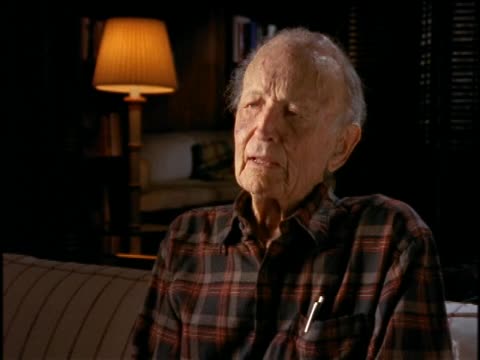

NOVA; To the Moon; Interview with John Leland "Lee" Atwood, engineer, aerospace executive, and overseer of the Apollo program, part 1 of 2

- Series

- NOVA

- Episode

- To the Moon

- Producing Organization

- WGBH Educational Foundation

- Contributing Organization

- WGBH (Boston, Massachusetts)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip-15-cv4bn9z908

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip-15-cv4bn9z908).

- Description

- Program Description

- This remarkably crafted program covers the full range of participants in the Apollo project, from the scientists and engineers who promoted bold ideas about the nature of the Moon and how to get there, to the young geologists who chose the landing sites and helped train the crews, to the astronauts who actually went - not once or twice, but six times, each to a more demanding and interesting location on the Moon's surface. "To The Moon" includes unprecedented footage, rare interviews, and presents a magnificent overview of the history of man and the Moon. To the Moon aired as NOVA episode 2610 in 1999.

- Raw Footage Description

- John Leland "Lee" Atwood, engineer, former aerospace executive, and former overseer of the Apollo program, is interviewed about his role in the Apollo program. Atwood describes how he came to be CEO of North American and how the company got the government contract to create spacecraft for the Apollo program. Atwood details his memories of the Apollo 1 fire, as well as the causes and misunderstandings that resulted in the disaster, and the changes that were made as a response to the fire.

- Created Date

- 1998

- Asset type

- Raw Footage

- Genres

- Interview

- Topics

- History

- Technology

- Science

- Subjects

- American History; Gemini; apollo; moon; Space; astronaut

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:24:21

- Credits

-

-

Interviewee: Atwood, John Leland "Lee", 1904-1999

Interviewee: Atwood, John Leland "Lee", 1904-1999

Producing Organization: WGBH Educational Foundation

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

WGBH

Identifier: cpb-aacip-85454056fb8 (Filename)

Format: Digital Betacam

Generation: Original

Duration: 0:24:21

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “NOVA; To the Moon; Interview with John Leland "Lee" Atwood, engineer, aerospace executive, and overseer of the Apollo program, part 1 of 2 ,” 1998, WGBH, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed March 10, 2026, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15-cv4bn9z908.

- MLA: “NOVA; To the Moon; Interview with John Leland "Lee" Atwood, engineer, aerospace executive, and overseer of the Apollo program, part 1 of 2 .” 1998. WGBH, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. March 10, 2026. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15-cv4bn9z908>.

- APA: NOVA; To the Moon; Interview with John Leland "Lee" Atwood, engineer, aerospace executive, and overseer of the Apollo program, part 1 of 2 . Boston, MA: WGBH, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15-cv4bn9z908