Main Street, Wyoming; 201; Trona Mining in Wyoming

- Transcript

This program made possible by a grant from U.S. Energy and Crested Butte Corporation, part of a family of companies in the mining and minerals business, providing jobs for Wyoming people since 1966. Welcome to Main Street Wyoming. Today our pop quiz is, what is Trona? Some of you may know that Trona is mined underground in the Green River area, and you may associate it with Soda Ash. You may even think it is Soda Ash. You may also know that it's a huge industry and actually generates something like 800 million in revenue in the state. It's really one of Wyoming's best kept secrets. Most of you don't know what Trona or Soda Ash is. So today I'm 1600 feet underground trying to look at it myself and tell you a little bit about it. Somewhere down here we can find a piece of it. Today we're going to meet

the people who mined it, who crushed it, and who processed it, this Trona into Soda Ash or sodium carbonate. So join us as we travel down a very different Main Street in Wyoming and meet the people who bring you things like laundry detergent, the scrubbers, the filter power plants, pollution ads, baking soda, what have you. It's all here. Come along. I'm talking to Jay Lyon, Public Affairs Manager for FMC Wyoming Corporation. Jay, when people in Wyoming think about mineral resources, they tend to think of coal or oil and gas,

but if I were to say to them, we produce more Trona than any other place in the world, their question would be, what is Trona? So why don't you tell me, what is Trona? You're right. Most people don't know and haven't ever heard much about Trona. But Trona is a naturally occurring mineral that's located here in southwestern Wyoming, one of the few deposits in the world. Okay, now we know that Trona is mineral and it's in deposits here in Wyoming. What do you do with it? We actually bring it out of the ground. We mined underground at about 1,600 feet and bring it out of the ground and refine it into soda ash. You got to go a little further than that. What do you do with soda ash? Soda ash is a major constituent in the manufacturer of glass. It's used in all kinds of manufacturing processes for metals and for plastics and detergents. It's got universal use. It's one of the most common chemicals known to man. Let's run through a few of those things. I've heard fire extinguishers. I've heard tide detergent. What are some other examples of where we use soda ash? About half of it goes into the manufacturer of one former glass or another and most of glass is made up of the container industry. However,

there's fiber glass and there's flat glass like auto windshields and things like that. And then there's specialty glass like light bulbs. So that covers a glass segment. There's a substantial amount goes into pharmaceuticals and other chemical kinds of compounds. It's an alkalized source for other chemicals and then it's used in a lot now in environmental controls and being able to clear the environmental of some of the more nauseous compounds. Another of the best kept secrets about the drone industry is that it's something of an economic success story. Why don't you tell us a little bit about the markets and the economics and how it all works? Well, because soda ash originally was made synthetically in the United States and throughout the world today it's mostly made synthetically. This is a natural deposit where we can convert an ore that is twice as hard as coal into the raw material soda ash and compete with those synthetic operations. Synthetic means that you can mix some chemicals together and you get soda. So we compete with that as a

matter of fact, there are no more synthetic plants in the United States. All soda ash that's used in the United States comes from the Green River base and 90 some percent of it. And so it's a basic raw material for the world that everyone needs. And a lot of Wyoming's China is now going overseas. That's right. Over the last 10 years or so the export market has grown considerably because we're able because of the economics of this developed reserve. We're able to compete with the synthetic producers throughout the world very effectively. You've been other conversations described soda ash as a mature industry. What do you mean by that? It's a commodity chemical which is like any other commodity in the world today. It's mature from the fact that it's been around since the beginning of time. So to ash, the word soda ash implied that it was made somehow by fire and it was. It used to be made by burning trees or seaweed or things like that. So it's been around since the Egyptians. Actually they were the ones that actually began using it as an embalming. Believe it or not, an embalming or an embalming mechanism.

And then they also make glass from it. And FMC Wyoming Corporation is one of the oldest trun operators in the state. In fact, it is the oldest, it may begin the development of these mines. Give us a little history of FMC and the other companies involved in it here. FMC was the first producer in the basin. And the actual discovery of the trono occurred in 1938. The first production of natural soda ash occurred in 1948, 10 years later by FMC by the way. And our business has been continually growing since then. And we are at a point now where we're diversifying and adding value to the soda ash that we make here at this site by making other products. What kind of diversification are we talking about? Plants in addition to the mine? That's right. We'll take the soda ash is made here and rather than sell it out of state or out of the country, we'll actually use that raw material to make other products like caustic soda. There are producers who are making sodium sulfate, which is another chemical.

It's made by carbonate, which is baking soda that we know very commonly. It's used as a rumen buffer or an alkycelser for cattle or dairy cattle. We've got other facilities that other companies in the basin are looking at, surely we're looking at. But I think the diversification is the key to the real success of our operations here. The industry still seems to be moving along great guns. Can you tell us a little bit about expansion plans and what to expect next from the drone industry here in Sweetwater County? As a matter of fact, there are some announced expansions and I think I could say that just about everybody in the basin is looking at expansions because if you look at what's happening in Eastern Europe and some of the third world countries, any country that is trying to develop has to have soda. Soda ash is absolutely essential for development of any country. I'm talking to Ken Bigler. He's superintendent of the number seven shaft of FMC's Tronomine here. Tell me how you started out.

Really, I started out when I was 18-year-old kid. I came down. I was just waiting to get drafted in the Army and I only needed a job for three months and that was in January of 1952. But I didn't get drafted at that point in time and when I did, I went in the Army and came back. So my three-month job lasted almost 40 years in January. I've had 40 years here at FMC. Did you start out as a minor underground? Yes, I started at the old number one shaft here. At that point in time, there were a total of seven production people went down on day shift in the mine and seven on swing shift and that was the height of the production that came out of the mine at that time. What was the work like then that you had obviously different sorts of machinery and different ways of doing things? Yes, there's been a lot of improvements. At that time, your first job in the mine was they had what you called a grizzly down there. It was a railroad square iron job that you

dumped the ore in and you broke the chunks and fit them through one square foot holes down through there. There weren't any crushers or anything at that point in time. So your job was breaking chunks all day long. Essentially, you were the crusher. So now we have big crushers and a lot of things. There's been a lot of improvements since those days. There was all together a different type of mining in those days. You know, you had, you blasted places. You had conventional crews now which they've done completely away with now and the miner crews, they've got miners down there. But most of it, they're going to the long wall and that, you know, and it's different type of mining altogether. With that, the company took me down into the mine to see just how different this type of mining is. Our guide was mine engineering supervisor Dave Hutchinson, who was outfitted with a diesel-powered Jeep and a picnic basket. We proceeded to drive through the seven

miles of underground maze that is FMC's Tronomine. And when I got to the mine face, I met some real honest-to-goodness Tronominers who talked about their chosen professions. How long have you been working here in the Tronomine? Well, this last time, about 13 years, and then I quit and was here a year before that come back. You do, have you worked in other mines? Yeah, I was a hard rocker in Uranium mine. Tell me a little bit about how the two jobs compare. Your old Uranium hard rock job in this one. It's a vacation place. Well, tell me what that means. Well, in a hard rock, you've got to be tough. Down here, you just got to be here. Do your job, and that's it. Is that simply because the rock, I mean, hard rock obviously implies harder rock, but what is the real difference in terms of the kind of work you have to do? Well, machines are air tools, what you got, and it's, you do a lot of picking shovel

and putting in timbers. It's about a four foot drift sometimes in a hard rock on an angle, you know, like this, hands and knees sort of thing. It's quite a bit different. It's not, it don't take so much physical work down here. It's a good place to retire at. Can you make any comparisons between the life of a coal miner and the life of the Tronominer? Well, I think the life of the Tronominer this day and age, it's improved so much over the coal mines, the conditions, and the other neat thing about it is, I think, that everybody loves it. It's much easier to wash off, too, but coal mining, I think, is a lot harder way to mine ore, and they have to contend with a lot more serious dust conditions, and we do in the Tronomines, and I think coal mining in general is underground coal mining and it's probably a lot harder than our underground Tronominer. My whole family, all my uncles

and grandfather and even my dad worked in the mine at one time, and before I come out here I worked about four months at a coal mine that stands very, just outside of rock strings there, but they closed down. I wasn't too happy about mining at that time. coal mining scared me, I wasn't comfortable down there at all. What's the difference? Well down here, it's more white open, the gussar bigger, and it isn't black all over the place, and coal spits at you, and I was young at that time, I was scared to hell out. Tell me what you mean by spits at you. As the roof takes pressure and that decides to spit at you, I mean it'll, you know, the pressure there, and it was just scary, it was scary. I just got out of the army, I was young yet, and that's the one thing I swore I'd never do is mining, because I grew up in a coal mining town, and I swore I wouldn't

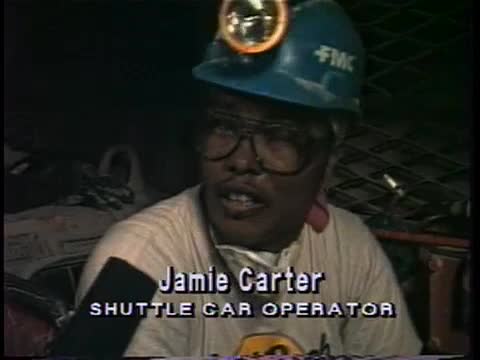

do it, but didn't have much choice. There was no other job to have, so I ended up doing that. You've got a daughter who's working in the mine now? Yes I do. Jamie, how did that all happen? Well, she put her application in, and they called her, and they told her she had to go into mine, and she said she didn't care, she just needed a job, so she went into mine, and she seems to really like it. It goes back the other way too, you had a father who worked in coal mines. Yes, my dad worked in the coal mines for like 24 years around, and then he finally got a job with the city, when the mines closed down, so we stuck around and he's still around, and I'm still around, and we got the carter's got their foundation in. Jamie, what's your job down here? I'm a shuttle car operator. You want to tell us a little bit about what a shuttle car does? Well, I haul the ore to the belt, or dump it on the belt, and I go back to the miner and get another load and dump it, so I do all day. And tell me a little bit about how that fits into the rest of the system. We've got

machines up ahead of you that are actually cutting the rock out. Yes they are, it's the miner. Today I'm in a bore miner, but usually I'm going to join a miner section. So they will do that and load that onto the back of this, and you'll take it out in the shuttle. Yes I will. And then where does it end out when you're done with it? After it goes to a couple belts, and then it goes into two shafts, where it dumps out, there's two main shafts, four shafts and two shafts. How long you've been doing this kind of work? Two and a half years going on three years. And what got you into it in the first place? My father. Now you've got a daughter in the mine, and you had a father in the mine. How about yourself? How come you're not down in the mine? I ain't going either. I don't know. I've been on here like I said 24 years, and I've never ever been in the mine. I don't want to go. No, my dad's scared of death. I'm telling you the truth. He's been out here almost 24 years, and he's never been down there, not once. So did you have any trepidation when you first came into the mine, any kind of fear? No, I wanted to come down. He didn't want

me to, but I did. You ever find you have somebody who wants to do the job, signs up, takes the training, and then can't handle it? Not very many, but we have had one or two. Quite a few years ago, we had a person that took the surface training, and then got ready to go underground for the last part of it, and stepped on the cage, and before it even went underground, the person just said, no, I can't make it. Take me back out. But that's very, very rare. It doesn't happen too often. How long you've been working in the mine? 12 and a half years now. Are you from around here originally? From Rock Springs, yes. I was born in Wheatland, and then I moved Rock Springs, and I've been there for about 36 years. When you're outside the mine, do the people that you hang out with and the people you're family and whatnot know pretty much what you do and understand what it is you do down here? Yes, because a long time ago, we made a movie, and it shows the different jobs that different people do, and I showed that to all my friends and relatives, and they get a good idea of what everything is down here. Do you have relatives who work in the

old coal mines or who work in the mine here? No, all my relatives was construction workers, highway construction. And how about you? Do you feel at home doing this? Is this something you can see doing through? Oh, this is home. I love it. Especially every payday. Our mine is so massive and large and, you know, encompasses so many square miles, and we have machines down there that weigh 100 tons and big cars and jeeps and stuff that run through the mine and transportation that's pretty nice. And so I think a lot of people have the wrong concept about mines that they're little small dog holes and nasty to work in, but I think if you were to talk to most of our miners here that they pretty well enjoy their work. What it would be that people would like more about being down in the mine than up on top? I think more less than peace and quiet than anything. Didn't seem too quiet to me rolling over here. Yeah, it is though. You know, you have

your own little space to work in, and that's it. Where up top, you always see people constantly. But down here, you just see who you're working with and that's that? In a given year, do you work all over the mine or do you tend to work in one area? We work in one area, but we have in different times worked all over, you know, when we drive around in these caverns, we tend to think we don't know where we are. It all looks the same. Is one area of the mine different from another? Well, you get familiar with it. You know, where you're going and how to get out, you know, when we go over to five shafts or something, we're a little turned around for a while. At least I am. Anybody ever gotten lost here? I probably not lost just misdirected for a few hours. But there's always signs telling you how to get out. There's been a few people who've gotten turned around. You gave us some advice earlier about what to do if you are turned around. Why don't you give it to me again? Okay. We've got markers on the ribs that say 9XC, which should be like nine crosscut. If you go

in descending order, eventually you wind up back at a fresh air shaft. The other thing is if you always keep the wind blowing in your face and then you wind up back at a fresh air shaft. It may take a couple hours of walking, but she'll get there. The best thing is when everything's running, then you get to kick back and relax. Take care of all the dead work, the tubing, make sure they have good ventilation in the face where they're cutting. And then if you get all that taken care of, then you could kick back and relax a little bit. You get to feel kind of affectionate for your machines here since you work with them so much. No, no, not at all. When they're running, that's when they're my babies. When they're broke down, I hate them. Since it's so dark, you know, we have different signals to use and you find yourself when you go up top, you're using those same signals to people and you're looking as like, I don't know what I'm doing. Well, give me an example. Well, when, say you want someone to come here, you flash your light like this around. So when you go up top, you know, you see somebody and you want to come here and you're going like this, you know.

That's what I'm trying to do. Yep. The people that you work with down here, do you stay with them or hang out with them up on the surface? Sometimes, usually, you know, they're just like your family. You spend enough time with them down the air. They're like, you do up top with your regular family. How do you feel about the team you work with here? Oh, they're pretty good. They seem to be a lot of long-term people who've worked here for quite a while. I think anybody's got any sense to stay put. You tend to be here until you retire. Yeah. Another six or eight years. Well, I think our people at mining is number one thing that FMC makes money off of. If you have good people and quality people in which we have a lot of them here at FMC, that's what makes you the money. Not the big brand new machine. If you don't have quality people and people that are interested in loading or for you, that big machine is next thing to worthless to you. If you have quality people, that's where the money should

be made. What would you say the value of teamwork is down in the mountains? Oh, that's essential down here because if you don't have teamwork, you know, if you don't trust your co-worker then you should be down here. I've enjoyed. It's been a major part of my life. My family's life, you know, it's been great. I what can else can I say? I also met Laura Lake, a college student performing work in the mine for the summer at near union wages. For families of plant and mine employees, this FMC program provides a number of benefits. Some of the advantages of the summer hire program are that you can make good money to continue your education. You can't make money like this anywhere else. Most jobs pay four dollars below union scale wages which are in the contract and there are even some salary positions that are pretty good. Another advantage is that you get to actually see where your parent works because until the past couple of years where they had the

picnic out here that even people are not allowed to come out here and see, so it's really interesting to see where my dad actually lives. Are there other young people spread out in the mine here doing what you're doing that you know on? This summer there aren't. There's one other girl in the mine. She works in the shop at HF, but there's a lot more on the surface. There's about 48 people on the surface this summer working and they do all kinds of jobs. Maintenance and there's a yard crew of course where they have to shovel and that stuff, but there's also good jobs like running equipment and like at mono power they have technicians and everything. You had your choice between working down here like you're doing and working on the surface which would you have chosen just for this summer? Well my job I work both places. I work six weeks on the surface this summer and I like working both places. I do the same thing in both places. It's interesting I get to meet a lot of people.

The mining is just the first step. After the Trona comes out of the ground a great many other things have to happen before it becomes soda ash. With us today is Ray Frint who will take us on a tour, a walking tour of FMC's processing, right? Thank you. Behind me you can see the first step in the Toronto processing and that is to hoist the ore to the surface. FMC has a Kepi friction mounted hoist which encompasses two large 23 ton skips. You heard one of those emptying. One of those comes to the surface every 90 seconds and drops 23 tons of ore into the surface processing equipment. At this point the ore is either screened so that the smaller particles can go directly into the soda ash processing and the larger parts of particles are sent out for stockpiling

on an ore spock pile so that the plant can continue to operate when the mining operation is shut down. We're now located in the calcining area of the plant. After the ore is hoisted it is then crushed to find particles and then these particles are fed into a large rotary calciner which we see here. We use natural gases a fuel. This eats the ore particles up and converts the trona into soda ash but the insoluble and other impurities are still with the soda ash so it is referred to as crude soda ash. The soda ash is inseparated from the products of combustion from the natural gas firing, goes through scrubbers, cyclones and then the gas is exited to the atmosphere. Following the calcination step which we previewed

the ore is then dissolved in a water solution. We're handling on approximately 7,000 tons a day of ore and this is dissolved after calcining into about 2,000 gallons per minute of a water solution. This then goes to a very large settling tank where the insoluble material is removed and allowed to settle out of the solution and is then pumped to waste. The solution is then filtered in very large filters to remove any other material that didn't settle out such as wood chips from the mine and other material that didn't sink. We have here the main control room for the soda ash surface processing. This is the area which monitors all of the temperatures, the flow rates, the pressures, the motors and determines everything which is happening in the plant. The ore is dissolved into hot water that is kept near

boiling to facilitate fast dissolving and the solution is kept as hot as possible so all lines, tanks are insulated and this means that we require less heat in the next step of the process which is to evaporate the water which was added. One half of the process is approximately 1,700 gallons per minute and all of this water must be evaporated before we reach the final product. The soda ash liquor is sent to large evaporators where water is boiled off from the solution and this forms a soda ash monohydrate meaning some water is in the crystal which is crystallized out of the solution. These crystals are then collected and go through a centrifuge where the liquor associated with them is sent back to the evaporators for further evaporation. Following the centrifuging the crystals at FMC are sent to a fluid bed

dryer which is the unit just behind me here. Air is withdrawn from the atmosphere, is heated, goes through a unit where heat is supplied via steam and as the soda ash crystals are tumbled in the unit they contact the hot pipes, finishes the drying process and we then end up with soda ash that is ready for sale. FMC ships approximately one train load of soda ash every day of the year. Soda ash may be as J. Lion says in mature commodity with no room for expansion in the markets but in fact the industry here in Wyoming is expanding rapidly. Mines are growing and enlarging the new processing plants are going in. Now at least we know what it is and you can keep your eye on it as you travel along Main Street, Wyoming. This program made possible by a grant from U.S. Energy and Crested Butte Corporation,

part of a family of companies in the mining and minerals business providing jobs for Wyoming people since 1966.

- Series

- Main Street, Wyoming

- Episode Number

- 201

- Episode

- Trona Mining in Wyoming

- Contributing Organization

- Wyoming PBS (Riverton, Wyoming)

- AAPB ID

- cpb-aacip/260-203xsmk7

If you have more information about this item than what is given here, or if you have concerns about this record, we want to know! Contact us, indicating the AAPB ID (cpb-aacip/260-203xsmk7).

- Description

- Episode Description

- This episode follows Geoff O'Gara as he interviews experts working in the trona mining industry in the state of Wyoming. The main focus of these interviews is the process by which trona is turned into soda ash, or sodium carbonate, a chemical substance found in everything from glass to detergent to baking soda.

- Series Description

- "Main Street, Wyoming is a documentary series exploring aspects of Wyoming's local history and culture."

- Copyright Date

- 1991-00-00

- Asset type

- Episode

- Genres

- Documentary

- Topics

- History

- Business

- Local Communities

- Rights

- Main Street, Wyoming is a public affairs presentation of Wyoming Public Television 1991

- Media type

- Moving Image

- Duration

- 00:27:50

- Credits

-

-

Interviewer: O'Gara, Geoff

- AAPB Contributor Holdings

-

Wyoming PBS (KCWC)

Identifier: 30-00945 (WYO PBS)

Format: U-matic

Generation: Original

Duration: 00:30:00?

If you have a copy of this asset and would like us to add it to our catalog, please contact us.

- Citations

- Chicago: “Main Street, Wyoming; 201; Trona Mining in Wyoming,” 1991-00-00, Wyoming PBS, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed January 29, 2026, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-260-203xsmk7.

- MLA: “Main Street, Wyoming; 201; Trona Mining in Wyoming.” 1991-00-00. Wyoming PBS, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Web. January 29, 2026. <http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-260-203xsmk7>.

- APA: Main Street, Wyoming; 201; Trona Mining in Wyoming. Boston, MA: Wyoming PBS, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-260-203xsmk7