The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour

- Transcript

Intro

ROBERT MacNEIL: Good evening. These are today's top news headlines. Final figures for 1985 show economic growth slower than expected. President Reagan gave new backing to opponents of abortion. Student loan applications will be screened for draft avoiders. Details of these stories in our news summary coming up. Judy Woodruff is in Washington tonight. Judy?

JUDY WOODRUFF: After the news summary we have four major focuses on the NewsHour tonight. First, what role should politics play in making grants to colleges? Two university presidents who disagree will join us. Then, a report on the latest tactics by anti-abortion forces. Next, the nation's second-largest bank in trouble; two Bank of America officials join us to talk about its financial problems and charges of money-laundering. Finally, a documentary report on a controversial experimental way of treating cancer. News Summary

MacNEIL: Final government figures for 1985 were released today and they showed a much slower rate of economic growth for the last quarter than expected. From October to December the gross national product grew 2.4 instead of the 3.2 projected by the Commerce Department a month ago. That made the economic growth rate for the whole year 2.3 , slightly down from previous estimates. The inflation rate held steady in 1985. Final figures showed that the consumer price index rose 3.8 over the year. That is the fourth year in a row that it's been under 4 . Judy?

WOODRUFF: The Selective Service System announced today that it's come up with a new way to track down young men who avoid signing up for the draft. In addition to Social Security files and driver's license information, the agency will also now have access to the names of all those who apply for college loans. The announcement was made jointly with the U.S. Department of Education, which will make the names available to the Selective Service. Education Secretary William Bennett defended the move.

WILLIAM BENNETT, Education Secretary: One of the ways in which college students can pull their weight and fulfill their responsibilities of citizenship is by standing ready to defend their country in time of need. Those who expect to receive benefits such as federal student financial aid should be the first to comply with laws requiring registration for the Selective Service System. This agreement between the Selective Service and the Department of Education will not only protect the federal taxpayer; it will also fulfill our obligation to those millions of fine young men who have registered to serve their country if they are ever needed.

MacNEIL: Opponents of abortion today marked the 13th anniversary of the Supreme Court decision legalizing abortion and picked up fresh encouragement from President Reagan. The crowd, estimated at more than 35,000, rallied on the field behind the White House. The President didn't make a personal appearance but spoke to the gathering by a special telephone hookup.

Pres. RONALD REAGAN [by telephone]: A child in the womb is simply what each of us once was, a very young, very small, dependent and very vulnerable live member of the human family. In my State of the Union address I stated that abortion is either the taking of human life or it isn't, and if it is, medical technology is increasingly showing it is, it must be stopped.

MacNEIL: From the White House the demonstrators turned their attention two miles up Capitol Hill to the Supreme Court, focal point of the protest because of its ruling which legalized abortions in 1973.

WOODRUFF: The Supreme Court today gave a shot in the arm to the so-called non-bank banks, those institutions that offer either checking accounts or commercial loans but not both. The court ruled unanimously that the Federal Reserve may not regulate them so as to limit their growth. Supporters of the banks say they offer the public a greater variety of services and create more competition in the financial industry. Opponents say it's dangerous to let these banks operate with the freedom other banks do when they are providing only limited services.

MacNEIL: In India, three Sikhs were convicted and sentenced to death for the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in 1984. One was found guilty of firing the shot and the other two of conspiracy. The defense lawyers said they will appeal the verdicts to a higher court.

Also in India, a Canadian government official testified that a draft report by Canadian investigators says a bomb explosion caused the crash of an Air India plane off Ireland last June. Indian investigators have theorized that a bomb was planted on the plane by Sikh extremists. All 329 people on board the plane were killed.

WOODRUFF: Racial violence flared again yesterday in South Africa. Riot patrols near Johannesburg shot dead at least seven blacks and wounded 40 others after two white policemen were killed trying to break up an illegal outdoor meeting of black gold miners. We have a report from Michael Buerk of the BBC.

MICHAEL BUERK (BBC) [voice-over]: It was the worst incident involving white policemen in nearly two years of black protest violence here. The response was predictable. Police and troops poured into the township this morning in what was both a search for the killers and a deliberate show of force. The two policemen had been investigating an illegal gathering of black miners. They were caught by a mob who tried to burn them before hacking them to death. Only a handful of the thousand people who have died in unrest here in the last 18 months have been white. Police and troops took Bekkersdal Township apart. Dozens of blacks were arrested and taken away under armed guard.

MacNEIL: The U.S. government is investigating the spending of American aid funds in the Philippines because of reports that President Marcos and his family have transferred millions of dollars to investments in the United States. State Department spokesman Bernard Kalb said an audit team from the General Accounting Office would report late in February, after February 7th, when President Marcos is running for re-election. He said so far the U.S. was not aware of any documented evidence that would link U.S. aid dollars to overseas investments by Marcos. The Philippines' acting foreign minister, Pacifico Castro, said today that congressional hearings on alleged money transfers by Marcos were an attempt to influence the upcoming election. Castro spoke at the National Press Club.

PACIFICO CASTRO, Philippine Foreign Minister: The issue of hidden wealth was debated in the National Assembly in the Philippines when a group of opposition members filed a resolution of impeachment. And during the hearings not a single piece of document, not a single iota of evidence had been presented to support these allegations. I understand that this committee of these good congressmen has been conducting hearings of more than 100 hours now, and in the same forum not a single iota of evidence that would stand the test of judicial fairness has been presented at all.

MacNEIL: Finally in the news, at least 12 people were injured when a United Airlines DC-8 hit severe turbulence today. The plane, carrying 138 passengers and a crew of six from Chicago to San Francisco, nosed up and dropped sharply over Utah. It landed safely in San Francisco without serious damage.

WOODRUFF: That concludes our news summary. Still ahead on the NewsHour, a debate over what role politics should play in grants to colleges and universities, the latest tactics being used by anti-abortion forces, the financial headaches that have the nation's second-largest banks seeing red, and a documentary on a controversial experimental cancer treatment. Grant Politics

MacNEIL: At a time when federal dollars are harder and harder to come by, it's almost unheard offor someone to turn down money from the government, but that's exactly what Cornell University did recently. Cornell's president, Frank Rhodes, refused a $10-million grant from Congress to buy an advanced computer that he really wanted. He says he did it on principle, in protest against what he calls political interference in the awarding of research funds. Dr. Rhodes is with us tonight to tell us more.

Why precisely did you refuse the $10 million?

FRANK RHODES: We haven't refused it altogether but we have said that we do not wish to accept federal funding which doesn't involve the merit review of the proposal that's being considered. We've applied for $10 million to fund just the supercomputer that was suggested, but we hope we're still going to get it as a result of a merit review within the Department of Defense.

MacNEIL: What is a merit review?

Dr. RHODES: There's a limited amount of federal funding for science, as there is for everything else. We believe that review is required to make sure that the funds go to those institutions that are best equipped, best qualified to carry out the research. That's generally done by internal panels within federal agencies making that decision, often with the help of external scientists, especially from industry and from government, to give their assessment.

MacNEIL: What's wrong with taking the money from Congress if Congress has decided that you are fit to receive this?

Dr. RHODES: Congress has a major responsibility to fund federal projects, to decide which areas federal support should be used for. The development of a supercomputer which Cornell and three other universities have is part of that general decision. But where that work should be done, the kind of programs that should be developed, that's best carried out by a judgment of informed peers, by a merit review based on the qualifications of the instutions themselves.

MacNEIL: What harm does it do if it doesn't happen that way, if it doesn't go through that route? Who is being harmed or what is being harmed?

Dr. RHODES: Everybody loses. The nation loses, science loses. The nation loses in the end because this isn't just a squabble between higher education and Washington. All the major higher education associations in Washington have come out in favor of this merit review. It's a question of future survival for the nation, because on the best science that we can produce depends our economic competitiveness, our defense, the national quality of our life. It's a major concern that the funds that are available should be used for the best projects.

MacNEIL: And you're arguing that if they are the subject of congressional maneuvering and lobbying and so on, some of them will go to places that won't conduct good research?

Dr. RHODES: I think there's the possibility of that happening. But the probability is that if we get informed judgment, informed review by those who are most familiar with the research involved, we shall get better results in the long run.

MacNEIL: Isn't it true that the federal money that was being allocated for research awarded through the peer review or merit review process has largely dried up under government cutbacks, and that congressional funding in this manner is a substitute for that?

Dr. RHODES: Well, there are two kinds of science projects involved. There are facilities and equipment in which and by which research is carried out, and then there is support for particular research programs. Federal funding hasn't dried up for the grants needed for research programs. It has dried up, and we face a veryserious crisis, in fact, to support the building of new facilities and purchase of equipment.

MacNEIL: What I don't understand completely, President Rhodes, is that you've refused the money but that you haven't refused it. Would you explain that?

Dr. RHODES: We've said quite simply that our need -- and we put in an application based on our need some months ago -- our need remains. If we are to be funded, however, we think it's in the best interests not just of U.S. science but of the nation that the decision should be made on the basis of those capable of judging the quality of our work.

MacNEIL: So you want the $10 million that Congress is offering you for a supercomputer sent back to Washington and routed through a peer review process which could decide Cornell doesn't deserve it.

Dr. RHODES: Right. That's one possible outcome, and the Department of Defense, we're told, and we're delighted to learn this, is about to conduct just such a merit review in which we would be one competitor.

MacNEIL: I see. Judy?

WOODRUFF: Not everyone thinks it's such a bad idea to mix science and politics. Boston University is one of the few academic centers that has hired a lobbyist to look out for its interests on Capitol Hill. The president of Boston University is John Silber, who joins us tonight from public station WGBH in Boston. Dr. Silber, what do you think of Cornell's decision to turn down this money that Congress has voted?

JOHN SILBER: Well, first of all, I'm not representing one of the few universities that has hired a lobbyist. Cornell has some of the most effective lobbyists in the United States. Professor Kenneth Wilson, who was so ie up with the supercomputer and also to work with the NSF on the importance of granting one of those facilities to Cornell along with his colleague from Princeton, Professor Orszag, are splendid lobbyists. There are many lobbyists, presidents of universities, faculty members, and others. So there's nothing unusual about lobbying the Congress. This is the way we get their attention.

WOODRUFF: I think I was referring to the fact of a hired lobbyist.

Dr. SILBER: Nearly all major universities open offices in Washington in which they hire people, usually former staff members of the Hill, to be their lobbyists. It may not be an independent lobbying firm, but they are lobbyists. They may not be as good as some of the professional lobbying firms, but that's not what the universities that hired their lobbying on their own think. Now, as a matter of fact, Cornell does not follow the principle consistently, and I don't blame them. They receive all kinds of money from the federal government through the Agricultural Department, as a land grant college, that hasn't been peer-reviewed by anybody. They have two line items in the legislature, one that was granted last year, $5 million for a food lab and another one that's up this year, a $20-million proposal for a biotechnology center at Cornell, through their state university. I don't blame them for that. I think that's an excellent idea. But let's not overlook the fact that that's lobbying and let's not overlook the fact that that doesn't involve peer review. As a matter of fact, Cornell is a great university, and I dare say that the Department of Defense, when they operate through the old-boy network on their merit review process, will discover that Cornell, which has been highly successful in the past in getting grants, is still going to be highly successful.

WOODRUFF: What about Dr. Rhodes' point, Dr. Silber, that the money that Congress may channel to a university may not end up -- I mean, this is what he suggested, may not end up in a place that's going to do the best research.

Dr. SILBER: Well, as a matter of fact, at the time that Einstein did his most important work he was working as a clerk in a small customs office in Switzerland, and the University of Berlin was probably the greatest university in the world, or one of them, at that time. That great research in physics wasn't going on in Berlin. It was going on in a minor public bureaucratic office in Switzerland. As a matter of fact, there is no monopoly on invention; there is no monopoly on discovery, and it is very important that the Congress not put all the eggs in one basket, because when they establish great facilities in other locations in this country the great scientists are instantly attracted to those facilities. If you were to put a supercomputer in Timbuktu, within a matter of two years you would have a great program with great scientists hovering about Timbuktu working with that great equipment.

WOODRUFF: Let me just ask you a question about your lobbyist. What does this organization, this lobbying organization or office in Washington do for you?

Dr. SILBER: Well, it provides expert services in identifying the members of the Congress who serve on critical committees in precisely the same way that Kenneth Wilson did this for Cornell. There's no great difference on that.

WOODRUFF: Dr. Silber, stay with us. Thank you.

Dr. SILBER: All right.

MacNEIL: Dr. Rhodes, he says Cornell has lots of effective lobbyists. He named them and some of the things they've achieved.

Dr. RHODES: My good friend John Silber named one, and I'm glad he recognized him by name. Ken Wilson, who is a professor at Cornell, is a Nobel laureate in physics, and it's because he's a Nobel laureate in physics that he's such a splended lobbyist. He lobbied in a slightly different way, though, and I think it's worth making the distinction. What he lobbied Congress for was for support for supercomputers. This was a nationwide interest and we were falling behind our economic competitors without them. He was successful, and the Congress appropriated funds for four supercomputers. Where they were located was a separate question, and that was based on merit review. It's that second part that we don't want to leave out of the equation.

MacNEIL: Dr. Silber, by calling it an old-boy network are you saying that merit review or peer review is not necessary or it doesn't work?

Dr. SILBER: No, not at all. I would try to finish up that survey that Frank started. When they finally located the four supercomputers they located one at Cornell with the lobbyist, Wilson; they located another at Princeton with Orzag; they located one in San Diego where the former head of the NSF is located as president. All of them went to universities that have lobbied hard to get the program. They lobbied to get the program and then, lo and behold, the NSF is so grateful -- and it is an old-boy network -- that they then award them the computer. This is -- the old-boy network is natural, it's a perfectly wholesome human phenomenon, and I like the old-boy network. I intend to get into it on behalf of our own institution. I think the establishment is the establishment because it is exclusive, and the reason why I want to get into the establishment is I know how valuable it is to be a member.

MacNEIL: Dr. Silber also says that you're not consistent. That you do take money without peer review, for instance, the $5 million money for a food lab.

Dr. RHODES: He is very carefully mixing up several different categories, and it's useful to distinguish between them. The $20 million and the $5 million he refers to are state funds. They're not federal funds. And state funds are very carefully reviewed by the state to determine whether or not what's going on is in the interests of the state. There was certainly a merit review for both by state officials in deciding whether or not to fund those projects at Cornell. In the case of the Department of Agriculture, that's applied research. It's not basic research. And you will know probably that the quality of that work nationwide that's come in for very heavy criticism in the last year or two.

MacNEIL: What I'm not sure that I get in all this is how it is harmful to the future of science in this country to have one or other system operating. You're defending the peer review system; Dr. Silber says that's nice but he also wants lobbying in Congress. Dr. Silber, start by telling me, if you're both interested in furthering science in the country and having the best kind of research, why is one system better than the other?

Dr. SILBER: Well, nobody's in favor of getting rid of peer review when it comes to specific scientific proposals and particular selections of which scientists should do it. As a matter of fact, Boston University brings in about $60 million a year in peer-reviewed scientific research. And in the building that was built by the $19-million grant that we have received from the Congress along with about $80 million outside that, we will have scientists, and we have scientists already working there, who get their grants by peer review. But it's just humorous to find out that we decide that peer review is not required by scientists when the state makes the grant, but it is required by scientists if the federal government makes the grant. The same process by which Cornell is successful in getting one $5-million project and another $20-million project by review of the legislature of the state of New York is quite analogous to the way in which Boston University picked up $9 million by the peer review of members of the Congress, who decided that it's important in maintaining our competitiveness, that a center of scientific and technological excellence be built at Boston University, and also that it serve the economic interests of the area to build on the strengths of high technology in the Boston area and specifically to rebuild Kenmore Square, an area of Boston in which thie science center is located. Now, that is precisely analogous to the kind of merit review that went into the Cornell grants by the legislature.

MacNEIL: How about the point that Dr. Silber made a moment ago? If the Congress decided to put a supercomputer in Timbuktu it would soon be a valid and important center for research?

Dr. RHODES: The basic question seems to me to be whether Timbuktu is the most appropriate place to develop a supercomputer facility. It's very proper that Congress should have a role in the siting of major national facilities.

MacNEIL: But if Congress just decided -- suppose there was nothing else there, which I think is what Dr. Silber was implying. It was a wilderness and in came a supercomputer and a building to house it, that soon it would become because -- of the facility, the scientists would rush there. Therefore, you don't need to send it to a place like Cornell to make it -- to create the kind of research that's necessary.

Dr. RHODES: To fully use a supercomputer you have to have far more than a spot on the earth where you locate it. You need services, you need transport facilities, you need an enormous resource in terms of scientific personnel in a whole variety of different fields, not to mention outstanding libraries with millions of volumes. It would be a classic example of a waste of federal funds to think of locating it in a place that didn't have that kind of backup.

MacNEIL: Dr. Silber?

Dr. SILBER: That's just a to push the analogy to an absurdity. That wasn't my point. My point is that you don't have to locate major facilities in an established location, because if you locate them in a reasonable location that does not have the distinction, the distinguished scientists come after it, as we wll find out when we go ahead with the supercollider. It will not be located in Princeton, and it will not be located in Cornell and it will not be located, in my opinion, in California along the line of the earthquake ridges. It probably will be located in the Middle West or in Texas, and you will be amazed how quickly centers of scientific excellence begin to develop right around there, and the telephone company and other lines are well-established, state-of-the-art methods of tying people into great libraries and into great communications networks.

MacNEIL: Is it your point, Dr. Rhodes, that by letting Congress decide these things that they become the playthings of congressmen or senators who want to put particular things in their states, just as traditional porkbarrel legislation, and that the criteria won't be good for science? Is that it?

Dr. RHODES: I think there's a real possibility that that will happen. The point I've made tonight is not that in any way I condemn Boston University for what it did. It's improving rapidly in the total level of federal support that it receives for research, but if we're to remain ahead competitively, if the health of the nation is to be cared for by the best methods, then funding has to go where the best science is to be done. That's got to involve merit review, and part of the merit will be the geographical situation. But ultimately the alternative to merit is to spread the federal funding between each congressional district in the country, and that's going to really lose the international race.

MacNEIL: Do you have a final comment on that, Dr. Silber?

Dr. SILBER: Yes. Nobody's talking about getting rid of merit. I'm as deeply committed to merit, I believe, as any university president in this counry. But I believe the Congress is perfectly well qualified to decide where to locate major centers for economic and scientific development, and I think they've done a very good job so far in where they've put it. For one thing, they've put it in largely established places, but the only place we can go to expand the old-boy network and to release the creative energies of this country in other areas in developing the South and the Southwest, which have largely been cut off from NSF and NIH research, has been through direct appeals to the Congress. There are all these established universities that find coighteous indignation and on one inconsistent project decide instead of getting it one way they'll get it the other. My bet is Cornell is going to get it.

MacNEIL: Well, Dr. Silber in Boston, thank you; Dr. Rhodes in New York, thank you. Judy?

WOODRUFF: Still to come on the NewsHour, a documentary report on a new approach to halt abortions, hard times for one of America's largest banks, and a look at an experimental cancer treatment that's causing a lot of controversy. Abortion Boycotts

MacNEIL: Today's anti-abortion rally in Washington has become practically an annual tradition since the controversial Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision 13 years ago. In some places, marches, rallies and picketing have had the desired impact, reducing the number of abortions or discouraging doctors and clinics from performing them. In other areas violence has shut down facilities where abortions were performed. In Washington state, pro-life advocates are working on yet another approach to blocking abortions. Victoria Fung of public station KCTS reports.

ANTI-ABORTION DEMONSTRATOR [singing]: "Red and yellow, black and white, they are precious in his sight, Jesus loves the unborn children of the world."

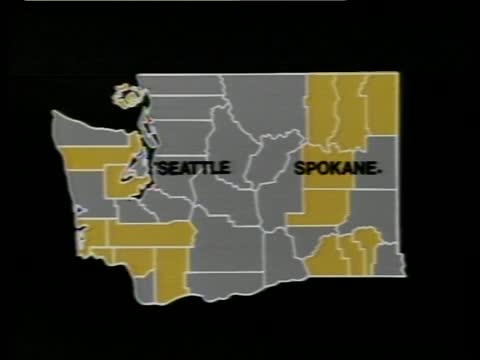

VICTORIA FUNG [voice-over]: After 13 years, protest against abortion is running as strong as ever. So-called pro-life groups have tried a number of tactics to fight the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that legalized abortion in 1973. But abortion remains a legal medical procedure, so pro-life organizations are changing their strategies. If they can't make abortions illegal they want to make them inaccessible. In Washington state, pro-life forces are trying to make each of the 39 counties an abortion-free zone. To start they're pushing doctors and hospitals in small towns and rural areas to quit performing abortions or else face the threat of an economic boycott.

DOTTIE ROBERTS, anti-abortion activist: Doctor by doctor, hospital by hospital and county by county we'll win this war.

FUNG [voice-over]: Dottie Roberts leads the right-to-life movement in Washington state.

Ms. ROBERTS: We have an approach of communication with the doctor where he stands, then we proceed to see that the community is aware of who the abortionists are, and then we provide the kind of followup to encourage people to stop doing business with death doctors. We picket. We picket them at their homes. We picket them at their hospitals and we picket them at their place of business. But that's been the general approach, and that's a very large order.

FUNG [voice-over]: Pro-life groups claim their movement has been very successful. In Washington state abortion services have never been available in 16 counties. Abortion services used to be available in 23 counties. But over the past few years, pro-lifers say they've turned five rural counties into abortion-free zones. A prime target of the pro-life boycott in Washington is General Hospital of Everett, located 30 miles north of Seattle. It's one of the larger hospitals in the state, and it's in the same city where an abortion clinic was repeatedly firebombed and forced out of business two years ago. General Hospital has been under pressure from religious groups. The hospital board was already thinking of discontinuing abortion services when pro-lifers recently fired away with the threat of a boycott. Spokesperson Jean Edwards says the hospital board is still pondering its decision.

JEAN EDWARDS, General Hospital spokesperson: We're trying to be responsible community people, and we're trying to run a responsible community hospital. And we're not the least intimidated by this.

FUNG [voice-over]: Yet Edwards says the hospital is taking the threat of an economic boycott very seriously.

Ms. EDWARDS: I think any person or any group who is trying to run a business, you know, if you are reponsible kind of people at all you take a look at any kind of a threat to your business. And a boycott is one kind of threat.

FUNG [voice-over]: A number of doctors in Everett support the pro-life movement and actually favor a ban on elective abortions. Dr. Kevin Ware backs the ideaof a boycott against General Hospital.

Dr. KEVIN WARE, anti-abortion physician: I would hope that they would realize that the hospital suffers economically because of their stance on the issue, and in that realization I would hope they would change their policy. Ideally I wish they would change their policy on the basis of moral conviction, but failing that they should see it as a business decision. We've notified the hospital, Everett General, that a significant number of our patients would prefer to go elsewhere, given a choice about the matter, unless the hospital changes its policy.

ANNE FENNESSY, pro-choice activist [on telephone]: Nine o'clock we'll go down to Olympia and we're going to have a workshop to learn how to lobby. And then we will be meeting with legislators all afternoon. We'll have a rally --

FUNG [voice-over]: Pro-choice activists are battling against the movement to create abortion-free zones. The Washington chapter of the National Abortion Rights Action League is lobbying more vigorously in support of hospitals and doctors under fire. Executive director Anne Fennessy predicts an economic boycott will fizzle.

Ms. FENNESSY: Of the hospital boards that I've heard from, they are standing very firm with [that] they provide medical services, abortion being one of them, and that they are not going to be pressured to quit performing any kind of medical service that the community asks for. Especially in Washington state. We have a very strong pro-choice tradition. I mean, we are the only state in the country that legalized abortion by the people's vote back in 1970. We're real confident we're going to keep our right.

FUNG [voice-over]: But anti-abortion protests and the threat of a boycott are intimidating pro-choice doctors in Everett, according to Suzanne Poppema, a family-practice physician.

Dr. SUZANNE POPPEMA, pro-choice physician: I think of the physicians that I know who perform terminations of pregnancy I can't think of a single one who would like me to name them. It's being done quietly and discreetly, and I think to some extent more quietly than it needs to be because they're afraid of potential retaliation. People are afraid that something bad is going to happen to them or their car or their clinic. And I think it's an atmosphere of what sounds like paranoia, but isn't paranoia. It's reality.

FUNG [voice-over]: This health clinic in Yakima is one of the last places in central Washington where abortions are still available. The clinic has been a target of continuing protests, but it still performs an average of 1100 abortions a year. Clinic director Kimberly Boyd is angry that women in neighboring counties are being forced to travel long distances to clinics like hers.

KIMBERLY BOYD, Yakima Women's Health Center: Women do have difficulty geographically obtaining an abortion, especially in this area. And I'm sure in a lot of other areas. It does make the abortion more expensive for the woman, and sometimes totally inaccessible.

FUNG [voice-over]: No one knows just how effective an economic boycott against larger abortion facilities will be because it's a relatively new tactic, but right-to-life groups are convinced a boycott will carry them far.

Ms. ROBERTS: I believe so. I intend to invest my time and energies in succeeding at making abortion a thing of the past. Seeing Red

WOODRUFF: Our next focus is a bank with more than its share of problems these days. Word came yesterday that the Bank of America, the nation's second-largest bank, was reporting record year-end losses for 1985 and was being fined almost $5 million by the U.S. Treasury for failing to report large currency transactions. We will look at both developments, but we begin with a look at the bank's financial status. Its losses in 1985 came to $337 million and led the bank's board of directors to cancel dividend payments on its common stock. The bank also reported record loan losses of $1.6 billion, mostly due to lending in real estate and agriculture as well as to developing nations. For more on this we talk with Stephen McLin, Bank of America's senior vice president for strategic planning. He joins us from public station KQED in San Francisco.

Mr. McLin, why losses of that magnitude?

STEPHEN McLIN: Well, Judy, it was a tough year for the bank, and we had concentrations in some of the sectors that you mentioned, in agriculture and shipping loans, in Latin American loans and so forth. But we also had some positive things happen last year. Our capital ratio is up almost $500 million from year-end 1984, and our non-accrual or restructured loans dropped some $500 million from the third quarter to the fourth quarter, and the total was down from 1984. So there were some positive signs among the other figures that you cite.

WOODRUFF: But the overall figure was down, and most of this was due to the bad loans that we mentioned. Again, why bad loans of that enormous size?

Mr. McLIN: Well, as I said, we ended up with some concentrations in some areas, notably agriculture, shipping and real estate, and some of which were viewed a few years ago as a great strength. For example, in agriculture we made loans three or four years ago to finance vineyards in the San Joaquin Valley when the land was valued at $15,000 an acre, and at the time we made a prudent loan of $12,000 on a $15,000 loan per acre. Now you can buy that land for $6,000 an acre. So we have suffered, and unfortunately the farmers have suffered even more than the bank has.

WOODRUFF: What about the foreign loans? We know that that's a big part of what happened. What about that?

Mr. McLIN: Well again, I think all the banks have suffered from this and our exposure and problems in the foreign loans tend to mirror some of the problems that our colleagues in new York and Chicago have had.

WOODRUFF: But we know other banks have made these kind of loans but they haven't ended up with the size loss or writeoff of these loans that you all have ended up with. What's different?

Mr. McLIN: Well, the difference is that we're in more places than most other banks, and when things start to come up, problems, simultaneously we end up suffering more relative to other banks.

WOODRUFF: Did somebody make a mistake? I mean, are fingers being pointed within the organization?

Mr. McLIN: Judy, as I said, I don't think it's an issue of mistakes. In some sense we have strengthened our balance sheet ratios and reduced our problem loans from last year to this year. Unfortunately we had sizable losses to go along with that.

WOODRUFF: But, I mean, is someone responsible for this, or is it just considered fate or whatever? I mean, how do you deal with that?

Mr. McLIN: Well, you know, a lot of factors. Some of it -- disinflation has probably been the biggest factor. I think bankers in the decade of the '70s and early '80s found that inflation tended to bail them out of bad credit decisions, because if you made a real estate loan, even if the credit was not perfect, inflation would increase the value of housing. The agriculture example that I mentioned in wine-growing land, that had been on an upward scale for years, and everybody expected it to continue. So I don't think it's an issue of somebody making a mistake. Nobody has crystal balls to tell us what's going to happen.

WOODRUFF: So as far as the Bank of America is concerned there's no person who's responsible, no heads are going to roll as a result? Is that it?

Mr. McLIN: No heads are going to roll. We're just going to put our head down and get the job done in 1986.

WOODRUFF: Continental Illinois, the name of a large bank that we all know, almost went bankrupt when foreign banks started to lose confidence and began to pull their money out. Could the Bank of America sustain that sort of loss of confidence by foreign banks?

Mr. McLIN: Well, we're in a different situation from Continental, a much better one. We have four million customers in California. We have half a million or 500,000 customers in the state of Washington. They've been loyal to us. They're behind us. The way we've handled their business has been good. We've offered them new products and services over the last couple of years, and those customers have put a lot of money into B of A, and they know their money is safe and that the bank is strong, despite the losses to earnings. Unfortunately our shareholders have taken the brunt of the problems. But in terms of our deposit base everything is on track and we've had no problems there.

WOODRUFF: So the same thing couldn't happen to Bank of America?

Mr. McLIN: No. We rely on core deposits from sort of regular customers, not big jumbo deposits from foreign banks.

WOODRUFF: And the outlook for '86, again, is%%%

Mr. McLIN: Excuse me, Judy?

WOODRUFF: The outlook for '86? I was just asking you to repeat what you said a moment ago. You think it's looking good.

Mr. McLIN: Well, we think -- we're pretty excited about our prospects for '86. We see the trend line as positive, and we're looking forward to showing some good results in 1986.

WOODRUFF: Stephen McLin, thank you for being with us.

Mr. McLIN: Thanks, Judy.

WOODRUFF: Robin?

MacNEIL: Now the other bad news for the Bank of America. As Judy said, the Treasury Department yesterday fined the same bank a record $4.5 million for violating federal currency laws. The bank failed to report more than 17,000 cash transactions, each worth more than $10,000. The fine was the largest civil penalty ever imposed on a bank for this offense, but it's part of a federal crackdown on money laundering, the method drug traffickers and other criminals use to move funds through the banking system. To discuss the currency violations we have George Coombe, the bank's executive vice president and general counsel, also in San Francisco.

Mr. Coombe, how can 17,000 violations of federal law occur without the bank management knowing about it?

GEORGE COOMBE: Well, Robin, I think you have to understand the manner in which these violations do occur and the context within which they occur. The Bank of America is by far, perhaps by a factor of two, the largest retail bank having the most branches in this country. We have a far-flung geographically and also a very complex branching system. Within that system we employ tens of thousands of people. When the act was first passed applicable to domestic transactions primarily in 1970, we immediately reviewed the act, we immediately introduced practices and procedures throughout the system to assure ourselves within management that the act was being followed scrupulously and, to our knowledge, we had very few problems. That act was amended in 1980, Robin, as you know, to include, by way of stricter enforcement, trans-border shipments involving, among other things, the shipment of currency within the bank from one branch, say, in San Francisco to a Hong Kong operation or from the Bank of America in San Francisco to another bank in Hong Kong. As a result we reviewed the new amendments. We sought to interpret those amendments and the accompanying guidelines issued by Treasury and to apply them with revised practices and procedures.

Now, obviously we did not do the best job in attempting to interpret and apply those guidelines. And without attempting to cast aspersions on anyone within the system, I think the second most important point to make is within this large system almost without exception, Robin, our violations have been technical violations. Let me give you an example. The guidelines permit us to exempt certain kinds of business customers and with regard to those particular customers we are not obligated, indeed, we do not report to Treasury any transactions involving currency either coming into the bank or remitted to those customers in excess of $10,000. On the other hand, if the particular customer pursuant to the guideline does not qualify for exemption, we are obligated to count each one of those transactions, to note it, to record it and in turn to report it to the Treasury. Let us take, for example, and it's a common example for us, one of many very valued retail customers, a ski-slope operation. In that case, if it is an ordinary ski-slope operation where most of its income is obtained from ski-lift tickets, that is an exempted business customer. But, Robin, if additional business activity takes place on the premises of that particular customer, for example, the sale of sporting goods or a restaurant and food operation, then, again depending upon the magnitude of that additional activity, that customer may have to be placed on a non-exempt list and he must then record those transactions.

MacNEIL: I see. How do you escape the impression that you and some other banks, because you don't particularly like this law, just sort of turn your eyes away from it and drag your feet about really implementing it vigorously?

Mr. COOMBE: I would not agree with that. Speaking for myself and certainly for the client I represent, the Bank of America, we not only believe in law enforcement, but we've tried our level best over an extended period since 1970 to comply with every aspect of this act. And we understand fully, Robin, the import of that compliance. It's terribly important in a complex world where the Treasury, among other federal law enforcement agencies, is seeking to combat organized crime in a very complex environment. It is very, very important the Treasury enjoy the opportunity to review the leads that are forthcoming when these reports are filed, and we believe in compliance and we believe in the law.

MacNEIL: And we believe in the clock, Mr. Coombe, and I'm going to have to go. Thank you for joining us from San Francisco.

Mr. COOMBE: Thank you, sir. Cure for Sale?

WOODRUFF: Each year tens of thousands of cancer victims volunteer for experimental treatments that may or may not save their lives. But while they are given the chance to take such a gamble, hundreds of others must be turned away, left to wait months, even years for the new treatments to be proven and marketed. For the desperate and dying there was nowhere else to turn until now, as we see in this report by correspondent Tom Bearden.

TOM BEARDEN [voice-over]: Foy Reynolds has colon cancer. For four years now Reynolds has been desperately seeking treatment, any treatment that would halt its deadly spread. Nothing worked for very long. Last summer Reynolds attempted to join an experimental program at the National Cancer Institute. They turned him down.

[interviewing] What did you feel like when they told you at the NCI, National Cancer Institute, that you couldn't get into their program?

FOY REYNOLDS, cancer victim: Well, I was disappointed because it was kind of my last straw. I'd took chemotherapy and had operations and radiation and it was the only chance that I had, really.

BEARDEN [voice-over]: The treatment Reynolds wanted involved the use of a substance called interleuken-2, more commonly called IL-2. It occurs in the body naturally in minute quantities and tends to stimulate the immune system. The results of the NCI IL-2 study were published last month in The New England Journal of Medicine. Scientists had experienced a phenomenal rate of success, almost half of the 25 patients had partial remission of their tumors. The report created an enormous amount of publicity and raised the hopes of hundreds of thousands of cancer victims. The NCI was besieged by people seeking the same treatment.

[interviewing] What has been the worst side effect so far?

[voice-over] Just after Thanksgiving Reynolds, who is 58, began receiving the IL-2 treatments he had tried so hard to get, but not from the National Cancer Institute or any other nationally recognized research institution.

[on camera] Reynolds is participating in a program that is part of a new approach to the treatment of cancer. It's being pioneered by a company called Biotherapeutics located here in Franklin, Tennessee, just outside of Nashville. What is unique is that patients are paying for their own research projects, up to $35,000. And because all of this is experimental, it's not covered by health insurance.

[voice-over] But Foy Reynolds, who is paying Biotherapeutics $19,000 for his IL-2 treatment, says when you're dying money doesn't really matter.

Mr. REYNOLDS: What's money? You can't take it with you, and if you die and got a million dollars, why you're not going to take -- get any use out of it, so you might as well be trying to get cured, is my opinion. And if I had the million and it cost a million more to try something else I would, but I really believe this is my answer to my prayers and everything.

Dr. ROBERT OLDHAM, Biotherapeutics, Inc.: We're saying it's perfectly feasible and reasonable for someone to have research funded on their own behalf, if they choose to, and that's what we do in the company.

BEARDEN [voice-over]: The founder and driving force behind Biotherapeutics is Dr. Robert Oldham. Dr. Oldham has impeccable credentials as a scientist and a researcher. He is the former head of the research division of the National Cancer Institute. There he limited number of patients who were selected to participate in government-subsidized cancer treatment programs. In May he opened Biotherapeutics because he thought more patients should have access to these experimental treatments. He's now handling 40 patients.

Dr. OLDHAM: I think it would be in society's best interest and our patients' best interest if there was both societal research done at the National Cancer Institute and the universities supported by philanthropic money and tax funds in this country, as well as private research primarily supported by the patient and corporations and private philanthropy. I think that sort of approach would broaden our approach to cancer treatment and give thepatient more leverage in the system. Right now the problem, I think, is that the patient has very little leverage.

BEARDEN [voice-over]: Dr. James Holland, a cancer researcher at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York City, argues that scientists should be selective in the patients they choose for experimental programs.

Dr. JAMES HOLLAND, cancer researcher: We cannot take everyone who wants to be in a study. That really has very little to do with it. First a patient has to add -- to accept being in a study, but it isn't because he wants in that he gets in. It's because then the qualities, the characteristics of the disease and the characteristics of the stage of the disease and the other organ functions and the study program we're conducting make it appropriate to study that individual so that we are studying the drug, not just trying to help that individual.

Dr. OLDHAM: That's the reason why you tend to select against the more sick patient, the more advanced patient, the patients where there's a likely difficulty going to develop, particularly very early on. But I think we believe that if patients want to have an opportunity to try something that we'll be a little more liberal of entering them into our studies.

BEARDEN [voice-over]: Dr. Eugene Nakfoor is another one of those who didn't qualify for any cancer research programs. He is a 62-year-old physician from Michigan who suffers from a terminal case of lymphoma. He also came to Biotherapeutics for experimental treatment.

Dr. EUGENE NAKFOOR, cancer victim: Well, there's not a better game in town, is there? When you think about it, where else -- where am I going to turn? I've got a condition that at this point is not curable, I'm at a stage in which the traditional treatments are going to become more harsh and more severe, and so it's my best choice right now.

BEARDEN [voice-over]: Dr. Nakfoor is paying $35,000 for an experimental treatment which uses something called monoclonal antibodies. Monoclonal antibodies, like interleuken-2, harness the body's immune system to fight cancer. Several cancer research programs around the country are experimenting with monoclonals but so far none has reported significant success. Dr. Nakfoor concedes he has mixed emotions about paying for such an unproven treatment.

Dr. NAKFOOR: Yes, I think it brings up a lot of questions in my mind. Should I pay $35,000 to subject myself to research that may not have any benefit for me? And it bothers me from the standpoint I have friends and relatives who couldn't afford the $35,000. And basically in some ways I can't afford it. I'm not a wealthy man.

Dr. NAKFOOR [during examination]: And maybe these glands got bigger again as they seem to do in reaction to these infections.

BEARDEN [voice-over]: In fact, to pay for his research Dr. Nakfoor hd to take out a loan. The prospect of desperate cancer patients funding experimental research bothers many doctors.

Dr. STUART LIND, oncologist: I think they believe in what they're doing, but I think there is this problem with taking desperate patients and asking them to do something that requires money.

BEARDEN [voice-over]: Dr. Stuart Lind is an oncologist at Massachusetts General in Boston. He is also writing an article critical of Biotherapeutics for The New England Journal of Medicine.

Dr. LIND: What happens if you get to the person who almost has enough money, who just has to raise a little? Well, that's not so bad. Nobody's going to suffer, perhaps. Then you get to the people who don't have the money. Well, they'll raiseit. They'll ask their friends. Beyond that you have the tragedies that no one will ever hear about. Somebody spends all their money and leaves their family without any resources and something bad happens after that person dies, and you can just envision a whole chain of events.

BEARDEN [voice-over]: However, Dr. Oldham's partner, Dr. William West, wonders what patients have to lose by seeking out experimental therapies.

Dr. WILLIAM WEST, Biotherapeutics: Many of these patients are told there is nothing that can be done, go home, prepare yourself and enjoy your last days. And a lot of people don't do well with that. They prefer to feel like they're making something positive and creative out of their otherwise difficult experience.

BEARDEN [voice-over]: But some cancer researchers argue that giving patients greater access to experimental programs can make their lives even more difficult. Dr. Paul Bunn heads up cancer research at the University of Colorado health sciences center. He's worried about potential side effects.

Dr. PAUL BUNN, cancer researcher: If interleuken-2 is indiscriminately given to thousands of patients now and none of them benefited and all of them had side effects, that would certainly not be anything that any of us would want.

BEARDEN [voice-over]: It's too soon to know how many Biotherapeutics patients will be helped, but it is certain the success of the company is dependent on whether or not Dr. Oldham's non-traditional approaches to the treatment of cancer prove correct. Perhaps the most radical of Dr. Oldham's concepts is his conviction that a patient's cancer treatment should be custom-designed. That's in dramatic contrast to the standard practice of giving patients fairly uniform doses of chemotherapy or radiation.

Dr. OLDHAM: If you look at cancer as a biological entity -- in other words, what's it like when you examine it -- you find that a cancer that looks the same as another cancer, one patient's alive for five years and another's alive for five months. That tells me that these tumors really are different, one among the other. And I think it requires us to respond to those differences that we can see in the laboratory in designing therapeutic approaches.

BEARDEN: You said earlier that a lot of his arguments made sense when taken individually, but taken all together they don't. Could you be more specific about that?

Dr. LIND: Well, I think it's very possible that individualized therapy is a good idea. It's very possible that monoclonal antibodies which can do all these things will be standard drugs in the next 10 years. It's very true that people who have advaomething about it, and that it's difficult to get grant money. But when you pull the whole package together, what you're doing is telling people who are very desperate that you have something that might work, make them pay for the opportunity to find out.

Dr. OLDHAM: If we knew for sure that what we were doing couldn't work, then clearly we shouldn't do it. And I would challenge anyone to demonstrate that our method is not going to work in advance. I think we're using the same techniques that are used in the programs I set up for the National Cancer Institute, for example. We're just taking those opoprtunities to patients sooner. I think it's open to debate how successful that'll be, and we'll simply have to do it for awhile to know the answer to that. That's the nature of science.

WOODRUFF: The Food and Drug Administration, which regulates the use of drugs, has not given formal approval to the Biotherapeutics program. Dr.Oldham says that's not necessary because each patient's treatment is unique. But the FDA says it is reviewing the matter.

MacNEIL: Tonight's Lurie cartoon looks at OPEC and the decline in oil prices.

[Lurie cartoon -- OPEC minister offers to sell oil at $20 a barrel, but his raft is floating on a glutted sea of oil and he capsizes.]

Again, the day's main stories. Final figures from 1985 show economic growth slower than expected. President Reagan gave new backing to opponents of abortion. Student loan applications will be screened for draft avoiders.

Good night, Judy.

WOODRUFF: Good night, Robin. That's our NewsHour for tonight. We'll be back tomorrow night. I'm Judy Woodruff. Thank you and good night.

- Series

- The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour

- Producing Organization

- NewsHour Productions

- Contributing Organization

- NewsHour Productions (Washington, District of Columbia)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip/507-kk94747k28

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip/507-kk94747k28).

- Description

- Episode Description

- This episode's headline: News Summary; Grant Politics; Abortion Boycotts; Seeing Red; Cure for Sale?. The guests include In New York: FRANK RHODES, President, Cornell University; In Boston: JOHN SILBER, President, Boston University; In San Francisco: STEPHEN McLIN, Bank of America; GEORGE COOMBE, Bank of America; Reports from NewsHour Correspondents: MICHAEL BUERK (BBC), in South Africa; VICTORIA FUNG (KCTS), in Everett, Washington; TOM BEARDEN, in Franklin, Tennessee. Byline: In New York: ROBERT MacNEIL, Executive Editor; In Washington: JUDY WOODRUFF, Associate Editor

- Date

- 1986-01-22

- Asset type

- Episode

- Topics

- Economics

- Education

- Social Issues

- Women

- History

- Film and Television

- Health

- Consumer Affairs and Advocacy

- Politics and Government

- Rights

- Copyright NewsHour Productions, LLC. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode)

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:59:53

- Credits

-

-

Producing Organization: NewsHour Productions

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

NewsHour Productions

Identifier: NH-0607 (NH Show Code)

Format: 1 inch videotape

Generation: Master

Duration: 01:00:00;00

-

NewsHour Productions

Identifier: NH-19860122 (NH Air Date)

Format: U-matic

Generation: Preservation

Duration: 01:00:00;00

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour,” 1986-01-22, NewsHour Productions, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed January 25, 2026, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-507-kk94747k28.

- MLA: “The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour.” 1986-01-22. NewsHour Productions, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. January 25, 2026. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-507-kk94747k28>.

- APA: The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour. Boston, MA: NewsHour Productions, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-507-kk94747k28