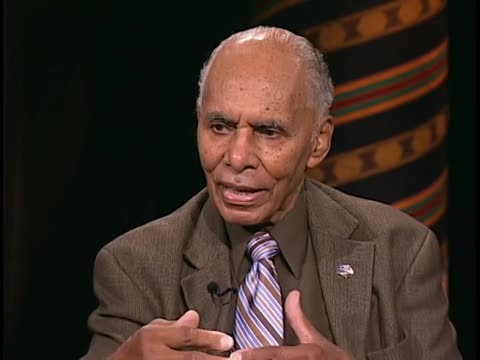

African American Legends; William C. Rhoden, Sports Journalist, New York Times

- Transcript

The African-American legend series highlights the accomplishments of blacks in areas as various politics, sports, aviation, business, education, and literature. We will explore how African-Americans have succeeded in areas where they have been previously excluded because of segregation, racism, and lack of opportunity. I'm your host, Dr. Roscoe C. Brown, Jr., and with us today is Bill Roden, sports journalist from the New York Times and author of the new book, $40 million slaves. Now, what does $40 million slaves say? What's the new reaction to it? Well, we'll see. I like the title, by the way. The title is very stunning. But it just, the title comes from a comment that Larry Johnson used to play for the next you know, in 1999 when they had the championship. He had Boycott as a Media, you know.

And so he was fine, you know, starting with fine. You got to talk. You got to talk. He didn't talk. So finally, he said, okay, you want me to talk. I'll talk. So he had also, and he continued to blast the media, you know, just blast them for being, everything for being bigoted. Then he said, you know what, the only people I care about on my teammates down there in the court. So on this team, we're a bunch of rebellious slaves. So the next day, of course, he was like, out of all stuff he said, they just killed them about that. Well, so the next season, the next were playing a game against the Clippers of Los Angeles. So there's this white fan who had been heckling them all. Okay. So during the time out as a mixed walk to the, you know, bench, this white guy says, Johnson, you're nothing but a $40 million slave. And so Diane Chaney told us, and I thought it was very interesting that A, that this fan remembered what Johnson from a year ago, but B, I thought it was very interesting that Larry Johnson would choose that particular metaphor to try to get these reporters to understand how he saw his relationship

to power. So, you know, we pulled that out. They had to actually Chris Jackson. It's a good way to pull it out. And at a first, I think, wow, that's pretty jarring. But then, you know what, it really cuts right to the heart of what we're talking about. What is your really, I mean, we've grown, you know, the book starts on a plantation with plantation, affluent plantation boxers, runners, rollers, you know. And the question, it's kind of racist, has a relationship between those slave athletes and their owners fundamentally change from then and now between these athletes and their owners. And the answer is kind of, well, in many ways, it really has it. As far as the reaction goes, you know, I was at the Atlanta Falcons training camp in August. And Algae Crumpler and Warwood Dunn walked in. And he said, oh, Mr. Roman, we just got your book. Man, we're reading it. And the guy at the Jacksonville Jaguars bought about 40 copies and had me come down there and talk to somebody

players. So, you know, and I know the reaction for just the community. I mean, people, you know, the reviews have been outstanding for the community people that, wow, you know, this is really, it's historically very interesting. And wow, you know, I think it kind of people like to extent to reading it. I think people are kind of like, it's a lot to digest or maybe just kind of weighty. You know, so I really haven't had any reality, like, man, this is, you know, why did you, I think some people look to the covers and will play, but then I think when they start reading it. So, I'm not calling you slaves. I'm just questioning your relationship to power. And really, I'm saying that you guys have so much power, man. I mean, it's, what you guys could do together. Because, you know, so anyway, it's really, and we can probably talk about it. But it's really, it's suggesting how we as athletes are a metaphor for what we as black people have to do in the 21st century. We got to get back to kind of doing things together.

We're going to put everything in perspective. This is really a 20th century phenomenon. Black athletes didn't really begin to be recognized until the 20th century. And then when Jack Johnson won, the title they took it away from him and so on. And it wasn't until 1936 when Jesse Orange won the Olympics in 34, 35, 38 when Joe Lewis began to be the world champion that people again to say, look, black athletes can really do it as well as whites. Because the question of that time was, could they even do it? But now, clearly they could do it as well as whites. And then Jackie comes in in 47. And in the end of the most prejudices for them all, Major League Baseball, which included blacks. And then by the time the 60s developed the 70s, 25% of the ball players were African-Americans. And the basketball 50%. And you remember at one time in basketball, you couldn't

have more than three black players on the court at one time. And that was in the 50s and early 60s. You had one great star, you know, no role players. Remember, they were on the best. You either played, you either, you either star or you honor, you're one girl, one girl's rise, rise, go about eight years ago, and I just began in the book. She said, you know, it's like the Black History or something. So at the end of it, she said, well, Mr. Rodden, who was the first white player to integrate the NBA? You know, it's like, you know, it's like, it's done. But you know, for a lot of kids who were born after 1970, everything you talked about, I mean, you lived a lot of stuff. It was irrelevant. I mean, the idea that somebody couldn't play basketball was like completely or foreign concept. Well, this has really been turned to the largest society with African-Americans. People like myself and people like you understand how far we have come and how impatient we are

because we haven't gone further. Many of the young African-Americans think that things are always this way, that we always had the opportunity that if you're good, you're going to make it. And of course, that really still isn't true. Well, you know, and you say that, I mean, that's, and I guess I came out of this book and we took me eight years to write it. And I remember talking to Dr. Franklin, John O. Franklin, at the very end. And he said something a little depressing, because, you know, he was like 90 years old, 90 years old, and I went years old. And he said, you know, the more I see with this, the more pessimistic I get. You know, I hope just because, you know, but, and I was thinking the same thing is that I had no idea. I mean, you know, I grew up in the 60s and all that. I knew what racism and that kind of stuff. But, you know, the depth, I guess I had no idea of just how deeply entrenched this racism is just throughout the pores and just the fiber of, I mean, I was just everywhere, you know. And so now, first,

you know, I used to tell somebody, I mean, I would never use all this racism. I'd explain it. Now, you know, it's kind of what it is. I mean, the reason that the press box is it's still predominantly white. And we're getting worse. And I guess that's my point. We made progress, but it's almost like we're on a merry-go-round, where, you know, you kind of go round and round and the horses go up and down and seem so exciting and all that stuff. But when it stops, you get off and you're really the same place you were, you know, you haven't gone anywhere, you know. And I think, yes, and we made progress. We made, in other words, the whole premise of our existence is wrong. Like, but Jackie Robinson, all that, everybody knew that we could play baseball. And by new, I mean, so the premise was wrong to begin with. So we spent all this time trying to prove that we can play baseball. If you look at the Harlem Rens, everybody knew that we could play better than that. The first world champion. Yeah, the first world champion. Yeah, the people. So I guess the idea is, once you go start getting back in history, and I think a lot of

young people, whether it's my book, your book, you know, and you're getting history, it's a waiting minute. You know, the whole premise of this stuff was flawed. So maybe you get some power from knowing that you were always a substantive people. It's the definition has always been wrong. See, the dilemma for African-Americans is, do you get mad, or do you get even? How do you get even? That's why. And then the question is, how do you get even? How do you get even? And with business opportunities, you know, some black debate, lots of money, and in various kinds of businesses, that's in part getting even. But even there, because of racist policies and financial equity and investment and so on, it keeps this multi-billion dollar market of African-Americans controlled by the white business community. So this is the dilemma we faced. I'm not quite with John Hope that I get depressed. I get angry. But I think anger motivates us to find ways of challenging the system.

I don't know if our kids get angry. I would love for our kids. I mean, you talk with anger. I mean, you know, some of the just, it seemed like our threshold of getting angry is like, what is it take? But and that has to do with how do we work together? I come out to a civil rights movement. I was a Tuskegee airman. We were going to break the barriers. We stung together and we wrote together and we flew together and so on. Now we don't have as much of a collective action. Once the civil rights movement reached its peak and we got desegregation, some integration, our collective anger, our collective activity diminished. Now you say in the book, some I found very interesting that the African-American athletes with all of the money that they have with their disposal got together and organized. They could buy teams, they could own teams, they could control what happens to them. So I know the answer, but I want to hear your reflection on there. Why doesn't this happen? I think it goes right back to what you're saying about

about desegregation, integration. As much as I love Jackie and the hell of a guy he had to be to do that. I think that integration, basically, it through cold water on that whole movement. Because remember the movement from almost our whole sense of survival here has been because of what of us doing stuff together, together, this movement. Why I think that what integration is done is basically, it's kind of create this exclusionary thing and we see it with all our kids. So they say, okay, all right, we're going to take you with this institution, we're going to take you, we're going to take you, and they take you so you have this kind of group of black people who are kind of thinking they're kind of elite because it becomes individual. It becomes rather than the collective, it becomes the individual. And I think that we've had about three decades of individual stuff. And it happens with athletics, I think, is a metaphor of that. The individual thing, me, I've got my foundation, I've got my move, I've got put it in context at a time when you couldn't be there. And White folks didn't want you there,

said you couldn't do it. Someone had to step up and do it. And having been in that situation myself, it is hurtful. I mean, you take a lot. And they say, you do it for the race. Now, the thing that you're talking about, you have to get past your own individual contribution and look at the larger picture. The larger picture being that even though some blacks have been allowed to move into sports industry, into medicine and education, still there is a barrier, sort of a cultural and economic barrier that keeps African Americans from moving into the mainstream in the direct proportion. Why is it that in New York City, only 3% of the firemen are black? Now, that's institutional racism. It's not anything that's aimed at Bill Rodden, around school, minus institutional racism. How do you deal with that? And when you deal with

that, collectively, you do sometimes lose your ability to penetrate. What you say, I'm in a collective thing, you don't want to talk to Bill Rodden, because Bill Rodden is a troublemaker. And that's the kind of thing that plays off. So how do we get people to go past that idea that when you work together, you're a troublemaker? That's the million now, the question. Because really, and in sports, I keep saying, and sports is sort of this great metaphor for that, because even in the NBA, when you look and you see 70% of the players are African American, as soon as you start moving off the court, it gets into, it might as well be the police department, or the fire department, because we talk about vice presidents, the power positions, the people who call the shots. It's like maybe 1% Black, if that, and that's a lot. And I'm talking about, if you go into marketing, advertising, vertically, horizontally,

and the questions, how do we do this? And I think that's going to be the question of the 21st century, is what constitutes winning in the 21st century? When you were 16 years old, let's just go back to when you were 16. If somebody would have told you, Roscoe, there's going to be, the owner of the team that's going to be a Black billionaire, he's going to own a professional sports team, there's going to be a guy named Michael Jordan who's going to have all these advertisers. If somebody was laid out where you are now, you would figure, wow, I'd get back to the field because we got home. But then you get there and say, wow, it's another trick bag, because although you got this, this, this, it's all individual. It's not, you've got more Black men in prison than you do in college. You know, so it's although individual, and that's why I get back individually, it's okay, but collectively, we're losing. I mean, you know what I'm saying? So I, in the way, I saw this book almost as a, as a team meeting, you know, you're on a team,

and you guys, you got all the components to have a great team, but you start off all in 10. And so you said, wait a minute, you call a team meeting, no coaches, no, you know, just players, listen, you're the rookie of the year, you're that lead score, you're the lead rebound, but yet we're all in 17, something's not right. And with Black people, that's what I'm saying, you're a particular athlete, we've got more money than ever before, more compensation, but we're losing, something's not right. Well, let's get into the role of the media, and particularly the role of African Americans in the media. There are a few African Americans who have penetrated to high places in the media, and you have an opportunity to write, you have an opportunity to raise consciousness. To what extent does what you write impact on African Americans in terms of their willingness to challenge the system? And to what extent does it cause white to really recognize

just how racist the system has been? To what extent do those things happen? I think that what I find out about the latter point, I just think there's a blindness there, you know, in terms of white's reckoning. I mean, it's almost like being the right to a guy, you lose perspective. I mean, you can't see it, you know, and you just become, you know, there's no content. And I've been just more focused in trying to mobilize African American people. I mean, all people of goodwill understand from that, you can't have a country that claims to be the great democracy with the distribution of wealth being out of whack like it is now. So I think there are a lot of people who understand that this, you know, it's just not, but see, you hit on something that might be possible, and I know in some of our revolution days we talked about it, poor white folks don't do so well in this country either. The gap between the rich and poor white or black is tremendous,

and the question is, how do you get people who have similar needs to come together? Because with 10% of the population, African Americans all have 10% of whatever the distribution is. Actually, we have 1% or 1, 10th of them, 1%. So when you write this, what kind of reaction do you get from other black folks about what you're writing? Well, I think this book will probably be the litmus test. I think there are a lot of, you know, I was on a panel with this, with a basketball play in E-time Thomas, you know, who's with a Washington Williams. He's been very outspoken against the war and all that. He was saying that when he did war, anti-war demonstration, so during the game, a couple of guys come up and say, yeah, E-time, that's pretty good, man, I really was down. But now they would never say it publicly. You know, and I think that's kind of the way it is, because everybody's got their, you know, people have jobs, you want to protect and that kind of stuff. But you know, going back to what you're saying though, and it's something

we've seen kind of before the show about, yeah, there are a lot of white people who are in the same predicament. But because the system has managed to have them listed, just being white, the mere fact of whiteness gives you a leg up, you know, so that's your, that's your piece of the piece of the pie. So I think a lot of those people who really should kind of join together with freedom movements, they kind of say, well, no, I can't really be down with black people because, you know, we're better than that. They were really hard. You're just, yeah, that's the great thing about Kurt Flood. Remember Kurt Flood went and he was the one who broke themselves. And he said, listen, he said, we're all on a plantation. And a lot of white players kind of were stopped, because they had never really understood that, that you may be in the big house. And I mean, we feel, but we're all on the same plantation. And that's when that's why the house came tumbling down. And I think the people in power understand that too, if there was ever that kind of understand people that we're all on this plantation, nobody's free. I think that's when you're

going to have the really beginning of, well, something happened with the unions. Remember, athletes were not unionized 30, 40 years ago. And so the union began to put the athletes in a position where they could front the management. And it has created these millionaires you're talking about. But it hasn't gone to the next level in terms of decision-making and involvement and ownership. Now, what's your next book? I'm actually doing, it's kind of finished. It's a oral history of black quarterbacks. It has been really fascinating. Now why did you take black quarterbacks? Because that position, probably more so than any other position of any other sport in the world. That position, I think, and the lack of blacks playing that position, I think, speaks in many ways to last up. We've been talking about just about how we're not seen as leaders. We're not seen as people who rally the people. And we're in 2006. And it's still a phenomenon.

I mean, we're still talking about hoping that we can get our third black quarterback in the league. I mean, even with Vince Young. You know, you look at Vince Young and this guy, everybody's watching the USC Texas game. This is phenomenal. This is phenomenal. This is for now. We figured the draft was done the next day. He'd be number one. But all of a sudden, after about a couple of months, we started hearing about his test, you know, the Wonder Lake test. And he's got low score and has else seen, he's just an unbelievable. I mean, you know, so it hasn't really ended. So it's, to me, studying, and I'm going all the way back to that thing at Syracuse, George, Tala Ferro, you know, all the way to, you know, James Harrison, Joe Gilliam. And, you know, it's still a very interesting study. And to talk to these guys, man, it's been very, you know, it's almost like, as I was talking to Steve Yearman in terms of talking to his group of people who exceptionally talented. And, but for the color of their skin, could have done extraordinary things. And so it's, it's, it's, I think it's, it's a great

American tale of, um, of race and overcome your book. I know it's been on the New York Times bestseller list. How can the public access it? Is there a website where they can purchase a book or bookstore? You're Barnes and Noble? Barnes and Noble? Barnes and Noble? Human bookstore and Noble? Go to Human bookstore. And I go to your local black bookstore. Right. Right. But if it's one of that close, you go to Barnes and Noble, and you're going to the way I've been, you know, um, Amazon. It becomes a close to the show. What advice would you have for African-American men and women who want to get into sports journalism? Um, it's a great field, uh, be ready for a long hard fight. Um, you know, tell me about that long hard fight. What are some of the elements that long hard fight, man? It's just, they're not a lot of us in this field. Right. And, uh, it's, it's a great gig. It's one of the

latest, the last country club in the newsroom that and being the foreign correspondent, which is why it's so hard to get in. Just think about it. You love sports and you love to write. That's what you do 365 days. But yeah, you go with sports and event. You know, I wrote a comment on the day, you know, keep Joe, you know, by Joe Torre. Yeah. And I mean, that's, you can pay for that, you know, and you can pay to, to watch the meta. So it's a great gig. And, and it's, people really covetous about that. Um, I think that, um, the way to get, it's, you know, it's, it's, it's, it's, it's another show. You know, but if you, if you know black journalists, if you see one, whether it's me or Mike, we'll get the call of, call me at the New York Times, you know, call, just call them, say, listen, you know, um, you know, um, you know, um, brother, since I want to get in this business, you know, could you, you know, I want to give you a mailing address. How do I start? How do they start? Um, how did you start? I started the Afro, I started, I started the Afro American newspaper in Baltimore, because you went to Baltimore,

I went to Baltimore, and my, my, my, my mentor was Sam Lacy, uh, the great sports editor of the, uh, the Afro American news, uh, since 1942, I started the Afro American newspaper. I was a sports information director, assistant, sports information at Morgan. I was, I was always writing for the school newspaper. I was writing for the high school newspaper, you know, and I felt when I finally got paid for, I, I said, what do you mean, you get paid for this? I probably felt to say, well, some athletes do. I guess getting close, somehow getting your foot in the door. And now, although newspapers are beginning to kind of be dinosaurs, uh, I think now with the web and with blogging and with the internet, I think that there's been this whole other world that's opened up, that's kind of not necessarily writing for it. You can just, what you can do among yourself, so you're a group of people. You know, the only thing you need is access. You need credentials to watch the games, but I think that although the newspaper industry might be shutting down and shrinking,

I think in this whole industry of, of blogging and, and podcast and that kind of stuff, the possibilities are really endless. Um, we just have to figure out how we can make a myth, but I think that, um, you know, journalism is where, where you are. And I think now, I mean, you, you've got stuff today in terms of getting messages out there that, you know, remember, we come, I mean, you know, if you didn't write for the, you know, a newspaper, somebody could see it, it didn't exist. You talked about getting messages out there. As a sports journalist, do you really try to get a message or you try to reflect what's happening in the sports world? Both. Well, I think, I think it's, I think it's to me as both, as you could tell, I'm kind of opinionated and, and could talk. Um, to me, it's, it's, it's about, it's about the message. It's about reflecting. It's about reflecting. You know, I mean, when something is, it's about, you know, it's not so much, it's reflecting, but putting everything in some type of perspective. I think

some things demand very little perspective. Some things demand great perspective. And I think the older you get, the more, the more perspective you have, if you're not an idiot, you know, but I think, and I think that's the, the wonder, that's the great thing about, you know, aging gracefully, as you have done, as hopefully I'm in the process of doing, is that your, your, your, your, your, your context continues to expand. If, if you just keep your eyes open, so, and I think being a columnist gives you that sort of latitude to do that, but you do have to, it's not just about sports. You know, you gotta, it's not, it's about the world, it's about the societies, about personality. Today on African American legend, we've been talking with Bill Rodin, the author of $40 million slaves, and he's given us a great perspective on the role of sports in the United States of America and the world. Thanks for being with us today, Bill.

Rascal, thanks for having me. Okay, bud.

- Series

- African American Legends

- Contributing Organization

- CUNY TV (New York, New York)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip/522-sb3ws8jp20

- NOLA Code

- AAL 026014

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip/522-sb3ws8jp20).

- Description

- Series Description

- African-American Legends profiles prominent African-Americans in the arts, in politics, the social sciences, sports, community service, and business. The program is hosted by Dr. Roscoe C. Brown, Jr., Director of the Center for Urban Education Policy at the CUNY Graduate Center, and a former President of Bronx Community College.

- Description

- Host Dr. Roscoe C. Brown is joined by New York Times sportswriter William C. Rhoden to discuss his new book "Forty Million Dollar Slaves: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Black Athlete." Taped October 11, 2006.

- Description

- Taped October 11, 2006

- Created Date

- 2006-10-11

- Asset type

- Episode

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:27:17

- Credits

-

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

CUNY TV

Identifier: 10890 (li_serial)

Duration: 00:27:16:28

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “African American Legends; William C. Rhoden, Sports Journalist, New York Times,” 2006-10-11, CUNY TV, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed January 7, 2026, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-522-sb3ws8jp20.

- MLA: “African American Legends; William C. Rhoden, Sports Journalist, New York Times.” 2006-10-11. CUNY TV, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. January 7, 2026. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-522-sb3ws8jp20>.

- APA: African American Legends; William C. Rhoden, Sports Journalist, New York Times. Boston, MA: CUNY TV, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-522-sb3ws8jp20