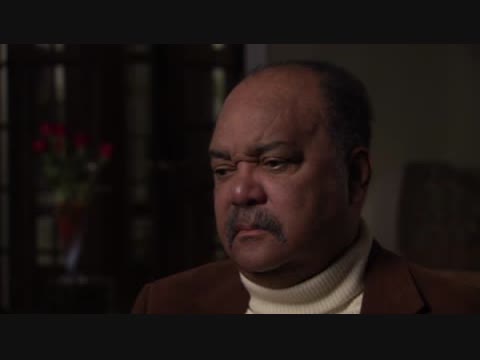

American Experience; Freedom Riders; Interview with Dion Diamond, 2 of 2

- Transcript

[Diamond] Prior to arriving in Jackson, Mississippi we all were aware of what the penal system and what the cops, if you will, were about. We were indeed afraid, we were aware of what they could do, but again because of the press we felt somewhat safe. The penal system-- everybody knows Parchman and Angola in Louisiana, I mean those were the drop dead places wherein you could disappear. So yes there was a fear, but again you know, we never thought in terms of the FBI and how they could protect us, we merely thought that the FBI would

protect us but the issue became the FBI agents lived in the very communities that we were trying to desegregate. So, while we thought we were being protected by the FBI, we also found out later. [Interviewer] Okay, let me ask you again about-- seemed to me that in some ways there's a different fear than the penal system. [Diamond] That too, [cough] That too is true. We were entering this black hole but nevertheless our naïveté was such that we thought we were being watched over, not just watched. But we thought were being protected by the federal system. I mean we knew we were in the public limelight, so therefore if anything was going to happen to us, the FBI

would protect us and even as we went into this dark, black hole, somebody would know. We were being-- we had an overlord, we had a watchful eye, it wasn't as if I were Emmett Till, you know, one black guy taking on the establishment, it was a matter of we collectively were taking on the establishment and everybody was watching. So I mean if anything happened, the whole world was watching. [Interviewer] So you thought that-- you all thought that you were protected by the FBI, how stupid is that? [laughs] [Diamond] Only after the fact. [laughs] Only after the fact if I discovered that-- thinking that the protection that I thought we had really was tenuous.

[Interviewer]: I want you to-- I don't think you ever ended-- what was the reputation of the Mississippi penal system? [Diamond] Oh, somehow Mississippi and Louisiana just had a reputation of being the ugliest, the most darkened penal systems in the country. I keep relating to Louisiana because I had been a guest of of their penal system, but Mississippi had the reputation of being a chain-gang, and "hey, you're black, you can get slapped around and you can disappear." But again, we thought that we were protected because the eyes of the world-- after that

burning of the bus and how it spread all over the various newspapers and tv of the world, somehow we thought that that was protection. Again, 50 years later that was nothing more than naïveté, they wouldn't do it on camera, but believe me and I can attest to a cattle prod, I mean when no camera was around they could make life very difficult for you. [Interviewer]: Okay, let's cut. Were you-- so, um, you know, so you're going there, you're going into the Mississippi penal system, so were you like willing to give your life for the cause?

[Diamond]: Quite frankly I never thought in terms of giving my life, I mean you have to recall, I was 19 years of age, soon to be 20, but nevertheless because, again this was an escapade. I'm trying to minimize, if you will, how I thought this one through. I mean it wasn't as if I had such braggadocio, you know, and I just saying "I'm taking this cause," it was like this is something I believe in but I don't think I'm going to die from trying to assume this

belief. [Interviewer]: Okay, um, talk to me about your cellmate at Parchman. [Diamond]: I don't know how it came about, um, but Jim Farmer, the national director of CORE, whom, honestly, I did not know him from Adam, a perchance hookup between two people because he wasn't even on, to my knowledge, I don't think he was on the same bus that I was on but nevertheless I did not know that man, I did not know his history, I did not know that he was someone I should -- and do, and did --

revere. There've been two people in life, Jim Farmer being one of them, as you might guess, I'm a relatively talkative person. Jim Farmer was a person who was introspective and non-talkative. When you're in a six-by-nine foot cell with one other person for 24 hours a day, for me I have to have a conversation. Jim was a person not only philosophical, but he was also somewhat monosyllabolic [sic]. If you asked him a question to try to start a conversation, he would either say "yes," "no," or find five words to intersperse.

But that's the type of person that can make an impression upon you just by his quietude. [Interviewer]: Um, okay, I'm gonna ask you that again, if you can talk to me, uh, I think that one of the things you talked to Lorenzo about, was the fact that you thought that [cough] at this point he was realizing the weight of all these people [Diamond]: yes [Interviewer]: that were in jail, and if you can start out by saying, "they put me in a jail in a cell with Jim Farmer," you kind of never said that. You know and that's the kind of thing that would help, you know, do you know what I mean? You got to say the cell with Jim Farmer and he was quiet, although you always hear about him being such a talker and a speaker but I think one of the notes that I was so intrigued by was your statement that maybe at this point he was feeling the weight of these Freedom Rides that he had started.

And that now there's lots of people going to jail. Okay, so talk to me about the fact of how they put you in this cell. [Diamond] Upon being arrested in Jackson, with more Freedom Riders arriving on a daily basis, the city jail, the Hinds County jail, overfilled. They sent us to Parchman Penitentiary. With more people coming in every day they needed more space. Somehow by the luck of the draw, I got tossed into a six-by-nine cell with Jim Farmer, the national director of the Congress of Racial Equality, who indeed started this series of sit-ins and the Freedom Ride. [coughs]

Jim lamented in that cell, "how we're going to pay the bail for all of these kids who are getting arrested?" I think I witnessed-- I think I witnessed the weight of what he had started. I don't want to use the word "torment," but it became obvious that he knew that it was CORE who had started this Freedom Ride. I'm not talking about the Freedom Ride of 1947 but nevertheless being in that cell with him, I could see him pacing in a six-by-nine cell

and I didn't realize it at the time but I think the weight was obviously there. [cough] [Interviewer] Okay, I want you to tell me again, sorry to ask you this another time, but talk about being in the jail cell with Farmer, who had started the Freedom Ride. [Diamond] Again I wasn't-- when the Hinds County jail overflowed with incoming Freedom Riders they needed to find additional space. They sent us to Parchman, the state penitentiary, and I have no idea how they assigned who would be bunk-mates, if you will, or cell mates, but somehow I got linked and shared a cell with Jim Farmer,

the national director of CORE, who was indeed responsible for this Freedom Ride. I had no knowledge whatsoever who Jim Farmer was, I mean I was in a cell with a person of great-- I don't even know how to put it, I mean the man had an aura about him and I didn't realize that "Hey, so what, it's Jim Farmer." I'm in the cell with the guy and I didn't realize at the time that that meant that he had the weight of all of the people who were getting arrested on his shoulders because they couldn't find the money to post the bail for everybody who was getting arrested.

So I guess, and we never discussed it, I guess he just said "well, all these people here at Parchman, as well as all the other people who we left behind in the Hinds County jail, a direct result of what I, Jim Farmer said let's do." Again I didn't realize it at the time and it only comes with age, wisdom, and circumspect, but Jim obviously had to be thinking "I'm responsible for all of this." And I at age 19 was not aware of what that kind of responsibility can

take in terms of its toll on a person. Jim obviously was at least 25 to 30 years my senior. At that particular time I'm just lacksadaisical [sic], I'm nonchalant. [Interviewer] Okay, let's cut. [PA] This is room tone. [silence] [Interviewer] (Tensions between ) SNCC and CORE and SCLC. [Diamond] I cannot describe

tension between CORE and SNCC. I think we... Again, SNCC was no more than a loose affiliation. It was not an organized institution. The tensions that existed between CORE and SNCC were minimal mainly because of the fact that each of the students came from their individual hometowns or school towns, if you will, but there was indeed tension between SCLC and SNCC. SCLC, it was monetary. SCLC raised money through churches and they tried to claim, if you will, credit for all of the

student activities, i.e. everything the SNCC was doing, SCLC was trying to claim credit for. And we knew that "Hey, they haven't put a dime in this coffer, and this is our own individual activity," but nevertheless, when Dr. King and SCLC staff had rallies in various churches in the South, they would claim credit for what the kids, i.e. SNCC was doing. And we disliked that intensely because we were not the offspring or the child of SCLC, but SCLC was trying to claim us as their children. [Interviewer] It seems that on the Freedom Rides it was SNCC

that was putting their lives and their bodies on the line. [Diamond] Right. [Interviewer] Say that. [Diamond] Well, if you look at the early phases of the Freedom Ride, they were all kids and students. It was only in the latter stages of the Freedom Ride, I don't know how many total numbers were finally arrested in either Jackson or Mobile or wherever. But it was only late in the game when the ministers-- I think there was a whole busload of clergy-- but if you look at the dates of the arrested persons, you will find that the ages of the persons initially arrested were those students, youngsters. The adults did not join the Freedom Ride until the later stages. [Interviewer] So? [Diamond] Well,

again, when you're in jail you really don't know what's happening in the real world and the outside world. We would only get messages as to what SCLC said it was doing. [Interviewer] I'm just trying to get the point across that you were kind of putting yourselves on the line, but if you don't want to say that that's--

- Series

- American Experience

- Episode

- Freedom Riders

- Raw Footage

- Interview with Dion Diamond, 2 of 2

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip-15-5h7br8nc20

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip-15-5h7br8nc20).

- Description

- Description

- Dion Diamond was a student from Howard University on the Montgomery, Alabama to Jackson, Mississippi (Greyhound) ride, May 24, 1961.

- Topics

- History

- Race and Ethnicity

- Subjects

- American history, African Americans, civil rights, racism, segregation, activism, students

- Rights

- (c) 2011-2017 WGBH Educational Foundation

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:19:32

- Credits

-

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

Identifier: cpb-aacip-36bc84decff (unknown)

Format: video/mp4

Generation: Proxy

Duration: 00:19:32

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “American Experience; Freedom Riders; Interview with Dion Diamond, 2 of 2,” American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed February 21, 2026, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15-5h7br8nc20.

- MLA: “American Experience; Freedom Riders; Interview with Dion Diamond, 2 of 2.” American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. February 21, 2026. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15-5h7br8nc20>.

- APA: American Experience; Freedom Riders; Interview with Dion Diamond, 2 of 2. Boston, MA: American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15-5h7br8nc20