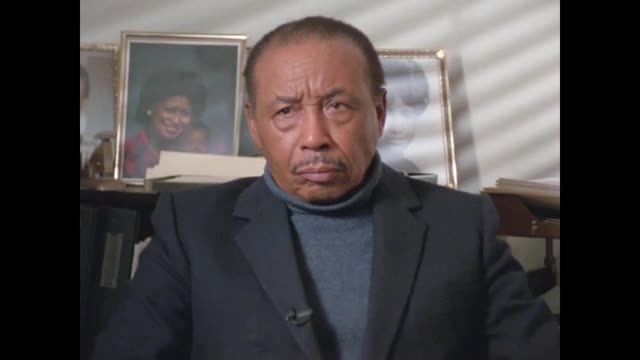

Eyes on the Prize II; Interview with Floyd McKissick

- Transcript

Mr. McKissick, in 1966, he became the National Director of Chorus, succeeding James Farmer and I wonder if, first of all, did that change of leadership suggest any deeper philosophic changes going on in court at that time? Not necessarily so. Farmer and I had been associated and in the movement together and during the times that he was a part of the time when he was the National Director, I was serving as Chairman of the Board. I had been elected as Chairman of the Board in 1963. So we were both working hand in hand and together the whole time. I think that the times had made some changes necessary to occur, just events had occurred and we were both aware, the organization was in a state of change, a normal state of

change as events occurred. What were some of those changes? I think that we had been, previously core, had previously been, had been with a great church background, we had been in the northern area and not so much in the south and it had been with interracial teams working together in the south, you didn't have a whole lot of white people that wanted to join with you and work with you. So quite often, core chapters had very few white people in the south as compared to the north, except in towns where you had universities, say like in Durham, where I was situated, we had a number of whites because we had the University of North Carolina and we had Duke University. So therefore, those two core chapters where you had a pretty good group of, the group

was fairly well mixed. Wasn't there sort of a philosophical change happening within core at that time that maybe whites weren't quite as appropriate to be doing some of the organizing work and what there was a little bit of change happening there? I'm asking because it's going to come up again and a little bit bigger. No, I think that you might be referring to some isolated incidents but certainly not a matter of policy because certainly that we went, we were in Mississippi and they confedered organizations which was then called Kofo in Mississippi and we had as many white students with core as black students. Okay, let's just have to make sure all the systems are working and I'm going to go on things. Okay, describe for me how you heard about the student of James Meredith and what did you do then? I was called from Memphis Tennessee by a friend, associate of James Meredith and was told that he had been shot.

We were in our office then I think at 38 Park Row. I returned the call to find out how Meredith was, he was in the hospital. Meredith and I had had a relationship. We knew each other from the NAACP of many years in the past. I had, we had both been, had been the first to go to the University, I was the first to go to the University of North Carolina, he was the first to go to Mississippi except his situation was far more publicized than mine. So from the NAACP days we had known each other and after he came to New York we were associated with each other. So when you heard he had been shot I want to get you down into Mississippi. Well I agreed to come to Mississippi immediately. He requested that I come to Mississippi. I went to Mississippi and of course upon arrival we immediately went to the hospital.

It was the Congress of Racial Equality that issued the first call that we should go down there in John Meredith and continue to march. Why was that necessary to continue to march? Our feeling was that what Meredith had done exemplified the kind of thing that would be happening in the future, the right to walk on the streets by yourself. Rather you were an individualist, a solo man or whatever. You had a right to walk free and unmolested on the streets of Mississippi, carrying a bandhar sign, not only in Mississippi, Alabama, North Carolina and South Carolina. We felt that it was certain infringement upon his rights. One there was another feeling and that second feeling was that the time was here and now for black people to quit being afraid.

I was determined as an individual that I should not be dual standards of behavior, one standard for whites and one standard for blacks. If it meant and we had known before that in nonviolent situations we are the victims of violence. Right now we must go down to Mississippi and we must let people know that they cannot back up now. We now have the Congress on Hill studying the Civil Rights Act, they cannot back up. They must continue to demand and even at the risk of being hurt they would certainly have to keep on moving and that was the thrust that we had as far as coal was concerned. Okay, I know a number of leaders from different civil rights groups came together in the Lorraine Motel to discuss plans for the march. There seemed to be some issues that needed to be resolved in some disagreement. Can you describe what that was all about? Yes, first of all we were trying to get up a manifesto purpose for the march and growing

out of the meeting each organization had some aims and objectives to put forth. Some wanted to narrow the focus of the march. Some organizations did not want to march. Some felt that the march marching was complete with the Selmer march. Some felt that we should go on with the march. Some felt that we should now broaden our scope for the march. These various issues led to an agreement which was called a manifesto which would be used as a purpose for stating our purpose and objectives of the march which later led to some confusion among the civil rights organizations.

I know that a couple of organizations withdrew and I understand what the reasons were that they withdrew. NAACP, Irving League, I know it pulled out. Well the NAACP, well there were a number of groups and individuals at the NAACP that was Medgar Everest, Medgar Everest brother, that is Charles Edwards, and individuals, Whitney Young represented the Urban League was there, like while Stokeley Carmichael of Student Non-Valley, coordinator committee, I think he had just recently been elected. I know it was in the room but I know there was disagreement trying to get what they disagreed about. They disagreed about aims and objectives of the march. My point and of course the core point was that we should march and that we should ask far more than was asked than the March or Washington.

Now as for one I always felt that the March or Washington we never asked for enough and our demands and the threat of the movement had stopped short and here was the time where our ideas should be broadened. I felt that one of the major problems that black people had, even if we had a civil rights bill and a civil rights bill, were then being had and some had passed, even then if you didn't have the right to, if you didn't have the money to register at a holiday in what good was the right to live at a holiday in if you didn't have the money. Basically the entire American system was an economic system, politics was totally economics and economics was totally politics, you cannot divide them. I think the great French writer who came over here and all of the others have simply said we are an economic system and until we could participate in the system and that would be and then from an economic standpoint all the way that would then we would be accomplishing

something. Second point of it, one psychologically blacks had been told to be subservient, to fear, to do what white people said and this would have to be attack and March on Washington did not deal with this. We were trying to reach too much common ground and not a lot of substantive ground that would carry us into the areas where the masses of black people needed to be elevated and one of the things that the marches would do were to unify, to bring about a broader political base, to get people to register in vote and likewise to demand a freedom bill of rights which was at that time being advocated by the A. Phil Brandoff Institute by Bob Ruster. Okay, let's stop down there when checking where we are in this room. Mark it please. Okay, 10, 23 camera roll.

Okay, explain to me why this was march of common people. The murder march different from all other marches following reasons. One, most of the other marches had been in urban settings. This march was in a rural setting. This march different because you had, it was not as organized as the other marches. It was not the logistics of the marches, was came into play on the basis of the common people. There were many who joined the march who did not believe in nonviolence. There were those that believed in nonviolence but there were far more people that believed in violence and nonviolence on the march and it became a policy statement and policy issue as to what kind of statement we would issue.

And of course our statement was that we believed in nonviolence. But the people that were now joining the marches were people of all phrase of life. Little people, big people, not just organized clergymen, not just organized racial groups, not just organized pacifists but here people were coming in from all over the area to join the march. Therefore, it was my position that all of the people should march. All of the people had fears and these people would have to march and let people know they were no longer be afraid. That was the central point of the march and at the same time that we would build up a political base by getting these people to register and vote. Now you remember when the march got to Batesville, when the march got to Batesville, here we had created a number of people, had created an influence among the people. We had no food.

We had the organizations that had not given us the money as before. But somehow another we got food. When we got to the churches, food was there, people knew we were coming and it sort of like Christ's feet in the multitude on this march. The reality of it was that we sent word out of the direction that we were coming and somehow another when we got there, we had what we needed, even though we had not the money that the other people had. It was a really rinky dink march that was organized by the common people and not basically the civil rights leaders because most, I was the only leader who was on the march every single day and most of the other leaders moved in and moved out. But core and its logistics that was handled by Herb Calendar, SCLC had other representatives out. But we were the ones who really had to move through Mississippi with the will and the heart of the people and they came out and brought us food, clothing and everything else that

was needed to make the trip possible. I know it was an entire family affair, but in the physics, I wonder if you can just tell me what it was like taking your entire family on that march. Well after I got on the march, I called home and I think it was my son and my daughter asked to come down and then they talked and then a few minutes later they said they all wanted to come down and I said, well come on. Of course it was not the first time that all of my family had marched with me. We had marched together in North Carolina and even my mother, my wife was pregnant at the time that she marched on many of the demonstrations earlier. So it was nothing new for any of us in our family. My oldest daughter, Jocelyn has been arrested for more times than I have in marches and demonstrations. So they all came and we had a lot of fun, marching, meeting people, singing, going into people's home, following the blues trends and making our notes and coming back over

the blues route. We knew route 51, first hand and we came all the way down until they came all the way down up until we got to Jackson on that Sunday. Now there were some vials along the way and you didn't have the federal government that would protect you as they had been on the summer march, for instance. What are you worried about your family? Well you always worry about your family. But yet these were the days when I think you love your family and you know that it's possible something's going to happen and things did happen on the march, many of which were recorded and many of which were not recorded. But you have to take a positive look on it. I didn't want my kids to ever go back and say they did not participate in something. They asked to participate and I felt it would be wrong if I were down here marching in

the street to tell them that they could not march. And if my wife was coming along after I certainly knew that she was well experienced and she would keep them pretty much in hand. So that did not pose too much of a question. We had had that kind of experience in North Carolina. Now of course you were a fairly new leader for CORE and so was Stopy Carmichael and Dr. King also spoken by the mass rallies. Was there any sense of competition among the three of you when you spoke at the rallies that in those nights? I think that that wasn't in a sense of competition as far as I was concerned. I think that the movement itself had previously been an adult movement. The NAACP had been the dominant organization and I think that from the NAACP out came the Congress of racially quality and the urban league had always been as I said that urban

had had function in an urban setting. But in a rural setting now and as a result of the young people since the sixties the young people had come into CORE, the NAACP and I think it was more of a youth movement in all of the organizations asserting themselves far more than it was competition among leaders themselves. It was a clash of ideas, no question about a class of ideas. I said earlier that Biod Rustin had said that he would not come down on the march because our objectives were not clearly defined. And my answer to that was how can our objectives be clearly defined when the circumstances we live under as minorities do not permit us to totally define the problem.

We must move when the least of us are affected and we must move because those of us at the top have that sense of responsibility to move. So when we would go to public meetings and mass meetings I think each group would probably emphasize one point more than the other. I think that there was always a thrust on the part of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to always emphasize that this is what Christ would do, that Christ too was a warrior and was a fighter. And I think core would always say it's black and white together. That was a theme that core carried out and that we believe likewise in self-determination. And I think the stick people carried out certainly the continuation of what we both said but at the same time a form of more radicalism.

Now to, there were other organizations on the march too now. We have 90 things in the market. The Deacons for Justice and Defense came out of Louisiana. We had been in Bogalusia together and it was a group that formed to protect the marches from attacks when the law enforcement officers would not respond. And when we got on the march, the Deacons for Justice and Defense came there and they were armed. And the question was are we going to tell the Deacons to go home? And someone said they basically grew out of core organization and community organizations in Mississippi. You tell them to go home. I said no. I refuse to tell them to go home. I think they have a right to be on the march. I think we should tell them, as we tell everybody else, that we believe in nonviolence. But I'll not tell these people to go home because they have a right to be here and protect

themselves as other people. In other words, I don't believe in a standard for white and a standard for black. I think that violence and nonviolence is equally distributed among all races. Okay. Let's stop right there and change rules. Okay. Okay. After, Stokely used the term black power in the speech at Greenwood. There's a lot of discussion about it. How did you feel about black power? What did it mean to you? Well, I like the expression. And that was not the first time it's been used. One of the first time that Stokely had used it, I'd use expression. I think many, many people had used it. I think Du Bois, Richard Wright certainly had used it. The expression of black people getting their power. I think it was really, it scared people because they did not understand they could not subtract violence from power. They could only see power as a violent instrument, a company in it.

But when Stokely is at Greenwood, I think, and every night just about the expression was used in the last analysis, it was a question of how black power would be defined. And it was never really defined. We talked in core about constructive militancy as black power. And we defined black power as having six salient points. One of those points that we emphasized, and we even emphasized on the march. As we would march, we would give the African craft for freedom. And many people were disturbed because they said this is becoming too much non-American. We are talking more, we are going back to our roots too much and these kinds of thoughts were being.

And Snick was talking about nationalism at that time. These were some of the fuzzy parts of the march, of which some of the other national organizations objected to. And some of the mine of organizations, like Ron Karinga from California, coming in. And this was also an emergent, solidist march, emerged at Black Panthers, the leadership that was coming in, were using so many new expressions. And of course, black power was the one that got the fancy of the press. And tell me about how you were injured in the camp. On Canton, Mississippi that night, we went on to that better debate about which school ground to use. And we finally said, we were going to the black school ground. And we went to the black school ground. And we had no knowledge that we would be denied the use of the segregated school ground. And when we got there, we found all of the Mississippi State troopers armed and lined up. I was on the top of a six wheeler, 18 wheeler, I should say.

And the leaders were speaking from that platform that night. And as we started speaking, the tear gas callisters started flying around us and one hit me on my knee. And I fell from the top to the ground, and that's where I heard a crack and my disc had gone out of place. In spite of that, we went on to the march and went on through to Jackson on the following Sunday. But Canton was a scene where I think stokely was gassed, it was gassed severely. But the two of us, I think, suffered more than anyone else except the populace from the gas that was put out there. When you finally got to Jackson, what were your feelings about that time? There have been a lot of discussion, a lot of debate and discontent, in some cases, along the way. Did you feel there was any future for unity in the civil rights movement or any sense of accomplishment?

Where did you feel? Well, as I felt more like a parent or a middleman when we got to Jackson, my mind was firmly made up. I've always lived in the South and never wanted to really be an urbanized northern man. I knew that the roots to any movement was in the South. Secondly, I knew that the change would have to come from the South and move northward. Thirdly, I knew that what we had been doing, we could no longer do. Our growth had grown and the populace that we were serving were now making more demands out of us rather than having ceremonial, counterlight marches. That march itself had served this purpose and we had received casualties.

But somehow, another in the future, we were going to have to deal with the economics of the black man. When I made my speech in Canton, I mean in Jackson, I spoke to those various issues, although my speech was not recorded, I think that by the time that I got to the mic, the press wanted to hear what Dr. King had to say. And unfortunately, because they really wanted to hear what one man had to say, they miss so much of the total philosophy that was being carried on that would have educated white America that we spent decades trying to eradicate that and trying to resolve the meaning, the true meaning of black power and the directions that the movement would go. I want to backtrack just a little bit because there were one of the big issues in the march with the role of white people, whether white people should even be involved in the

march. Can you talk to that? The Congress of Racial Equality has always felt that white persons should have been involved in the movement. America is his made up of black and whites. One of the things that we've always felt in the Congress of Racial Equality, the Congress of Racial Equality, was having strong demands being made, of course, for more power in the hands of black, even within the organizations, and many of the whites in the organizations felt threatened. But many and many left because of that. On the other hand, many stayed. And as I'm feeling that whites and blacks should always be together and all things, that's still our position. I think the murder of March, as I said, was made up of all kinds of people. This was the first time I think on any march that I've been on where you had people, pacifists,

you had all religions represented. We were at all churches. You had people who believed in self-defense. You had people who believed in nonviolence. And you had people who philosophically believed in nonviolence, but believed in violence. And I think the entire mode, a mood that the march wanted to carry to the public was that, and the organizations wanted to carry it out, was that the march itself was a nonviolent march. But we in reality knew what was on the march. It's just the same as if I've been in the army, and I was in army four years, and I cared weapons on this march. I cared no weapons, and I believed in nonviolence. But I knew what was on that march.

Okay. Let's stand down there, and then, how much? Market? Okay. Give us your own question. It was quite odd that when we, each town that we went in, we would tell the people that we were there to help them, that we didn't have any money. And the march was not funded, not like the other marches. And we would tell them where we would go to the next night, like we're going to be in Inabina, Mississippi. And that when we got there, we heard the two blue singers were down there, and we wanted to see them, and everybody could eat fried chicken and beans. And somehow another, when we got to Inabina, everything was organized without our having to put out any money. And one of the strangest things about this, which made it a common denominator march, was the fact that we had little children marching with us, children who left school who saw

the importance of the march, children who were inspired by the march, who sought souvenirs to meet persons on the march, and children who were told what voting meant. The Freedom Schools in Mississippi had paid off, and as we marched through Mississippi, no one was, you'd be surprising how many would meet us in the middle of the day with foods. It was easy to find a drink of lemonade along the route, and yet we had never asked for the lemonade. We had never asked for these things. And whenever we got to a church, the night before, was 24 hours notice, yet we were marching through the most poverty-stricken regions of the nation. All right. Thank you very much. Very nice. All right. We'll open up thresholds. Okay. You were saying one of the problems of the Meredith march took from you? Yeah.

The irony of the Meredith march is that we had to place your rates. In other words, we were forced to carry a posture of non-violence, yet when we went in the community and had every public meeting, we had as many people who believed in violence and who would say, I'll give you my money and I'll give you my food, but I can't agree with the posture of non-violence. That was the reality that we faced. I felt that the time was that a movement is made up of all people. But our community is based upon sane people and sane people. People like colored, black colored purple, you know. And we could no longer demand a philosophy of a man who had a common aspiration to share

in a constitution of the United States, in particular when he would be called upon to go to a war in Vietnam to give his life and be required and be taught a violent posture. I'm going to change the subject completely and go to the Association of Hill Browns Bill's situation and ask you for a course position on the community control schools. What's first, in a school in a community, should have parents of the teachers and the community leaders involved in the program and the curriculum, so that children could be taught and be the products to live and be educated to compete in the society. That they were about to compete in, upon graduation to compete in.

We believe that the boards, which many times had been exclusively white in certain communities, should now open up. We believe that the curriculum should change. We believe that all students should be exposed to black history, for example. We believe that trades and what was taught at certain courses being taught at predominantly black schools, black kids were being created to go into the workforce without getting liberal arts education. We believe that these communities, once they had control of the schools, that the quality of education would be improved and the products of the schools would be able to compete in American society.

- Series

- Eyes on the Prize II

- Raw Footage

- Interview with Floyd McKissick

- Producing Organization

- Blackside, Inc.

- Contributing Organization

- Film and Media Archive, Washington University in St. Louis (St. Louis, Missouri)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip-75d37b02169

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip-75d37b02169).

- Description

- Raw Footage Description

- Interview with Floyd McKissick conducted by Blackside for Eyes on the Prize II. Discussion centers in which he talks about the Meredith March and the more aggressive young activists within the various Civil Rights organizations. He challenges Bayard Rustin's claim that the march lacked clear objectives. McKissick also addresses the controversy regarding the participation of the Deacons for Defense and Justice, whose members carried weapons. Other topics of discussion include, the slogan "Black Power," a Meredith March rally in Canton, Mississippi, a speech in Jackson delivered by Martin Luther King, Jr., economic issues, White participation in the movement, and CORE's position on education.

- Created Date

- 1988-10-21

- Asset type

- Raw Footage

- Topics

- Race and Ethnicity

- Subjects

- Race and society

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:33:53;14

- Credits

-

-

:

Interviewee: McKissick, Floyd B. (Floyd Bixler), 1922-1991

Interviewer: DeVinney, James A.

Producing Organization: Blackside, Inc.

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

Film & Media Archive, Washington University in St. Louis

Identifier: cpb-aacip-71f85263bca (Filename)

Format: 1/4 inch videotape

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “Eyes on the Prize II; Interview with Floyd McKissick,” 1988-10-21, Film and Media Archive, Washington University in St. Louis, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed July 2, 2025, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-75d37b02169.

- MLA: “Eyes on the Prize II; Interview with Floyd McKissick.” 1988-10-21. Film and Media Archive, Washington University in St. Louis, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. July 2, 2025. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-75d37b02169>.

- APA: Eyes on the Prize II; Interview with Floyd McKissick. Boston, MA: Film and Media Archive, Washington University in St. Louis, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-75d37b02169