The American Mind; 7; The Cast Iron Southerner

- Transcript

Alright. . .

. . W-Y-E-S-T-V and Tulane University presents. The American Line, a series of programs concerned with the intellectual history of the American Republic. Conducting the series is Dr. Robert C. Whitimore, Associate Professor of Philosophy at Tulane University. Program number seven, the cast iron southerner. . States rights.

Of all the slogans that have stirred the American mind, none has had further reaching consequences than this. It has divided north from south. We fought a civil war to settle the issue, and we settled nothing. From the time of Jefferson down to the present, states rights has been debated up and down the land. And it is the perennial tragedy of American politics that on no issue have so many spoken with so much passion about an issue they so little understood. For make no mistake about it. States rights is not a simple problem. It has infinite ramifications, and it goes straight to the heart of any man's political philosophy. In our intellectual history, no one has realized this more clearly than the man who did so much to pose the issue and to call his fellow Americans to account concerning it. South Carolina's John Calhoun.

Harriet Martino, the English critic, called him the cast iron man, and cast iron he was. He was born of pioneer stock on the western frontier of South Carolina in 1782. He grew up on a farm. He worked as a farmhand in the fields with the Negro slave. So he knew what it was to use his hands. His family prospered somewhat. And when he was a young man, it was decided that he was going into the law. And so he began to go to school to Moses Waddell's school at first in South Carolina. And then up to Yale College, far out of the orbit of ordinary South Carolinians. From Yale where he spent two years, he went to law school at Lichfield, Connecticut. And then back South again to Carolina, to the practice of law.

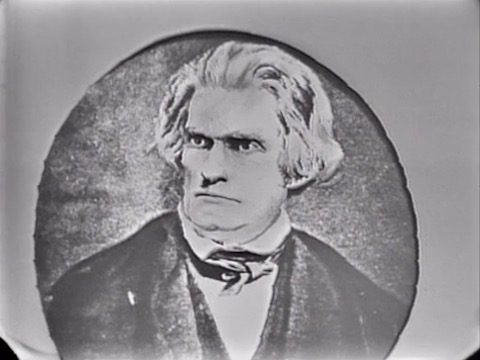

He didn't really like the law very much. That is, he didn't really like the tedium of it, the legalistic maneuverings of it. He apparently enjoyed being on circuit. And he apparently was a man who could carry his convictions to the people. Because we find him next in the South Carolina legislature. And then in the year 1810, when he was about 28 years old, he is elected to the Congress of the United States. And for the remainder of his life, some 40 years, he is in Washington in various capacities. This is what he looked like at the time he was elected to Congress. A handsome young man, very little there of the fiery, broody, tragic figure that we are going to see later on. Shortly after he became a congressman, he made the acquaintance of Florene Bonneau. Made the acquaintance, is perhaps too much of a phrase, because he had known the family. They were distant relatives.

In any case, the Bonneau's were Charleston aristocracy, and this up-country farmer really had no business with Charleston aristocracy, but he wooed Florene and he married it. And after they were married, he took her to the new plantation he had bought himself befitting a congressman. This is Fort Hill, where Calhoun was to spend some of the happiest moments of his life. The drawing of it really doesn't show too much of what the place was like. We have rather extensive descriptions of it, but he would always go back to Fort Hill whenever things got tough in Washington. From being a congressman, he became in 1816 Secretary of War in Monroe's Cabinet, and he revitalized the U.S. Army. The Army was in pretty sad shape when Calhoun took over the portfolio of the Secretary of War. It was in very good shape when he gave it up some four years later. His next step upward was to the vice presidency of the United States, and he is one of the most distinguished vice presidents the United States has had in the administration of John Quincy Adams.

Thereafter, it was into the Senate of the United States, and for the rest of his life, some 20 years, he was the leader of the Southern faction in the Senate, and there were some of his greatest moments played out, and there were most of the ideas expressed, which we're going to talk about this evening. There is one thing I think that really sums up John C. Calhoun's basic attitude better than anything I might say. In the year 1830, when Calhoun was already gaining a reputation as the leader of the Southern faction in Congress, there was a dinner held for the Democratic Party. Calhoun was hopeful of getting the Democratic Party to support his own version of state's rights and to support his anti-tariff proposals. The President of the United States, Andy Jackson, showed up, and everybody thought Andy is a good Southern who would go along and the Democratic Party would be committed to state's rights.

He came time for the toasts, and Andy Jackson, who was a patriot and who, as President, felt that perhaps he was beyond the range of sectional interest, surprised everybody by getting up and saying, the Union, it must be preserved. He was a shock to a man who had not seen the Union quite in that way, but Calhoun was equal to the occasion. He arose and answered Jackson's toast. The Union, next to our liberties, most dear. There you have the basic difference. One man saying that the liberty of the individual, the liberty of the minority, is what this country should stand for, what the Constitution of the United States guarantees. The other man saying, no, the Union, it may be right, it may be wrong with the Union, and we cannot allow anything to dissolve or to hurt the Union.

Individual rights then versus the national government. This is the basic issue that we know as states' rights. And as I said, it goes back to the time of Thomas Jefferson, because it is in Thomas Jefferson that you first have the issue of states' rights posed. And it's right there in the Declaration of Independence. We hold that men have certain inalienable rights. And you will notice that these rights, as they are spoken of in the Declaration, life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, come before any rights or duties under any form of government. These are inalienable. Authorization of the Kentucky and Virginia resolutions, late in his life. Jefferson very clearly spelled out his concern against a strong federal government. This is what is known as the strict interpretation of the Constitution. The Constitution says that any rights not expressly delegated to the federal government are reserved to the states.

And if this is taken in a strict sense, this means that the states have virtually sovereign power over everything that concerns the rights and obligations of the individuals within those states. This is spelled out more specifically by the great disciple of Jefferson, a man named John Taylor of Caroline. John Taylor believed that the government, as accepted in the Constitution, was not so much a federal government but a compact of states. Each of these states is sovereign. Each of these states in entering into the compact reserves unto itself, various rights which the government cannot and must not aggregate. Each of these states in voluntarily entering into this Constitution does not surrender these rights. In short, the rights of property, the rights of the individual, the right to a southern way of life, if you will.

These are paramount and no federal or national government as the Constitution sees it. And as Taylor reads the Constitution, must be allowed to interfere. When this gets expressed in Calhoun's language, it becomes somewhat more specific because John C. Calhoun really distinguishes three types of government. And these, he says, are what the founding fathers had in mind when they set up the Constitution. The first of these is what he calls confederation. That is to say a compact made by ambassadors of sovereign states, dissolvable at will. This was the sort of government that we had originally before our Constitution, a confederation governed by articles of confederation. Each of the states being sovereign, each of the states therefore being able to pull out at will, dissolvable at will. And that is the important thing.

Now, at an opposite pole from this very loose idea of confederation, which of course was very early in our history found totally inadequate as a means of safeguarding the interests of the United States of America. At an opposite pole to confederation is what Calhoun would call national government. National government, as Calhoun defines it, is one in which a single state in which each local unit is subject to the central agency. The state therefore in a national government is a state in name only. For John C. Calhoun, the very word state implies sovereignty. And therefore, if you take away the sovereignty of the state as you do under a national government where the central agency of the government says what's what. And the state is just a political or geographical entity which follows along. There is no sovereignty.

This is the sort of thing that the federalists were interested in. Our government as the federalist saw it was a compound of national and federal governments. But they wish to see it national. Why? Because only a strong central national government as they saw it can survive. Ben Franklin sums it up. Either we hang together or we all hang separately. And there is no middle ground. And indeed, the trouble with the US Constitution is that the men who made it were oscillating between the rights of individuals and the need to secure the safety of the new United States by a strong national government. And so they left a situation which ever since has been open to debate. The third type of government that Calhoun distinguishes is what he calls federal union. Federal union means separate sovereign states united through a central agency.

Now, federal union as Calhoun sees it is what we actually have laid down in the Constitution. Federal in that the states are sovereign union in that they are all gathered into a central agency with certain specific powers reserved to it. But the states are sovereign and that is the key to the issue. This is the way Calhoun sums it up in one of his speeches. Hours is a union not of individuals united by what is called a social compact for that would make it a nation. Nor of governments for that would have formed a Confederacy like the one superseded by the present Constitution. But a union of states founded on a written positive compact forming a federal republic with the same equality of rights among the states composing the union as among the citizens composing the states themselves. Instead of a nation we are in reality an assemblage of nations or peoples united in their sovereign character immediately and directly by their own act.

But without losing their separate and independent existence and that of course is the key without losing their separate and independent existence. And this theory of the state this theory of the United States as not being a confederation not being a national government but being a federal union so defined leads Calhoun to the elaboration of what he considers to be the essential states. The essential safeguards to the rights under a federal union the most important of these and the great issue of Calhoun's congress days was called nullification. Now nullification is a rather difficult thing what it boils down to technically is this it is the legal repudiation of a federal statute. In Calhoun's day it worked sort of like this the issue was the tariff in 1828 the North wanted it they wanted protection of their industries the South didn't wanted it was disastrous for the cotton makers.

And so therefore how do you deal with such a situation well if each state is sovereign and each state reserves to itself the right to take into its own hands powers not expressly delegated to the federal government then each state has the right to nullify any laws which are inimical to its best interest. For instance what they did in Carolina was to call a constitutional convention and they passed a statute of nullification which simply says we declare null and void this specific law. Well how do you get around this sort of thing Calhoun felt that if a state was to do this sort of thing the next step was to call a amendment convention so that you could present the issue to all the states and perhaps amend the Constitution deal with it. Of course in practice this didn't happen.

And when you had nullification when one state said we simply do not acknowledge this federal law what is the government to do? Well in this specific instance what President Jackson did was to ram what he called the force bill through Congress which said in effect you obey that law or we send troops and we will enforce the law. Well when you get to that sort of a situation when saying we won't obey the other saying you must you come down to the second alternative which was to play such a tremendously important part and lead to the civil war. This is when nullification becomes secession that is to say withdrawal from an association of partners. Now the question is under what rights do states nullify or secede and the answer that Calhoun gives is very simple. If we are a federal union and if a federal union is composed of sovereign states and a sovereign state must be the judge of its own internal order and its own internal law then we have as Calhoun put it an assemblage of nations and that being so they cannot surrender their prerogative to nullify.

They cannot surrender their prerogative to secede. Now Calhoun really didn't think that it ought to come to secession. Nullification is not secession it's sometimes confused with it. Calhoun simply saw nullification as a means whereby a state which was hurt by some law could express its disapproval and start the constitutional amendment process to bring about an equity in the matter. But of course it didn't work out this way and so he next proposes what he calls the theory of the con current majority because of course you may say well after all shouldn't the majority rule in these matters. Well Calhoun asks what do you mean by a majority? There are two different modes in which the sense of the community may be taken.

One simply by the right of suffrage unated. The other by the right through a proper organism each collects the sense of the majority. But one regards numbers only and considers the whole community as a unit having but one common interest throughout while the other regards interests as well as numbers considering the community as made up of different and conflicting interests. So you should then be governed by the majority but it should be a con current majority. For instance suppose we are in dispute as to whether or not the federal government has a right to interfere with pupil placement in schools, one of the big issues we have before us today. All right you take a poll of the various interests in the community, the white interest, the Negro interest, the mercantil interest, the business interest, the property owners. Now the con current majority is the majority of the majorities within those interests. Suppose you have three whites and three Negroes and two of the whites vote for one thing and one of the Negroes votes for another thing.

In short you have two absolute majorities opposed. You can do nothing you see, you're at a stalemate. In short the idea of the con current majority is that you can never really say that anything ought to be done or ought to be imposed upon any state or region unless the various interests from all parts of the affair have given a majority approval. So therefore if the south as a minority is always overruled by the west and the north this is not fair because this does not take into account Calhoun argues the con current majority. We shouldn't just lump all the north and the west together is against the south. We should take the various specific interests in each region, poll them, see if there is a majority in each case and if there is then perhaps we can see whether we'll abide by the rule. Of course if we say we can't abide by the rule then we go back to nullification and secession.

Now this may all sound rather revolutionary and you say well after all doesn't the declaration and doesn't the constitution really say that all men are created equal. They are endowed with certain inalienable rights. No, no says John C. Calhoun they are not and this raises the fundamental issue because of course behind all this talk of secession and nullification was the slavery question. The south was slowly being strangled by it. It was an essential to their economic well-being. It was anathema to the north. And of course the northern would always throw in their face all men are created equal. So therefore how does one meet such an objection? Well this is what John C. Calhoun says. Taking the proposition literally it is in that sense that it is understood. There is not a word of truth in it.

It begins with all men are born which is utterly untrue. Men are not born. Infants are born. They grow to be men. And concludes with asserting that they are born free and equal which is not less false. They are not born free. While infants they are incapable of freedom being destitute alike of the capacity of thinking and acting without which there can be no freedom. Besides they are necessarily born subject to their parents. And remains so among all people savage and civilized until the development of their intellect and physical capacity enables them to take care of themselves. They grow to all the freedom of which the condition in which they were born permits by growing to be men. Nor is it less false that they are born equal. They are not so in any sense in which it can be so regarded. And thus as I have asserted there is not a word of truth in the whole proposition as expressed and generally understood. Now this too has a sound philosophical background because the philosophical basis of such statements is the Aristotelian doctrine that some men are naturally slaves and some men are naturally free.

And of course there is a division in capacities among men. And this being so we must say that those lines of the declaration which assert that all men are born free and equal and entitled to certain rights cannot be held in all literalness true. These are pernicious words. These are words which in Calhoun's eyes can only lead to the tyranny of the numerical majority and must end in the crushing of the South. And if that is so then the South has no alternative to revolt. The South has no alternative but to assert its liberty. This is what Calhoun has to say about this liberty. Liberty indeed though among the greatest of blessings is not so great as that of protection in as much as the end of the former is the progress and improvement of the latter. While that of the latter is preservation and perpetuation and hence when the two come into conflict liberty must stand ever ought to yield to protection as the existence of the race is of greater moment than its improvement.

It follows from what has been stated that it is a great and dangerous era to suppose that all people are equally entitled to liberty. It is a reward to be earned not a blessing to be gratuitously lablished on all alike. Well I could go on reading from Calhoun but I think you get the general drift as America went on to the middle of the 19th century. And these issues the rights of individuals to assert their own way of life became more and more pressing. The issues were raised again and again as America expanded westward. For instance when Americans began to think of taking over the Mexican territories of buying them from Mexico or having Mexico seed them through a treaty of annexation. And the question arises shall these states be slave or free and we have such a thing as the Wilmot proviso which says that there shall be no slavery in any territory acquired from Mexico.

We have the same sort of thing coming into being with the question of the admission of California and Oregon to the Union. What does it all add up to? It adds up to the fact that these states come into the Union free and thus the Union is overbalanced. The majority oppresses the minority and the minorities only recourse is to secession. Well you may or you may not agree with that but in any case I think you owe it to yourself to make yourself acquainted with the arguments. The greatest of the southern philosophers puts them to you. You can find these arguments in a book called Calhoun basic documents which is what I have been reading from tonight. For those of you that want to find out something more of the philosophical background in which these arguments become relevant and want to gain some knowledge of the issues in their broader context.

I recommend that you look at August O. Spain's John C. Calhoun. This is a well written little book. It's quite clear. There is another book that I would call your attention to. This is called the Cast Iron Man John C. Calhoun and the American democracy by Arthur Styron contains an excellent discussion of the basic political issues involved. And finally for those of you who would know something more about the man himself there is Margaret Coitz biography John C. Calhoun, American portrait. If you will take a look at these books you will come to a greater understanding of the issues involved. You may not agree because these issues are dynamite. Can America survive if we allow states rights to thrive? Is it the intention of the Constitution that the states should have these rights?

You all know as I do these issues are being debated today. Next week turning from states rights we shall consider individual rights and the problem of free thought in the young republic. Good night. The American Mind. A series of programs concerned with the intellectual history of the American Republic is conducted by Dr. Robert C. Wittermore, associate professor of philosophy at Tulane University. The American Mind is a studio presentation of WIES TV. This is National Educational Television. This is National Educational Television.

- Series

- The American Mind

- Episode Number

- 7

- Episode

- The Cast Iron Southerner

- Producing Organization

- WYES-TV (Television station : New Orleans, La.)

- Contributing Organization

- Library of Congress (Washington, District of Columbia)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip-512-6t0gt5g764

- NOLA Code

- AMND

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip-512-6t0gt5g764).

- Description

- Episode Description

- "Professor Whittemore here talks about the problem of government which grew in the South. In his discussion of three types of government - confederation, national government and federal union - Dr. Whittemore talks about John C. Calhoun and John Taylor. He discusses states' rights, nullification and secession." (Description adapted from documents in the NET Microfiche)

- Series Description

- The purpose of the series is to explain the background and development of American thought and philosophy. Starting with the Puritans, various philosophies and trends of thinking are traced to the mid-nineteenth century. Each episode is basically a lecture, in which Professor Robert C. Whittemore uses various groups and other visual aids. His lectures are planned for a general adult audience. Dr. Robert C. Whittemore, the acting head of the Department of Philosophy at Tulane University, has appeared on at least 138 educational television programs in the past three years. He has appeared on the History of Ideas, Great Religions, and The American Mind. He has also appeared on many panel shows. He is the author of fifteen articles, mostly on metaphysical and theological subject. Dr. Whittemore has also contributed approximately thirty articles to American People's Encyclopedia. A book reviewer, he is now working on two books himself. The Growth of the American Mind, a book based upon this TV series, will be published in the Fall 1961 and In God We Live, an analytic history of pantheism, will be published in the Fall 1962. Dr. Whittemore's educational specialists are philosophical theology, American philosophy, and comparative religion. He received his Ph.D. in philosophy from Yale University and was an instructor there for 1950 to 1952. The series was produced by WYES-TV, New Orleans, Louisiana. The 12 half-hour episodes that comprise the series were originally recorded on videotape. (Description adapted from documents in the NET Microfiche)

- Broadcast Date

- 1960

- Asset type

- Episode

- Topics

- Education

- History

- Philosophy

- History

- Philosophy

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:30:21.654

- Credits

-

-

Host: Whittemore, Robert C.

Producing Organization: WYES-TV (Television station : New Orleans, La.)

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

Library of Congress

Identifier: cpb-aacip-e46b62cec95 (Filename)

Format: 1 inch videotape: SMPTE Type C

Generation: Master

Duration: 0:29:00

-

Library of Congress

Identifier: cpb-aacip-11146448763 (Filename)

Format: 2 inch videotape

Generation: Master

Duration: 0:29:00

-

Library of Congress

Identifier: cpb-aacip-cdab30f05f9 (Filename)

Format: U-matic

Generation: Copy: Access

Duration: 0:29:00

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “The American Mind; 7; The Cast Iron Southerner,” 1960, Library of Congress, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed January 5, 2026, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-512-6t0gt5g764.

- MLA: “The American Mind; 7; The Cast Iron Southerner.” 1960. Library of Congress, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. January 5, 2026. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-512-6t0gt5g764>.

- APA: The American Mind; 7; The Cast Iron Southerner. Boston, MA: Library of Congress, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-512-6t0gt5g764