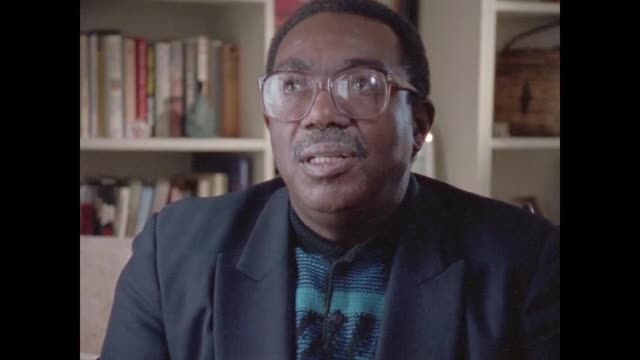

Eyes on the Prize II; Interview with Peter Bailey

- Transcript

Mark's team A, thank you, oops, did again, second sticks. Second sticks. Go ahead. Peter, you're talking about some in 1962, the first move didn't solve Parliament Malcolm for the first time. Can you give us your reactions? Well, I had moved to Harlem in the summer of 1962 and we moved it on a Friday, so that Saturday morning, instead of my roommate and I, instead of unpacking, we decided to walk through Harlem. We were living right off of Linux Avenue, which of Harlem's main drags, we walked down to 100, we walked down, we got to 116th Street and Linux Avenue and saw a crowd gathering. And we asked what was going on and they said that Malcolm X was going to speak. At that time, we had heard of Malcolm, but we had only heard the negative things that you hear from reading the newspapers, so we didn't know him, so we decided to stay and listen to what he had to say.

And he spoke for about almost two hours and we listened and you began to, my opinion was that you would never listen to him and be the same again. If you disagree with every single thing he was saying, he still forced you to deal with certain things and think about certain things that you had been kind of not really dealing with and thinking about before. So we became totally fascinated and I found myself personally being intellectually resisting what he was saying because I had come out of the integrationist wing of the movement. And but emotionally, I was very, very pulled by his analysis of the system. I had never heard the system analyze and presented in that way before. It made sense to me, it really made sense and I had to, I was resisting it intellectually, emotionally, I was very pulled to it and we find out that he was going to be speaking that every Saturday afternoon, so we made it definite our purpose and we were going to be back that of following Saturday and we were and we began to listen and every time he would mention an article, a magazine, a book, we would go and try to find that article

and magazine and book to read. It was, in every sense of the word for me, it was a university of the streets, that term is kind of overused, but I think literally it was a university of the streets in the sense that we were learning. It was a learning experience in the absolute most, the best sense of that term learning. And for about five or six Saturdays, I felt as though I learned more about how the system worked in this country that I had learned in all the years, you know, prior to that just by listening to his analysis. So to me, it was, it was the beginning of my higher education though I had already had two years of college by the time this happened, but to me that was the beginning of my higher education. Well, what happened was that, you know, in early 1963, kind of, in my opinion, as a response to the March on Washington, which I think occurred in August 28th, the 16th Street Baptist Church

was bombed in Birmingham and four little girls were killed in that bombing. So at some time, I think in late September of 1963, there was a rally on 125th Street in Harlem, in front of the then hotel Theresa, which is where all the major rallies were held in Harlem. And it was the person who kind of seemed to have been put the rally together with Jackie Robinson. Now, Jackie Robinson had been my childhood hero, growing up in Alabama. I remember when he broke into baseball, he was my childhood hero. But he, I kind of forgot about that when he began to, he became, he was very hostile to brother Malcolm, and after that began to be involved with brother Malcolm, I kind of switched my allegiance over to brother Malcolm. But what happened that day was that there was a rally showing our support for those little girls down in Birmingham. And Jackie Robinson, I mean, Malcolm X was the first speaker, and he spoke, and then about, I guess maybe eight or nine other speakers spoke, including Earth the Kid, by the way, who was at the Apollo Theater at the time.

There's another story, a whole story there. But when there was over, when the last speaker spoke, you know, Jackie Robinson thanked everyone for coming, and the crowd started yelling, we want Malcolm X. They wanted brother Malcolm to speak again, and they kept saying, we want Malcolm X, and they wouldn't leave. And Jackie Robinson kept saying, well, the rally is over, you know, everybody should go home, and then the crowd started really getting belligerent. They were jumping on cars and stopping traffic. And brother Malcolm, who had been kind of leaning up against the chock full of nuts, which was right there at the bottom of the hotel to recent, got up on the platform again, and kind of said to the crowd, you know, brothers and sisters, you know, let's don't do this. You know, we, the rally was for a very important cause, and we've, you know, we've had it, and I think everyone, you know, should now go home. And immediately the crowd just quieted down and moved on out, and it was the, my first time witnessing the ability that he had to move people and how people responded to him. I mean, they just faded away. There was no more, all of the, the raucousness and all the jumping and screaming and yelling,

stopped, and everybody just left. And within a few minutes, you know, the area was, you know, it was clear. And I remember thinking to myself, you know, people really, you know, responding, I had never seen anything like that before. And it was my, it was an example to me of his ability and how people, you know, responded to him and his ability to move people. And he had a certain kind of integrity that people responded to. And that was that. And I always stayed etched in my mind. And at this time, I still did not know him. I had not met him at this time. I was still just kind of, you know, following around, wherever he went that I could be there, I would go and listen. But because I was not a Muslim and really had no intentions or inclination to become a Muslim, I was never able to get to know him before this time. Okay. Okay. Mark it. Leading into January of 1964 and what led up to you family meeting Malcolm and working with him. Good. That came about because of someone that I knew what had happened is that in December of 1963, brother Malcolm was suspended from the nation of Islam.

Repeat that sentence again in December. Oh. In December of 1963, brother Malcolm was suspended from the nation of Islam. This came about as a result of statements in the press indicating or trying to imply that he had rejoiced over the assassination of President John Kennedy. You know, that occurred in November 22, 1963. And what about a statement that brother Malcolm had said at the time was that it was a case of the chickens coming home to roost. And now if you grew up in the South like I did, you know, everyone knows that said you hear it all the time from the older people, you know, something about the chickens coming home to roost. What he was saying was that he had been saying all along that the violence, you know, that whole violent atmosphere that had been created as a result of the movement the bombing and Birmingham and all the other things that had gone on. And by the government not doing anything about this and in this case, Kennedy was the president at the time. They had created a whole atmosphere of violence and finally, this violence had reached the White House. This is what he was saying when he said the case of the chickens coming home to roost.

Well, of course, the press used this and reported it as though he was rejoicing over Kennedy's assassination. And eventually he was in some time in December, he was suspended by the nation of Islam. Now in the latter part of December or early January, I'm not exactly sure of the date. A friend of mine, a young lady who I knew approached me when we were having lunch together. And she said, how would you like to be a part of a new organization? So I said, fine, I said, what kind of organization did she give me some very, very brief details? I said, it sounds very interesting, I would be very interested in being a part of it. So she said, well, I'm going to call you on Saturday morning around 8 o'clock and I'll tell you where and everything, you know, it was all very secretive. And so I said, okay, she called me, told me where to meet and what time. I went over there, it was a motel in Harlem, a 153rd student, eight time a new in Harlem. And when I got over there, I saw John Henry Clark, I saw John Killens, and a few of the people, they were two people, I definitely recognized, there were a couple of people that I had

seen around, but I didn't really know that well. But then I knew them, and I was, you know, my curiosity was aroused, and so I'm wondering what is going on here. And we sat around and talked for a while. And then in walks Brother Malcolm, now when he walked in, I said to myself, oh, you know, this is going to be serious. I had never, I had no idea up until he walked through that door that he was going to be involved with this new organization. And that's when I found out that he was planning on forming an organization that would, where people like myself who were none Muslims could work with his program. And after we sat down and we talked, and we began to meet there every Saturday for about three or four weeks, maybe longer, I think maybe in five or six weeks, we met there every Saturday, we discussed the organization, we developed a constitution, we got developed the name, the organization of African American Unity, which is after the organization of African Unity, which had been formed about the same time over in Africa, so we called ourselves the organization of African American Unity. And it was out of that, I met him that day for the first time, and nothing significant

happened. I mean, I was just another one of the people there, but I remember thinking to myself, you know, that I think I had finally found an organization that was beginning to appeal to the types of things that I was thinking about at that time. I had been in many, in the WACP Youth Group, Core, the Harlem Rinstrike Committee, I had been through all of these groups, and eventually I would pull out because I actually get frustrated with them. But I felt, you know, this organization sounds like it's going to be very interesting, and it was my time, it was my first time after hearing him now, of actually getting the chance to speak to him and to begin to move and work with him with this organization. And we met and we've announced the organization publicly, I think, around June of 1964. We publicly announced the organization in early June, and shortly after the announcement, he went off to the organization of African Unity Meeting in Cairo. Thank you. You're talking about how this organization satisfied you more than any others in the principles behind it, or how it folded into my balcony.

OK, you know, by this time, I had basically been following Brother Malcolm for almost a year and a half. We talking now, the early winter of 1964, and I had first started following him in the summer of 1962. So for a year and a half, I've been kind of, from a distance, supporting his organization, going to rallies, you know, listening to speak, following my television radio. So when he walked to that door and I saw that he was going to be a part of this new organization, that was very, very, to me, that was a tremendous opportunity for me to become involved in something that I thought was really serious. And as we just set back, and the thing that amazed me is that he responded, he wanted to know what those of us thought who were there with him in the organization. He did not come in and say, you know, this is the organization, this is what's going to happen. And we sat down and we worked out a constitution. And basically, we had this different areas. We say politically that black people should control the politics of our community. We believed in an independent black political party.

We did not believe being members of the Democratic Party or the Republican Party. Economically, we talked about collective economic activities that we were underutilizing our economic power in the society and that we could only move and we did it on a collective basis. We had a program for self-defense. And of course, this was always one where the press accused him of advocating violence. And basically, the thrust of his policy in self-defense was that in those areas where the government was either unable or unwilling to protect the lives and property of black people, then they had the right to protect themselves. Now, if you know what was going on with all those bombings and things that were going on during that time, we considered that to be a very logical position to take for an organization. And then we had policies on social policy. We talked about the necessity for guardianships so that black youngsters who got in trouble instead of them going and being into the courts, they might be able to parole them off into a guardian organization, which is what other groups have done and still do consistently. And I don't think that we still not involved in any kind of serious manner, which keeps

the kids from getting a court record very early, those who some, of course, can't be stopped, but some who can't. So we talked about that as part of our social policy, but the one thing, and these were all different approaches from most of the other organizations that existed at that time. But people want to send the biggest difference that we had with them is that I think we were the first and major organization of that time who had a foreign policy. I mean, we had a foreign policy. And it was based on Brother Malcolm's contention that it was to our advantage and our best interest in talking about African-Americans to have strong relationships with black people all around the world, but especially on the African continent. It was his contention that this was our only real place where we would get protection. And an example he used, which was very, very interesting to me, which I always use when I talk to students, is that he said, there used to be a time when people would say, you don't have a China-Mun's chance.

And I can remember as a kid hearing that, he said, but since China has become a force on the world scene, you don't hear anyone saying anymore, you don't have a China-Mun's chance. Because a strong China, a respected China, is a protection for Chinese people of Chinese to sit all over the world. And he said the same thing with Jewish people. He said, Israel had become a protective. You mess with a Jewish person no matter where it is in the world. You mess with somebody, they had somebody who was prepared to organize, to defend them. He felt as if we had to develop that same kind of relationship with Africa. So he built the foreign policy. He had a foreign policy. He used to travel. We called him our foreign minister and our secretary of our combination of foreign minister and secretary of state. That's why shortly after the organization was formed, after the OAAU was publicly announced, he went off to attend the organization of African Unity meeting in Cairo. This was very important because, number one, it was the first time that the African-American had been allowed to sit in on the meeting. He did not participate. He was not allowed to speak. But he was allowed to sit in as an observer. And while there, as an observer, he distributed documents, you know, outlining his position

and trying to make the African see where it was in their best interests to have a strong relationship with us. It was in our best interests to have a strong relationship with them. It was in their best interests to have a strong relationship with us. And if you see some of the documents from that time, he outlines the reasons behind this. And so we were, we had a foreign policy, you know, the OAAU, unlike some of the other organizations of that time. We had a foreign policy. And Brother Malcolm was our secretary of state and our foreign minister. And he spent a time over there. And one of the results of his spending time over there was a statement issued by the organization of African unity, supporting the announcing what was happening in Mississippi, because, you know, this was the summer. We now, we're talking the summer of 64, the killing of Cheney and Goodman and Schroiner, those three kids, black one, black kid and two white kids who were killed in Mississippi. This had happened.

There had been other bombings going on. The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was being organized and trying to replace the racist Democratic Party in Mississippi that came to Atlantic City and they refused to seat them at the Democratic Convention. So all of this, you know, was happening at this time. And, and for the organization of African unity to issue a statement, recognizing what was happening at this time was a very, very important step. And it was late. This foundation was laid by what Brother Malcolm did at that OAAU meeting. I thought that was a, that was a very significant move. And I really believe that this was his success in doing that and his success later in the summer besides issuing that statement when the situation broke in the Congo, where some Belgium nationals were killed in the Congo. And there was a big to do over here about those terrible Africans, you know, killing Europeans in the Congo at the UN. Some African diplomats for the first time in speaking before the UN connected the situation that was happening in the Congo to the situation that was happening in Mississippi.

This was, and they did this because of the foundation that Brother Malcolm had laid. So I mean, our foreign policy was beginning to connect up. And I think that that was when he began to be considered seriously, seriously, and dangerous. Because I remember he told us that when he was traveling in Africa at that time in Kenya, at some of the fair that he went to, because in Africa he was treated like, you know, like he was, like he was, I, a foreign minister of the African-American people to Africa. And in Kenya, I think it was, the American ambassador there, some of the fair that he was attending that the American ambassador was present, told him that he had no right, no right to come to Africa, and mess with the Americans foreign policy. And Brother Malcolm's response to him was, if you were not doing the things that you were doing or the things that are happening to black people in America were not happening, then, you know, there would be nothing for me to say. So you know, you would not have to worry about anything that I say while I'm over here in Africa. So the government began to take, you know, began to look at what he was doing and began to realize that this man was very serious.

He was very serious. His, what he, what he ultimately was aiming for at a foreign policy level was to have the government, the US government, have to defend its interaction in terms of the racist attacks that were going on at that time, to defend its actions before the U.N. commissioned on human rights and take it before the World Court. Now, of course, we all know that if whatever the World Court decided, the American government could say, you know, we don't have to pay any attention to that, you know, we were powerful or, you know, it doesn't mean anything. But the fact that they had to go and do that would have been a tremendous propaganda loss. And I think that was, they did not want that to happen. When the backup began to talk about the backlash, and its purpose, when we were talking about the publication, the communication itself, when we were talking about that, the news were the backlash. Okay. Well, you know, one of the things that Brother Malcolm taught us, and it was the reason today was eventually why I entered being a journalist, because at the time I had no intentions of being a journalist, was the importance of the information of having the correct information on which to base whatever actions you were planning on taking.

And another thing that he taught us was that you could not depend on someone else to get your information out. You had to have your own means of getting your information out. So one of the first things we did was to form a newsletter. This is no one else, you know, took the job. I took over the job as editor of the newsletter. The first three issues I think were called the OAAU newsletter. And then after that, we named it the black lash. And it was kind of a takeoff, because at the time there was a lot of talk about the white backlash. You know, there was a white backlash developing over things that had been happening. And so we decided to call our publication the black lash. And that's how it became. It was Xerox copies, you know, it was nothing fancy. But when you look at it, we had a lot of information in there that was not being presented anywhere else. The speeches that he made in Africa, we presented the whole speeches. The African nation's declaration supporting our position in this country, we published that.

We published Sheikh Muhammad Babu's whole speech when he came, he spoke in Harlem. And so we used that publication and we sold it for five cents at our rallies. And it became our publication. You were getting information out. Okay. Okay. Okay. When I'm thinking of talking about things about the Malcolm, go ahead. Okay. Okay. Another thing that he taught us, and this is very important, too, that we learned was that be careful with words, because words can get you a lot of trouble. I remember I wrote when 1964 with the Harlem uprising when this policeman was accused of killing this young boy. I had written a paper, something for our newsletter, describing it as a murder. And I read it to brother Malcolm of the phone. He was in Cairo at the time, despite the fact that some New York newspapers were saying that he was in Queens directing the uprising. He was in Cairo. And I read it to him of the phone and I would describe this as a murder. He said, Brother Peter, you can't use a murder, murder is a legal term. And you can only use that once the person has been convicted. He said, use the word killing, because you know he's going to be acquitted.

And if he's acquitted, then he can sue you for liable and defamation of characters. So we went through 500 copies and changed the word murder to killing. And I still have copies that were you wrote killing at the top and scratched out the word murder. And sure enough, later on, when Gilligan the cop was acquitted, he sued SCLC and core for distributing information and public information saying that he was a murderer. Cut. We got a time call, 10, 4, 3, market. Okay. The last days of his life, you were talking about a fire bomb in France and the last day, the helicopter. Okay. Well, by the winter of 1965, there were three things that happened right in a row. Because he was banned from France. His home was fire bomb and he was assassinated. Now to me, and I'm looking now as back on this, it was like somebody had said, you know, this guy's got to go.

First he landed in Paris, the parents government would not let him in, they shipped him back to London. That happened. The following week, he was home. His home was fire bomb, his wife and children in the house. They got out, they lost everything, but no one was injured in the fire bomb. And then the next Saturday, the next Sunday, I remember, the next Saturday, we had a meeting in the OAAU and it was decided that from then on, everybody was going to be searched who came to our rallies and we had a big rally schedule the next day. And brother Malcolm said, no, you know, he didn't want people searched. You look back over now, we should have told him the same thing that they tell Reagan, you have nothing to do about your protection, you know, we make this decision. So then we went on and we went to the Audubon ballroom the next day for the rally. When he came in that Saturday, I had written something the day before saying we still support him. And again, he looked at it, he told brother Peter, you can't say this because you said like there's something, you know, getting trouble.

So I put it off to the side. So when he came in the next day, he called me backstage. And the reason he did that, he thought that he knew that he said, you know, I know you were very hard on that and I just want you to understand why I said, don't do it. I said, I do understand. I understand exactly what you're saying. We talked very briefly, there was an article about the Deacons for Defense and Justice in the New York Times. I showed him the clip and he said, it was about time, it's very good to see some brothers now talking self-defense. There was a Louisiana, a Louisiana that they decided to do this. We talked about 15 or 20 minutes more about different things. He said, told us that he was going to go to Mississippi to speak, to SNCC and then he was going to come back and really work on the form of the organization. And it was about five or six of us backstage at the time talking to him. And then we had decided that this Reverend Glamison was going to come in and make a peak to the audience about getting some clothes and supplies for his family. So he said, does anyone here know what Glamison looked like? And I said, yes, I do. So he sent me down front to wait on Glamison when Glamison came in. I was supposed to bring him backstage. So I'm sitting down front waiting for this in the little room off the main ballroom.

And you know, this place is like almost a football field long. So I heard Brother Malcolm say, I said, I'm a Laker. And the next thing I heard was shots. And I ran into the main area when I started hearing the shooting. And I got knocked down and I laid on the floor to people running by me and I heard screaming and crying and shooting. When the shooting stopped, I jumped up and ran down the length of the ballroom, jumped up on the stage. When I got there, Mrs. Kochiyama was holding him in her arms. Someone had pulled his shirt open and you could just see the bullet holes all in his chest. I kind of felt then that it was no way he was going to survive. He was kind of gagging. He was laying on the floor. He was kind of gagging. I remember jumping off the stage and wondering, had anyone gone to get the doctors? But some brothers had already gone over to Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center. No doctor from there would come over. So they took a card and rolled it to the streets, put him on it, and took him back over to the hospital. But I remember about that time that there was some police there in that place.

We know there was undercover cops. I remember I saw police in uniform. And they were, when I can still see them with all this chaos, people laying on the floor, a lot of screaming and crying. This is, you know, immediately afterwards. And they were walking very casually through the place just looking around. Nobody looked at them. There was any kind of real serious effort being made. And I really think that the only reason that they eventually was a trial was because one of the brothers had disobeyed Brother Malcolm, who said, no weapons. And one of the brothers in our group had brought a weapon with him. I didn't know he had brought one, but he had been able to shoot this one guy when he was running by, slowed him down, and he got caught by the crowd outside. And I really think they would have stomped in the death of the police and not taken him away from him and put him away. And that was the only reason I think they had a trial. I think if he had gotten away like the others did, then never would have been a trial. It would have been like, well, we're checking things out. We're investigating. But because he was caught and so many people saw him get caught, they had to be a trial. I think the assassinations, I think, back over it now, was done like it was for three reasons.

Because he could easily have been assassinated in some dark corner as he was going home. One, to intimidate his followers, which was successful. You know, we can shoot you, lead it down the middle of the afternoon. Two, to cause all kind of dissension between the group, you know, who's in the group. Somebody in the group is obviously a plant with the police. Who is it? And three, to cause a shootout between the Muslims, the nation of Islam, and brother Malcolm's people. That's the holy part of the whole thing that did not succeed because brothers in both group had a cool enough head to keep a blow up from happening. And when it did not happen to immediately have the assassination, that night, the mosque was burned to the ground. Now, there's no way that anybody associated with brother Malcolm could have gotten to that mosque that evening and burned it to the ground the way it was. And then again, I think that was supposed to lead to the shootout. And then the shootout still did not occur. That was the only part, I think, of the game plan that did not work that day in terms of his assassination. And with brother Malcolm being assassinated, the organization, which had cost, unfortunately, had built around him.

I mean, instead of around his philosophy, it was around him. It kind of fell apart. But when I think back over him now and when I talk to people and they want to know what he was, you know what I always tell people? He was a master teacher. And there is no greater loss to the community than the loss of a master teacher. And those of us who work with him and who learn from him, we now have to kind of spread his ideology, his philosophical positions to, you know, to other people. And some of us are still doing that. But he was a master teacher. He taught us. I remember before when I kept talking about how he taught, he taught us. No institutions, what did this man lead as a master teacher? I think that he left changed minds. He left us with a new way of looking at this society. He left it with a clearer vision as to what had to be done and we were to develop, you know, our power as a group.

He talked about self-determination. I mean, this is still important. He talked about self-defense. He talked about education. Anybody who say they follow Brother Malcolm and who do not believe in education is that, you know, it simply is not following him because he believes very strongly in education, but they write kind of education. He believed in responsibility. I mean, he could be very critical of Black folks, you know, with some of the irresponsible things that he felt was going on. He insisted upon that we must be responsible for our own communities. He believed, as I said, he had an international of, he made most of us look abroad and not just in that emotional sense because so many people who only think about Africa was very emotional, they got cut off, you know, he, he, he gave very emotional and very practical reasons why we had to have an international, apostue and international positions. He was a, he was a teacher. He taught, he left, like any teacher, he left behind people who then take what he has done and present it onto other people to keep it, you know, perpetuated. When you think about a teacher, a master teacher, and I developed a concept from dance because

they always talk about the master dancer, or even a person who's a great dancer will go listen to a master dancer teach. That's the way I felt about Brother Malcolm here, that same kind of appeal. And he left that thing with us to develop, to learn, to develop our minds, to, to continue to move, to continue to work, to continue to, to try to, to, to organize our Black people around a, a unified concept, not because we feel as though we can be isolated in the world or have to deal with other people, nobody believes that, that's impossible, nobody can function in the world. But that, when you deal with other people, that you deal with them from position of respect and power, and, you know, and, and that you are not sitting at the table asking all the time, that you are there because, you know, and you can demand just as much as everybody else can. He taught us that, that, that we must, that our minds used to say that the revolution that we need is a revolution of the mind, that is our minds that need to be, you know, revolutionized, and that we develop ourselves and develop our mentalities, and develop our minds and then function on that level, we'll, we'll almost automatically do the correct

thing on a political and an economic level. He could analyze the system, you know, I never could, you could never look at the American system again after listening to him. I mean, even when you talk about slavery, I remember he told us the three kinds of people involved with slavery. You know, you never heard about that before. His legacy, his legacy, he was a continuation of the whole Black nationalist concept. He was a follow of Mark Scarvey, Martin Delaney, and people of that type, people who still, he was not some isolated, he was a part of a continuity in Black American history, and it is the, it is, and his legacy was that he reached more people with it than anyone else did. And because I'm going to say that he was better than these men who preceded him, but because of the change in the time, there was more better communications, you were able to reach many more people in many more different kind of ways with television, for instance, that they did not have. So his, his message, he carried the nationalist message further than any of them had been able to because of the, of the times in which he, in which he operated in.

And Elijah Muhammad was also a part of that, you know, despite the fact that we may

- Series

- Eyes on the Prize II

- Raw Footage

- Interview with Peter Bailey

- Producing Organization

- Blackside, Inc.

- Contributing Organization

- Film and Media Archive, Washington University in St. Louis (St. Louis, Missouri)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip-7f58ead6ffb

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip-7f58ead6ffb).

- Description

- Raw Footage Description

- Interview with A. Peter Bailey conducted for Eyes on the Prize II. Discussion centers on Malcolm X, the Nation of Islam, Elijah Muhammad, and the Organization of Afro-American Unity.

- Created Date

- 1988-11-14

- Asset type

- Raw Footage

- Topics

- Race and Ethnicity

- Subjects

- Race and society

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:31:20;13

- Credits

-

-

:

Interviewee: Bailey, A. Peter

Interviewer: Blue, Carroll Parrott

Producing Organization: Blackside, Inc.

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

Film & Media Archive, Washington University in St. Louis

Identifier: cpb-aacip-f7946f5cb22 (Filename)

Format: 1/4 inch videotape

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “Eyes on the Prize II; Interview with Peter Bailey,” 1988-11-14, Film and Media Archive, Washington University in St. Louis, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed August 2, 2025, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-7f58ead6ffb.

- MLA: “Eyes on the Prize II; Interview with Peter Bailey.” 1988-11-14. Film and Media Archive, Washington University in St. Louis, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. August 2, 2025. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-7f58ead6ffb>.

- APA: Eyes on the Prize II; Interview with Peter Bailey. Boston, MA: Film and Media Archive, Washington University in St. Louis, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-7f58ead6ffb