Louisiana Legends; Dr. Michael DeBakey, Part 2

- Transcript

Funding for the production of Legends is provided in part by the Friends of LPB. There are no such things as incurables. There are only things for which man

has not found a cure. My guest is the preeminent surgeon of our times, Dr. Michael DeBakey, a native of Lake Charles, Louisiana. And, Doctor, you perhaps recognize that quote comes from one of the more than twelve hundred scholarly papers that you have written. Do you believe that? Is that your own feeling? Yes, you see, what is incurable today and this will become curable tomorrow. We have problems for which we have no solutions now. But once we have a solution, it no longer is a problem. And as our knowledge accumulates through research and the development of new knowledge, these problems will have solutions found for them. Doctor, will a cure for cancer

be found in our time? Oh, I don't think there's any question. Well, now you're asking me when. Yes, sir. You never can predict when new knowledge is going to be developed in any area, whatever it is. Someone may develop a profound theory that then will attract brilliant minds to work on it. As soon as that happens, then you have many more chances that that theory will become the useful, realistic theory in terms of developing your knowledge or it will fall by the wayside and quickly be determined because you get so many people working on it. And it also opened ups, opens up new avenues of approach to whatever this may lead to. And that's how research evolves and in a sense, in a sense,

expands the mind. So you believe that cancer, we will find... I don't think there's any question about it. If you look back, you see, sometimes it's good to look back historically to have a better perspective of what may happen in the future, even though you can't predict it. But if you look back historically in the past, you will see that we were at different stages in the past when certain diseases were considered impenetrable, they were considered mysterious and we couldn't find the cause. We couldn't find the treatment. One of the ones in recent history was polio myelitis, you know, and there were all kinds of theories about its cause and everything. and everything else of that kind, you see, lots of mystery. Well, as soon as the specific cause was found, a specific virus scientists went to work on developing a vaccine and the solution

was found. Every disease in the past which we now have a solution and a means of either prevention or effective treatment, at one time was a mysterious disease. Am I putting you on the spot by asking: Do you believe that cancer might be a virus? Do you have any personal theories that you've evolved? Well, I think there's a very good chance that certain forms of cancer are due to viruses and I think a good many so-called cancer scientists believe that. Doctor, do you still engage in much research? Yes, we have a fairly extensive research laboratory. Our research largely focuses upon the cardiovascular system - Yes, sir. - and trying to have a better understanding of certain aspects of that system and having a better understanding of the disease arteriosclerosis, which really accounts for

perhaps 80 percent of all of the patients we see with cardiovascular disease today. Doctor, how many surgeons have you trained thus far in your career? Well, at the last count, which was made several years ago when these men organized themselves into a society of their own, there were close to 500. Goodness sakes. So since then I've trained more. In the second generation? Oh, yes, some of these people now have their own training programs and have trained other surgeons. Yes, younger surgeons, sure, in other words. You see that's the sort of immortality you have -- Yes, passing on -- passing it on. That's right. I gather you felt that way about Dr. Ochsner? Oh, yes, I should say. Doctor, what do you look for in a young student? What says to you that a man has the potential to be a surgeon, a good one?

Well, I would say first and foremost is a certain amount of general intellectual ability. Secondly, that he has absolute integrity. This is one of the most important traits in a physician or surgeon. A doctor's got to have absolute integrity. Thirdly, he's got to be disciplined and have self-discipline. This is a very important aspect here because without it you, you don't have the motivation, in a sense, you haven't got the capability of motivating yourself to work hard, you see, to learn as much as you can. And finally industry, which is a part of that. Doctor, does surgical success exhilarate you and do losses on the operating table depress you? Oh, yes, no question about it. You know, there's a book entitled in recent years,

entitled The Agony and the Ecstasy. Yes. I think it expresses as succinctly as I can think of, of the emotions that we experience. We experience a lot more ecstasy than agony, but every time we have a death, we experience that agony. How do you handle that side of life which with which you must live, the agony of it? Well I try to work. I try to.. to try... I try to get at some things that need to be done and sort of divert my mind from it, but I don't think anything... I don't think there's anything that can be done to heal that except time and, you know, working helps you, alleviates you to some extent. It's, it's, it's a help, in the

relieving the intensity of it, you see. Doctor, how does a great surgeon keep a sense of balance? By that I mean wouldn't it be rather simple for a man to suddenly begin to feel godlike? These people day in and day out come before him in supplication, in desperate need and perhaps he alone has the gift, the art, the talent to give them this most precious possession: life? How does he keep a sense of balance?How does he or does he? Does he say: I'm a mortal, too? Well, I don't think so. I think that. I don't know. When you talk about greatness, I'm not relating that to myself, but most of the people that I have known and I have admired greatly for their talents capabilities and so on are people with humility. And I think the greater a person is in terms of his accomplishments or his talents, whatever they may be, in the arts,

in science or whatever, become increasingly humble, because they increasingly recognize with their talents and with the knowledge that they have accumulated, how insignificant we are in this universe as a human being. And how little we are here, how short a time we're here. Years are going by and have gone by and will continue to go by. Now as far as a doctor's concerned, I think his humility comes from the fact that he's unable to accomplish all the things he'd like to do. And he sees patients that he can do nothing about and he recognizes his helplessness, his inability to help them, his

inability to get them over their condition, his inability to restore them to normal. To me that's very humbling and I think every doctor feels it. How often does the unexpected occur at the operating table? In other words, can you still be surprised with all of your experience? Yes, but that occurs now with, with almost a rarity because we have such precise methods now for diagnosis. Before we go to the operating room, we know almost exactly what we're going to find. We, we can predict with great accuracy what the situation's going to be. But there are a certain proportion, small as it may be, that occurs from time to time. What sets one surgeon from another? For example, a group of surgeons have the same information available to them, the same diagnostic equipment, and so on. What

would make one man a better surgeon than the others, given that same information going in? In other words, what would set a man apart in that particular art? Well, I think it's no different there than it is in other fields. What sets one writer? I mean most writers can write pretty well. Yes. But you, you know, you come along with a Tom Hardy only occassionally. Yes. See set apart. Same way in music and art and painting, you see. What sets him apart from the others? And I think it's a, it's a combination of talent and that special intellectual organizational capability that some people have, are born with perhaps and then develop better than others.

Doctor, a two-part question: What is the future of heart surgery and specifically how long are we going to live? A child born in 1982, a normal healthy child, what should his life expectancy be? Well I, I think the life expectancy, you know, has, has steadily increased. Today, it's in the neighborhood of, I think, 79, 79 or 80 for women, for females, and about 73 or something like that for men. I think it's going to continue to do that, perhaps slowly, progressively, but steadily and maybe in our lifetime, we'll see a life expectancy of 100 years. 100 years, years would not be uncommon? No, not at all, and I think over a period of time it'll go beyond that. There's no reason why

it shouldn't. Now we're beginning now to start some better understanding of the aging process. See, once you start to understand that, you may find ways to delay it, to slow it down, you see. And I'm sure, I'm sure that's going to happen. We may not be able to eliminate it so people can live indefinitely, but we've already done it to some extent. We've got people today who are, you know, working quite actively when they're 70, 75 or in their 80s. But we're learning more about it. We have a research institute in Washington called the National Institutes of Health Institue on Aging. That's a new development.

And I think more attention is being paid to that now understanding of it. So there isn't any question, we're going to do that. As far as heart surgery is concerned, as far as its future, it'll continue to be a very, have a very active place, perhaps expand somewhat. But what you can't predict is what will happen if, if some new knowledge develops that will eliminate certain diseases for which surgery is essential in the treatment now. For example, you take what we call arteriosclerosis, atherosclerosis, referred to as hardening of the arteries. If we learn the real cause of atherosclerosis, and we can then develop a means of preventing it or treating it by some medical means that

eliminates the blockage of the arteries, we will have removed surgery as a means of dealing with it effectively. And in, you know, many forms of this disease surgery is the only effective way to deal with it, to restore circulation to overcome the blockage, you see. Or in the case of where the wall of the artery weakens, called aneurysm, to remove that and replace it with an artificial artery. Now if we learned the true cause or causes -- there may be more than one -- and can then apply that knowledge in a preventive way or a curative way other than surgery, then cardiovascular surgery will be, to some extent, curtailed. I myself don't see that happening in the near future so

I believe that there will be a greater expansion in cardiovascular surgery. Not a rapid one, but progressive one. Doctor, is there a loneliness attached to being at the top of a great medical institution? By that, I mean this. When problems arise, troubles come, everyone knows that Michael DeBakey is there to turn to. But my question is: Who does Michael DeBakey turn to when those problems are...Oh yeah, you know, the buck stops here. Yes. What does a man at the, at the pinnacle do? Well I think he...It must be very uncomfortable not to know anybody who knows more than you in your profession. It would drive me crazy. You know the most wonderful thing to be able to pick up the phone and call someone else. Oh, I don't hesitate to do that. I don't hesitate to do that. There are many problems that I think others know more about that I do. You know, even in cardiovascular surgery, I don't feel I know the whole field that

well. There are some things I think I know better than anybody else, but I wouldn't hesitate to call other doctors in consultation to see patients of mine. And I do that all time...cardiologists, I have respiratory specialists, nephrologists, kidney specialists, neurologists. So they're there. I call them in to see my patients. How wonderful that must feel to a doctor for Michael DeBakey to call him in for counsel. Sure. I would think that I would rush out and ask for a raise, Dr. DeBakey. Doctor, if you're going to perform delicate surgery on someone, would you rather know them or that they be a stranger to you? No, I want to know them. I like to know my patients. In other words, I like to talk to them. I like to brief them as much as I can about what they have. In other words, I try to get them to understand as much as they

can what I'm trying to do. But what can be done for it with the future and so on to get their cooperation and they're in a sense reassurance, you see. In fact, it's for this reason that I wrote a book called The Living Heart which is written for the, the average layperson so that they can understand more about the heart and blood vessels, and how it works and what can be done about it, what conditions can be helped, how you can perhaps keep your heart as healthy as you can. I think it's important, in other words, for the public to understand and I do everything I can to educate the public so I when I'm dealing with my patients, I do that with them and the families. I do want to know them and try to relate to them. I think it's easier then to relate to them to get their confidence.

Fantasize with me for a moment, if you would. If you had not become a surgeon, what other field of endeavor might you have gone into? What out on the periphery might have captured your attention or your intellect? Well, I think I would have gone into some scientific field. I was early interested in science and in mathematics. And I might have gone into some field like physics or some other scientific field. I was interested in that very much. Perhaps research? Your research? Yes, probably something to do with research. And how about if you had not gone into heart surgery? What other parts of the human anatomy or body might have held interest for you? Oh I don't think....I think I could have gotten interested in any part. Any part in research. Yeah sure. I got interested in this area largely because Dr. Ochsner sort of took me over, first as a medical student, and he became interested in me.

And then I came under his direct supervision when I finished, I got my degree in medicine, you see. I did my internship and residency at Charity and it was doing research in the vascular field and the circulation and so on and that led to, you see, in time, to the development of, you might say, surgical techniques for some of these conditions. Doctor, is faith in oneself sufficient or must each of us have to have a higher faith, a belief that something out there, something above us, is also participating in this experience of life. Well, I think if you have faith in yourself, you've got to have this other faith, too. Otherwise, you

can't, in a sense, accept yourself as just an organism. I think we have to accept ourselves as not just an organism, but as having a spirit, as having a soul, as having a conscience. And I don't think that's all just chemistry, you know. Secondly, I think that you have to accept the fact that there is this great order in the universe, whether you're talking about the atom or the molecule or whatever it is, it's orderly, you know. It's an order that you can't simply dismiss as being accidental. So I have the strong feeling that you have to have faith in yourself and in some higher order that has created the universe. Is this organism,

us, this human body, this machine that comes to life and, and goes on for a given span which you're ever pushing back that span, increasing it. Is it an amazing mechanism, Dr. DeBakey? Oh it's, it's, it's a miraculous mechanism. Every time I open the chest of a patient for a heart operation and I see that heart beating, I tell the assistants and residents and so on, "Have you ever seen anything more beautiful?" There's a tremendous beauty in the heart, in the way it's made up and the way it's beating and... And you know, it comes to mind what Keats said about a tree, you know. Only God can make a tree.

And I look at that and it's so beautiful and so harmonious and so efficient. Doctor, you, you cure in all kind of ways. You're curative powers are by no means limited to the skill that emanates from that hand. You're quite something. What... Among your patients is the Duke of Windsor and the Shah of Iran. What did you think about the Shah of Iran? What kind of man was he? Well, of course, my relation with him was as a patient, you see, and I only saw that aspect of him when he was quite ill. But I found him to be a rather shy man and, in many ways, a very sad man at this time.

Yes. But certainly I think his sadness came because he knew he had an illness that would ultimately cause his death. But also from the fact that he had tried to do these things for his people, you know. He really had tried. He tried to develop his people, to educate them, to build hospitals for them, to develop them, you see. Very backward people he was bringing into the 20th century. He had tried so hard and he had to a large extent suceeded. But in the final days of his life he obviously had failed and they threw him out and killed a lot of his people. They have since denunciated his policies which were his life. Yes.

But he was an easy man to talk with. He was a good patient. He did what I asked him to do and he related to me very nicely. And I liked him. I liked him. I thought it was sad these things that had happened to him Was the Duke of Windsor a sad man? Because his life, in my opinion, has also failed. Yes. Yes, well, I don't think there's any question about that. Yes, I think there was a certain sadness in his life. I think he put on a good front - I see -, you see. But he was a very nice man in every way, even to the local nurses in the hospital, the technicians. Dr. DeBakey, our time has run out. I have no words to express our appreciation for your coming from Houston and leaving the life-and-death work in which you engage to share the philosophy and thoughts of a Louisianian of whom we

are all proud and certainly, certainly a legend. Thank you very much. I'm proud to be a Louisianian, too. Funding for the production of Legends is provided in part by the Friends of

LBB.

- Series

- Louisiana Legends

- Episode

- Dr. Michael DeBakey, Part 2

- Producing Organization

- Louisiana Public Broadcasting

- Contributing Organization

- Louisiana Public Broadcasting (Baton Rouge, Louisiana)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip/17-784j1z64

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip/17-784j1z64).

- Description

- Episode Description

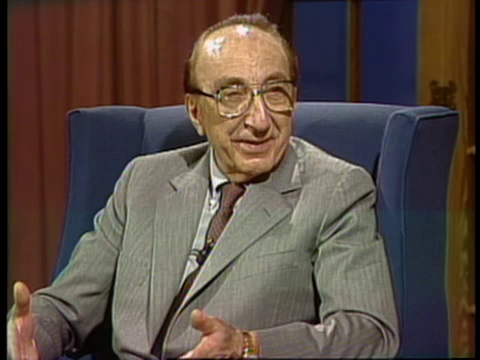

- This episode of the series "Louisiana Legends" from November 19, 1982, features the second part of an interview with Dr. Michael DeBakey conducted by Gus Weill. Dr. DeBakey, a native of Lake Charles, was a preeminent surgeon whose innovations revolutionized heart surgery. He discusses: the evolution of medical research; what he looks for in a surgeon; the emotions experienced by surgeons; the future of heart surgery; getting to know his patients; his belief in a higher power; the beauty of the heart; and his personal impressions of two of his famous patients, the Shah of Iran and the Duke of Windsor. Host: Gus Weill

- Series Description

- "Louisiana Legends is a talk show hosted by Gus Weill. Weill has in-depth conversations with Louisiana cultural icons, who talk about their lives. "

- Date

- 1982-11-19

- Asset type

- Episode

- Topics

- Biography

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:29:27

- Credits

-

-

Copyright Holder: Louisiana Educational Television Authority

Producing Organization: Louisiana Public Broadcasting

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

Louisiana Public Broadcasting

Identifier: LLOLG-106 (Louisiana Public Broadcasting Archives)

Format: U-matic

Generation: Master

Duration: 00:28:47

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “Louisiana Legends; Dr. Michael DeBakey, Part 2,” 1982-11-19, Louisiana Public Broadcasting, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed May 17, 2025, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-17-784j1z64.

- MLA: “Louisiana Legends; Dr. Michael DeBakey, Part 2.” 1982-11-19. Louisiana Public Broadcasting, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. May 17, 2025. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-17-784j1z64>.

- APA: Louisiana Legends; Dr. Michael DeBakey, Part 2. Boston, MA: Louisiana Public Broadcasting, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-17-784j1z64