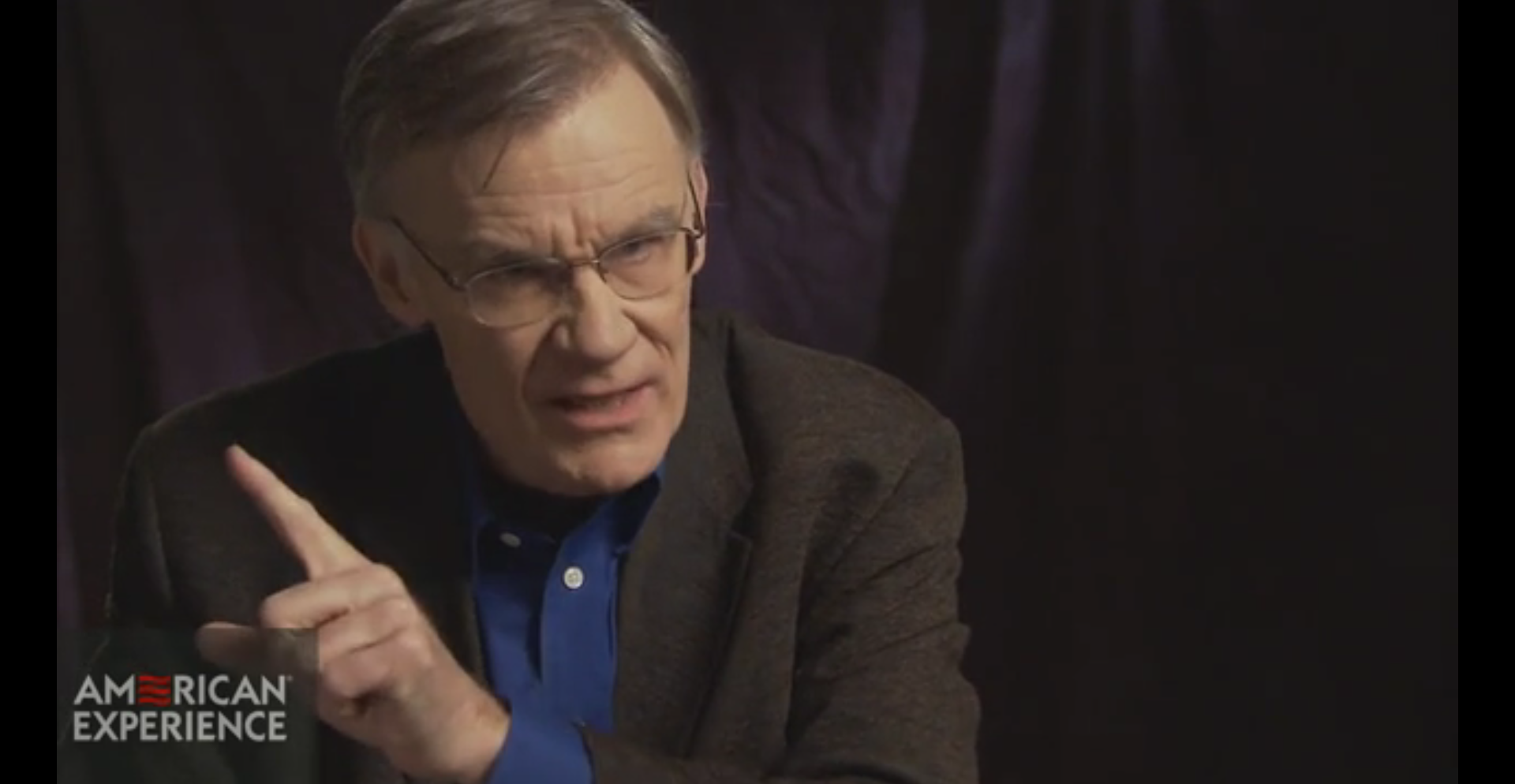

American Experience; The Abolitionists; Interview with David William Blight, part 2 of 6

- Series

- American Experience

- Episode

- The Abolitionists

- Raw Footage

- Interview with David William Blight, part 2 of 6

- Contributing Organization

- WGBH (Boston, Massachusetts)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip-15-cc0tq5s99x

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip-15-cc0tq5s99x).

- Description

- Description

- David William Blight is Class of 1954 Professor of American History at Yale University and Director of the Gilder-Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance and Abolition. His works include: Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory; Beyond the Battlefield: Race, Memory & the American Civil War; and A Slave No More: Two Men Who Escaped to Freedom, Including Their Own Narratives of Emancipation.

- Topics

- Biography

- History

- Race and Ethnicity

- Subjects

- American history, African Americans, civil rights, racism, abolition

- Rights

- (c) 2013-2017 WGBH Educational Foundation

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:25:51

- Credits

-

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

WGBH

Identifier: cpb-aacip-1ab6a219f5d (Filename)

Duration: 0:25:52

-

Identifier: cpb-aacip-a2aa44a7556 (unknown)

Format: video/mp4

Generation: Proxy

Duration: 00:25:51

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “American Experience; The Abolitionists; Interview with David William Blight, part 2 of 6,” WGBH, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed February 27, 2026, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15-cc0tq5s99x.

- MLA: “American Experience; The Abolitionists; Interview with David William Blight, part 2 of 6.” WGBH, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. February 27, 2026. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15-cc0tq5s99x>.

- APA: American Experience; The Abolitionists; Interview with David William Blight, part 2 of 6. Boston, MA: WGBH, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15-cc0tq5s99x