Thirty Minutes With…; Allen Ellender

- Transcript

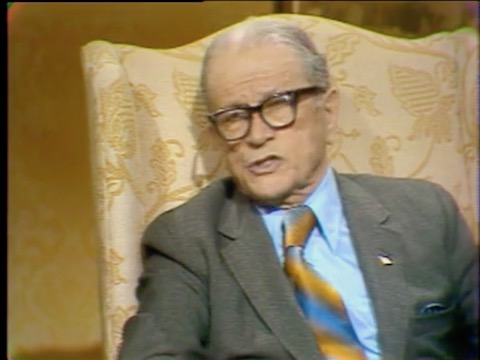

30 minutes with Alan J. Ellender, Democratic Senator from Louisiana, chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee, and Elizabeth Drew. Senator Ellender is the new chairman of the Appropriations Committee. You're now one of the most powerful people in Washington, so it's important to know where you stand on some key issues. First I'd like to talk to you about defense spending. What is your view of the amount of money that we're spending on defense these days? Well we're spending in my book entirely too much. It's my belief that we could cut back and get enough security with less dollars spent. And what I'm trying to do is to make the defense department justify every dollar they ask for, and it takes a long time to sit around and do that.

And I've always been willing to do it, and I have been busy all this week in hearing first the Air Force, and today I heard the Army and tomorrow the Navy. And the amounts requested are simply astronomical. Astronomical? Yes, in size. Now the budget for the defense is about, it takes 34% of our entire budget, or in dollars, it means about almost 7 to 7 billion dollars. And that's of course to pay for the support of the Army, the Air Force, the Navy, support all of the hardware they use, and also the board and lodging, if you call it that way.

In fact, all expenses connected with the military. Well, when you say it's astronomical or it's too high, where do you think it should be cut? Well, it strikes me that we could do with fewer soldiers. For instance, there's no reason why we should remain in Europe as we have been for the past twenty-two or three years now. You are for reducing the troops to NATO? Yes, indeed. I've been advocating that now for about fifteen years. In fact, ever since my first visit there, and it strikes me that Europe is now well able to take care of itself. And with all of that, however, we have about the same number of troops there we had twenty years ago, twenty-five years ago.

And Europe is financially well off. All of the countries we're assisting can well take care of their share. And I've been insisting on that for a long time. And all I get from those to whom I speak is, well, we'll see about it. You mean at the Pentagon? Yes. We'll try to do it. As a matter of fact, the record was shown that ever since the First Defense Secretary was renamed, I asked, what can we expect our erstwhile allies in Western Europe to pay by wave assistance? Well, the answer is that we'll do our best. But when the next time comes, the same assessor that defense assistant, I mean secretary who told me that previous year, he also takes the same position. We'll do our best.

And that's all I've been hearing since the selection of secretary Johnson. Well, now you're in a position to do something about it. Are you going to try to cut funds for that? Well, I am. And I believe that we might be able to do that this year. Our defenses in Western Europe are taken care of mostly by us. We have that at the moment, about four and the third divisions. But we also maintain in this country a few divisions in order to send them there in case of emergency. And I made a trip 10 years ago to visit NATO countries. And I found that the NATO countries were not cooperating with us to the extent they should. What about other parts of the Pentagon budget or weapons?

Are there other places that you would like to make some cuts? Well, yes, I'd like to make some cuts in research. When I first came to Washington, 35 years ago almost, the government spent around a billion nine hundred million or two and a quarter billion in research and all departments. Today, the research bill is over $17 billion a year. And nobody can make me believe that with such a large expenditure of research funds, that there isn't duplication or there isn't waste. Each defense department, that is Navy, Army, their force, have their own research money and it's spent mostly out of house, that is, on the contract. And there's very little spent in house by the services themselves. Well, the research leads to the weapons, doesn't it? Yes.

But what they do, they get ideas from everybody. That sends an idea in, they look at it and well, they think that it would be useful to us in defense by the proceed and spend money in research on it. And it's very expensive. Now, for instance, we have a research done on, let's say, Obama. Well it may cost as much as two and a half billion dollars, simply to find out whether a Obama can be built, that will be better than the ones we now have. And after those bombers are besurged, after the prototype is made of them, then the question arises to how many we need and how many we should produce. And sometimes the amount necessary in order to provide what the Navy and the defense thinks we ought to have goes up in the billions, as much as nine to twelve billion dollars

just for that one weapon. And the same thing occurs in fact in all sorts of airplanes, in the submarines and all things we need. Now, why do you think this keeps happening that the Pentagon budget keeps going up and the pressures are there for the new weapons? Well, as I've often said, I believe that the defense department should take a better look into the possibilities of our potential enemy, as to whether or not we should spend that much in defense, in order to protect ourselves against our main enemy, that's Russia. That's contented for a long time, that we can't afford as a nation to spend the money, to protect the entire free world as against Russia.

Now, I don't want any part of communism. My apart communism, as much as anybody in this country. But there's no doubt in my own mind, but that communism has made some advances in Russia. It has given to the people of Russia a better way of life. And when I first visited there, I thought the system was bad. But after going there, two or three times after my first visit, I felt that there was progress being made towards, believe it or not, capitalism. In 1955, when I first went to Russia, I had a little trouble to get there. What do you mean? Well, the State Department didn't nightmen to go there, because I didn't know why at the time. Did they try to keep you from going? Well, they suggested that I'd lose my time by going there. There was no point in my visiting Russia or Moscow.

So I said, I want to go, because I visited every embassy in the world except the Moscow. And I said, I'd like to see what's going on there. And I want to see why it is that we can't be more friendly with Russia. So when I went there, when I got to Moscow, I asked Mr. Bolin, who was then the ambassador, as to whether or not he would permit me to make appointments with members of the Politburo. At first, I asked him if he had done it for me, because I had written him to make these appointments. And he said he wouldn't do it. He had strict instructions to make no appointments for me with any one in the Kremlin. So I asked that I be permitted myself to do it. So after sending a cable to Washington from Moscow, I was given a green light to proceed and make my own appointment. And I tried to use a telephone in Mr. Bolin's office to connect with the Foreign Office of Moscow.

And Mr. Bolin looked at me, he says, keep your hands off of that telephone. He said, I have instructions not to permit you to use anything, any telephone in my office knowing that in the embassy. And he dug down his pocket and gave me two coins. And he said to me, he said, go downstairs, there's a pay station there. And if you want to connect with the Foreign Office, you may do it that way. I've read your reports on your trips and they're very interesting. And I think it was quite early that you started saying that you were against the containment policy, really, of putting bases around the Soviet Union. Well, that's what I found out after my first visit. And that was the reason why I believe they didn't like me to go to Moscow. Because at that time, they had started this plan of isolating Russia. They started out by building airfields in Japan, Okinawa, the Philippines, Taiwan, all of North Africa, and all of Western Europe.

And that program cost us billions of dollars. And I wondered why it was done. And on my second visit to Russia, when I was able to go among the people, I was invariably asked, why did you build this ring of steel around us? What I said for protection, because that's what I thought was built for. And I was confessed that I did vote for some of these appropriations to build this ring of steel. But I didn't realize the purpose at the time. But when I found out the feeling of the Russian people, I felt it was built in Propaganda that we had for the leadership there, to be able to tell the people of Russia that we were trying to take a mobile. As a matter of fact, that wasn't true, but yet it was a real propaganda that the leaders could show to the people that we in America were trying to take over the Russians. Well, what about now?

You're in a stronger position than ever to affect our policy towards Russia. For instance, the anti-ballistic missile system, what's your position on that? Well, I voted against that. You're against it. Against anti-ballistic ABM, yes. Because I think it's silly for us to protect the weapons that we hope to shoot at Russia of the attackers. It's my position that if we should be attacked by Russia, they'll go all out against us. And they're not going to try to destroy our ballistic missiles in place, but they'll try to destroy our cities. Do you think that the administration is doing enough to get an arms limitation agreement with the Soviet Union? Well, it's my belief that we'll never get salt talks the way we want them. If we talk peace in one corner of the mouth and then prepare for war in the other, it doesn't make sense to me. It doesn't add up. And that's why I appeared sometime ago before members of the armed services, the Joint Chiefs of Staff and others, and I tried to argue with them and told them that it's my

belief that if we try to work with the Russian people, try to do something to whereby we could trade with them, whereby we could exchange ideas, exchange views, we could have an exchange program, that it might be better to do that and learn more about them than for us to keep on arming ourselves for a war, which in my opinion may never come. You've been critical, excuse me. And it's my belief that if we try to work with the Russian people, and without embracing that rotten philosophy, I don't want any part of that, it strikes me that we could get on better terms. And thereby do away with this preparation that's been going on now for 22 years. And there seems to be no end to it.

And if we can only make the Russian feel that we're trying to help in world peace, we ought to be able to get together and stop the expenditure of these huge sums of money. You've been against military assistance in general, I believe. I think that you said very early we shouldn't be sending military assistance to Vietnam or supporting the museum regime. Well I voted for the military assistance, and that is aid since 1952. I voted that was my last vote for it. That was a time that we had spent about $15 to $16 billion to revitalize the economy of Europe, and I thought that was enough. Now when we attempted to spread it all over the world, that's when I drew the line. And I got interested in traveling all over the world in order to visit the various places

where we had spent some of this money. And to say the least, I found a lot of waste here and there. And a lot of the money we spent, Mr. Target, it didn't go to, it didn't go to the benefit of the people who are trying to help, but in many, on many occasions to the politicians of the country. And I have never been against technical aid to system how to do things. But this idea of big grants in various fields without proper study. There's a lot more to cover. I want to ask you quickly about domestic spending. Do you, for instance, in the area of poverty, the poverty program, do you think more or less ought to be spent on that? Well, I think less could be spent and be more effective than the amount you're spending now, because in this poverty program, welfare program, there's no doubt in my own mind,

but that a lot of people are receiving much help that they're not entitled to. And there's no doubt, but there's duplication, triplication, and maybe they're quadrupling it in some cases, where the same person might receive from four different areas. Have you checked that out? Well, we've had it checked by Senator Berg from West Virginia here for the District of Columbia, and I have no doubt. But the same things that happen in the district, you could trace that to all the states of the Union. So, do you want to cut back in those areas? Well, I don't want to cut back so much as I want to see to it that those who are in need receive the aid and cut out those who don't need it. And if that were done, I believe that we could cut back our program by probably a third. The poverty program?

Well, welfare program. The welfare program. The welfare program, which of course embraces quite a few different programs. But if those programs are properly administered and the people who are entitled to receive them, if they're the ones who are paying them, I think we could cut the program by a third and do more good to the people in need. So, any place where you'd like to spend more money? Well, yes. I would like to see more money spent to protect and preserve our two most important resources. That's land and water. What about you've been for housing, legislation, and everything else? Yes, I've been. As a matter of fact, I was the author of the first public housing bill that was adopted by the Congress. And I'd like to see money spent in getting better housing for our people. Now, even in that field, you have some who get into the programs that are not entitled to it. But all in all, we ought to have better housing and we could do a lot in the educational field in order to help people.

And in that process, we ought to be able to spend money wisely and we ought to be able to make it possible for people who are now out of a job to be capable of- What's your position on the president's revenue sharing program? Well, we've been sharing revenues now for almost 150 years with the states. It started way back in 1789 when our government was twice organized. But he wants to do it differently. Are you going to be with them or opposed? Well, he doesn't want to do it differently. We've been sharing it, and now what I'd be willing to do is to raise the ante, as it were, as to the amount that we give the states in certain programs. For instance, you take the welfare program. On a no-condition, do I believe that the welfare program should be taken over by the federal government? I think it's a program that should be in operation by the states and the federal government. So you're opposed to Mr. Mills on that, and I think that's the case.

Because if we take the whole welfare program and put that in the hands of the federal government, while the costs will rise quickly, and I don't see how we can equalize the payments, how can you give the district of Columbia the money that say people here are $200 a month while in New York, it might be 250, or down south, might be 150, $1 a month, and it would be so uncertain as to who would get what, and some would get much more than the others that I don't know where it would lead us to. And it strikes me that the program that we now have could be well-improved, as I said, by closing the loopholes and seeing to it that the people deserving of it receive it. We don't have too much time. I want to ask you about the Senate, because you're now the seniorest member of the Senate, the President Pro Tem, the Dean of the Senate, all those titles, tell you.

Well, go ahead. I never dreamed when I came to the Senate in 1937 that I'd be the Dean of the Senate. Today I'm not only the Dean of the Senate, but I'm the oldest man of the Senate. How old are you, if you don't mind my asking? Well, I'll be 81 years old, my next birthday. How do you stay in such a good shape? Well, I take care of myself. I have a very rigid schedule that I follow. I keep busy, I don't smoke, and I don't drink, not that I'm against it. But I made a contract and I own a son back in 37. If he didn't start smoking, drinking, I'd quit, so I did. And I have a very rigid schedule, daily at the baths, we have a little gym there. And every day I spend about an hour and a half in the gym, exercising, and taking care of myself, and then, although I have a reputation being a good cook, I don't eat too much

of my own cooking, because much of it is happening. And one thing I've learned is to push the plate away when you've got enough, and I try to keep my weight down, and I think all of that together means a better health. How have you, you have to run for re-election in 1972 again, and I gather you want to run again after that? How have you seen the politics in the South changed since you first ran for election? Well, for one thing, I'm more people, and I'm more problems confronting us than when I first ran. When I first ran for the Senate in 37, the problem was a few. We did indeed with education very much. We had no welfare programs. We had no labor problems of any kind. But today, Congress has its fingers in practically every part of our economy. We take on labor, we take on the schoolteachers now, we take on every segment of our society.

And the work that's been crowded on us, because of that, has increased tremendously. And of course, it makes it rather difficult when we run for re-election. You ask me about running, I hoped to run, I will run in 1972. And my only drawback, of course, would be my age. That is, when people talk of a man 82 years old, they think he's only crutches, or that he's unable to get around, and what I want to do is to get around and see the people, and just show them that I'm still able to represent them. You made a speech in the Senate last year in which you said that you thought that the efforts for integration had actually worsened relations between the races in the South. Do you still think that's true? There's no doubt about it, that it has engendered a lot of, I don't know, the races during my time lived with each other.

That is, we loved each other more or less, and we talked each other. Now there's hatred that's been engendered, and it's bad. And I'm very hopeful that we can live that out sometime. And... Would you want to see the pressures reduced then, is that what you're talking about? Yes, well I tell you, on this school integration, the policy has been in my book, in order to lift them up socially rather than education on it. And I'm for education, and what I'd like to see is given, is that the blacks be given opportunity, the same as the whites, to get educated, so that they can enjoy good jobs and work. You said that you thought separate but equal had worked pretty well, is that what you're talking about? Well, it had worked. Yes, it had worked until the Supreme Court said it was out of tune, and it's my belief that if we had continued, the way we were going, there's no doubt in my own mind, but

that the relationship would have improved, and so would education. I want to get back to the Senate for just a minute. As you know, there's a lot of criticism about the seniority system. What do you think about that? Well, I think it's a good thing, not because... Senate objective beauty, so... Not because I... Well, I tell you, a seniority is a good thing, yes. But you believe when I say that the people of Louisiana would not have sent me for six successive terms, unless I was capable of doing the job. But within the Senate, you think that the seniority is the best system for? I think so. Because you get people that are suited for the job, experienced counts, and the only way you can gain experience is by working there and being there for some time as I have. And I dare say that, I don't say this mostfully, I don't believe there's a man in the Senate that knows more about agriculture and forest as I do, and appropriations.

Because I've devoted all my time to those two committees, and having worked with other senators on those two committees, it strikes me that if anybody is to be chosen to leave those committees, that they ought to select the best talent. And the fact that I have been at the head of the... I mean, only this committee is so long, I believe I'm capable of doing the job. And that applies, it tastes all other committees. Wherever you've got good experience, men who work and produce, I think they ought to be given a chance to need. And that's what seniority means in my book. And what do you think makes the most effective senator? Is it the hard work or the... Well, the hard work in keeping in tune with the people, with the times. I don't like to look back, I try to live the present day life. And try to deal with the people as in our, and do for them the best we can, but try to

make it so that there'll be good Americans and willing to work and go back to our old ways of building a good America. Just one more quick one, and then we'll have to stop. Who do you think have been the greatest senators you've seen since you've been there? Well, it'd be hard to say, but during my experience there, we had, Albin Barkley was a good man. We had President Truman, he was a good senator. I'm afraid, go ahead, one more, we're out of time. Well, we had Arthur Vandenberg on the Republican side, who's a good man. We are out of time. You can give me the rest of the list later. Thank you very much for coming and talking. It was too short. Senator Alan J. Eleander, Democrat of Louisiana, and Elizabeth Drew, writer and Washington

and a tour for the Atlantic Monthly. This is PBS, the Public Broadcasting Service.

- Series

- Thirty Minutes With…

- Episode

- Allen Ellender

- Producing Organization

- NPACT

- Contributing Organization

- Library of Congress (Washington, District of Columbia)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip-512-cc0tq5sk5w

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip-512-cc0tq5sk5w).

- Description

- Episode Description

- Elizabeth Drew interviews Allen J. Ellender, Democratic

- Broadcast Date

- 1971-03-16

- Created Date

- 1971-03-16

- Asset type

- Episode

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:29:59.798

- Credits

-

-

Artistic Director: Braaten, Richard

Director: Deutsch, David

Guest: Ellender, Allen J.

Interviewer: Drew, Elizabeth

Lighting Technician: Bottorf, Harry

Producer: Furber, Lincoln

Producing Organization: NPACT

Technical Director: Mayes, Mike

Video Engineer: Beissel, Don

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

Library of Congress

Identifier: cpb-aacip-55515704a1d (Filename)

Format: 2 inch videotape

Duration: 0:30:00

-

Library of Congress

Identifier: cpb-aacip-2d78ba7dfd5 (Filename)

Format: 2 inch videotape

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “Thirty Minutes With…; Allen Ellender,” 1971-03-16, Library of Congress, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed December 13, 2025, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-512-cc0tq5sk5w.

- MLA: “Thirty Minutes With…; Allen Ellender.” 1971-03-16. Library of Congress, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. December 13, 2025. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-512-cc0tq5sk5w>.

- APA: Thirty Minutes With…; Allen Ellender. Boston, MA: Library of Congress, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-512-cc0tq5sk5w