Swank in The Arts; 146; James Surls

- Transcript

Good evening, I'm Patsy Swang. James Sirles is an artist with a lot of energy and that may be very fortunate for he is quite possibly the busiest artist in Texas this month. A new exhibition of his drawings and small wood sculptures is on view at the Delahoney Gallery in Dallas. He is the only artist from this state represented in the Whitney Museum's 1979 Biennial which opened Valentine's Day in New York. And he is in fire, the new exhibition of Texas artists at the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston. Not only is Sirles in that show, he put it together.

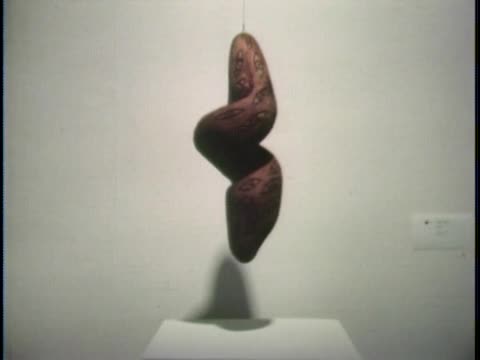

James Sirles was born 36 years ago, the son of an East Texas farmer. He has traveled and lived in a lot of places since, but the forces of his early environment feed him still and he now makes his home near Houston in the small community of Splendora. Sirles doesn't work altogether in wood, but it seems to be the material which reflects most directly both the simplicity and complexity of his art. He uses wood as a friend and a messenger. He never deprives it of its elemental character. You always have a sense of it coming fresh from the forest. Yet it may be highly textured or polished or drawn on. Sometimes it's very, very delicate. And you know by looking at it how much Sirles himself loves music and dancing. Although 1979 should prove to be a most successful year in the career of James Sirles artist, what he is most involved in at the moment is the exhibition at the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston.

He asked 100 Texas artists to send one example of work with no other limitation than that it be conceived to be shown indoors rather than outside. Sirles was in Dallas the week before that show opened. He himself gave it its name and he was full of excitement and happiness about it. Fire. It's called fire. That show was called fire. Well it's really amazing how that show came about for some strange and mysterious reasons that sun's unbeknownst to everybody. Dallas, Fort Worth and Houston both all sort of at the same time had a gap let's say missing in the Contemporary area. You mean in the museums? Right, right. The Contemporary Museum in Houston didn't have a director in order to have a director at Fort Worth Art Center.

Museum here didn't have a curator in that area. So it presented an odd time sort of psychologically it was an odd time. And because that existed there was a tremendous amount of looking going on. People looking here wondering. Also there was a show in Houston that got cancelled which suddenly left a date. And it had like six weeks to maybe total of two months from the time I heard about it to fill it. They were going to fill it with what's known in the museum world as a canned show. They were going to bring a show from somewhere else which is totally valid. But I heard that several people from the museum asked me if I would be interested in presenting a proposal to their board. And sure I'm always interested in something like that. So it had been talked around the Houston area artists at that time were talking about trying to get the board to have a Houston area show. So it was in the air that it take place and I just happened to be sort of in the right place at the right time to push the first domino to make it really start happening.

Once the seed was planted once the board said yes we will let you do this show. Then from that point on it really got going. You know they really considered it high risk in the beginning it was a controversial thing to do it was putting them let's say on the line. They really put their head on the block. Why because it would be an invitational show? Well because I'm not a museum type. Let's say I'm not a curator I'm not a director. Theoretically a show was always supposed to be put together with a certain sort of system to it. And museums follow the same lines traditionally and to let an artist do it. See is that in itself is outside the realm of normality. So that in itself to them at least would have it be controversial. I've had a lot of museum people explain to me why artists never judge shows or put shows together.

You know they say things like well artists can't be objective. I say well of course not I know they can't be but neither can museum directors. Neither can curators everybody's got some kind of point of view. I mean fire is a point of view basically. Well once you have graduated to this position of artist curator temporary is it might be had you decide to who to pick and what kind of show to have? Well immediately that presented a problem. The board was very concerned about my objectivity which I mentioned to the point of they say well look aren't you just going to put your friends in this show? And I said land well sure yeah I'm going to put my friends in this show but if that's all there is to it then that really serves no purpose. I mean that's not really being very visionary if all I'm going to stick a bunch of my buddies in there. So right away I said about saying well what should be done?

You know what if suddenly if I have this opportunity and I looked at it as really being a big opportunity then how would I serve it best? So I thought well Texas is made up of such what I'm going to call a complicated series of stratas in the arts. See that sometimes they overlap and sometimes they don't. For instance it's a well known fact that there is a large strata in the southwest that deal with southwestern art. Some people refer to that as cowboy art or just western art. I mean subject matter. I'm talking about subject matter in the type aesthetics of it. See there's also there's a one strata of art that deals primarily with let's say primitive art. I mean the Veloc's Ward for instance is called a primitive you know I mean well that's certainly questionable. I think that if it could be possible to make cross references in all these stratas and actually mix them all up let's say that I would sort of expect what I'm going to call a cultural phenomenon to take place.

For instance anytime there's has ever been what's been historically called an art scene it was always a place where there was a lot of information being spread around quick. See I mean there was a lot of stuff starting to artist past information back and forth. One element of art didn't just elevate by itself it sort of all collectively came about and that's happening here too. So I think that if I because I'm a visual artist this show primarily deals with visual art like paintings drawing sculpture that that sort of stuff. But I just tried to pick as many different levels of it as I could and put them all in there together and show them as one not necessarily segregate them out in the installation. But actually mix them up which means that suddenly supporters of this guy is here looking at art from this guy see and they're intense the same to elevate art.

It's just they say this guy's good and this guy's not see but if they're there together I think they'll I actually think there'll be something take place. What is it that you'd like to see come out of this what what sort of relationship between maybe galleries people that like and buy art museums what sort of an environment would you like to see happen in this state. I think that this show in a sense is going to sort of be the doorway to the eighties I say that in reference to this art of the past. Well I say since since his on really it was a matter of reduction I mean his on would let a stroke represent one half of a tree or a bush or a limb. I mean it was made up of a composite of strokes reflecting light that collectively made a he orchestrated a picture but he didn't paint all the leaves. So then came Cubism Cubism again started to sort of slice away the image and reduce it to its geometric components say that's like reduction.

Well it followed in through to abstract expressionism which totally destroyed the image in terms of its visual reality and constructed a new reality if you will they would say make red balance with blue. But it wasn't a red arm or a blue shirt it was just red and blue that was orchestrated with some sort of visual harmony. Then it got reduced again the image lost one more step it went to minimalism say now it was reduced to a blue line a red stripe a box a flat piece of steel laying on the floor. And I be a string stretched across the room see I mean valid I'm not arguing whether it's it's validity I'm just simply saying that was the that was the direction that the mainstream was traveling into a reductive sense. Well I think that that the end of the 70s now we're actually witnessing what I'm going to call the demise of reductive art. I think it's reached a natural state of ending see and I think that once we start into the 80s that art is going to turn in a different direction.

It's going to be bent into a whole another in other words the the swings mean the arcs being made right now the reduction has ended now we're going to move back into what I'm going to call more human-oriented art. Art, art that deals more with sort of the human phenomenon of living it's of a personal nature as opposed to being of an intellectual nature which a box is an intellectual thing. See I mean it's it's it's it's it's form and it's purest sense it's reduced to its to its common denominator sort of your box at the future then would be wrapped and labeled. Well I don't know I think that I would say it's going to be wrapped in label I think that it's going to have it's going to deal with a whole lot more than just like the coup calculated nature of reduction I think it's going to be let's say art of addition. Are you talking about richness depth is that the level of humanism that you that you mean detail I'm talking about what I'm going to call let's say it will deal more with passion it'll deal more with the spiritual side of man as opposed to the intellectual side of man it'll deal more with romance I think that art of the.

Of what we'll call here the southern rim or the sun belt see I think that because we've been naturally excluded from the mainstream because we didn't fit into that reductive scheme that we sort of had to sort of develop on our own so I think consequently we've been sort of sitting down here stewing in a way you know me we've been kind of boiling in the pot and cooking and developing our own sensibility and I'm saying that our sensibility has now come full bloom I'm saying that we're actually. We're actually reaching a mature state where you're going to see the arts in Texas and in the southern rim in general blossom it's a natural phenomenon it has to happen it's happening in other areas that are helping us along but the truth the matter is we actually have come along as well see you live what fairly close to where you were born or not you for you but you come out of East Texas I grew up in East Texas I was born in Terrell Texas I grew and I actually grew up in Malacov that's what I that was sort of my first hit was with the real world you might say was there.

We moved around a lot lived in East Texas and I think of East Texas sort of in general as being home and now I live at the bottom part of East Texas but it's still the same sort of feeling you know. I don't know it just makes sense if you grow up somewhere and you get sort of functioning in that rhythm boy it really I mean that's why I ask you to stay in Alaska. You know I mean wine a world anybody want to live in North Pole but if you grew up there you think it's terrific you know and I grew up in East Texas so I really think it's terrific and it really is terrific. That must have something to do with your great warmth and affinity with wood. Well sure I actually think that my two primary forces that and by that I'm talking about dealing with material by I'm talking about forces in relation to material comes from one growing up on the farm having to split fence post and you know make things. I just sort of made things and an axe or a cross cut saw or something like that wasn't an alien too. I mean I come about it in an honest way doing whatever we did just to keep the place functional see so that shows up in my art now all the time.

The other thing was working on pipelines you know during the summer I'd go off and work on pipelines and Louisiana or Mississippi somewhere or go out on the Gulf. I learned how to just I mean because I was around it all time I learned how to think in terms of bending pipe or putting pipe together or welding it together in terms of making some kind of system of order out of it so I use those two things now the two things I learned in school one undergraduate school was to polish wood. So I don't I mean I've sort of I learned how to make forms there and that was important but the other stuff that I learned there I've sort of abandoned so I mean my undergraduate career in terms of of showing itself now has been reduced and my graduate career has been reduced I cast bronze there I mean I I mimicked and mimed my teacher he was an incredible bronzecaster an incredible artist and taught me a whole lot. I got a tremendous respect for him his name is Julius Schmidt he taught at Cranbrook but I didn't really know what I was doing so you know that's not true anymore you know young artists make things and they make things and they make another thing and then they make another thing and they do it because they want to do it but they don't really know why or what or how or they don't know what their messages they don't know what they're trying to say it's just that they're going through all of that sort of that physical process.

And that's what to me schools were all about it's just process learning how to make a something and then you would make another something and if it didn't look right you turn it upside down and you know I mean you just didn't really know what it was but now that's not true. Now the inspiration the visual internal visual inspiration comes the words come then giving some kind of what I would call a poetic or romantic interpretation of the vision and then from the words comes the image from that then comes the sculpture. So the sculpture actually is the last physical manifestation of the process the sculpture ironically is like a year or so behind the concept you know which is another strange thing about a show.

It's when I walk into a room and see a bunch of my art setting around in it I mean it's almost like it's history it's past you know I mean it sort of has already taken place in a way and that's pretty strange. The drawings are the most important really the drawings to me are they're the loses they're the freest they're the most honest in a way they're the most uninhibited. I never use an eraser I just took my eraser and threw it away I mean I I feel like that if my if my vision is set to the point that I know where it's going then there's sort of in a way no such thing as a mistake. On the paper you know I mean I was drawing once I was doing a drawing about my daddy and I was coming around the shoulder and coming down the arm with it when I got to the arm for some reason I kind of made a jag in it you know and and and wait a minute no I'm telling it wrong I come around and made the shoulder and then I stopped and then I was going to come around up the coat and make the inside of the under part of the arm and come around and down to the to the cuff and back up and meet the line and I started.

But I somehow my vision got warped and I missed the line so the left side of the arm was supposed to be the left side but it wound up being over on the wrong side. So I made like an optical illusion thing take place there but what it meant was is that his arm was totally severed and moved over a half a notch. So I made these two little lines to bring them together and it looked funny but somehow or another sense that that's where I was supposed to be and I kept thinking about it and looking at it and I realized that my daddy was in a wreck in 1951 and over no cliff. I'm sure he's leaving a bear joint somewhere but he got his arm all mashed up you know they had a bunch of rods and stuff in it and so I realized that that kind of that little weird thing there about his arm was real. It came out of some memory it came out of some memory you know just just a kind of an unconscious jog in a way of memory and that really figures in there somewhere I mean with me it does.

I like that sort of registration of facts. Well it seems like a simplistic question but how has all of this recognition affected you in the way that you think about your work and your own kind of production. Yeah I think that basically what happens is that well let me give an analogy it's a general analogy but then at the end of it I'll tie it to myself. I think that it's like when you first learn about the ABCs you really don't know what they are you know that an A is an A but you don't know what to do with it. At some point you actually learn all of the letters and then you learn how to orchestrate them you put them together and you make words out of it once you have achieved the capability of making the words then you can make sentences and then paragraphs and then novels and then you can write history books if you want to. And the same things true in art you have to develop a vocabulary alright the vocabulary that you develop and has to be of a personal nature see I mean it's like my art in essence represents my own vocabulary each time I learn a trick and I will then go back and use a thousand times in my art I mean it's such a repetitive thing that it's like you'll see an A crop up in ever sentence you know or a B crop up in ever sentence but this.

But it spells something different and all of it has to deal with what goes on in my own personal life I mean if it if it doesn't come out of there then it's sort of maybe not really as honest as I want it to be and I think that art by definition has to tell the truth that art can't lie to you if indeed it is art you know decoration can lie to you sometimes. But then that's not really art anyway so that's not what we're talking about well just go back in history and pick any great artists from Michael Angelo to Rembrandt to whoever Henry Moore I mean they all they all develop see their own vocabulary now in the beginning they didn't have that you don't just come full bone into the world with an existing vocabulary so you have to pick that up that's the reason when I was an undergraduate school I work like Charles Pettworth. When I was in graduate school I worked like like Julia Schmidt you know I mean you mimic him mind you know you make stuff that looks like other stuff that you've seen.

Now during the process you're constantly trying to elevate it to the point that what you're really doing is just feeding off of them but in the process you're developing your own system of order and the first thing you know you spin off. I mean I have heard it said before and I mean this is one of the dumb things that you could say that whether it's true or not may or may not be but it's like if if you study with a master and 10 years later you still reflect a master you will never be a master you know I mean at some point the sever severing process has to take place. Well that's incredibly difficult to do I mean because we're such creatures of habit that once this visual system has been instilled into us we constantly keep on repeating it and repeating it so it's not easy to make the transition. Now in relation to let's say the public and commercial art the public are the same creatures of habit what they have seen they understand. So once they see a particular system of order then they say they understand that particular system of order once they understand it then they say they like it once they like it then they'll support it.

Okay so what happens is as the visual system is developed here it comes up by the ground it's over here growing so the public hadn't seen it here's the world over here they hadn't seen it. It's already up to a three four five six seven eight years old maybe the public still hadn't seen it a few public has seen it but not enough to really integrate it into the vision of the society. All right maybe by the time the person is 56 years on down the line then first thing you know the public actually has got an awareness of it and by the time they get up old enough to where they're ready to pass on into the into the unknown they're accepted. See they're accepted that's the reason people say well you got to die before you get accepted it just simply has to get integrated in commercial art is already integrated in. I mean for instance Andy Warhol's Campbell soup cans was integrated in before it ever his ever even hit the market. He specifically and will tell you this of course he specifically chose symbols that were already integrated already in there.

See they existed already Maryland Monroe already in there already synthesized catalog slotted away ready to be accepted consequently everybody said oh my god that's wonderful we will accept that well now. Keep in mind that all humans have a certain sort of innate desire to create I mean we all do see and and that's what makes us humans. All right plus we all develop some sort of visual system as to what we think is right and wrong in the visual world. See if we like a safe we see something we're used to it the patterns come into focus all the references show up right so consequently we can accept it well. I have a saying about the art of today is the culture of tomorrow I mean that's the I mean back to that fire business down there. That's the reason contemporary wings of museums and that's the reason that museums oriented in a contemporary direction always have problems it's inherent they have to have problems because people walk

in the front door they look around they say I don't understand this therefore cachunk iron curtain falls but that's true all the way across the arts and any of them. In any of sure yeah and that I'll say that in reference to arts. Well if fire really makes the mix you you will have shot up a bear won't you yeah I'm shooting for a bear I really am. I actually shot the bear the mere the mere fact that they they let the show take place was shooting the bear the fact that we now have like city politics support was shooting the bear you know I mean. There's been a lot of bear shot lately and and the point of fire is is that that we actually can shoot the bear is because the bear is ready to be shot listen. Tut brought southern Louisiana over $80 million in revenue you know Dallas goes to Houston puts up billboards saying come see Pompeii the art dollar is business now I mean they know that by supporting the arts that they're elevating their whole structure consequently they're actually ready to support the arts that's going to bring us in the door.

I don't know anybody that's in the middle of it. I'm trying I sure am thanks so much for coming James I'm really glad you're here my pleasure it was a pleasure thank you. Thank you. Thank you.

Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.

- Series

- Swank in The Arts

- Episode Number

- 146

- Episode

- James Surls

- Producing Organization

- KERA

- Contributing Organization

- KERA (Dallas, Texas)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip-f440bb1f8ac

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip-f440bb1f8ac).

- Description

- Episode Description

- Patsy Swank interviews artist James Surls about his artwork and exhibitions.

- Series Description

- “Swank in the Arts” was KERA’s weekly in-depth arts television program.

- Promo Description

- Filmed stills of Mr. Surls artwork including wooden pieces and drawings.

- Broadcast Date

- 1979-02-21

- Created Date

- 1979-02-17

- Asset type

- Episode

- Genres

- Talk Show

- Topics

- Fine Arts

- Subjects

- Fine Art; The art of James Surls.

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:29:46.385

- Credits

-

-

Director: Parr, Dan

Executive Producer: Howard, Brice

Interviewee: Surls, James

Interviewer: Swank, Patsy

Producer: Swank, Patsy

Producing Organization: KERA

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

KERA

Identifier: cpb-aacip-f3d23d3aa83 (Filename)

Format: 2 inch videotape: Quadruplex

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “Swank in The Arts; 146; James Surls,” 1979-02-21, KERA, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed July 17, 2025, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-f440bb1f8ac.

- MLA: “Swank in The Arts; 146; James Surls.” 1979-02-21. KERA, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. July 17, 2025. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-f440bb1f8ac>.

- APA: Swank in The Arts; 146; James Surls. Boston, MA: KERA, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-f440bb1f8ac