The Criminal Man; 2; The Born Criminal

- Transcript

Is criminal behavior hereditary? Is there a born criminal? These and similar questions today perplex society. Here are some of the answers. The Criminal Man, the series of television studies of the nature and patterns of criminality and of the causes and cures for criminal behavior. Our guide in the study of the criminal man is Dr. Douglas M. Kelly, professor of criminology at the University of California. This program will be the first of two devoted to the relationship of heredity to crime. It is subtitled The Born Criminal. This man could probably get a job in Hollywood playing the role of a criminal. His facial characteristics qualify him for what are commonly but mistakenly call the criminal type.

Actually, there's no such thing as a criminal type and there's no such thing as a born criminal. Unfortunately, a great many people, however, falsely believed in this kind of folklore and many times throughout the country. People are turned down in jobs because they look like a criminal or juries will say he has criminal features. Actually, the idea of a criminal type is simply folklore, but the belief is widespread. And I wonder how many times a day scenes like this occur across the country. If I've ever seen a guilty person, he's one. What do you suppose he can? I don't know, but it could have been almost anything from the looks of him stealing murder, rape. I wouldn't want to meet up with him in a dark alley. Maybe we're jumping to conclusion. No, just look at him and you can tell he's the criminal type. Look how deep-set his eyes are and how close together.

Look at his oily hair and thick lips. Those are the signs. He looks like a criminal. He's guilty, all right. I knew what had happened. Sooner or later, I knew what had happened. You knew what would happen. A teenager down the street. He was in some kind of trouble last night, an accident with his car. I knew the cops would get on him sooner or later. How can you say that? But didn't you know? His father was a jailbird. He spent a lot of time in prison. That kid's got his father's blood, that chip off the old block. A born criminal. Criminality handed down through the blood. That's like saying the world is flat. These vignettes you've just seen were, of course, fiction. But a fiction based on fact. As a matter of fact, this belief is very commonly held all throughout the country. Individuals are very frequently considered by juries and others.

As being guilty, simply because they have the so-called criminal features. Already hair. Six close eyes, perhaps are left handed. And again, another thing, which is probably just as bad, is the notion that a person isn't guilty because he doesn't happen to possess those criminal characteristics that we think make a criminal. You can't tell by looking. And criminals are not born. These, I think, are two considerations of beliefs that the American public have. And it's based primarily upon first folklore and secondly of belief in stereotypes. The stereotype belief you can tell by looking is perhaps the most common. Well, I'm sure that you are probably familiar with the stereotypes. I'd like to show you some samples.

For this particular experiment, we arranged to have some artists portray all unknowing to each other, of course. Their idea of the typical Hollywood criminal. And if you look at these pictures you'll find that while they're all different, they have certain things very much in common. For example, each one has the deep set generally close together eyes. And the eyes in each case tend to be sunk deep within the head. And then the foreads in many of these are small and narrow. And you have in each one the large nose, sort of a quilla or eagle-like nose. And then the large predominant or thrust out jaw. And if you want samples of this kind of thing, of course, you don't have to have an artist paint them. All you need to do is to go out to the nearest store and buy yourself a whole set of pocketbooks.

If you'll thumb through them in no time at all, you'll be able to find a half a dozen published perhaps by different companies about different things and yet with identical types of faces on the cover. Again, this stereotype of the so-called criminal man. Now many of these things that we call criminal characteristics are hereditary. And this is the reason, of course, for some of the belief in hereditary criminality. We'll talk about that in just a minute. But first, let's consider the characteristics themselves. Where did they come from? Where did we get the idea of the criminal type? Most of it stems from this book. A book by Cesar Lambroso entitled Criminal Man. Cesar Lambroso was an Italian psychiatrist who did his work around the turn of the century.

Lambroso worked primarily in a mental hospital in Italy for the insane criminal. And as he worked, he became interested in a facet of the then popular phase of psychiatry dealing with physical characteristics in relation to abnormal mental patterns. One day, while he was doing an autopsy, he reports, he saw a skull, the skull of a criminal. And he says, at the sight of that skull, I seem to see all of a sudden lighted up as on a vast plane under a flaming sky, the problem of the nature of the criminal. An altivistic being who reproduces in his person the ferocious instincts of primitive humanity and inferior animals. Beginning with this idea, the criminals were altivisms. Throwbacks to earlier types of primitive men and animals, Lambroso studied criminals. And he then reported various physical features, for example, the nose. This is frequently twisted or flattened in thieves.

In murderers on the contrary, it is often equivalent, like the beak of a bird of prey. The ears, the ears are of large size. Occasionally, they're also smaller. This seems like a reasonable idea. 28% of the criminals he found have handled shaped ears, standing out from their heads. In others, the ears are pointed, like the ear of the devil. Then, when he studied the mouth, the mouth shows many anomalies. For example, the lips may be thick and protruded. And over and over again, we get the appearance of the prognathic or stuck out jaw. Of course, in some criminals, he didn't find this, so he added a second type, the weak or receding chin or jaw. The eyes come in for considerable discussion. And here we find the origin, perhaps, of the narrow eye, two eyes which are set close together, narrow between the bridge of the nose, or the so-called shift-di, a pattern which is hung on in our culture ever since.

He also has any number of other descriptions. For example, the presence of hair, abnormal hair, or, oddly enough, in some cases, two little hair. As you can see what Lambroso generally was doing, his Lambroso was describing his patients, a select group, the insane criminal, and generalizing from these few to the many. He also focused upon the anthropoid or ape-like appearance of people generally. For example, in his description of the hands, he points out that the hands are longer. The arms are longer, and when the man walks his hand will swing below his knees as doesn't hate. We know today, of course, that Lambroso's theories were pretty wrong. We know that his thinking about atheistic signs of criminality were not in the right path.

But I don't think that we should ridicule Lambroso, because after all, Lambroso did the best he could with the tools at hand and the theories then available. Basically, what Lambroso has contributed was to focus on the criminal away from the crime, while the path he took towards physical features happened to be the wrong one. He left the legacy whereby, on focusing on the criminal, we now concentrate on the psychiatric, the psychological, and the individual sociologic factors which make up modern criminal logical theory. And so, we all, Lambroso, would tremend this debt in giving us this focus. Since he was so intelligent, of course, the question comes up, how did he manage to get so far field? And here you have to understand a little bit about the time in which he worked.

You must remember that when Lambroso's theories were formulated at the end of the 1800s, most scientists were primarily interested in the Darwinian theory of evolution. Most of us, most scientists in those days believed, generally, as apparently Lambroso did completely, that you evolved as an ape and then suddenly in some mysterious way sprang over to become a human being. It seemed reasonably, then, that after the human being was a higher process than the ape, the more human being, in his skull and bone structure, looked like an ape, the more brutish or ape-like he'd become in his interpersonal behavior. And so, Lambroso read in to the faces of his criminals, ape-like characteristics, and he seized upon the hollow eye sockets, and he seized particularly upon the snout-like appearance of a simian skull, the long-Lord jaw, and particularly the protruding high cheekbones. And Lambroso postulated that if an ape looked like a human, or a human looked like an ape, this was obvious evidence of atheistic or ape-like characteristics, and he would behave like one.

Of course, we know that's not true today. Lambroso worked generally along the theory prevalent during that era, that you started with an ape, and that eventually the ape became human, and somewhere in between was a missing link. Actually, of course, we know today this isn't true. We believe that fundamentally, way back somewhere, eons of go and the origin of man, there exists a primal type from when spraying on the one hand man, and on the other hand, the ape pattern. And that as man developed, slowly but definitely, there is no specific interrelationship between ape and man, and that if man happens through coincidence to have characteristics which simulate the ape, there's nothing to indicate that he's going necessarily to become ape-ish. Of course, there are other features, which are hereditary, besides the features of the face, and many people think that criminality is one of these.

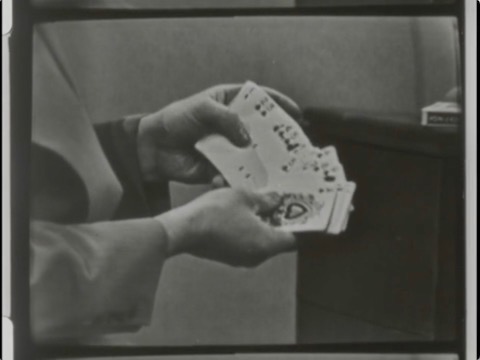

In order to understand this point, we have to talk a little bit, I think, about the problem of inherited characteristics, genetics. I don't plan to give you a lecture on genetics, but I think I can demonstrate two or three important points. If we take a deck of cards, we can compare them with, let us say, the chromosomes. A great many people, erroneously, seem to believe that you inherit half your characteristics from your father, half from your mother, quarter from your granddad, quarter from your grandmother, quarter from the other, eight from the great grandparents, 64 from the grandson up. Now, I think it's essential to realize that you don't necessarily do this. If we take the cards, for example, and let the suits represent the various chromosomal divisions, actually, we'd have 48 cards then. I think we can consider the fact that these represent the father's side. Let's take the black ones, and these represent the mother's side.

Now, if a child inherited 48 chromosomes from each parent, naturally, he would have 96, so that actually what takes place is the chromosomes split. Chromosomes are passed down in pairs, and you may get, say, the Asa Spades, and the Asa Hearts, or the Asa Spades, and the Asa Diamonds. But if you get the Asa Diamonds, then you won't get the Asa Hearts. If we look at it from this viewpoint then, we suddenly realize that the individual, the child, receives his gene pairs from two grandparents, but not from all four. Now, if the Asa Spades is considered to be, let us say, horse thiefness. Granddad was a horse thief. It's pretty good chance that you might inherit the club factor, and the horse thiefness would die with Granddad. Also, of course, the distribution is pretty random. And if we shuffle up our cards, as apparently our genes are shuffled up in the chromosomes in real life, we may get a completely random distribution.

Now, remember, we've been talking about 48 chromosomes, apparently, with one gene to the chromosome. Actually, there are tens of thousands, so the mathematical potentialities are unlimited. But with the result that no human being exists with the same identical features of the other. Then, too, if we equate some of the problems of statistics, it's quite possible that, let us say, all the black chromosomes would stay on one side, leaving us with all the red ones for the other. It is reasonably feasibly, statistically, to feel that perhaps you might inherit all the genes from one grandparent and none from the horse thiefness. I stress this point because so many people seem to believe that you inherit these things directly.

Actually, the last example would be very rare, statistically, but it could happen. And what it indicates is that inheritance is they have hazard pattern. Over a period of generations, the chances are pretty good. You don't have any particular genes of your great, great, great, great ancestors. But we've talked about horse thiefness as if it were hereditary. Actually, it's an acquired behavior pattern. And acquired patterns are never transmitted through genetic patterns. It would be just as reasonable to assume that if you tattoo a horse on your granddad's chest, you might be born with such a tattoo. As to assume that if your granddad was a horse thief, you might inherit your granddad's horse thief-like behavior. Of course, you do inherit certain things. If we take any good text on heredity, we'll find that some of the most common facets inheritance are the bony structures. Not just the facies, the head shape, its size, but also the ribcage, the arm structures, and particularly the length and strength of the total skeleton.

The entire constitution or body build probably is inherited. Then if we take a look in the table of contents of any standard text, we'll find many other hereditary factors. For example, we'll find inheritance of skin color, obviously eye color and hair color. But there are many, many other things. The blood groups are obviously hereditary. You may have an extra finger or an extra toe. You may also inherit a number of disagreeable things from a medical point of view, such as a tendency to bleed too much, the hemophiliac, or you may inherit some types of mental deficiency. As a matter of fact, obviously, you inherit all of your body tissues from someone of your grand parental or earlier structures. However, if we simply accept the fact of heredity, for all these features, do any of them have any interrelationship with crime? And the answer flatly is no. All textbooks are completely agreed that none of these characteristics incline toward criminality.

Of course, you must remember if your father is a criminal, you may grow up with these behavior patterns because you live with him. I'm always reminded in this instance of the story of the little boy who was being spanked. He was a fort his dad's knee and just as the hairbrush came down, a little fellow turned and said, stop. A lot of stopped and said, what do you want? A little boy said, dad, your father ever spank you? Well, of course he did, naturally. A little fellow said, great granddad ever spank granddad? Well, sure, I'm sure he did. A little fellow said, great, he says, dad, let's put an end to this hereditary brutality. This sort of thing is, I think, typical of the thinking of many people because it happened to the father and because the child imitates it in the identification mechanism, then it's pointed out as hereditary.

Actually, all of the things contained in a text of this type are definitely not related in any way to criminal behavior. Not all of the things, of course, that we consider in criminal behavior came directly from Lambroso. It's a great deal of folklore which has come from other sources. For example, if you read the old Greek texts, you'll find that descriptions of ancient Greek criminals with physiognomies, with makeup patterns, very similar to Lambrosi in theory. Lambroso himself, in his textbook, quote, several French proverbs, beware the man with a shifty eye. And if you read Shakespeare, you'll find it simply crammed with examples of persons who are criminals with apparent physical characteristics.

For these reasons, people still believe in this folklore pattern that red-headedness, narrow-eyedness, pointed-earedness, and left-handedness show criminal potentiality. Actually, we'll discuss this for these particular problems in a coming session of our discussion. And I'd like, however, for now to wipe out another misconception, the fact that a child who has these patterns necessarily must grow up to be a criminal. We must realize that there is no relationship between facial structure, between hand-edness and hairedness, between any of these hereditary factors and murder, rape, larceny, or any other kind of crime. But if a child is born with some of these characteristics, or if the child acquires through some kind of deformity pattern, I think it's important to realize that perhaps he may become a criminal and be apprehended partly as a result of the deformity.

The reason for this is that it's what I like to call second-hand criminality. The deformity itself doesn't produce it, but the cultural attitude to the deformity upsets the child so that he reacts against the culture. For example, if a person is a small-body-build, that's heredity. And if he grows in a culture where everybody points to him as a little man, someday working under the theory of adlerian inferiority, he may become upset. He may blow up and violently offend the society. Now you can't say that the hereditary factor of his small-body-build was directly related to the crime, but in a second-hand way it was. The body-build is heredity. The cultural attitude, however, is what produces the crime. And for this reason, I think it's essential. The children who are born with any of these so-called criminal characteristics should be educated early in life by their parents to the general idea that they are not going to grow up as criminals.

I think further it's essential to educate people into an acceptance of variant types of physical structure. Some of us are big, some of us are little, some of us have narrow eyes, some of us have wide ones. And I think education early in life for our children on an acceptance of variant potentialities would do a great deal to rid us of this folklore belief which hampers our function in many areas. Then too, I think it's also essential that if a child has a criminal in the family, if the father or the grandad has been in prison, it's extremely important for the child to be educated that this is not an hereditary pattern. Children early can be easily taught that heredity does not affect criminality. Criminality does not run in the blood. And a child so prepared will then be ready and able to face the potential taunts of his playmates who may point out, but your dad's in prison.

And if a child has been well educated, he can withstand this onslaught and not follow along the line, not through heredity, but through cultural pressure. Let's take a look at some real criminals now just to see whether or not these criminal characteristics are obvious. Here, for example, is a nice young man, clean cut fellow. As you can see, he's wanted as a matter of fact, he's been badly wanted. He's one of the top 10 FBI's and he, while he is a pretty good looking boy, is really only wanted for burglary and robbery and escape and murder. Here's a chap who could be pertinent or anybody's dad, nice looking fellow, wanted for homicide.

Here's a youngster who could easily pass for an office boy, a fairly clean cut land. He's simply wanted for a number of serious crimes. Obviously, you can't tell by looking. In order to make this point a little more clear, we set up some pictures of some of the FBI's most wanted men. The FBI, of course, postes roundabout and has done wondrous well in catching wanted criminals with this technique. In this group of wanted men, however, we've also added a few of our own colleagues, some of our electricians and floormen. I wish you'd have a look at this group and see if by careful observation of the criminal characteristics, you can tell which one of the group are the electrician and floormen and who are the genuinely wanted criminals. Of course, you can't tell because as we pointed out over and over again, you can't tell by looking.

There is no possible way to pick out from those photographs. Don't let the type of photograph fool you. The type of person who basically is the criminal wanted by the FBI. This is the lesson that I think we must learn. This is the lesson that I think we must teach our children. That there is no such thing as a criminal characteristic. There is, of course, no such thing as Lambroso's theoretical activism. Individuals who are humans are humans, and the fact they have occasional characteristics, which are also found in the great apes, don't necessarily make them a criminal. Remember, there's no such thing as a criminal type. Remember, there's no such thing as a born criminal. And all by the way, this fellow we were looking at when we first began this discussion.

Our typical Hollywood criminal. Actually, this chap is a well-known local newspaper photographer. He's a church-going man, a loving father, owns his own home, has five beautiful children, a swell guy. The criminal man, the study of the nature and patterns of criminality, and of the causes and cures for crime. Your guide for this study is Dr. Douglas M. Kelly, psychiatrist, police consultant, and professor of criminology at the University of California. Appearing in the cast for this program, where Betty Tartal, Robert Schreiber, Bobby Lyons, and Poole, Alan Lowe, Harold Josephs. This is National Educational Television.

- Series

- The Criminal Man

- Episode Number

- 2

- Episode

- The Born Criminal

- Producing Organization

- KQED-TV (Television station : San Francisco, Calif.)

- Contributing Organization

- Library of Congress (Washington, District of Columbia)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip-512-td9n29q77k

- NOLA Code

- CMLM

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip-512-td9n29q77k).

- Description

- Episode Description

- Dr. Kelley begins to explore the myths that surround criminality, i.e., that inherited physical characteristics are a cause or recognizable symbol of crime. The fallacies in Lombrosos old theories are exploded. The theory of atavism is debunked, as are the ideas of stereotypes. Dr. Kelley concludes by pointing out You cant tell a criminal by looking. (Description adapted from documents in the NET Microfiche)

- Series Description

- The Criminal Man is a definitive study of the cause, prevention and treatment of crime by the late Dr. Douglas M. Kelley, police consultant, psychiatrist and professor of criminology at the University of California. The series, which takes its title from Lombrosos original work in the last century, incorporates a great number of dramatic re-enactments using highly skilled actors and films as illustrations. Dr. Kelley uses the first six episodes to define crime and criminals and to destroy the myth, folklore and common superstitions which have long surrounded crime. The second group of episodes analyzes the true causes of crime and posts guides to the prevention of these causes. The two final episodes look at current penal policies and their weaknesses regarding rehabilitation. Dr. Kelley indicates the lines of penological progress which he thinks would provide the greatest benefit to society. The 20 half-hour episodes that comprise this series were originally recorded on videotape. Dr. Douglas M. Kelley, police consultant, psychiatrist and professor of criminology at the University of California, gained national reputation as a brilliant theoretical and practical criminologist at the time of his work as consulting psychiatrist at the Nuremberg Trials. The public also remembers his testimony in the Stephanie Bryant kidnap-murder case. Dr. Kelley was a Rockefeller Fellow at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, and at that time (1940-41), he compiled clinical contributions for Dr. Bruno Klopfers book, The Rorschach Technique. His studies at the University of California led to his receiving and AB in 1933, his MD in 1937 and to his residency in psychiatry from 1937 to 1938. he studied also at Columbia University. He was married in 1940 and was the father of three children. During World War II he was a lieutenant colonel. (Description adapted from documents in the NET Microfiche)

- Broadcast Date

- 1958

- Asset type

- Episode

- Rights

- Published Work: This work was offered for sale and/or rent in 1960.

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:30:12.792

- Credits

-

-

Host: Kelley, Douglas M.

Producing Organization: KQED-TV (Television station : San Francisco, Calif.)

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

Library of Congress

Identifier: cpb-aacip-fb457bce274 (Filename)

Format: 16mm film

Generation: Copy: Access

Color: B&W

-

Indiana University Libraries Moving Image Archive

Identifier: cpb-aacip-97e4e781e79 (Filename)

Format: 16mm film

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “The Criminal Man; 2; The Born Criminal,” 1958, Library of Congress, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed July 16, 2025, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-512-td9n29q77k.

- MLA: “The Criminal Man; 2; The Born Criminal.” 1958. Library of Congress, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. July 16, 2025. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-512-td9n29q77k>.

- APA: The Criminal Man; 2; The Born Criminal. Boston, MA: Library of Congress, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-512-td9n29q77k