, one of the claims that they seek to prevail on is the determination that this set of ancient remains is not a Native American and so only scientific testing can establish one's identity as Native American, and that we would just sample contemporary people who are now removed from nine thousand years. In which case we should sample the whole world and find out that nobody is related to anybody and therefore, you know, what does that tell us? I mean, so everybody's going to be a loser if that's the end of the claim. I mean, I just, I, I think that would be ludicrous. Now, assuming that that isn't what happens, and the question is how do we interpret cultural affiliation, I mean those are all going to be precedents. I mean obviously this is at a preliminary level and so it's not going to be binding on many courts. But, you know, one can see the world in which the

interpretation of the statute certainly moves in another direction. So I would say that in the law again, everything is subject to interpretation. And we've got to make sure that sort of the normative, you know, framework for that interpretation is one that's equitable, and one that's just, and one that doesn't just seek to perpetuate some sort of a, you know, world view of a particular group. And that's certainly what I would be most concerned about. Well, given what Adeline Fredin was saying about working together and dialogue continuing, is it, if these remains are returned to one of the five groups that are one of the five Native tribes that have a claim to them or have put their names in, does that mean that there that they cannot be studied by scientists? My position is that the statute says that rights of control and disposition over Native

American cultural items are located in the tribes that are affiliated to that. And in this case, my understanding is it's a joint claim among a coalition of tribes that shared a common, you know, area and way of knowing their ancestors. And certainly those tribes would have the authority to, you know, permit certain testing or to deny certain testing. I mean that's what the legal right describes. And to the extent that scientists make a legitimate claim for certain types of testing that are not, you know, culturally impermissible, then, you know, I know several tribes that have actually agreed to certain things and what Adeline is saying about the science and native people, you know, working together, I mean we have tremendous issues, environmental issues and health issues, that we rely on scientists, and we're very, you know, fortunate to have that expertise, and some of our own native people are being trained as scientists. So we're not, you know, a group of science haters and to

jeopardize, you know, all of the good things that are happening over essentially a very imperialistic claim about race and culture that it seems to me doesn't even have a foundation in the science that they seek to root it in, it seems to me that that's very, very short-sighted. One of the things that you mentioned was "Native American by statutory definition", and I know these are the legal terms for things, but that's just struck me as a really odd way to define somebody, by statutory definition. And I know, Joseph Powell, in, in the report that you wrote many months ago, and I'm not going to ask you to quote it verbatim, within these, these very narrow parameters, you didn't feel you could place it anywhere, this particular person. And it's the analysis that we were asked to do was making a presumption that categories, social or real whatever, however you want to view races,

those kinds of biological or social categories existed ten thousand years ago. That is, is an assumption. It may be a real one but, but it may not be. If those groupings didn't exist in the past, it's not unreasonable to find that this, this person doesn't fit in anywhere. The analogy is to for someone to take out of the color spectrum just red, the primary colors, red, yellow, and blue, and then present you with a white sheet of paper and say which one does it belong to? So there's, there's the the law, the words of the law. There's the way that scientists view the world. There's the way that the tribes are viewing this. We get back to that notion of truth and who gets to define it. I think that, if I might... Oh go on. I think we're at the nub of the issue right here and a lot of this has been said about conflicts between science and

religion or science and culture. But there's another, a third point on this and it's science, religion, and law. That's the third necessary point here. Joe has talked a lot about whether this is Native American in a racial, you know, in a racial category. But I'd like to make the distinction between the way that you've talked about race, which is the scientific meaning of that term, and the statutory meaning, because the statutory meaning is "of or related to a group of people indigenous to the United States", period. That's what it means in the law. And there's a difference there. The way that biologists talk about it and basically dismiss the meaning of the term is the way we all think of race. You know, we have a cognitive meaning of race. And when you read the law, you have to look at the definition in the law. If these remains are Native American by the

statutory definition, this law applies. That means tribes by some mechanism will have rights to, to the disposition of those objects. Now, a couple things I guess. To again place it in a little broader context, you have to remember that this case, these two lawsuits, Bonnichs plaintiffs and the Asatru plaintiffs, these are not the typical cases. There have been lots of other cases, where almost, you know, 18,000 human remains in collections, quite a number on federal land and excavations that have gone just great. There's been good science done with them. The tribes have all been happy. They've got the stuff. This is the anomaly, this case is. It's balancing the issue between scientific curiosity and is this an

interesting situation? You bet. Lots of people are interested, but it's balancing it against the rights of people to make decisions regarding what the disposition is and who has precedence here. Someone asked me a question a little bit ago about, well, some people think that science should get these remains. Who's that? Who is science that will be accepting these remains? There's no institution there. Someone has to have control. If these individuals or these remains are identified as being Native American, well then, we'll go through the hierarchy and figure out which tribe has control. If they're not, if they're not Native American, the United States retains control, the federal agency retains control, and most federal agencies when they have remains that are not Native American, they do one thing. They will study them, and generally they will rebury them somewhere. That's the common

pattern. So the important thing to look at here, or actually two things, one is this issue of information and collection of information. And many people are interested in that, and good science is being done on these. But the other question is, So what's going to happen after that? What's the disposition after that? And there's some question about, well science should keep them. That's not the common pattern. That's not what we do with Euro-American human remains or African-American human remains or Hispanic human remains. That's not what we do in this country. So that's the issue. Lastly, when I define this triad, you have to consider that science is a process. You're continually gathering information, testing hypotheses, going and get more information, testing it again. It never ends. It's a process that goes on and on forever. Law doesn't work that

way. Law, you bring everybody in the room and you present all the information, this court aside, I think, get all the information in there, and you get a decision, and you can appeal it, you can appeal it up to the Supreme Court. But ultimately it's over. It's done. It's precedent, but it's a done deal. Science doesn't work that way, and that's the real rub here. I cautioned everybody when I talked last night, never to mix the two sections of the law: the excavation and discovery provisions, and the collection provisions. I'm straying across over now to talk a little bit about the collection side. It does not apply to this case but it provides something that is illustrative. There's a section in the statute for collections that says if a tribe comes forward and they have standing and there's an object, remains, that they're claiming that fit a category and they can show cultural affiliation, or a lineal descendant

comes forward that can show that they're a lineal descendant, the institution, the museum, the federal agency must repatriate it to them - notice I use the R word - repatriate it to them, except if it is necessary for the completion of a specific study of major benefit to the United States. What's that mean? Well, I don't know. But there's a couple things that I can posit. One is, that decision has to be made by the United States. So it's not just a scientist making the decision, it's the United States, and one would assume that it would probably be the Secretary of the Interior. because he has responsibility for this law. And secondly, it has to be a benefit of such importance that it would not, it would forbid Adeline from repatriating the remains of her great grandmother.

She would not be allowed to repatriate those remains because they were necessary for completion of the study of major benefit to the United States. That's a pretty high standard. And in the common law and in general practice, what fits that? What other examples do we have of that? Criminal investigation. Probably national health, if the individual's remains had some disease. One, I guess, could think of maybe national security, perhaps, but that's about it. Is that a major benefit? Yeah, that's pretty major. So it's a very, very high standard. And the important thing to realize is this rub between science and religion and law, we're not refighting this right now. Congress already did it. They did it in 1990. They passed the law by unanimous consent of both houses, and it was signed into law by George Bush.

So part of this is kind of moot, except for this case. But the magistrate has to operate, unless he declares it unconstitutional, which I guess we could see, but he has to operate within the boundaries of the law. I want to open the floor to questions right now. There are, again I remind you, four microphones. We'll try and take as many as we can. Please be concise. Isn't it just as likely that the Kennewick Man is related to Chinese- Americans as it is to Native Americans? And in that event, who really has a greater genetic claim on this? It seems spurious to make a cultural claim. There may have been no descendants of the Kennewick Man. That really seems to me to be so far afield from anything that one can imagine at this point. This guy would lived eleven thousand years ago. He doesn't have any connection

to current cultures. And in the end if it's, if it's found that there's a greater connection between Chinese-Americans and the Kennewick Man than between Native Americans and the Kennewick Man, isn't this an incredible opportunity to understand on a worldwide basis the genes and genetics of that? And this gentleman here just said, well you know, what could be so important about it? The genes of this individual may teach so many different things about how pathways have changed, how medicines may be used, how different things happen, to constitute I think a very important national endowment, not something that should be relegated to a group of people that seem to have a cultural claim that can't be substantiated. It should be a natural treasure. And I would like to open it up to anyone. I understand that there are some legal issues about the geographies in which these remains were found, but I don't see that the connection's been made to

a tribe as opposed to a Chinese-American. And if that connection isn't made genetically, where is the claim that this represents something about this culture? I don't understand it. I think that genetics isn't particularly going to be informative. I think it's pretty obvious that this individual is Native American, and you don't need genes to tell you that. I can tell you I have been privileged to work with an individual who was found in our glass case, and he lived about eight, eight thousand years ago. I did a DNA study after consultation, and we found that the type of DNA that this individual had is very common today in Native Americans.

So I think that relationship is pretty clear actually. So I, I, I don't think that genes are the answer to this particular question. The gentleman in the green shirt back there. It seems to me that we're trying to solve something here that is really the question of "how do we know what is truth?" Well, if we take a religious approach, it, but, it is often based upon belief. Belief, culture, is a culture-based kind of thing, at least for many people. And what we know is what we have learned through others. Or we can look at it from the standpoint of law, which finds truth by argument, by precedents, and by trial within a legal system, and the legal system differs across cultures. Or we can look at it through

science, which proceeds by approximations of successive steps through trial and confirmation or denial, never coming to a final answer. So if we look at it, if we would look at it those ways, I would be interested in having the group comment. Well, I guess I would just like to make one point. You know, I wouldn't say exactly that science is in search of truth with a capital T. We want to, or science usually works by measuring things making hypotheses and figuring out how things work. And then people make decisions on how to use that information. And those are legal or ethical decisions. And science, when we practice it, we are supposed to be without biases. But we're human and so obviously bias comes in.

And so science is not entirely separate from the ethical and the legal, and those issues are very important and have to be taken into account. Simply, add that science is a learning strategy. It's a way of understanding your world and of reducing your ignorance, worrying away your ignorance. Science is a very vibrant thing. It's, it's alive, it moves. I know it's frustrating to peoples on the outside looking in, saying, "well, how come you folks can't come up with an answer, and how come the answer you gave me this week is different than the one you gave last week?" And I think that's a testimony to the fact that we are learning something. We are worrying away our ignorance. We are making progress. But I would certainly second Anne's comment about truth.

I certainly don't have, well, I mean it's really easy when I have the microphone to tell you I'm telling you the truth but I don't have a monopoly on it. I don't even necessarily understand what it is. But I also understand that the approach that I take, my effort to worry away ignorance and to try and learn is in some ways kind of different from the approach, the legal approach certainly, and perhaps different from the, the kinds of approaches to history that you would get from Native history. And that's not to say that the scientific approach is privileged. I view it as a different approach, is all. I just have a very quick response, and one thing that I was very impressed with in today's presentations, I actually learned a lot from the scientists here and I thought that they all did a really fine job of kind of illustrating, you know, the way that different theories worked and the way that you could interpret the evidence in different ways to suggest different things. And that seemed to me a very balanced and rational

approach. When science and the law intersect, what happens sometimes, and this is a big topic of discussion obviously if you get scientific evidence at trial, you know, the average lay jury, they don't know anything but they do know that it's science and so they tend to say well, you know, it just shows he did it, you know, and they sort of go to the bottom line, yeah he's guilty, science says he's guilty. And that's what we in the law worry about because the scientists do know the way that their institution, the process works, but oftentimes people that aren't trained in that methodology misinterpret it and they come up with a bottom line. Genes suggest, you know, he's Asian. Well, you know, it seems to me that, that's not what science is saying, but the interpretation among people that don't know the science tends to be something else. And to the extent that we make decisions under the law on that basis, I think that's very, very problematic. Thank you. This woman down here. Thank you.

In the event that there is further scientific research, what chemical analyses other than radiocarbon dating and DNA examination would you consider to be valuable to our body of knowledge? Well, there are any number of chemical and isotopic tests that can be performed on human remains. All of these require destruction of the bone. It's sort of equivalent to having a biopsy done or to removing tissues of any kind. So it requires destruction of the bone, which in my dealings with tribal representatives in my home state and other places, is virtually, is very consistently considered to be inappropriate by members of tribes. So it requires some consultation, it requires discussion, and require, requires what Ms. Fredin pointed out of a dialogue and just asking for permission. If permission were to be

granted, there are a number of studies that might tell us something about the kinds of food, excuse me, the kinds of foods that this individual ate based on trace elements and isotopes that are present in the bone. There are some studies that might clarify what the red pigment or red staining that, that seem to be present on some elements, whether that's real or not, whether that's due to simply the soil that surrounded his body. But again it's, you know, it's a matter of scientists talking to tribal representatives, talking to everyone who's involved, to find out what's important, not only to the scientists, but what's important to the tribes as well, at least from my perspective that would be the way to approach it. But there are other things that could be between. This gentleman down here, you. [inaudible] questions that I think can be answered pretty quickly. Mr. Powell, I think this afternoon I heard you say that the gravesite you felt, or that

the panel that you were on earlier this year thought, the grave site was a prepared site and inferences could be made from that this, the remains were buried by somebody. Possibly. OK. I've seen nothing in the record here over the last three years that studied the site and the history of the site, which is, to wit, it's a major floodplain and has been for thousands of years, and I'm wondering how that might square with the floods that have taken place along this part of river. Well, I'm not a geomorphologist, so I can't say much about the geological context. There were a team of two geomorphologists on there. To be honest with you, I glanced at their part of the report, which I got to see on Friday with the rest of the world, and like everyone's eyes did on my part of the report, they glazed over, I went to the next part, and I still have to go back through it, to be honest with you. Our, the two physical anthropologists who examined

the remains, simply did what we do with any other set of remains out of archaeological context. In other words, we don't know what was going on with this set of human remains. They were recovered on a shoreline at a couple of different episodes of collection. We have nothing other than the remains themselves. Based on that, we've then try to compare that set of remains to what we know of individuals who have died under known context. People who have been intentionally buried without the protection of a casket or other container. Individuals who have died right here on the Northwest coast and whose remains have fallen into bodies of water and recovered in the water. The individuals whose remains had been in water, been washed ashore. Individuals whose bodies were used for consumption by different kinds of animals and insects. All that information we have in large databases from forensic case work and we simply compared the remains of of Kennewick and came up with a probability statement of which set, which set of

contexts he was most similar. And the highest probability, although it wasn't a hundred percent, was with individuals who had been intentionally buried. Does that mean he actually was? Well, no, there's still, still a chance that he was not, that he could have been covered in different geological context. We will actually never know, simply because we don't know what the primary archaeological context for those remains was. [inaudible] That the Native people's legal viewpoint of NAGPRA, of the way that they read NAGPRA is that all remains prior to colonization contact from the European continent are Native American remains, is that, am I, did I hear that correctly? And I'm wondering what the other panelists might have to say about that. That's, that's my interpretation of the statutory language, which indicates that Native American cultural items are items that were indigenous to the Americas, meaning certainly that

before the historic contact of European people, I think, that, you know, by definition, those are the native people of this land as they existed in that time. And so I was making the point that contemporary tribes for the most part believe that they are related to the ancient people of this land, that they share the land because they share that identity as indigenous people of the land. That doesn't have any relation to this idea of genetically proving that that link and that, you know, European claims, you know, stem from contact, the historic contact, and that's indeed the dichotomy that's been drawn in other countries such as Australia. If I might just add that the Department of the Interior in a letter to the Army Corps of Engineers specified that their interpretation, that our interpretation of the definition of Native American was "of or related to a group of people that resided within the United States prior to the documented arrival of European colonists". This is a question directed at Mr., Mrs or Miss or

Ms. Tsosie, is it Tsosie? That's me. OK. OK, the question is if a 6-foot 4-inch long, long narrow-skulled Viking was found in the banks of the Hudson River, would that be turned over to the Mohawks? I don't understand that question. I'm talking about Native American people, ancestral people of Native American people today. You're stipulating to a situation, my students do this all the time, well, what if we know for a fact that this person is a Viking? I'm not talking about Vikings, I'm talking about Native American people, and from what I hear today, this individual here is Native American. I am not addressing hypothetical situations in which the Martian from the moon is found...No, we're talking about people that were here in Newfoundland and we're talking about Mystery Hill in New Hampshire. We're talking about the Mandan Indians who were, who are blond-haired, blue-eyed in South Dakota.

We're talking about my tribe, the Citica tribe, which was in ancient Nevada and we were slaughtered, exterminated by the Paiute Indians. You can...Do you have a question? This guy up here has a chance. He has more standing, he has more privilege, because he's so-called Native American or whatever. I am a, I am a Citica tribe member. If you read Sarah Winnemucca Hopkins's book, Life among the Paiutes, she talks about the extermination of red-haired people. Sir, if you have a question, you can ask it. That's the statement. OK. This has been a white-bashing hate fest. Understand? I've never been accused of being a white basher, and this is really... My students have called me many things, that's not one of them. It is in fact the case, based on archaeological evidence, that Vikings did - nobody

get nervous, I'm not going to go off the deep end here - that the Norse did in fact make it to Newfoundland. Around 1000 A.D. Leif Erikson, Eric the Red, and Leif's brother was killed here by the Batok peoples. The Norse had clearly extended beyond their supply lines. They were in a foreign land that they were attempting to colonize, and they failed, and they beat tracks back to the other side of the Atlantic. We in fact use that landing as a wonderful example of a failed migration. They got here, they tried to establish a toehold, and they failed, and they turned around and went back. So I don't want anybody to go away confused about the nature of the archaeological situation. There was a contact around 1000 A.D. It was extraordinarily brief. It had virtually no impact on the rest of the continent. They did not wander to Minnesota. They did not wander to New

Hampshire. Lord knows they didn't end up in Tucson either. So I think it's important to note that indeed for one brief instant, archaeologically speaking, the Norse were in fact here, but it had virtually no impact whatsoever. The site, by the way if you're interested, is called Lance-aux- Meadows, and it was excavated in the 1960s and in the 1970s and there's a wonderful volume out on the site, which in fact shows quite clearly that we have Norse artifacts here, we have boat sheds, we have houses, and all that sort of thing, but that's it, no more. My question was, if there hadn't been a controversy and all the press on Kennewick Man, would we have ever even heard of him and how significant is this toward our understanding of Paleoindians? I think that this individual would have received a lot of attention despite or without the controversy. The individual

found in our glass case certainly taught us a lot. And then he was reburied. So I think in that case, the consultation process and the process I would say worked for, for everyone. We had the opportunity to learn a lot, and he was reinterred with respect. Certainly other ancient remains that I've had an opportunity to, to examine, each one adds to our knowledge base and certainly each one is important from a scientific standpoint, and again cooperative efforts are extremely important as well. I happened, as I said during the question and answer session this morning, I had the opportunity to examine two ancient remains that were at least eight thousand years old from the state of Minnesota prior to their repatriation and reinterment. And that was done in conjunction with and in consultation with members of the Minnesota Indian Affairs

Council, who were there present during the analysis and study. So I think that, that certainly this would have, as Anne said, received attention without the controversy. How the process of scientific investigation would have proceeded may have been very different. And so that's, that's another question altogether, as to what kind of science would have happened, if any. And I'm not sure, we can play as many what if games as we want to. But certainly this particular case has turned out in one way and it's proceeded differently than other ancient remains that I've had the opportunity to be involved with. My question, over the last two days, I've been here and learned a lot about the controversy behind it Kennewick Man and all the different people that are fighting for him and control of him. And my question just kind of goes beyond the controversy and asks what

has Kennewick meant to each of you and to the fields you are in? What, I mean, what do you see as the importance of Kennewick Man, beyond just the fight for him? Can I try that first? That's, that's a very good question. What is importance? He has for me importance on a number of different levels. One is that, I think first and foremost, is that he was a human being and he has, if he's told us nothing else, to remind us that all peoples of the past had lives just like, like each of us here and concerns and they had arguments and they might have been involved in Kennewick panels, had they had similar kinds of issues to deal with, who knows? But certainly they were human beings and we have to remember that and treat them with respect. The second thing is that from a scientific standpoint, he has significance because he's one of a

growing number of ancient human remains found in North and South America. They give us a snapshot of what life was like at that time period. And as Dr. Meltzer has pointed out, we're now starting to see the dovetail, even though we didn't talk about our talks beforehand, we're starting to see that all our lines of evidence are converging in many ways. That's one or a couple of sets of opinions. Not everyone would agree with the way we're interpreting things. The third level of importance for Kennewick is that of course he has become the test case for a piece of federal legislation. It is a piece of federal legislation that in my opinion can work and has worked, because in my own home state, I do consultation with tribes and we do projects do scientific research in consultation with native peoples with their permission, and ask the questions that they're interested in as well as the ones that we are. So he does have a number of different levels of importance. First and foremost I want everyone to remember that he tells us about his humanity. And I think for Native people it is a very important, you know, moment and

a couple of the members of the audience have said, you know, this is somewhere almost at the, you know, turning point of the century, the millennium, and, you know, it's a time to assess what, have we learned anything from the past history, you know, all of these years of a certain way of being, have we learned anything and if this panel is representative of what we've learned, then we've learned to talk to each other for one thing and hopefully we've learned to respect each other. And I think that that's what the statute was intended to do. And hopefully that's the way it will be interpreted in the courts. And I think, from the perspective of a federal official, I think this particular piece of litigation has provided two things. One is sort of this matched set of decisions, one which has been deemed arbitrary and capricious and remanded back, and the other one which appears to have been OK, and that's a useful thing to see in any piece of law. But you have two things that happened at about the

same time, and one is OK and one is not. And it's important to look at the differences between those two. And the second one is, although there is no time limit for the federal officials to make their decisions within the statute, the magistrate in this case has definitely said that things need to happen in a timely fashion. So that's a useful thing to remind, not just the Corps of Engineers in this case or the Department of the Interior in this case, but all federal agencies when they have human remains that they discover on their lands, that they need to act in an expeditious fashion. And I just wanted to ask what anybody might view about what the intent or what the original 8 scientists that filed this lawsuit were trying to accomplish by filing a lawsuit. Anybody want to answer that? None of them are, is here. So, well, I'll address that because one of those scientists was my graduate advisor and we're on the phone all the time, about lots of different issues, primarily research

related. I think, and I can't speak, I'm not, I don't want to put words in their mouths, I can only speak from my contact with Dr. Gentry Steele, who is one of the plaintiffs, that they were simply interested in having the opportunity to ask the same kinds of questions that I had a chance to as part of the government research team. Who was this person? What was his life like? The things that scientists often ask of ancient remains. And I use the term "ask" when we talk about the analysis of human skeletons because, in my opinion, those human beings have something to tell us that that we can act as, as scientific interpreters. That does not mean that's the only story they have and it's not the only meaning that they have for different groups of people, but from one standpoint they do have something to say. And my guess is that the people involved in this case are wanting the chance to ask those questions and maybe have some answers for themselves.

I think for this people sitting in here, they need to understand that our traditional values, our traditional teachings that we have a great deal of reverence and respect for our people in our way who've gone home before us. And my concern or confusion, I've been listening about this for the past year or two and I s-, I can't help but feel that this is a desecration of the remains of one of our ancestors under the guise of scientific research. I think that our people and as I was taught and spoken to, that's all we want, is an opportunity to rebury the remains of our ancestors so that they can continue their journey. The Burke Museum lecture series has provided us a glimpse of the emotional debate between the rights of science and religion. So what's next? A federal

judge has given the Department of Interior until this fall to decide whether it will let researchers study the remains. Thanks for joining us for Kennewick Man on Trial. Good night. If you would like to learn more about Kennewick Man, KWSU media is offering a two-tape video set of the complete lecture series that took place at the Burke Museum in Seattle during October 1999.

The set includes all six speakers' presentations, unedited, in their entirety. To order your set, call 1-800-883-0124. The cost is $39.95 plus shipping and handling.

- Program

- Kennewick Man On Trial

- Producing Organization

- Northwest Public Television

- Contributing Organization

- Northwest Public Broadcasting (Pullman, Washington)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip/296-720cg5dp

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip/296-720cg5dp).

- Description

- Program Description

- This documentary features edited coverage of the "Kennewick Man On Trial" lecture series and panel discussion that took place during October 1999 at the Burke Museum. The event was held to express conflicting concerns between Native American tribal communities and scientific interests about a 9000-year old skull recently discovered in Washington State, commonly referred to as the Kennewick Man. The program opens with Stacy Hall providing background about the controversy, with opinions of Armand Minthorn, Doc Hastings, and Francis McManamon.

- Copyright Date

- 2000-00-00

- Asset type

- Program

- Genres

- Documentary

- Topics

- Social Issues

- Race and Ethnicity

- Rights

- (c) 2000 Washington State University Board of Regents

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 01:27:26

- Credits

-

-

Associate Producer: Rowlands, Wendi

Composer: Mysers, Dan

Director: Marcelo, Marvin

Editor: Waiting, Chris

Executive Producer: Wright, Warren

Host: Hall, Stacy

Moderator: Sillman, Marcia

Panelist: Fredin, Adeline

Panelist: McKeown, Timothy

Panelist: Meltzer, David

Panelist: Tsosie, Rebecca

Panelist: Powell, Joseph

Panelist: Stone, Anne

Producer: Curry, Robert

Producer: Hall, Stacy

Producing Organization: Northwest Public Television

Writer: Hall, Stacy

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

KWSU/KTNW (Northwest Public Television)

Identifier: 3543 (Northwest Public Television)

Format: DVCPRO

Generation: Copy

Duration: 01:34:00?

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “Kennewick Man On Trial,” 2000-00-00, Northwest Public Broadcasting, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed December 15, 2025, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-296-720cg5dp.

- MLA: “Kennewick Man On Trial.” 2000-00-00. Northwest Public Broadcasting, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. December 15, 2025. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-296-720cg5dp>.

- APA: Kennewick Man On Trial. Boston, MA: Northwest Public Broadcasting, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-296-720cg5dp