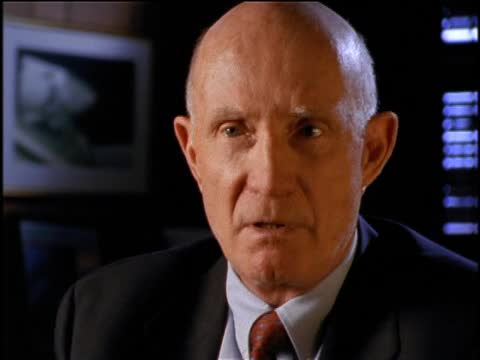

NOVA; To the Moon; Interview with Thomas P. Stafford, NASA astronaut, Air Force Officer, and Commander of Apollo 10, part 2 of 3

- Series

- NOVA

- Episode

- To the Moon

- Producing Organization

- WGBH Educational Foundation

- Contributing Organization

- WGBH (Boston, Massachusetts)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip-15-kk9474835k

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip-15-kk9474835k).

- Description

- Program Description

- This remarkably crafted program covers the full range of participants in the Apollo project, from the scientists and engineers who promoted bold ideas about the nature of the Moon and how to get there, to the young geologists who chose the landing sites and helped train the crews, to the astronauts who actually went - not once or twice, but six times, each to a more demanding and interesting location on the Moon's surface. "To The Moon" includes unprecedented footage, rare interviews, and presents a magnificent overview of the history of man and the Moon. To the Moon aired as NOVA episode 2610 in 1999.

- Raw Footage Description

- Thomas P. Stafford, NASA astronaut, Air Force Officer, and Commander of Apollo 10, is interviewed about his experiences in space during the Gemini and Apollo programs. Stafford describes flying with Wally Schirra during the Gemini 6 mission, and explains the issues that he and Gene Cernan experienced with their space suits during Gemini 9. Right before they left for the mission on Gemini 9, Stafford was told to bring Cernan's body back if he died during his spacewalk, which would have posed many issues, and he only told Cernan about it after they had both safely returned to Earth. During the Apollo 10 mission, Stafford describes the difficulty of judging distances while flying above the moon because of the lack of landmarks, and explains their discovery of mascons on the moon.

- Created Date

- 1998

- Asset type

- Raw Footage

- Genres

- Interview

- Topics

- History

- Technology

- Science

- Subjects

- American History; Gemini; apollo; moon; Space; astronaut

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:23:20

- Credits

-

-

Interviewee: Stafford, Thomas P., 1930-

Interviewee: Stafford, Thomas P., 1930-

Producing Organization: WGBH Educational Foundation

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

WGBH

Identifier: cpb-aacip-490bb1fce1d (Filename)

Format: Digital Betacam

Generation: Original

Duration: 0:23:21

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “NOVA; To the Moon; Interview with Thomas P. Stafford, NASA astronaut, Air Force Officer, and Commander of Apollo 10, part 2 of 3 ,” 1998, WGBH, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed February 19, 2026, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15-kk9474835k.

- MLA: “NOVA; To the Moon; Interview with Thomas P. Stafford, NASA astronaut, Air Force Officer, and Commander of Apollo 10, part 2 of 3 .” 1998. WGBH, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. February 19, 2026. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15-kk9474835k>.

- APA: NOVA; To the Moon; Interview with Thomas P. Stafford, NASA astronaut, Air Force Officer, and Commander of Apollo 10, part 2 of 3 . Boston, MA: WGBH, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15-kk9474835k