The Criminal Man; 10; IQ and Crime

- Transcript

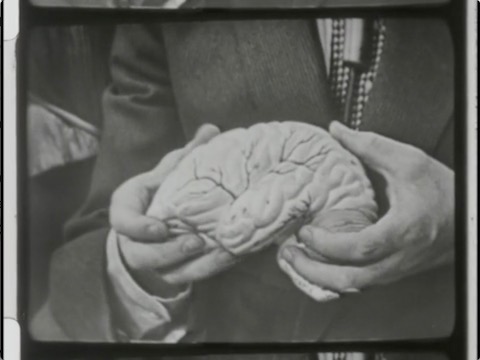

Is the schizophrenic a criminal or mental illness and mental deficiency related to criminality? Here are answers to these and similar questions. A criminal man, a series of television studies of how and why people commit crimes and what to do about it. Your guide for these studies of the criminal man is Dr. Douglas M. Kelly, professor of criminology at the University of California. In this tenth session of our series, Dr. Kelly will begin a study of the relationship of mentality and mental disorder to criminal behavior. He calls this first study IQ and crime. This is a model of a human brain, the organ in which memory, well, other important mental

functions are determined. Actually, it's the seat of consciousness when it fails to operate properly. All kinds of problems can happen. In this day and age, when we're so concerned with the problem of the brain and its function, great many people are interested in the relationship of malfunction of the brain to criminality. Over and over again, when we talk about some notorious criminal, we will hear somebody say, oh, he must be nuts. He's as crazy as a bedbug. Well, actually, at a date, we've never yet been able to find out just how crazy a bedbug is, but we do know a considerable amount about the relationship of the problems of mental illness to criminality.

It is a very simple problem, of course. If we simply say he's nuts and lump it all in one lump, it's pretty easy. But actually, we have two important points of view. There's the problem of the law, which takes insanity, not a medical, but a legal term, which has to do with knowledge of right and wrong and capacity to know the nature and quality of your act. And then, of course, there's the whole field of mental disorder, which can't be summarized very easily and simply saying he must be crazy. If we take, for example, the diagnostic manual of the American Psychiatric Association, we find that we can cover several hundred pages on just basic classifications. I don't plan to be so complicated with this problem in these discussions. And I think for our purposes in the problem of criminology, we can categorize mental illness into a few simple groups.

First of course, we have the defective, and then we have the damaged brains. A person with a defective brain is an individual who fundamentally has had an abnormal or subnormal brain since birth. A person with a damaged brain has a normal brain until either through accident or illness, something destroys the brain tissue. Then there are the functional illnesses. And these basically are the schizofrinics and the manic depresses. These are long technical terms, which we'll discuss out of another section. And of course, in the functional group, there are the anxieties.

And finally, the character defects, or the individuals who basically don't have anything really wrong with their brain and are not functionally mentally ill, but still don't seem to get along very well. For purposes of our present discussion, we'll limit it to the problem of the persons who have defective or damaged brains. When we talk about the problem of the congenital mental defect, of course, the first important question is, why are people not as bright as other people? And here, a great many individuals immediately suggest heredity. As a matter of medical fact, heredity only counts for a relatively small percent of the mental defectives that we have, although over and over again, in office practice, if you have a defective

child, the mother will come in and say, well, I wonder what's the matter with dad's family and the father will come in a little while later and say, well, if I know that this ran in my wife's family tree, basically, I think we should realize that most mental deficiency is a result of failure of the part of the brain to develop normally. During the uterine developmental period, or it may be caused by injury at birth, there are all kinds of things as well as mental deficiency, as hereditary mental deficiency. The next question, of course, that we're concerned with is, how do you tell a mental defect? And this isn't too hard. Mental deficiency, intellectual defect, can be tested fairly simply. For example, in World War II, we were concerned with the problem of men on beach heads. Obviously, an individual on a beach head can't be a mental defect. You want to weather the run or bury his head in the sand.

So we set up a fairly simple set of tests. When we asked people in England, first of all, where are you? We felt this wasn't too complex a question. Be surprised how many people currently go through life, get along, but don't know where they are. The next question we'd ask is, what ocean did you cross to get here? We figured if you'd spent four to six weeks in a convoy at some point, should have looked over the edge and said, what's all that water going by? You could name two oceans, the Atlantic as well, the Pacific as well as the Atlantic, of course, you were in. The next question we thought was, strategically, this was, who are we fighting? Be surprised. We found 67 people in one division who thought they were fighting the British. Then we asked them the name five cities. This doesn't sound complex, but this again is another good nine-year-level question. Now, these are informational questions that found in most standard tests. The type of approach is the type where you do something, the manipulative type.

As opposed to the informational, the type where you have to do some kind of a task. For example, his man fitting blocks of different shapes into a form board. He's doing it quite rapidly, which shows he's reasonably intelligent. Although, basically, this is really about a three or four-year-level test and isn't very hard, but you can make it much harder, as, for example, in the Wexper Bellevue, a standard test. They use a sort of form board, which is really a part of a human face, and then fit pieces into it in order to make up the total structure of the face. They also use a lot of other forms, and then, of course, a lot of informational questions too. In the famous Stanford revision of the termed test, the Stanford revision of the Benin, we also use a large number of various devices, and this gives you a two-part test, which

is probably the better way to do it, part questions and part actual manipulation. Of course, you can just use special devices. For example, here is a technique of a picture set-up. In this particular device, there are a number of little characters doing things, and you pick out free from this particular shelf, whichever block you want, like you put the log here, and that would be good sense. But if, for example, where the boy's kicking, you put the pumpkin, that wouldn't be considered too bright. As a matter of fact, there are literally thousands of these kinds of tests available, and in this cabinet, we have many hundreds. The typical one is the one the British use. This is a matrix kind of a test, and it consists of a matrix from which a piece has been cut, and this piece, of course, fits, or in the next one here is the cut and this piece

fits. It does look very hard, but when you get to some of the other tests, you'll find it's pretty complex. With these various techniques, then, we can readily determine your mental level, and we find that about 1 out of every 5, roughly 20% of the population are to some degree below normal. This doesn't mean they're all marked defects, but it does mean they have some difficulty just in their intellectual function. Our next problem is the relationship of mental deficiency to criminality. Does mental deficiency cause crime? It used to be considered a major cause. A great many authorities had tested people in prisons and found them to be under par mentally, and reasoned that this must be the basic reason why they were criminals. Modern investigation has proved this not to be true. That's saying, Quentin, for example, the overall IQ average of the prisoners is about

100, and the IQ average of the American public is also 100, so we find that criminals are people and they're just about as smart. As a matter of serious fact, I think we ought to consider the idea that a great many people who commit crimes aren't apprehended, and the smarter you are, the less apt you ought to get caught. So if the population of Quentin is normal, then there's an extraordinarily good chance that the criminal on the whole, including those who haven't been caught, may well be a little smarter than the average. From this, I think we can say quite definitely that there is no specific relationship between mental deficiency and crime. Our last problem is what kind of crimes do mental defects if they commit crimes commit. And here we find what you would expect simple, repetitious patterns like routine burglaries, occasional car thefts, car clouding, opportunistic crimes, this sort of thing.

Again, a mental defective is a little more unstable. He doesn't have as good control frequently as does the norm, so he's more apt to explode. We find explosive crimes like rape or homicide included in the mental defective group. And last, mental defectives frequently behave like little children, so along with the petty theft, opportunistic crime and impulsive explosion, we find arson as a fairly common kind of crime committed by the mental defect. These three great groups, then burglaries and simple thefts, explosive assaults, occasional rapes and arson, make up the general pattern of the mental defect. One other belief, I think, we ought to get rid of, and this is the notion the mental defect is a gangster. You see pictures, for example, in motion pictures and on television of a big husky guy with his mouth open, he's the dope, he's the hooking lug who commits the criminal act.

This isn't true except in the pictures. The average gangster doesn't want a mental defect, and the first place in his gang, and secondly, defects don't go around with their mouths open, because around breathing through his mouth it's because he has ad noise, not because he's a mental defective. The next group of people in whom are interested are the people who have been normal in their development, but then developed some kind of damage to their brain. Now the causes of brain damage, of course, are sometimes obvious, sometimes not so clear. If we take this rubber model, it's easy to see that a blow on the head, crushing the skull, could well easily damage the brain, and then we have post-traumatic damage, brain damage from an injury. A second common cause of brain damage is the problem of infectious disease, and cephalitis or other illnesses attacking the brain, or systemic illnesses with high fever, may yield residual

damage to the brain tissue itself. Then again you can get various toxic damage from poisons like chronic alcoholism, for example. And finally there are certain specific diseases of the brain itself. You may have cancers or tumors, or you may have a disturbance in the vascular supply. The blood vessels supplying the brain itself may plug up, or incirculatory diseases, diseases of the heart, or the other vessels may cause starvation of the brain through lack of blood with secondary damage and loss of the tissue. Finally, in the brain itself we may get damaged from simple senile or apparently spontaneous deterioration. Why the damage occurs is not quite clear yet to medicine, but there's no doubt of certain people simply wear out in their brains before they wear out elsewhere, even as do other

precise types of machinery. And so these general causes, damage from injury, infection, toxicity, blood vessel changes and spontaneous damage, can give you various permanent tissue changes. In the diagnosis of these tissue changes, ordinarily we used to do a physical examination. A routine neurological study, including for example the use of percussion hammers to elicit reflexes, the use of a dynamometer to elicit various muscle changes, the use of various kinds of devices to determine sensitivity to pain, heat, pressure, and the use of various kinds of vibratory instruments to determine various kinds of vibratory changes are important in the evaluation of damage in the brain primarily in those areas back of the frontal lobe. The part of the brain we're interested in, of course, is the front part, the so-called

frontal lobe, and this used to be called the silent area because this part of the brain is not shown to be damaged on a routine neurological study. Recently, however, in the past 20 or 30 years, we've discovered that certain psychological tests are of extraordinary value in determining this sort of thing. And here is a young lady taking one of these tests, sorting out, apparently, some little blocks. She shorts these sorts out these various blocks by shape, and then she could sort them out by color, showing she grasps their relationship. Another way of doing this would be to use a more complex test, blocks which are not only of different shape and color, but also different in height. This requires considerable abstract capacity, a capacity lost when the brain is damaged. Another equivalently similar test is to take four little colored blocks and then ask

the patient to match the various types of models. And as she attempts to match these, we have a pretty fair measurement over capacity to reason and think abstractly, capacities which disappear when the brain is damaged. Another very useful test, although it looks somewhat odd, is a sorting test in which you apparently have a pile of miscellaneous junk, or actually those selected very carefully psychologically. If, for example, we put this item down, a toy spoon and a toy hammer and a ball, ask her to find out what goes with this. She selects quite rightly a toy dog and a toy bell and a toy fork, all toys showing that her abstracted pattern is working with toys. She might have selected other items, but this is a good, normal pattern of behavior.

These kinds of tests are particularly valuable in the determination of brain damage. Another test, which is extraordinarily useful, is the rush off test. And here we use a set of ten standard ink blocks. For example, one is just a black plot, another is black and red, and others are multicolored, and here we're concerned with how does the individual handle the material. We actually asked him to tell us what it might be, but fundamentally, we really don't care what he sees it to be, we're primarily interested in what visit appear like to him in his handling of a new situation. This way, we get a little sample of his behavior or sample of how he handles it, and if we know our statistical data and can compare his behavior with other brain damage persons, in no time at all, we can make a diagnosis of brain damage.

Of course, once we've determined the presence of brain damage, the next question is, what's the relationship of brain damage to criminality? You must remember that a brain damage person is an individual who has matured normally, and now suddenly has his control areas cut away. As we pointed out a second ago, the funnel part of the brain is the part with which we're concerned, and an individual with brain damage, he loses the use of this part of his brain. In the funnel part of the brain are the centers for memory. This is why persons with brain damage have marked recent memory loss, and the centers for what we would call psychologically civilization, the capacity to get along, the capacity for interpersonal relationships. When these are knocked out by damage, then the individual becomes deteriorated. He isn't as clean as he used to be.

He isn't concerned with other people. He may swear more frequently. He's more easily irritable, and the third factor is an explosive emotional pattern. He loses the controls, which are inherent in this front part of his brain. If we now apply these findings to a normal person, say a person who is deteriorating, we find his personality shifts. He becomes more quarrelous. He becomes more explosive. He is apt to get into fights, and these are the kind of things that brain damage actually produce in terms of criminality. If we look at the range of possible crimes, he doesn't commit burglaries or robberies, but he's more apt to blow up in an interpersonal way. He may be guilty of disturbing the peace, one of the classic cases I recall is the crowbar case, or an individual had a crowbar driven through his head. When he recovered, a buddy saved the crowbar, and then much like the ancient mariner went

from person to person in the village, with the crowbar in one hand, grabbing them by the shirt front with the other, and demanding that they hear his story. Since he waived the crowbar almost everybody reasonably listened, and this kind of a problem became a police problem on the basis of disturbing the peace. I think it was good that he was arrested because at some point he might have batted somebody else on the head with the crowbar, and you know the thing might have gone on and on indefinitely. Another kind of crime that you get with brain damage persons are ideas of suspicion. Persons who are getting old and senile frequently recognize this, and they become very suspicious and worried about other people. They feel, for example, that their relatives are attempting to take over their estate, or that their families are unfaithful. And then, because of the combination of the suspicions, plus the marked impulsivity

brought about by the damage, they then will suddenly erupt in a homicidal, violent attack up on whomever they suspect. When you read in a newspaper, then a series of headlines that an oldster has suddenly killed his wife or are gone to somebody in neighbor's house and shot the neighbor and his wife and his children, the chances in these kind of crimes are they probably are due to damage. There's one other problem of organic change that's important, and this is the problem of epilepsy. Epilepsy is a disease which has been well known to mankind since its earliest history, actually, and because of its spectacular quality, the sudden convulsion, it's always been held in a little awe. Oddly enough, Lambroso believed that epilepsy was a major cause of crime, and actually ascribed at one time, all criminal behavior to the fact that the criminal was an epileptic

or a potential epileptic. Nowadays we know there are dozens of things, maybe 50 or 60, different kinds of condition that produce convulsions. If the convulsion is produced by actual changes in the brain, it's best diagnosed by an electroencephalogram, a device which picks up electric currents from electrodes glued onto the head and records the current after amplification on a graph. If we take a look at some of these graphs, we can see that the rhythms are pretty definite. Here is a normal picture, they're different depending, of course, on the part of the brain they're taken from, but in the whole, they're pretty routinely regular. If we look at an epileptic graph on the other hand, we find that they are markedly different from the normal, and with this technique, epilepsy can be easily identified. This is an important thing criminologically, because a great many defensive attorneys

have come up recently with the idea that if a person has some kind of brain damage, this makes him not responsible. And of course, if they do an electroencephalogram and he has abnormal waves, this to their way of thinking proves it. It turns out that a fair percent, six or seven percent of normal people have disturbed brainwaves without being disturbed clinically. So this isn't a good defense. An epileptic crime is probably contrary to lombrosos thinking quite rare. Epileptics make them at crimes, but their crimes will be non-motivating, quick, explosive assaults, and when they occur are obvious and I might add, in my experience, extraordinarily infrequent. In our discussion this today, then we've noted that we have covered pretty well one area of the problem of mental illness in relation to crime.

Again, let me stress a factor that I feel most important, that much of the popular thinking is probably based on false concepts and misinformation. The individual who is mentally defective, who is subnormal, an individual of the moron or lower level, will not tend to be more criminal, but rather will tend to be less criminal. A person with brain damage, a person who has organic damage, probably is less apt to commit crimes than a normal person, and that either of these groups do commit crimes, they're relatively easy to diagnose and the criminal pattern reasonably simple to predict. Epileptics statistically, in contra-distinction to popular belief, actually commit fewer crimes than do normals. This we can say quite specifically because remember epileptics are individuals who are

reported, and being a reportable disease, we know pretty well how many there are. We find that the epileptics commit crimes at a ratio of seven-tenths of a percent to the normal ratio of individuals who are not epileptic. From this I think we can derive the conclusion that individuals with damage of one kind or another, do have a relationship to criminal patterns. But the relationship is quite specific, easy to diagnose, and much less than the average person believes. Sometimes it's spectacular. For example, Robert Lai, the top politician in Germany, their head labor leader, had marked brain damage, damage during which time he acted as their chief politician. I of course wouldn't want to derive any conclusion between the relationship of brain damage and political success, but Lai did explain the job because of his impulsivity and his

lack of need to adhere to the truth. In our next series, we'll consider the problem of some of the other kinds of mental illness, for example, the functional ones, the schizophrenia, the manic depressive, and the anxious persons. And on another section, we'll take up the question of the character defects, individuals who seem to have matured perfectly normally from an intellectual viewpoint, persons who have not been brain damaged and who do not suffer from any kind of mental illness. And yet these people are constantly in trouble and are one of our major problems in terms of repetitive crime. As we review the problem of mental illness then in relation to crime, we find some specific relationship with defectives and damaged, but no major degree. And so we will next turn to the other groups in our constant search for the arch-triminal

of our country, the criminal man. The series of television studies of the nature and patterns of criminal behavior. Your guide for these studies is Dr. Douglas M. Kelly, physician, psychiatrist, police consultant, professor of criminology at the University of California. This is National Educational Television.

- Series

- The Criminal Man

- Episode Number

- 10

- Episode

- IQ and Crime

- Producing Organization

- KQED-TV (Television station : San Francisco, Calif.)

- Contributing Organization

- Library of Congress (Washington, District of Columbia)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip-512-9p2w37mp1m

- NOLA Code

- CMLM

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip-512-9p2w37mp1m).

- Description

- Episode Description

- Virtually all criminal behavior has its roots deep in psychological disorder. This program is the first of several devoted to the psychic problems and their relationship to criminality. Dr. Kelley deals with the mentally deficient individual, the person with the low IQ. He explains congenital and developmental mental problems and organic brain damage and deterioration. (Description adapted from documents in the NET Microfiche)

- Series Description

- The Criminal Man is a definitive study of the cause, prevention and treatment of crime by the late Dr. Douglas M. Kelley, police consultant, psychiatrist and professor of criminology at the University of California. The series, which takes its title from Lombrosos original work in the last century, incorporates a great number of dramatic re-enactments using highly skilled actors and films as illustrations. Dr. Kelley uses the first six episodes to define crime and criminals and to destroy the myth, folklore and common superstitions which have long surrounded crime. The second group of episodes analyzes the true causes of crime and posts guides to the prevention of these causes. The two final episodes look at current penal policies and their weaknesses regarding rehabilitation. Dr. Kelley indicates the lines of penological progress which he thinks would provide the greatest benefit to society. The 20 half-hour episodes that comprise this series were originally recorded on videotape. Dr. Douglas M. Kelley, police consultant, psychiatrist and professor of criminology at the University of California, gained national reputation as a brilliant theoretical and practical criminologist at the time of his work as consulting psychiatrist at the Nuremberg Trials. The public also remembers his testimony in the Stephanie Bryant kidnap-murder case. Dr. Kelley was a Rockefeller Fellow at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, and at that time (1940-41), he compiled clinical contributions for Dr. Bruno Klopfers book, The Rorschach Technique. His studies at the University of California led to his receiving and AB in 1933, his MD in 1937 and to his residency in psychiatry from 1937 to 1938. he studied also at Columbia University. He was married in 1940 and was the father of three children. During World War II he was a lieutenant colonel. (Description adapted from documents in the NET Microfiche)

- Broadcast Date

- 1958

- Asset type

- Episode

- Rights

- Published Work: This work was offered for sale and/or rent in 1960.

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:29:25.625

- Credits

-

-

Host: Kelley, Douglas M.

Producing Organization: KQED-TV (Television station : San Francisco, Calif.)

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

Library of Congress

Identifier: cpb-aacip-a2e6724b9d1 (Filename)

Format: 16mm film

Generation: Copy: Access

Color: B&W

-

Indiana University Libraries Moving Image Archive

Identifier: cpb-aacip-d7e549bd75a (Filename)

Format: 16mm film

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “The Criminal Man; 10; IQ and Crime,” 1958, Library of Congress, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed December 24, 2025, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-512-9p2w37mp1m.

- MLA: “The Criminal Man; 10; IQ and Crime.” 1958. Library of Congress, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. December 24, 2025. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-512-9p2w37mp1m>.

- APA: The Criminal Man; 10; IQ and Crime. Boston, MA: Library of Congress, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-512-9p2w37mp1m