At Howard; 109; John Hope Franklin

- Transcript

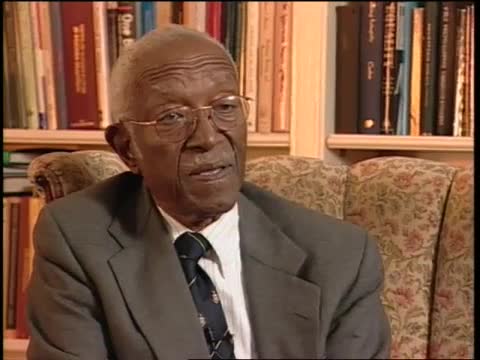

You. Have. To Hello I'm Patrick Swygert and you are at Howard when Dr. John Hope Franklin talks of history. He knows of what he speaks for more than five decades as one of the premier thinkers of our times. He's challenged what the world knows of our communities of color. He's peeled back layers of ignorance and he has helped make sense of many of the stories of the African-American experience. On this edition of at Howard former Virginia governor and Howard graduate Douglas Wilder and Howard University Professor Joseph Harris are in conversation with historian Dr. John Hope Franklin. Dr. Frank let me thank you for this opportunity to share in some of the history of

our country to be hosting your home is a great honor for all of us. And I know I speak for a great number of Americans when I say I'm speaking to living history walking history and you're continuing to provide so much research and so much opportunity for others to learn about what we are. I'm so delighted that you have taken the initiative in this very important project. I think that until we really get to understand slavery what is meant to this country. How this country has fared and what impact it has had on the economy of the country. And on the psychology of the country its outlook its way of thinking about all kinds of things not only political but economic and social and so forth

until we get to understand precisely what the institution of slavery has meant to this country and has done to this country. I don't think we can move forward in the way this country deserves to move forward. I couldn't agree with you more. I consider it the nexus between who we are who we were and who we might be right. Because there's so much ignorance relative to what it was about. It's Hollywood hasn't done the job. Schools haven't done the job. Negro history as they called it. When I was coming up as a boy or as an elective in high school you didn't even have to learn it. But it's not it's it's just not Negro history for that matter and it's black history. It is American history. Absolutely and that's what we have to remember. We can we can talk all we want about African-American history. But we are taught when we do that. We're talking also about American history

that. We cannot forget the relationship say of George Washington to this history or Thomas Jefferson James Monroe or James Madison or any of you. Yes. Yes that's true. That's true and that's what we have to remember. And every time they took a breath it was in terms of their connection with our relationship to the institution of slavery or individual slaves they thought and lived and breathed that every day of their lives. Now it seems to me we have to we have to think in that context as as as as Americans we have to think in that context before we can understand. Where we've been and where we've gone. Oh I agree with you. And I think further that to the extent that we discuss it and have our children discuss it their children discuss it and pass it on from generation to

generation. As you know when we were coming up people didn't want to even talk about it because it was shame. Well that's still true to a considerable extent to the extent that it should not be true it's still true. And I can understand that I don't agree with it but I can understand how people want to shake. A pastor that they think was degrading humiliating and so will they want to get beyond that and they want to talk about what they can do and who they are and what they can be. But they can't do that without recognizing who they are and where they came from what they have been up to this point then they can move forward. Then the nation can move forward and promoting a better understanding and a better relationship and a better position. For all Americans. And this whole area I think you're absolutely

right which touches on the very next thing and that is when we discuss things like this in the context of American history actually is world history too just as it is. Sure. To the extent that we do that we are not fixing blame. Establishing guilt or trying to exact anything at all other than to get the truth and some don't want to see that happen. And you've been involved with it for so long in terms of writing about the history of this nation as well as others across the world. What do you think to me the main cause for that so-called leave it alone theory exists and I know what you've just said but how can we avoid it. Well I think we can avoid it. We can avoid this particular mindset and this attitude we have if we could learn exactly what it was. And what it represents.

And even the role that slaves paid played in the history of this country and in their own effort to become free by last book with my with a colleague of mine former the man was on runaway slaves. And it shows the great tribe which slaves had in themselves and their determination not to be slaves. For the remainder of their lives and for their children not to be slaves. I am so moved when I read about. Mothers and fathers. Running away steeling themselves. And running away with their children sometimes children who are so young that it was dangerous indeed it was reckless in a sense for them to be moved through the night into the light of freedom in some some parts of this country. And yet it was done over and over and over again.

I reminded the fact too that what we call in it's current Now what we call House say I like to use it as a house slave and there is the impression that brother that they betrayed their own race. You know they betrayed themselves by kow towing to their owners. This was not true. And we have numbers and numbers of examples. Of how slaves who poisoned their owners who stole from their owners. Who ran away from their owners never to return and the owners would say sometimes in the end the ads which they say were trying to get them back I don't know understood I don't want to say why they left. After all they were he was my butler. She was our favorite maid or she was our cook but those characters those those

blacks are gone. They have absconded and it shows you that not even if they were getting favors even they even if they were the favorite slaves it wasn't enough for them. They said we want out of here and they got out of there. We have to learn if we're going to overcome this this shame that some of us have out of them. But some of us have because then we have to know exactly what happened during the during the slave period and we then we can we can smile and take pride as a yes. My great great to The Nth Degree. Grandmother was not satisfied as a house as a house maid. She left that place. Or she committed a crime such as poisoning to get away so that when we when we learn about the past we mean what slaves did

both how slaves and feel slaves then we will I think begin to straighten ourselves up and have some pride and some appreciation for what they did and then we won't turn our heads away from this period in our history. We will say yes that was a good period because people were struggling to be free even then even when their own struggles to be free from England said no you can't have what we have you can't have that kind of freedom. It's for us not for you. They said Oh no yes it is for us. That's what they will say. Even as they volunteered to fight in the war for independence and George Washington told no get back. You know this is not for you to say oh yes it is. It's for us. And before long Washington admitted it was for them because when he saw what was happening to them he said I'll take you I'll take any

of you and promise you your freedom if you come and help us get out from under the cover of England so that we've got you've got a glorious and illustrious past. It simply has been distorted and obscured by historians by our contemporaries to the point that has brainwashed us to the point that we don't believe in ourselves. There's always been this effort to divide us whether it was skin color whether it was have texture whether it was feeling and whether it was House and whether you were to the mountain born. And sometimes we fall into that trap but unfortunately also other than African-Americans believe we should say nothing about it. That was passed. Forget it don't talk about it. And yet the other groups constantly remind of what took place and I can't help but bring up the situation of the Holocaust Museum which exist in this country to remind people as to

what took place not in this country but some other place to show the plight of the Jew and how the Jews survived and how they will never repeat that again. To the extent that we tell our story as eloquently as can be and no person could be more eloquently descriptive of it than yourself to be in that position to be in that posture to benefit by what you have to give and to pass it on to generations through the museum of the type that we are putting up is the very essence of what we stand for the spirit of telling about the story of America. Well I can remember to the time when you said I'm in your office when you were governor. And began to talk about this. And it was my view that it ought to be as graphic. And as clear. And unequivocal and as honest as it possibly could be. And I have followed with great interest. The evolution of this idea

into what I hope will be a reality in the not too distant future. Where all Americans will have the opportunity as they do in other museums and truly to hold the Holocaust Museum to learn about what had have what happened what actually has happened. And I'm I'm hopeful that the museum that the National Slavery Museum. Will fill in that very important niche of place in our history that has up to this point been. Sort of blank or not been vague and not fully and dramatically represented. I believe that this museum can contribute greatly to the understanding of the past. And can contribute greatly to planning for the future for we will if we plan for the future without the impediments.

And without the obstacles presented by the institution of slavery. And if we can plant an understanding of how that facilitated the evolution of this country to the point that it is today then I think we will all be much more prideful of their late period despite the fact it was man's inhumanity to man. We can very appreciate very much appreciate exactly what that is done to make this country great. What are the reasons that we are here today is to help with that message. You're saying the things that you're saying carrying forth the word that should be cared for. And as I repeat as often as I can with the view toward education to the extent that our youngsters can start out now and not just the African-American youngsters all go to learn what this nation is about. How did it come to be and how are we part of the solution that we exist.

You know I doubt that there's any. Any area or aspect of American life. To which African-Americans did not contribute. Take for example the cuisine. We sometimes forget that first of all it was Africans who taught Englishman. How to how to use rights how to plant rice and harvest how to how to cultivate and harvest and harvest it and then you can imagine the impact that that had on the on the cuisine not merely of Southerners but of all people and all over the country. That's just one tiny example. You think you think people in the south coming in from from England know anything about rice culture yet not only was it

a very significant part of the diet and cuisine but it became a very very important thing commercially. And people from West Africa tell them all about it and that's just one example. Dozens of them from every aspect of it and facet of life so that I think that once we know this what's what is known abroad and known by everybody we can't help but have a different attitude. Toward slavery and toward the people participating in slavery. They won't say go back to where you came from. They won't say that anymore because this is as you say and you might you might respond. Well I'll take my mom was to go. Dr. Franklin when we were in the mansion we were talking about

any number of things and Earlier we talked a bit about the slave ship. Tell us when that evening to spy what may have been the grounds of Jamestown how you envisioned issue. You know. I believe that. The people of this country need. The most graphic and. Direct. Illustrations clear illustrations. Of slavery that they can have including the Middle Passage and the arrival of slaves in this country. And I envision envision the slave ship. Moored in Jamestown or somewhere else. Where people could go on the ship and see. The conditions under which. Slaves had been brought to this country and get some notion of the

inhumanity. The savagery if you will the lack of civility on the ships that we could witness. I would be able to be a moving experience. And a telling experience. And a. Truth revealing experience of I say so. And I hope that even if a slave ship is not more than Jamestown. Or even on the Rappahannock that there will be a very considerably. Large size vividly portray for a vivid they portrayed replica of a slave ship even in dry dock are inside a building where people can go on it. And see how they packed them in packed them in. And how they they could not do anything but lie down

Neal and how they were brought broad would be brought up on the deck. For air. And for sunshine of a short period of time. And how that wouldn't tell the whole story. But you would have factual information such as how many died on the slave ship or that slave ship how many had this kind of disease and that kind of disease. How they'd lived in in in squalor and filth. During the passage. And why as a result only the most the most physically fit individuals would survive. And how they had to throw. Those who couldn't survive overboard in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean and how all

so. Many slaves jumped to their death. If they had the chance. For they felt that they would be taken back home by the save you or they would have their rewards in heaven but they would be better they felt than going into an unknown future. In the new world that that can be a graphic and chilling and dramatic illustration of what the institution of slavery was as it was evolving. And I hope that the. That the slavery history museum will have that in some form as it presents the story to the American people. Well is so wrong with me when you say it that I have insisted that is exactly what we will have built to scale and we've been fortunate enough to have some people we've known of slave ships and have built some of them

quadrants like to scale. We will have that in the museum and I can tell you just going into that one quarter ship that I went into was enough to just not have to have anyone tell the story. Just being there to see that little cubicle space that little tiny space that people would sit and have to sit in for months at a time only to get that brief period of respite for some. And as you've described in most revealing when I was a consultant to Spielberg I'm honest and I thought of this and thought how he conceived it and appreciated what we're talking about now and how as a result of it. We have that period this you remember Einstein opened his fist. The people on the ship.

And. It. It gets your head gripped you. And as indeed it should.

And we should have something like that. Dr. Franklin let me tell you what a pleasure it is for me to be here to have this opportunity to converse with you about your career and to pick up where we left off not quite fifty years ago. Let me pick up on one or two things that you and the governor mentioned and that is international dimension. One of the things that we talked about in our planning symposium was how one might locate our enslavement in the United States within the context

of the global slave trade and slavery the feeling being that Americans as much as they need to know about slavery in this country need also to know that it was a worldwide global phenomenon. What are your thoughts about that. Every major power in the world in the 17th and 18th centuries. Was involved in the slave trade. Portugal France Spain England and when it got to be somebody the United States and other other countries of Europe by Holland and several other countries of Europe. And this was they were dispersing slaves wherever. And at whatever point they would decide. And.

One cannot go to any Latin American country in this country in South America without understanding that this was a global phenomenon I should never forget the first time I've visited Brazil and brekky that I realize that. That Salvador and by ear was a. Major. Site for the. Exportation of slaves from. West Africa to Brazil. And after all this is a Salvador over that time was the capital of Brazil. And and one sees the culture. Of Africa in Brazil as one can see it in. South Carolina and Louisiana and could see the survival all kinds of African cultures and what not only is there this

dissemination of culture of West African and other kinds of other parts of African culture. To the new world and to other parts of the world. But. But the economic aspects of it are so vivid and so powerful and so determining and one looks at the way in which the economies of these various parts of the world developed. They go the arms the. Food and other things were being dispelled the summit is not merely to the United States we sometimes think of us as the only customers of West Africa but other parts of the country. But other of the continent but. Other parts of the world which are waiting for produce and for people and for other things from

Africa and in the same way that Africa is waiting for produce goods from other parts of the world into Africa. I think we could say that. That in addition to the Silk Route which one associates with Asian commerce to Europe and to the New World there was the African economy that was powerful in the world trade and slaves were really a part of this global economic development. And this is what I think we need to remember that this machinery was was in place for facilitating the the human and other kinds of cargo. That was disseminated not Franklin. I was very happy to hear you mention this Silk Road which showed international trade

especially as it expanded across Asia. The U.N.'s goal has also supported a slave in which all the trade in slaves that gave it indeed a global dimension. Which leads me to another question for you and that is the extent to which we should emphasize in the United States slavery the involvement of East Africa as well as West Africa. Very often one tends to emphasize the West African dimension increasingly central Africa but we want to get to the Zanzibar Tanzania and those areas were also involved in this. What do you think. How can one show a balance here. Is that a significant dimension. Well I don't think there's any question but that we ought to show in every way we can that slavery was a global

enterprise and the presence of of the slave trade in East Africa can be clearly and graphically illustrated and demonstrated and discussed and proved. I remember so well with. When I was in Zanzibar for example in 1963. The thing that impressed me as much as anything else was. Was the was the way in which the Zanzibar Koreans themselves understood and appreciated the fact that they had been connected with. This the slave trade is the same group as you call it from east to west. And the same thing is true and what was in it. Now in here when the people at Dar es Salaam that I talked with

were very anxious to know if the if the East African slave trade. And the East African slavery traditions. Were were known and understood appreciated and in the United States I told them that not as much as. As West Africa not so much as they deserve to be. And they were very much interested in and anxious to be a part of. The global economic and social development not that they boasted the institution of slavery or about this state but that they recognized the the way in which these things were connected. And affected them and in turn how they affected the developments of the world. So that all of these tend to underscore the significance of the global aspects. Of the slave trade. It's a

world it's a world of development and there's no denying that it was. I know that you have had considerable experience in and out of Goehring. Yes I can remember when I first went I think your son was there and showed me around gouré what kind of impact that gouré have on you when you first saw him. I'm not very sentimental and therefore I did not weep because I've seen people weep gouré African-Americans particularly but I was struck with the with the slave house. And the point of no return as you look down that long corridor and I can appreciate the fact that when slaves left although they might not have known what would happen to them. We now know what did happen to them. And it was if they were they were marching into

a new experience that would that would affect them the remainder of their lives. Some did not survive the Middle Passage. Others did but. You can't help but appreciate and understand it even be somewhat distressed by. What you know is going to happen to them once they leave Gori so that the experience there is telling one a troubling one and one that ought to be understood and appreciated particularly in the new world and particularly at the National Slavery Museum. For those who did not see the piece with you and Desmond Tutu. Can you tell us a little bit about that experience. Well. When we made this film on Goree Island in 2000 I think we.

Very much appreciated understood what we were about. That is what. What's the significance of this venture was and what we were trying to do was not merely talk. Talking about and learning to appreciate and try to. Try to communicate that appreciation to others what it meant to move from Goree Island to the new world. Slate How sounds are still there. Some were children some for women the worst for me. Most were in four months. Their bodies branded with the marks of their own age. Those who rebelled were punished. Eventually. All of them were said to pass through the so-called door of

no return. The door to his ship that would take them to a lifetime of slavery. We prayed for those who wait here. For those who cause them to be here. For the anguish and the pain the suffering. We were also trying to. Show. How and in. A little place like gouré you have. The struggle of slavery the memory of slavery. And then the healing process. Which would hopefully leave the people of gouré. Somewhat. Healthy in their outlook on life. Even though they have been through the Holocaust of the slave trade.

And I did appreciate that in a way that I hadn't hadn't before that is that you have here. Just a little just a little a little hour off the coast of Senegal. A little island that I've been through all this and experienced it all and yet. Continue to live and continue to to to thrive on the basis of it's appreciating its memory appreciating what it had been. And in that sense. That Laila communicated to us what it meant to be in slavery what it meant to get over that and move on to a new kind of life as they were living get underway. And as we said and ought to be living in this country what kind of attitude

do you want people to exit the museum with. And we talked about the the the feeling of healing the coming together of the people. Of all Americans and foreigners from whether coming through this experience of enslavement and seeing the horrors in as graphic a form as one can present them honestly. But at the same time accepting and saying that after all this was a human story and people overcame that story. I hope that the same museum. Will do just that. And I envy. The slave ship might do what but go reality did at some point you see. You have to you have to separate yourself from the experience that you just had going through the museum or going through the same house and go away. But at the point of exit

we need to have some reflection about what it meant. To go through this experience. And what what what the process of healing from that experience can do and making you a healthy. Person A person with a healthy attitude and outlook. And. That that will take some doing but we certainly have the materials to do it. And I hope that the museum will confront this and and be an institution that has the qualities of healing. I wouldn't want to end this conversation without having you comment on the book that is virtually synonymous with your name from slavery to freedom. I don't know how many editions that's gone through eight eight editions. And it remains the authoritative account of African-American History and

Culture. I wonder as you look back on can you give us some sense of the kind of impact that you've seen it have in terms of its influence on teaching its influence on research and indeed the way Americans tend increasingly to see themselves. Well that's a big order Joe. I don't know that I can fill it. First let me say that. I wrote from slavery to freedom here in Durham North Carolina and at the Library of Congress in Washington in 1947. And. I was in a small apartment here. With no facilities at all. Three room apartment. We didn't even have a desk. I was teaching the college with had no

offices for teachers whatever and no carols of of library or whatever. And there was no way to work. My wife said that you can't finish this book writing it in your lap. Which I was doing. And. This is 50 or for laptops. But I had I had a laugh and I was trying to write it and she said you can't do it. And she insisted I go to. Washington where she would send me money every week whenever I needed it and I broke the back of it. There came back here and finish it. I did not know what I was doing in terms of what it would mean to the larger world. I've just. I just wrote a book against my wishes because I didn't I didn't want to do it at that time. I had hoped to write a book on the subject at some point but not then.

But I was persuaded by my publishers to do it. So I wrote it. There were those who felt that it would not have any influence. There were those who felt that it would incur the wrath. Of Dr. Carter Woodson who had written the authoritative book up to that point. And there were those who felt it was much too young to do any of this. I was 31 but they were wrong on all counts. The first place. Dr. Woodson was one of the first people to congratulate me and wish me well. And to encourage me in every way possible. When he learned that I did. Secondly the. The impact on me. Was such that I. Modestly felt that I had made some contribution but not not not a world shaking action. Thirdly

as I as I began to see what was happening in terms of. Use. Of the book by so many people. I then began to feel that perhaps my efforts had not been in vain and that I had made some contribution. I continue to be. Surprised if not amazed. At what people say about about. I will never forget that when I retired as chair of the Department of History at the University of Chicago my successor in that office Imedi evilest. Said that I had created a field that's pretty big order. I had denied that until up to now. But maybe it was because he was evil was that he didn't understand what was going on but I appreciated it nevertheless. There was a judgment

that had been made but it has made a great impact on African-American studies whether in the area of study I suppose. Maybe so but I didn't feel it. And I really feel I'm I try to contribute to the field that was already in existence from my point of view. I had written a piece. Some years before when I was in my middle 20s. On. A course in the Negro negro colleges. And I had research that it was that there was a feeling already. You see. And I read that paper and meant to say women. Nineteen. Forty four five something like that. And I felt that there was a field and therefore when I was writing I was contributing in that field I wasn't creating a feeling making you know I was training to try and have some kind of impact on the way in which it was evolving.

And I accept that as a valid appraisal that I was trying to build the field would contribute to the field but not trained. Now the book is. 55 years old. It's run through eight editions. It is. I don't know how many printings within each edition. And it's sold three or four million copies. And from that point of view I suppose that. If you multiply that by two or three or four it has had some impact as some people have you know 10 or 12 million people have taken it seriously enough to read it. And from that point of view I suppose it has affected the way in which we view this feel. But as I was saying earlier. It's not just African-Americans that need to know about it. It's the entire

country. And and I feel that it's important. That whites Spaniards whatever I need to know as much about this feel as any of us. Who happen to be African-American. Otherwise there will not be the acceptance and. Tolerance of. Recognition. Of African-Americans as Americans. And that to me is a terribly terribly bored. Two things I would want the audience to think that they own the book because you published more than a dozen books. I don't know how many. The other thing I'd like to confirm with you would also has been published and translated into other languages translated and published in other languages. But of those nine it's been translated into. German Japanese French

Portuguese Chinese a remarkable contribution a global contribution. Let me ask you another question though somewhat shifting. There's a recent book by April 5th a team on a ranking of rage and I found it a remarkable book. You have a piece in there. Yes. I wonder if you could comment on the Howard University community of scholars at that time you were there at a time when such luminaries as Franklin Frazier right from the open and a long and I'm sure others tend to talk about that intellectual community and the extent to which it had any impact on your thinking and your subsequent development. Well yes you mentioned some others like Trabi Drew and.

And. Sterling Brown and. Others. Well they were all older than I was considerably older. I was a young upstart. I went to Howard and I was a full professor when I was 32 years old. And these men in their 40s 50s and on up. And I admired them we just looked at them and said oh this is really something. I was amazed the other day when. I read that bunch is Centennial is coming up next year. Oh my goodness. I couldn't imagine. They were all an inspiration for they were regarded as what we call vulgar fashion around in college around the university Super-Duper professors when they were up there. They were they were on the way up in the stratosphere somewhere

and we were just moving up and some of us were and we owe it by them. They were. They were men who were all in one way or another. Restless unhappy. And. It was it was not that they were Howard. It was that they couldn't go anywhere else. There was nothing they could do. They could rewrite the Encyclopedia Britannica because they that's very nice but you can't go you can't you can't go anywhere on having written it because we don't want you we can't use you. And this had the effect of pushing back on them and making them. Happy and rather rather bitter.

They took pride in Howard but they sat there and looked over at George Washington there where the big controversy is whether blacks could even go into the auditorium. And this this just did something to them. Whether blacks across the campus and the rest of Maryland College Park. But you broke out of that. Yes. I broke out of it but I was on only by accident. It was two things maybe. Maybe the acts of the circumstances at Brooklyn College where I went. And my age I never forget that perhaps I was regarded as one who was malleable. One that could make the adjustment. And one that perhaps would not be too much trouble and yet do my job.

So I went. But what means what what you need to remember is that. This is the end of a long period of trial which I had had at institutions which had no I think had no intention ever of employing me. That was Harvard. Wisconsin Cornell University of California at Berkeley where I taught we are approaching the 50th anniversary of Brown versus Board of Education by act of Congress. That commission has been established to coordinate commemorative activities across the country. President swaggerer to remember that commission and the first meeting will occur next month on the campus. Now going to people know

the extent to which others were involved. We normally think of Thurgood Marshall as indeed we should. But a lot of work went into that. A lot of research across disciplines. You know something about that. Can you speak to that briefly please. Well I was I was teaching in the summer of in the summer of nineteen. Fifty. Three. I was teaching at Cornell University one summer school students when I got a call from Thurgood Marshall asking me what I was going to be doing in the fall. I said I'm going back to our university. He said Well you know what else you're going to be doing. I said No what you say you're going to be working for me and you're going to be working on this Dargo aspects of this case. I did not. I was not aware of that and I had followed it to the extent of realizing that the the that the Supreme Court had handed down what might be regarded as a as a

temporary order. Namely that the court would reconvene in October and listen to. Answers to questions which had propounded at that time in the spring of 1953. Questions having to do with the intent of the framers of the 13th Amendment the intent of the framers of the Constitution and so forth regarding segregation and segregation in the schools. And he wanted me and a group of other historians and political scientists to study the primary sources of that period to see the extent to which we could argue that it was their intent or not the intent of the framers of the Constitution or the 13th Amendment 14th Amendment to outlaw segregation in the schools. And so I had I agreed to do it. He told me I couldn't disagree I couldn't refuse to do it. So I agreed to do it and I spent

much of the fall of 1953 in New York. I would teach my courses on the first three days of the week. And go to your last three days of the week and come back on Sunday to Washington to teach the following three days. And. There were others Rayford Logan as well. One of the people working in Alfred Taylor from Michigan was one of the people working for him from Wayne your in Troy. And Van Woodward from Yale and various other people. And we were all trying to answer these questions. Was Ken Clarke Kenneth Clarke was part not part of the. History historians but he was part of an army or research team and he was the one who we were jealous of him later. He was only mentioned by. The chief justice in his opinion and it was about the dogs that

had been used to illustrate the impact. Of. Whites and Blacks and education. And whatever it was I don't I don't. Looking back I'm not sure we had much effect. I think that too. I think that the the court came around position that they had to hand down this decision. And they were looking for ways and excuses to do it. And we hope that we would provide them with one excuse. Namely that we found something that was worth there could nail it down in a document. I'm not sure we did. There was a comparable mood among scholars and legal specialists today for reparations. And I read I can't remember the title. It was the Duke paper where you responded to a comment by a journalist. On reparations saying that blacks should not just forget the whole

thing. And I wonder if you would give us your comment on reparations and the possibility of scholars collaborating to provide the documentation necessary to prove the issue. Well it was a speech made by a chap named David Horowitz Horwitz here and I didn't hear the speech. I mean I've read the report of it I answered him. He said that we didn't. We were not entitled to anything and words to that effect. And. I simply argued that we were. That despite the fact that I was not optimistic about it. That blacks were entitled to infinitely more than anyone was willing to give them credit for. After all they helped to build this country free of charge. Help the bill get the United States capitol free of charge. They did all kinds of other things without

any kind of reintegration. And where would we be if they hadn't. Fell the trees and cultivate the land and build the buildings and so forth so that you can't save it offhand and. Out of out of hand that type of thing. I mean I said that. This country wasn't generous enough. I wasn't civil enough to admit that these things were owed us. If history is painful. John Hope Franklin reminds us that it can also be promising. He is certainly a man with a passion for scholarship and a commitment to sharing it. I'm

Patrick Swygert. Please join me next time at Howard. Do. You. Can. Do

- Series

- At Howard

- Episode Number

- 109

- Episode

- John Hope Franklin

- Contributing Organization

- WHUT (Washington, District of Columbia)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip/293-vx05x26017

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip/293-vx05x26017).

- Description

- Episode Description

- Historian John Hope Franklin discusses African American history, most centrally on slavery and our understanding of it today. He ends his interview with memory of institutionalized racism, his push against it, including his involvement in the Brown v. Board of Education case of 1954.

- Created Date

- 2002-00-00

- Asset type

- Episode

- Genres

- Interview

- Rights

- WHUT owns rightsWHUT does not have any rights documentation for the material.

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:58:55

- Credits

-

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

WHUT-TV (Howard University Television)

Identifier: (unknown)

Format: Betacam: SP

Duration: 0:58:30

-

WHUT-TV (Howard University Television)

Identifier: HUT00000043001 (WHUT)

Format: video/quicktime

Duration: 0:58:30

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “At Howard; 109; John Hope Franklin,” 2002-00-00, WHUT, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed January 16, 2026, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-293-vx05x26017.

- MLA: “At Howard; 109; John Hope Franklin.” 2002-00-00. WHUT, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. January 16, 2026. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-293-vx05x26017>.

- APA: At Howard; 109; John Hope Franklin. Boston, MA: WHUT, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-293-vx05x26017